Knutz, P.C., Jennings, A.E., Childress, L.B., and the Expedition 400 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 400

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.400.102.2025

Expedition 400 methods1

![]() P.C. Knutz,

P.C. Knutz,

![]() A.E. Jennings,

A.E. Jennings,

![]() L.B. Childress,

L.B. Childress,

![]() R. Bryant,

R. Bryant,

![]() S.K. Cargill,

S.K. Cargill,

![]() H.K. Coxall,

H.K. Coxall,

![]() T.D. Frank,

T.D. Frank,

![]() G.R. Grant,

G.R. Grant,

![]() R.E. Gray,

R.E. Gray,

![]() L. Ives,

L. Ives,

![]() V. Kumar,

V. Kumar,

![]() S. Le Houedec,

S. Le Houedec,

![]() J. Martens,

J. Martens,

![]() F. Naim,

F. Naim,

![]() M. Nelissen,

M. Nelissen,

![]() V. Özen,

V. Özen,

![]() S. Passchier,

S. Passchier,

![]() L.F. Pérez,

L.F. Pérez,

![]() J. Ren,

J. Ren,

![]() B.W. Romans,

B.W. Romans,

![]() O. Seki,

O. Seki,

![]() P. Staudigel,

P. Staudigel,

![]() L. Tauxe,

L. Tauxe,

![]() E.J. Tibbett,

E.J. Tibbett,

![]() Y. Yokoyama,

Y. Yokoyama,

![]() Y. Zhang, and

Y. Zhang, and

![]() H. Zimmermann2

H. Zimmermann2

1 Knutz, P.C., Jennings, A.E., Childress, L.B., Bryant, R., Cargill, S.K., Coxall, H.K., Frank, T.D., Grant, G.R., Gray, R.E., Ives, L., Kumar, V., Le Houedec, S., Martens, J., Naim, F., Nelissen, M., Özen, V., Passchier, S., Pérez, L.F., Ren, J., Romans, B.W., Seki, O., Staudigel, P., Tauxe, L., Tibbett, E.J., Yokoyama, Y., Zhang, Y., and Zimmermann, H., 2025. Expedition 400 methods. In Knutz, P.C., Jennings, A.E., Childress, L.B., and the Expedition 400 Scientists, NW Greenland Glaciated Margin. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 400: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.400.102.2025

2 Expedition 400 Scientists’ affiliations.

1. Introduction

The procedures and tools employed in coring operations and in the various shipboard laboratories of the R/V JOIDES Resolution are documented here for International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 400. This information applies only to shipboard work described in the Expedition reports section of the Expedition 400 Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program volume. Methods for shore-based analyses of Expedition 400 samples and data will be described in separate individual publications. This introductory chapter describes the procedures and equipment used for drilling, coring, core handling, and sample registration; the computation of depth for samples and measurements; and the sequence of shipboard analyses. Subsequent sections describe laboratory procedures and instruments in more detail.

Unless otherwise noted, all depths in this volume refer to the core depth below seafloor, Method A (CSF-A), scale (in meters), which is equivalent to the meters below seafloor (mbsf) scale.

1.1. Operations

1.1.1. Site location and holes

GPS coordinates (WGS84 coordinate system) from precruise site surveys were used to position the vessel at each site. A Knudsen CHIRP 3260 subbottom profiler (12 kHz) was used to monitor the seafloor depth on the approach to each site. When the vessel was positioned at the site, the thrusters were lowered. Dynamic positioning control of the vessel used navigational input from the GPS, weighted by the estimated positional accuracy. The final hole position was the mean position calculated from GPS data collected over a significant portion of the time the hole was occupied.

Drill sites are numbered according to the series that began with the first site drilled by Glomar Challenger in 1968. Starting with Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 301, the prefix “U” designates sites occupied by JOIDES Resolution.

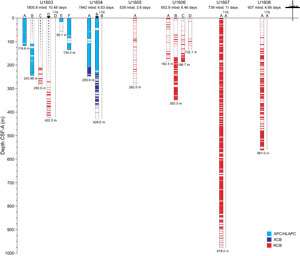

When multiple holes are drilled at a site, hole locations are typically offset from each other by ~20 m. A letter suffix distinguishes each hole drilled at the same site. The first hole drilled is assigned the site number modified by the suffix “A,” the second hole takes the site number and the suffix “B,” and so forth. During Expedition 400, 15 holes were drilled at 6 sites (U1603–U1608).

1.1.2. Coring and drilling strategy

The primary coring strategy for Expedition 400 was to core single or stratigraphically overlapping holes to provide a composite stratigraphic succession that includes preglacial conditions, a record of first growth of the northern Greenland ice sheet, and glacial and interglacial cycles. Based on the original operations plan, at the two lower slope sites we planned to use the advanced piston corer (APC) system and possibly the half-length APC (HLAPC) system in the uppermost ~250 m, followed by the extended core barrel (XCB) system to ~400 m CSF-A. At the two outer shelf sites, we planned to use the rotary core barrel (RCB) system in the first hole of each site to ~300 m CSF-A, followed by the APC/XCB systems in a second hole as permitted by the lithology. At the two Pliocene middle shelf sites, we planned to RCB core to ~400–560 m CSF-A. At the middle shelf site closest to land, we planned to RCB core in the first hole to 620 m CSF-A. The second hole was planned to begin with the installation of a hydraulic release tool (HRT) reentry system with 600 m of casing, followed by RCB coring from 600 to 978 m CSF-A. Logging was planned at all seven primary sites, including the use of the Versatile Seismic Imager (VSI) at five sites.

The coring and drilling strategy was adapted throughout the expedition to accommodate ice, recovery, and the scientific objectives. This includes RCB coring the deeper intervals of one lower slope site, deploying free-fall funnels at the lower slope sites, abandoning the second outer shelf site based on poor recovery at the first, and coring the middle shelf site closest to land without casing, among other operational changes (see Operations in each site chapter for further details).

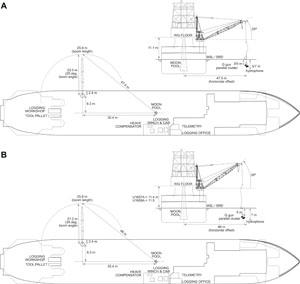

1.1.3. JOIDES Resolution standard coring systems

The APC and HLAPC coring systems cut soft-sediment cores with minimal coring disturbance relative to the other coring systems and are typically ideal for the upper portion of each hole (Figure F1). After the APC core barrel is lowered through the drill pipe and lands near the bit, the inside of the drill pipe is pressurized until failure of the two shear pins holding the inner barrel to the piston rod. The inner barrel then advances into the formation at high speed and cuts a core with a diameter of 66 mm (2.6 inches). The driller can detect a successful cut, or full stroke, from the pressure gauge on the rig floor. The assumption is that the barrel penetrated the formation by the length of core recovered (nominal recovery of ~100%), so the bit is advanced by that length before cutting the next core. The maximum subbottom depth that can be achieved with the APC system (often referred to as APC refusal) is limited by the formation stiffness or cohesion and is indicated in two ways: (1) the piston fails to achieve a complete stroke (as determined from the pump pressure reading) because the formation is too hard, or (2) excessive force (>100,000 lb; ~267 kN) is required to pull the core barrel out of the formation. Typically, several attempts are made when a full stroke is not achieved. When a full or partial stroke is achieved but excessive force cannot retrieve the barrel, the core barrel is drilled over. This means that after the inner core barrel is successfully shot into the formation, the drill bit is advanced by the length of the APC barrel (~9.6 m), thereby drilling it free from the sediment.

We deployed nonmagnetic core barrels for all APC and HLAPC cores. The downhole orientation tool was generally not deployed due to the latitude of Expedition 400 sites; however, testing of the tool was conducted in Holes U1603F and U1604B. We obtained 10 formation temperature measurements with the APC temperature (APCT-3) tool embedded in the APC coring shoe while coring Hole U1603A (Cores 4H, 7H, 10H, and 13H), Hole U1603F (Cores 4H and 10H), and Hole U1604A (Cores 4H, 7H, 10H, and 13H). These measurements are applied to calculations of the downhole temperature gradient and heat flow estimates.

The XCB corer is a rotary system with a small cutting shoe that extends below the large rotary APC/XCB bit (Figure F1). The XCB bit is able to cut a semi-indurated core with less torque and fluid circulation than the larger main bit, optimizing recovery. The XCB cutting shoe (bit) extends ~30.5 cm ahead of the main bit in soft sediment but retracts into the main bit when hard formations are encountered. The resulting cores have a nominal diameter of 5.87 cm (2.312 inches), slightly less than the 6.6 cm diameter of APC cores. XCB cores are often broken (torqued) into biscuits, which are disc-shaped pieces a few to several centimeters long with remolded sediment (including some drilling slurry) interlayering the discs in a horizontal direction and packing the space between the discs and the core liner in a vertical direction. This type of drilling disturbance may give the impression that the XCB cores have the same thickness (66 mm) as the APC cores. Although both XCB and RCB core recovery generally lead to drilling disturbance in similar sedimentary material, switching from an APC/XCB bottom-hole assembly (BHA) to an RCB BHA requires a pipe trip, adding significant time to the coring operations on site. Thus, we opted to attempt recovery with the XCB coring system as deep as possible prior to terminating operations in Holes U1604A and U1604B.

The RCB system is the most conventional rotary coring system and is suitable for lithified rock material (Figure F1). During Expedition 400, we used the RCB system exclusively for the four shelf sites (U1605–U1608). We also used the RCB system in Holes U1603C and U1603D to penetrate the deepest intervals and provide a more stable logging hole. Like the XCB system, the RCB system cuts a core with a nominal diameter of 5.87 cm. RCB coring can be done with or without the core liners used routinely with the APC/XCB soft-sediment systems.

The BHA is the lowermost part of the drill string and is typically ~130–170 m long, depending on the coring system used and total drill string length. A typical APC/XCB BHA consists of a drill bit (outside diameter = 11⁷⁄₁₆ inches), a bit sub, a seal bore drill collar, a landing saver sub, a modified top sub, a modified head sub, a nonmagnetic drill collar (for APC/XCB drilling), a number of 8¼ inch (~20.32 cm) drill collars, a tapered drill collar, six joints (two stands) of 5½ inch (~13.97 cm) drill pipe, and one crossover sub. A typical RCB BHA consists of a drill bit, a bit sub, a head sub, an outer core barrel, a top sub, a head sub, eight joints of 8¼ inch drill collars, a tapered drill collar, two stands of standard 5½ inch drill pipe, and a crossover sub to the regular 5 inch drill pipe.

Cored intervals may not be contiguous if they are separated by intervals that are drilled but not cored. During Expedition 400, we drilled ahead without coring to accelerate penetration because an interval had already been cored in an adjacent hole (Hole U1603B = 109.1 m; Hole U1603C = 211.5 m; Hole U1603D = 269.4 m; Hole U1606C = 25.0 m; Hole U1606D = 13.6 m). Holes thus consist of a sequence of cored and drilled intervals, or advancements. These advancements are numbered sequentially from the top of the hole downward. Numbers assigned to physical cores correspond to advancements and may not be consecutive.

1.1.4. Drilling disturbance

Cores may be significantly disturbed by the drilling process as well as contain extraneous material as a result of the coring and core handling process. In formations with loose granular layers (sand, ash, foraminifera ooze, chert fragments, shell hash, etc.), drilling circulation may allow granular material from intervals higher in the hole to settle and accumulate in the bottom of the hole. Such material could be sampled by the next core; thus, the uppermost 10–50 cm of each core must be assessed for potential “fall-in.”

Common coring-induced deformation includes the concave-downward appearance of originally horizontal bedding. Piston action may result in fluidization (flow-in) at the bottom of, or sometimes in, APC cores. Retrieval of unconsolidated (APC) cores from depth to the surface typically results, to some degree, in elastic rebound, and gas that is in solution at depth may become free and drive apart core segments in the liner. When gas content is high, pressure must be relieved for safety reasons before the cores are cut into segments. Holes are drilled into the liner, which forces some sediment and gas out of the liner. As noted above, XCB coring typically results in biscuits mixed with drilling slurry. RCB coring typically homogenizes unlithified core material and often fractures lithified core material.

Drilling disturbances are described in the Lithostratigraphy section of each site chapter and are indicated on the graphic core summary reports (visual core descriptions [VCDs]) in Core descriptions.

1.2. Core and section handling

1.2.1. Whole-core handling

All APC, HLAPC, XCB, and RCB cores recovered during Expedition 400 were extracted from the core barrel in plastic liners. All cores were then cut into ~1.5 m sections. The exact section length was noted and entered into the database as “created length” using the Sample Master application. This number was used to calculate recovery. Subsequent processing differed for soft-sediment and lithified material.

1.2.1.1. Sediment section handling

Headspace samples were taken from selected section ends (typically one per core) using a syringe for immediate hydrocarbon analysis as part of the shipboard safety and pollution prevention program. Whole-round samples for interstitial water (IW) analysis also were taken immediately after the core was sectioned. Sedimentary ancient DNA (sedaDNA) samples were taken from section ends following a scraping procedure to generate a clean surface (see Biostratigraphy). Core catcher samples (PAL) were taken for biostratigraphic analysis. When catwalk sampling was complete, liner caps (blue = top, colorless = bottom, and yellow = top of a whole-round sample removed from the section) were glued with acetone onto liner sections, and sections were placed in core racks for analysis.

For sediment cores, the curated length was set equal to the created length and was updated very rarely (e.g., in cases of errors or when the section length kept expanding by more than ~2 cm). Depth in hole calculations are based on the curated section length (see Depth calculations).

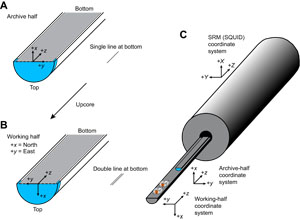

After completion of whole-round section analyses, the sections were split lengthwise from bottom to top into working and archive halves. Softer cores were split using a wire, and harder cores were split using a diamond saw. It is important to note that older material can be transported upward on the split face of a section during splitting.

1.3. Sample naming

1.3.1. Editorial practice

Sample naming in this volume follows standard IODP procedure. A full sample identifier consists of the following information: expedition, site, hole, core number, core type, section number, section half, and offset in centimeters measured from the top of the core section. For example, a sample identification of “400-U1603A-1H-2W, 10–12 cm,” represents a sample taken from the interval between 10 and 12 cm below the top of the working half of Section 2 of Core 1 (“H” designates that this core was taken with the APC system) of Hole U1603A during Expedition 400.

When working with data downloaded from the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) database or physical samples that were labeled on the ship, three additional sample naming concepts may be encountered: text ID, label ID, and printed labels.

1.3.2. Text ID

Samples taken aboard JOIDES Resolution are uniquely identified for use by software applications using the text ID, which combines two elements:

- The sample type designation (e.g., SHLF for section half) and

- A unique sequential number for any sample and sample type added to the sample type code (e.g., SHLF12641501).

The text ID is not particularly helpful to most users but is critical for machine reading and troubleshooting.

1.3.3. Label ID

The label ID is used throughout the JOIDES Resolution workflows as a convenient, human-readable sample identity. However, a label ID is not necessarily unique. The label ID is made up of two parts: the primary sample identifier and the sample name.

1.3.3.1. Primary sample identifier

The primary sample identifier is very similar to the editorial sample name described above, with two notable exceptions:

- Section halves always carry the appropriate identifier (400-U1608A-35R-2-A versus 400-U1608A-35R-2-W for archive and working halves, respectively).

- Sample top and bottom offsets relative to the parent section are indicated as “35/37” rather than “35–37 cm.”

Specific rules were set for printing the offset/offset at the end of the primary sample identifier:

- For samples taken out of the hole, core, or section, top offset/bottom offset is not added to the label ID. This has implications for the common process of taking samples out of the core catcher (CC), which technically is a section (relevant primarily for paleontology samples).

- For samples taken out of the section half, top offset/bottom offset is always added to the label ID. The rule is triggered when an update to the sample name, offset, or length occurs.

- The offsets are always rounded to the nearest centimeter before insertion into the label ID (even though the database stores higher precisions and reports offsets to millimeter precision).

1.3.3.2. Sample name

Sample name is a free text parameter for subsamples taken from a primary sample or from subsamples thereof. It is always added to the primary sample identifier following a hyphen (-NAME) and is populated from one of the following prioritized user entries in the Sample Master application:

- Entering a sample type (-TYPE) is mandatory (same sample type code used as part of the text ID; see above). By default, -NAME = -TYPE (examples include SHLF, CUBE, CYL, PWDR, etc.).

- If the user selects a test code (-TEST), the test code replaces the sample type and -NAME = -TEST. The test code indicates the purpose of taking the sample but does not guarantee that the test was actually completed on the sample (examples include PAL, TSB, ICP, PMAG, MAD, etc.).

- If the user selects a requester code (-REQ), it replaces -TYPE or -TEST and -NAME = -REQ. The requester code represents the name of the requester of the sample who will conduct postexpedition analysis.

- If the user types any kind of value (-VALUE) in the -NAME field, perhaps to add critical sample information for postexpedition handling, the value replaces -TYPE, -TEST, or -REQ and -NAME = -VALUE (e.g., SYL-80deg, DAL-40mT, etc.).

In summary, and given the examples above, the same subsample may have the following label IDs based on the priority rule -VALUE > -REQ > -TEST > -TYPE:

- 400-U1608A-35R-2-W 35/37-CYL.

- 400-U1608A-35R-2-W 35/37-PMAG.

- 400-U1608A-35R-2-W 35/37-DAL.

- 400-U1608A-35R-2-W 35/37-DAL-40mT.

When subsamples are taken out of subsamples, the -NAME of the first subsample becomes part of the parent sample ID and another -NAME is added to that parent sample label ID:

For example, a thin section billet (sample type = TSB) taken from the working half at 2–4 cm offset from the section top might result in a label ID of 400-U1608A-20R-1-W 2/4-TSB. After the thin section was prepared (~48 h later), a subsample of the billet might receive an additional designation of TS49, which would be the forty-ninth thin section made during the expedition. A resulting thin section label ID might therefore be 400-U1608A-20R-1-W 2/4-TSB-TS_49.

1.4. Depth calculations

Sample and measurement depth calculations were based on the methods described in IODP Depth Scales Terminology (version 2.0) at https://www.iodp.org/policies-and-guidelines/142-iodp-depth-scales-terminology-april-2011/file (Table T1). The definition of multiple depth scale types and their distinction in nomenclature should alert the user that a nominal depth value on two different depth scale types (and even two different depth scales of the same type) generally does not refer to exactly the same stratigraphic interval in a hole. The SI unit for all depth scales is meters (m).

Depths of cored intervals were measured from the drill floor based on the length of drill pipe deployed beneath the rig floor and referred to as drilling depth below rig floor (DRF), traditionally referred to as meters below rig floor (mbrf). The depth of each cored interval, measured on the DRF scale, can be referenced to the seafloor by subtracting the seafloor depth measurement (DRF) from the cored interval (DRF). This seafloor-referenced depth of the cored interval is referred to as the drilling depth below seafloor (DSF), traditionally mbsf. In the case of APC coring, the seafloor depth was the length of pipe deployed minus the length of the mudline core recovered. In the case of RCB coring, the seafloor depth was adopted from a previous hole drilled at the site or by tagging the seafloor.

Depths of samples and measurements in each core were computed based on a set of rules that result in a depth scale type referred to as CSF-A. The two fundamental rules are that (1) the top depth of a recovered core corresponds to the top depth of its cored interval (top DSF = top CSF-A), regardless of type of material recovered or drilling disturbance observed, and (2) the recovered material is a contiguous stratigraphic representation even when core segments are separated by voids when recovered, the core is shorter than the cored interval, or the amount of material missing between core pieces is unknown. When voids were present in the core on the catwalk, they were closed by pushing core segments together whenever possible. The length of missing core should be considered a depth uncertainty when analyzing data associated with core material.

When core sections were given their curated lengths, they were also given a top and a bottom depth based on the core top depth and the section length. Depths of samples and measurements on the CSF-A scale were calculated by adding the offset of the sample (or measurement from the top of its section) to the top depth of the section.

Per IODP policy established after the introduction of IODP Depth Scales Terminology version 2.0, sample and measurement depths on the CSF-A depth scale type are commonly referred to with the custom unit mbsf, just like depths on the DSF scale type. The reader should be aware, though, that the use of mbsf for different depth scales can cause confusion in specific cases because different “mbsf depths” may be assigned to the same stratigraphic interval. For example, a soft-sediment core from less than a few hundred meters below seafloor often expands upon recovery (typically by a few percent to as much as 15%), and the length of the recovered core exceeds that of the cored interval. Therefore, a stratigraphic interval in a particular hole may not have the same depth on the DSF and CSF-A scales; thus, throughout this volume the CSF-A depth scale is used unless otherwise noted. When recovery in a core exceeds 100%, the CSF-A depth of a sample taken from the bottom of the core will be deeper than that of a sample from the top of the subsequent core (i.e., some data associated with the two cores overlap on the CSF-A scale). To overcome the overlap problem, core intervals can be placed on the core depth below seafloor, Method B (CSF-B), depth scale. The Method B approach scales the recovered core length back into the interval cored, from >100% to exactly 100% recovery. If cores had <100% recovery to begin with, they are not scaled. When downloading data using the JOIDES Resolution Science Operator (JRSO) LIMS Reports pages (http://web.iodp.tamu.edu/LORE), depths for samples and measurements are by default presented on both the CSF-A and CSF-B scales. The CSF-B depth scale can be useful for data analysis and presentations at sites with a single hole.

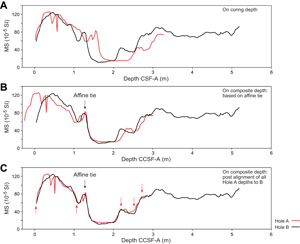

A core composite depth below seafloor (CCSF) scale can be constructed to mitigate inadequacies of the CSF-A scale for scientific analysis and data presentation (see Stratigraphic correlation). The most common application is the construction of a CCSF scale from multiple holes drilled at a site using depth shifting of correlative features across holes. This method not only eliminates the CSF-A core overlap problem but also allows splicing of core intervals such that gaps in core recovery, which are inevitable in coring a single hole, are essentially eliminated and a continuous stratigraphic representation is established. This depth scale type was used at Sites U1603, U1604, U1607, and U1608 during Expedition 400.

A CCSF scale and stratigraphic splice are accomplished by downloading correlation data from the expedition (LIMS) database using the Correlation Downloader application, correlating stratigraphic features across holes using Correlator or any other application, depth-shifting cores to create an affine table with an offset for each core relative to the CSF-A scale, and creating a splice interval table that defines which core intervals from the participating holes make up the stratigraphic splice. Affine and splice interval tables can be uploaded to the LIMS database, where internal computations create a CCSF depth scale. The CCSF depth can then be added to all subsequent data downloads from the LIMS database, and data can be downloaded for a splice.

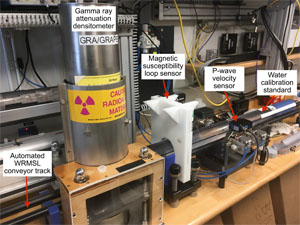

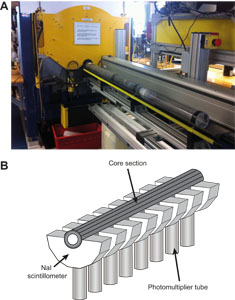

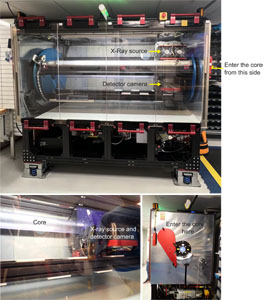

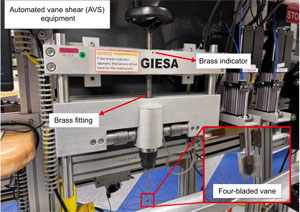

1.5. Shipboard core analysis

Whole-round core sections were immediately run through the Whole-Round Multisensor Logger (WRMSL), which measures P-wave velocity, density, and magnetic susceptibility (MS), and the Natural Gamma Radiation Logger (NGRL). After letting cores thermally equilibrate for at least 4 h, thermal conductivity measurements were also taken before the cores were split lengthwise into working and archive halves. In select holes, Rhizon samples were collected in the upper ~20 m CSF-A from whole-round core sections (see Geochemistry). The working half of each core was sampled for shipboard analysis, routinely for paleomagnetism and physical properties and more irregularly for geochemistry and biostratigraphy. The archive half of each core was scanned on the Section Half Imaging Logger (SHIL) and the X-Ray Linescan Logger (XSCAN). Archive halves were also measured for color reflectance and MS on the Section Half Multisensor Logger (SHMSL). The archive halves were described macroscopically and microscopically in smear slides. Finally, the archive halves were run through the cryogenic magnetometer. Both halves of the core were wrapped and then put into labeled plastic tubes that were sealed and transferred to cold storage space aboard the ship.

A total of 5882 samples were taken for shipboard analysis. At the end of Expedition 400, all archive section halves of the cores were shipped to the Gulf Coast Repository in preparation for X-ray fluorescence (XRF) core scanning. Working section halves and all other residues were shipped to the Bremen Core Repository for a shore-based sampling party in March 2024. All sections and samples will be permanently stored in the Bremen Core Repository.

2. Lithostratigraphy

Sediments and rocks recovered during Expedition 400 were described macroscopically from core archive section halves and microscopically from smear slides and thin sections. Observations were recorded in separate macroscopic and microscopic GEODESC templates. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses of both clay mineral and bulk preparations were done from the working half of the section. Color spectrophotometry, point-source MS (MSP) measurements, and X-ray and linescan camera imaging of core archive section halves were also carried out by the lithostratigraphy group. Methods associated with X-ray imaging are described in Physical properties. Methods associated with shipboard measurements of carbonate and organic matter (carbon-hydrogen-nitrogen-sulfur [CHNS]) of sediment samples selected by the lithostratigraphy group are described in Geochemistry.

2.1. Section-half images

The technique used for splitting cores into working and archive halves (either using a piano wire or a saw from the bottom to the top; see Introduction) affects the appearance of the split core surface. Before core description and high-resolution digital color imaging, the quality of the split core surface of the archive half of each core was assessed. When necessary (e.g., if the surface was irregular or smeared), the split core surface was scraped lightly with a glass microscope slide or stainless steel plate to even the surface.

2.1.1. Photography and color imaging

The surface of the cleaned archive half was imaged using the SHIL. Imaging was conducted as soon as possible after splitting to avoid sediment color changes caused by oxidation and drying. In cases of watery or soupy sediment, the surface was allowed to dry sufficiently prior to scanning to avoid excessive light reflection and overexposure. The SHIL captures continuous high-resolution images for analysis and description, using three pairs of advanced illumination, high-current, focused light-emitting diode (LED) line lights to illuminate the core. Each of the LED pairs has a color temperature of 6,500 K and emits 200,000 lux at 7.6 cm. Digital images were taken using a linescan camera (manufactured by JAI) at an interval of 10 lines/mm to create a high-resolution image file. The camera height was set such that each pixel imaged a 0.1 mm2 section of the core surface, but the actual core width per pixel can vary because of slight differences in the section-half surface height. Low-resolution cropped raster files of the core section surface and high-resolution raster files with a grayscale and depth ruler were created from the image files.

2.1.2. Spectrophotometry and colorimetry

The SHMSL employs multiple sensors to measure bulk physical properties in a motorized and computer-controlled instrument track. The sensors included in the SHMSL are a spectrophotometer, an MSP sensor, and a laser surface analyzer. During this expedition, the point measurement interval for the spectrophotometer and the MSP sensor measurements was 2 cm for all sections. To achieve a flush contact between point sensors and the split core surface and to avoid sediment transfer to the instrument surfaces, archive halves were covered with clear plastic wrap prior to measurement. The laser surface analyzer helps recognize irregularities in the split core surface (e.g., cracks and voids), whereas data from this tool were recorded to provide an independent check on SHMSL measurement fidelity. MS was measured using a Bartington Instruments MS2 meter and an MS2K contact probe (see Physical properties). Reflectance spectroscopy (spectrophotometry) was carried out using an Ocean Optics QE Pro detector, which measures the reflectance spectra of the split core from the ultraviolet to near-infrared range. Each measurement was recorded in 2 nm spectral bands from 390 to 732 nm. The data were converted to the L*a*b* color space system, which expresses color as a function of lightness (L*; grayscale, where more white is positive and more black is negative) and color values a* and b*, where a* reflects the balance between red (positive a*) and green (negative a*) and b* reflects the balance between yellow (positive b*) and blue (negative b*).

2.2. Sedimentological core description

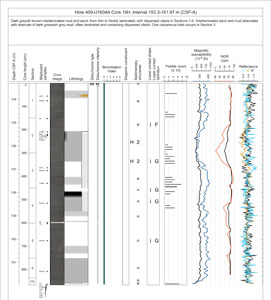

Macroscopic descriptions of each section (nominally 0–150 cm long) were recorded on handwritten core description forms (barrel sheets) that include color images collected using the SHIL (Figure F2). All handwritten sheets were scanned and digitally preserved (see LITH in Supplementary material). Standard sedimentological observations of lithology, primary and secondary (i.e., syn- and postsedimentary deformation) sedimentary structures, bioturbation intensity, macroscopic biogenic remains (e.g., shell fragments and plant matter), diagenetic features, drilling disturbance type and intensity, clast counts (>5 mm diameter), character of the lower contact, and shipboard archive-half sample types and depths were recorded in individual columns on the barrel sheets. Color (Munsell Color Company, 2010), shape, and compositional characteristics of coarse clasts (>2 cm) were recorded as comments. The identification of distinct sedimentary features or core intervals was supported by inspection of physical property data, including whole-round core measurements of MS and natural gamma radiation (NGR) (see Physical properties), as well as split core MSP and color reflectance. As an example, reduced MS and lower density could be used to delineate biogenic-rich intervals.

2.2.1. GEODESC data capture software

Data from the handwritten core description sheets were compiled and entered into the LIMS database using GEODESC software. A macroscopic template was developed in GEODESC Template Manager for Expedition 400 and includes the following categories:

- Drilling disturbance (type and intensity),

- Lithology (major lithology, with prefix and suffix modifiers indicating variable biogenic content, matrix grain size, clast abundance, degree of consolidation, and other characteristics),

- Strata thickness (if stratification is present),

- Sedimentary structures,

- Bioturbation intensity,

- Macrofossils,

- Diagenetic constituents/composition,

- Clast counts (number of lithic clasts >5 mm and characteristics of clasts >2 cm), and

- Lower contact (shape, definition, and attitude).

A separate template was made to capture clast counts per 10 cm interval for clasts with diameters >5 mm. Four additional GEODESC templates were constructed for (1) hole/site summary (lithostratigraphic units and age), (2) core summary (written description of major lithologic findings by core), and two microscopic templates for (3) smear slides and (4) thin sections. The microscopic templates describe the relative abundance of major lithogenic and/or biogenic components and minor constituents. The thin section template provides a summary overview and links to images. All information entered into GEODESC was subsequently uploaded to the LIMS database (accessible via GEODESC Data Access) and was used as input to a simplified one-page VCD graphical report for each core.

2.2.2. Drilling disturbance

Core disturbance from the drilling process was characterized and modified from the nomenclature of Jutzeler et al. (2014) and entered into GEODESC (Table T2). The intensity of drilling disturbance was also entered into GEODESC and displayed graphically on the VCDs. The intensity of drilling disturbance of unconsolidated and consolidated sediments was classified into five categories: undisturbed, slightly, moderately, strongly, and severely.

In unconsolidated sediments, the five categories imply the following:

- 0 = undisturbed.

- 1 = slightly disturbed: bedding contacts are slightly bent or bowed in a concave-downward appearance.

- 2 = moderately disturbed: bedding contacts are bent or bowed in a concave-downward appearance but are still visible and in the correct stratigraphic order.

- 3 = strongly disturbed: core has some portions that are completely deformed and may not maintain stratigraphic order.

- 4 = severely disturbed: bedding is completely deformed and may show diapiric or flow structures.

In harder sediments (i.e., consolidated by compaction or cementation), the five categories are defined as follows:

- 0 = undisturbed.

- 1 = slightly fractured: core pieces are in place and have very little drilling slurry or brecciation.

- 2 = moderately fractured or biscuited: core pieces are in the correct stratigraphic sequence (although the entire section may not be represented); on occasion, intact core pieces are broken into rotated discs (or biscuits) as a result of the drilling process, and drilling mud has possibly flowed in.

- 3 = strongly fractured: core pieces are probably in correct stratigraphic sequence (although the entire section may not be represented); frequently, intact core pieces are broken into rotated discs (or biscuits) as a result of the drilling process, and drilling mud has possibly flowed in.

- 4 = severely fractured or brecciated: pieces are from the cored interval but may not occur in the correct stratigraphic sequence within the core.

2.3. Lithologic classification scheme

Lithologic descriptions were based on the classification schemes described in the Methods chapters for other high-latitude, glaciated-margin drilling expeditions such as Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Leg 178 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1999), the Cape Roberts Project (Hambrey et al., 1997), the Antarctic Drilling Project (ANDRILL; Naish et al., 2006), Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expeditions 318 (Expedition 318 Scientists, 2011) and 341 (Jaeger et al., 2014), and IODP Expeditions 374 (McKay et al., 2019) and 379 (Gohl et al., 2021).

2.3.1. Principal names and modifiers

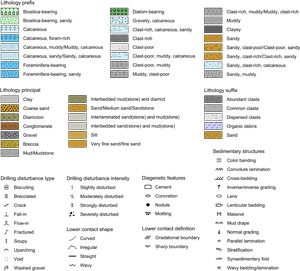

The principal lithologic name was assigned based on the relative abundances of nonbiogenic (i.e., terrigenous, detrital carbonate) and biogenic grains (Figure F3). The principal name is purely descriptive and does not include interpretive classifications relating to fragmentation, transport, deposition, or alteration processes. The principal name entered into GEODESC of a sediment/rock with >50% terrigenous grains is based on an estimate of the grain sizes present (Figure F3A). The Wentworth (1922) scale was used to define size classes of clay, silt, sand, and gravel.

If no gravel is present, the principal sediment/rock name was determined based on the relative abundances of sand, silt, and clay. The term “mud” is used to define sediments containing a mixture of silt and clay that could not be reliably differentiated using visual macroscopic inspection (e.g., silty mud, clayey mud, or sandy mud) (Mazzullo et al., 1988; Shepard, 1954) (Figure F3B). Sandy mud to muddy sand describes sediment composed of a mixture of at least 20% each of sand, silt, and clay (Figure F3B). The prefix was determined by the percentage >50% of sand versus mud in the matrix (Figure F3B).

If the sediment/rock contains siliciclastic gravel, then the principal name was determined from the relative abundance of gravel (>2 mm; also referred to as “clasts”) and sand/mud ratio of the matrix following a modified version of the textural classifications of Moncrieff (1989) as outlined in Marsaglia and Milliken (2023), with gravel percent estimated using the comparison chart of Terry and Chilingar (1955) (Figure F3C). The term “diamicton/diamictite” is used as a nongenetic term for unsorted to poorly sorted terrigenous sediment that contains a wide range of particle sizes. The name “diamicton” is used for unlithified, poorly sorted sediment, whereas “diamictite” is used for the lithified type. Accordingly, a clast-poor muddy diamicton includes 5%–10% gravel (>2 mm) and 25%–50% sand in matrix, whereas a clast-rich muddy diamicton includes 10%–30% gravel and 25%–50% sand in matrix. A clast-poor sandy diamicton has 5%–10% gravel and 50%–75% sand in matrix. For a clast-rich sandy diamicton, gravel content is 10%–30%, sand content is 50%–75%, and the remainder is mud. The terms “gravel/conglomerate/breccia” are used when the matrix includes >30% gravel, with conglomerate describing a sediment with dominantly (well) rounded gravel grains and breccia describing a sediment with dominantly (very) angular gravel grains (Figure F3). If clasts (>2 mm) are present but less than 5% in abundance, the term “dispersed clasts” is used as a lithology suffix, following the principal lithology name. If there is 25% or less sand or mud (combined clay and silt) with clasts (>2 mm) present, the principal lithology is named for the siliciclastic component with common clasts (5%–10%) or abundant clasts (10%–30%) (e.g., sandy mud with common clasts).

The principal name of sediment with >50% biogenic grains is ooze, modified by the most abundant biogenic grain type (Figure F3A). For example, if diatoms exceed 50%, then the sediment is called diatom ooze. However, if the sediment is a mixture of biogenic siliceous material (e.g., diatoms, spicules, radiolaria, etc.) with none of the biogenic component exceeding 50% in abundance, then the sediment is termed biosiliceous ooze. The same principle applies to calcareous microfossils (e.g., foraminifera ooze versus calcareous ooze).

The prefix “calcareous” is used for sediments dominated by detrital carbonate. In all instances for this expedition, calcareous lithologies are composed of abiogenic silt-sized crystalline or micrite grains. Where no material is present, the type (void, whole round, gas expansion, or other) and depth range is recorded in GEODESC.

For all lithologies, we applied major and minor modifiers to the principal sediment/rock names modified from the biogenic-pelagic scheme in the Expedition 379 methods (Gohl et al., 2021) (Figure F3A):

- Minor biogenic modifiers are those components with abundances of 10%–25% and are indicated by the suffix “-bearing” (e.g., diatom-bearing).

- Major biogenic modifiers are those components that comprise 25%–50% of the grains and are indicated by the suffix “-rich” (e.g., diatom-rich).

- Siliciclastic modifiers in biogenic oozes are those components with abundances of 10%–50% and are indicated by the terrigenous modifier “-y” (e.g., silty, muddy, or sandy).

2.3.2. Sedimentary structures

The locations and types of sedimentary structures visible on the prepared surfaces of the archive section halves were entered into the macroscopic GEODESC template under strata thickness, sedimentary structures (syndeposition), and deformational structures (postdeposition). Lower contacts (basal boundaries) between different lithologies are classified as curved, irregular, straight, and wavy. Bedding and lamination are defined following Mazzullo et al. (1988) as follows:

- Thinly laminated (≤3 mm thick),

- Lainated (3 mm to 1 cm thick),

- Very thinly bedded (1–3 cm),

- Thinly bedded (3–10 cm),

- Medium bedded (10–30 cm),

- Thickly bedded (30–100 cm), and

- Very thickly bedded (>100 cm).

For units in which two lithologies are interbedded or interlaminated (i.e., where individual beds [layers >1 cm thick] or laminae [layers <1 cm thick] alternate between one lithology and another), the terms “interbedded” or “interlaminated” were added before the lithology names and are considered a primary lithology (e.g., interbedded sand and mud and interbedded mud and diamicton). This terminology is for ease of data entry and graphic log display purposes. When discrete beds of one lithology occur within a thicker interval of another lithology (e.g., centimeter- to decimeter-thick sand beds within a mud bed), those discrete beds were logged individually, and the associated bed thickness and grain size ranges were described.

Grading within beds and laminae was also described. Normal grading corresponds to layers with an upward decrease in grain size, whereas inverse/reverse grading corresponds to layers with an upward increase in grain size.

Deformational features that are unrelated to drilling disturbance were recorded in notes on the barrel sheets, in GEODESC, and as symbols on the VCDs. Symbols include both synsedimentary deformation structures (e.g., flame structures) and postdepositional features (e.g., faults). When possible, to determine apparent motion sense for faults with certainty, the direction of displacement (i.e., reverse or normal) was recorded in GEODESC and on the barrel sheets but is not displayed systematically on the VCDs.

Where sediments are diagenetically altered (e.g., mottling or the presence of pyrite, concretions, or cement), the diagenetic feature was selected from a predefined list in the Diagenetic constituent column of the GEODESC template. We define mottles (millimeter to centimeter scale) as spots or smears where material has a different color than the surrounding sediment.

Interval thickness is recorded from the uppermost to the lowermost extent of the described feature, as well as in the Comments column of the core barrel sheet.

2.3.3. Bioturbation

Ichnofabric description included the extent of bioturbation and notation of distinctive biogenic structures. To assess the degree of bioturbation semiquantitatively, we used the Droser and Bottjer (1986) ichnofabric index (0–6):

- 0 = bioturbation absent.

- 1 = sparse bioturbation (bedding distinct, few discrete traces).

- 2 = uncommon bioturbation (bedding distinct, low trace density).

- 3 = moderate bioturbation (bedding boundaries sharp, traces discrete with rare overlap).

- 4 = common bioturbation (bedding boundaries indistinct, high trace density with common overlap).

- 5 = abundant bioturbation (bedding just visible though completely disturbed).

- 6 = complete bioturbation (total biogenic homogenization of sediment).

The ichnofabric index is graphed using the numerical scale in the Bioturbation column of the graphical logs. Descriptions of the bioturbation were made in the Bioturbation comments column in the GEODESC template. When identifiable, ichnofacies (Ekdale et al., 1984) were noted and logged in the Interval comment column of the macroscopic GEODESC template.

2.3.4. Macroscopic biogenic components and diagenetic features

Paleontologic and diagenetic features other than those delineated above were recorded on the barrel sheets, and descriptions were entered in the corresponding columns of the GEODESC template. These features include, for example, macroscopic biogenic remains (e.g., skeletal and organic debris) and concretions. When possible, concretions were described by composition.

2.3.5. Clast abundance and characteristics

Coarse gravel abundance was determined by counting the clasts >5 mm in diameter visible on the surface of the archive half in 10 cm depth intervals. Where only holes or depressions caused by lithic clasts were observed, the working half was also examined to determine pebble abundance. If between one and nine individual clasts were counted per 10 cm depth interval, the number of clasts per interval was entered into GEODESC in the Clast count column. If 10 or more clasts were present in a 10 cm interval, the number 10 was entered in the Clast column.

Details on lithology, size, shape, rounding, and surface texture (e.g., striae or faceted faces) on clasts with a long axis >2 mm are provided in the core description sheets and in the Interval comments column in GEODESC.

2.4. Microscopic descriptions

2.4.1. Smear slides

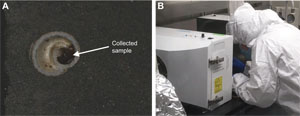

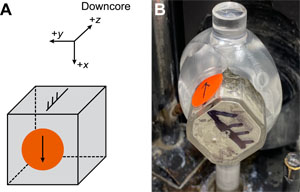

To aid in lithologic classification, the size, composition, and abundance of sediment constituents were estimated microscopically using smear slides (Figure F4). For each smear slide, a small amount of sediment was removed from the archive section half using a wooden toothpick and put on glass. The sediment was mixed with deionized water and evenly spread. To reduce the water droplet tension and aid in disaggregating clays, soap or saliva was used. The dispersed sample was dried on a hot plate at a moderate setting (150°C). A drop of Norland Optical Adhesive Number 61 was used to glue a coverslip to the slide. The smear slide was then placed in an ultraviolet light box for at least 15 minutes to cure the adhesive.

Smear slides were examined with a transmitted-light petrographic microscope equipped with a standard eyepiece micrometer. Biogenic and mineral components were identified following standard petrographic techniques as stated in Rothwell (1989), Marsaglia et al. (2013), and Marsaglia et al. (2015). Several fields of view (FOVs) were examined at 50×, 100×, 200×, 400×, and 500× magnification to assess the abundance of detrital, biogenic, and authigenic components. The relative abundance percentages of the sedimentary constituents were visually estimated using the techniques of Rothwell (1989). The texture of siliciclastic lithologies (e.g., the relative abundance of sand-, silt-, and clay-sized grains) and the proportions and presence of biogenic and mineral components were recorded in the smear slide worksheet and entered into the microscopic GEODESC template.

Components observed in smear slides are categorized as follows:

- T = trace (≤1%).

- R = rare (>1%–10%).

- C = common (>10%–25%).

- A = abundant (>25%–50%).

- D = dominant (>50%).

Very fine and coarse grains are difficult to observe in smear slides, and their relative proportions in the sediment can be affected during slide preparation. Therefore, intervals dominated by sand-sized and larger constituents were examined by macroscopic comparison to grain size reference charts. Photomicrographs of some smear slides (e.g., representative lithologies) were acquired and uploaded to the LIMS database.

2.4.2. Thin sections

The descriptions of sediments and rocks were complemented with thin section analysis (Figure F5). Standard thin section billets were cut from selected intervals or features as needed, and thin sections prepared on board were examined with a transmitted-light petrographic microscope equipped with a standard eyepiece micrometer. Data were entered into the Thin section summary template for GEODESC. Photomicrographs of thin sections were acquired and uploaded to the LIMS database.

2.5. X-ray diffraction analysis

XRD analysis was performed on both bulk sediment and clay (<4 µm) separates to determine their mineralogy. A 5 cm3 sample was taken from the working section halves at variable intervals, depending on the site. Sample positions for bulk and clay fraction XRD were selected based on visual core observations (e.g., color variability, visual changes in lithology and texture, etc.) and smear slide investigations. The sampling objective was to characterize the mineralogy for distinct lithologic units (or subunits) or detect changes above and below transitions and unconformities.

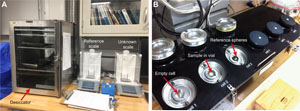

For bulk sediment analysis, samples were freeze-dried and stored in a desiccator to prevent reabsorption of moisture. Freeze-dried samples were finely ground using an appropriate mortar and pestle size.

Clay fractions were prepared according to procedures outlined in the Expedition 318 methods (Expedition 318 Scientists, 2011). For these preparations, a ~2 g sample was placed in a 50 mL centrifuge tube with 10% acetic acid, sonicated for 15 min, and allowed to stand for 1 h to remove carbonate material. After centrifuging for 15 min at 1500 rpm, the acetic acid was decanted, 25 mL of distilled water was added, the sample was centrifuged again, and the water was decanted. This washing procedure was repeated two more times to remove both the acid and salts from the sample. After decanting the final wash, 25 mL of 1% sodium hexametaphosphate solution was added to the sample in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. The sample was then placed in a dismembrator for 5 min to suspend the clays and then centrifuged for 4 min at 750 rpm twice to settle the >4 µm particles. The clays that remained in suspension were removed from the top ~1 cm of the centrifuge tube and centrifuged for 1 h at 3000 rpm. Three subsamples were pipetted directly onto amorphous quartz sample discs. These sample discs were then left to air dry in a desiccator. After drying, one disc was analyzed and the other was solvated with ethylene glycol for ~12 h and reanalyzed to determine the presence of expandable clays. The third subsample was heated in a muffle furnace at 550°C over 4 h before being analyzed to check for the presence of kaolinite.

Prepared samples were top-mounted onto a sample holder and analyzed using a Malvern Panalytical AERIS X-ray diffractometer mounted with a PIXcel1D-Medipix3 detector using nickel-filtered CuKα radiation. XRD instrument settings for clay samples were as follows:

- Voltage = 40 kV.

- Current = 40 mA.

- Goniometer scan = air dried, 5°–15.5°2θ (step size = 0.016599°2θ); glycolyzed, 1.5°–34.5°2θ (step size = 0.016599°2θ) and 24°–45.01°2θ (step size = 0.0085°2θ) for resolving the (002) peak of kaolinite from the (004) peak of chlorite; and heated, 1.5°–34.5°2θ (step size = 0.0108664°2θ).

- Scan speed = 109.65 s/step.

- Divergence slit = ⅛°.

XRD instrument settings for bulk samples were as follows:

- Voltage = 40 kV.

- Current = 40 mA.

- Goniometer scan = 5°–90°2θ (step size = 0.0108664°2θ).

- Scan speed = 80.3255 s/step.

- Divergence slit = ¼°.

Diffractograms of bulk samples were evaluated with the HighScore Plus software package (version 4.8), which allowed for mineral identification and basic peak characterization (e.g., baseline removal and maximum peak intensity). Files were created that contained d-spacings, diffraction angles, and peak intensities with the background removed. These files were screened for d-spacings characteristic of a limited range of minerals that were expected to be present in the sediments (Table T3). Peak intensities from those selected minerals were reported to provide a semiquantitative measure of their variations downhole. The semiquantitative results were calculated from the peak intensities expressed as a percentage of the sum of all primary peak intensities of the targeted minerals. These percentages were qualified as follows:

Secondary diffraction peaks were not checked to ensure that there were no false identifications. Thus, if the peak of a rare mineral fell within the detection window of a mineral to be identified, then the identification of the mineral will be wrong. Also, there were peaks on the XRD patterns that did not match the minerals being searched, and the materials responsible for those peaks have not yet been identified. Digital files with the diffraction patterns as well as raw XRD files are available in the LIMS database.

Relative abundances of the major clay mineral groups (smectite, chlorite, illite, and kaolinite) were established on the basis of the main peak intensity from the glycolated analysis. The air-dried and heated spectra were not interpreted on board but are available in the LIMS database. The shipboard results were interpreted semiqualitatively based on the relative peak intensities of the most common clay components. The ratio of the peak intensity of identified clay is presented as a first estimation of the clay ratio in the sediments.

2.6. Core description

2.6.1. Lithostratigraphic units

At each site, units were assigned to packages of reoccurring lithologies to highlight major lithologic changes downhole. Units were established where a prominent change in recurring sediment lithology, clast abundance, sedimentary structures, color, or macroscopic constituents was observed, generally on the scale of tens of meters. Lithostratigraphic units are numbered beginning at the top of the stratigraphic succession using Roman numerals. When notable but more subtle changes were observed, units were divided into subunits. Subunits are distinguished from the main lithologic units by adding a letter to the unit number (e.g., Subunit IA).

2.6.2. Standard graphical report

VCDs are generated for each core using the Strater software package (Golden Software) (Figure F6). Sample identification (expedition, hole, core, and section) is included at the top of each VCD, along with a summary core description. To the left of the graphic in the Lithology column, VCDs display the depth CSF-A (in meters), core length (in centimeters), section, location of shipboard samples, and the SHIL digital color image. Columns to the right of Lithology provide the type and intensity of drilling disturbance, bioturbation intensity, sedimentary structures, lower contact descriptions, and clast abundance (when appropriate for a given site), and may include physical property data (MS, gamma ray attenuation [GRA], and NGR) collected using the WRMSL and SHMSL (see Physical properties) (Figure F6). Graphic lithologies, sedimentary structures, and other visual observations shown on the VCDs by graphic patterns and symbols are explained in Figure F7. Lithologic symbols are simplified for hole and site summary graphic logs, for which individual legends are provided.

3. Biostratigraphy

Biostratigraphy is based on planktonic foraminifera, benthic foraminifera, diatoms, and dinoflagellate cysts (dinocysts), which were studied in core catcher samples from all sites. Additional samples were taken from split core sections at some sites, targeting lithofacies variations suggestive of improved microfossil preservation (e.g., where color and/or physical properties data suggest calcareous, biosilica-rich, or organic-rich intervals). Samples from Expedition 400 were processed and analyzed for microfossil content shipboard during the expedition. Core catcher dinocyst assessments will be updated as part of initial shore-based work using hydrofluoric acid digestion approaches to concentrate palynomorphs, a method that was not available during this expedition. At high latitudes, where standard zonal markers are often absent, integration of microfossil groups is crucial for even the coarsest of chronological frameworks.

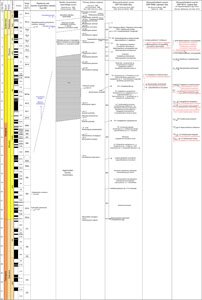

Biostratigraphy is aimed at identification of biostratigraphic horizons (biohorizons) in the cores, which might delimit established biozones. Ideally, the bioevents involve the first occurrence (FO) or last occurrence (LO) of a species and/or the first or last common occurrence (FCO or LCO) of a species. In reality, because of highly discontinuous microfossil occurrences at Expedition 400 sites, as a consequence of preservation and environmental factors influencing the Greenland margin, often only fragmentary perspectives on species ranges are available, especially in the case of foraminifera and diatoms. Therefore, during Expedition 400, we were unable to apply established biozone schemes, even regional versions constructed for the northern high latitudes. We were, however, able to recognize some biohorizons, including a selection of primary and accessory markers that have been defined in existing zonation schemes. Biohorizons are assumed to result from biological events (bioevents) in the past, such as migrations, extinctions, and evolutionary transitions. These bioevents have been previously assigned absolute ages, ideally referenced to the paleomagnetic reversal sequence. However, few Cenozoic bioevents recognized in the northern polar latitudes are well calibrated. Moreover, listed bioevent ages may not be accurate for the cored sites because of diachrony and/or imprecise calibration at the Arctic latitudes of Baffin Bay, for which no detailed and tested zonation schemes exist. Nevertheless, identification of biohorizons in stratigraphic order allowed us to contribute to age-depth modeling. Details of the biostratigraphic schemes and markers used for the various groups are outlined in their respective sections below and compiled in Figure F8.

There were no dedicated calcareous nannofossil or benthic foraminifera biostratigraphy specialists on board during Expedition 400. However, because planktonic foraminifera are extremely scarce, benthic foraminifera became a primary chronostratigraphic guide and, thus, an overview of the benthic foraminifera was attempted. Similarly, where relevant, general observations of calcareous nannofossil presence/absence in smear slides was recorded by the Expedition 400 diatom team in consultation with sedimentologists during smear slide description. These slides and observations could be of future interest to a calcareous nannofossil specialist. Bolboformids, which are useful for biostratigraphy in other regions of the northern North Atlantic, are not found in the studied samples recovered during Expedition 400.

Where possible, for each site and each fossil group a list of identified biohorizons was prepared. These age constraints are plotted against depth in the accompanying age-depth plots where appropriate. Biohorizon lists and age-depth plots were not produced for Sites U1603–U1605 due to the scarcity of microfossils and limited time coverage at those sites. Because we never captured actual bioevents (e.g., LOs or FOs), constraints in the age-depth plots involve bars or boxes representing the total age range of a key taxon recognized at the stated depth. The biostratigraphic age information was used in conjunction with the paleomagnetic reversal records to construct integrated biomagneto age-depth models for each site. For each site, the paleomagnetic and biostratigraphic data were collated on a common geological timescale. The timescale used for Expedition 400 is mostly taken from Ogg (2020), which was published as part of the Geologic Time Scale 2020 (Gradstein et al., 2020). For subdivision of the formal series of the timescales and their geochronologic equivalent epochs, we use capitalized subseries (e.g., Lower Pleistocene) and subepochs (e.g., Early Pliocene) according to Aubry et al. (2024). Lowercase is used when referring to strata (e.g., lower Pliocene) and time (e.g., late Miocene) when a stage/age has not been constrained. The lowercase modifier emphasizes their informal status. All semiquantitative microfossil abundance data produced shipboard were input to GEODESC and are available for each site (https://iodp.tamu.edu/DataAccess/).

3.1. Planktonic foraminifera

3.1.1. Taxonomy and zonal scheme

Previous drilling of Miocene age to recent sediments of the high-latitude North Atlantic and the Subarctic and central Arctic Oceans tells us that few of the planktonic foraminifera marker species that are used in the standard global tropical to subtropical biozonation would be present at Expedition 400 sites, which lie along a continental shelf to slope transect at ~74°N. If present, they are likely only occasional immigrants; thus, their appearance may not represent a truly global evolutionary event. The possibility of lower latitude species making appearances is considered more likely for the Oligocene–Pliocene epochs, when latitudinal climatic gradients were weaker than in the Pleistocene. Nevertheless, we referred to existing high northern latitude planktonic biostratigraphic frameworks that have been developed over the past 50 years.

There have been repeated efforts to develop regionally applicable planktonic foraminifera biostratigraphic schemes for the North Atlantic, the Nordic Seas, and the North Sea based on endemic cold-water–tolerant taxa (Poore and Berggren, 1975; Poore, 1979; Weaver and Clement, 1986; King, 1989; Spiegler and Jansen, 1989; Gradstein and Backstrom, 1996; Spiegler, 1996; Flower, 1999; Anthonissen, 2009, 2012; Sierro et al., 2009). For Expedition 400, the biostratigraphic challenges were a general paucity of calcareous microfossils combined with low species diversity, consistent with the few previous long-term Cenozoic Arctic coring attempts at northern high latitudes. ODP Leg 151, which reached 80°N on the Yermak Plateau, found common planktonic foraminifera only in the Pleistocene, in the form of Neogloboquadrina pachyderma–dominated assemblages, with strong abundance variability over glacial cycles (Spiegler, 1996). Calcareous fossils disappeared rapidly downsection during the Pliocene and were almost entirely absent in the Miocene to Eocene (Spiegler, 1996), a pattern exaggerated in the central Arctic Ocean, where calcareous microfossils were found only in the Holocene to mid-Pleistocene of the central Arctic Ocean during IODP Expedition 302 (Expedition 302 Scientists, 2006). The North and Norwegian Seas have been the subject of various biostratigraphic studies through the petroleum industry and scientific ocean drilling. A series of foraminifera zonation schemes exist for this region, most notably those of King (1989), Gradstein and Backstrom (1996), Laursen and Kristoffersen (1999), and Anthonissen (2009, 2012). Calibration of the utilized biohorizons in these schemes has generally improved over the years, although the challenges of diachroneity at high latitudes, due to both climate gradients as well as local basinal tectonic processes affecting bathymetry, remain. The integrated foraminifera, bolboformid, dinocyst, and diatom zonations defined from IODP and industry boreholes through the North and Nordic Seas of Anthonissen (2009, 2012) provide the most up-to-date biostratigraphic frameworks for the northeastern North Atlantic for the Pliocene and Miocene. ODP Leg 105 Site 645 on the southwestern side of Baffin Bay (70°N) is the nearest drilled site to Expedition 400 targets. Foraminifera studies at Site 645 found planktonic foraminifera-bearing sediments in the Pleistocene, but the Pliocene and Miocene were barren (Aksu and Kaminski, 1989; Kaminski et al., 1989). Likewise, Expedition 400 found only a few horizons containing planktonic foraminifera; thus, a minimal set of bioevents could be used. Shipboard observations allowed only a skeletal foraminifera biostratigraphic framework, involving sparse, tentatively calibrated planktonic and benthic events and broad, informal benthic assemblage zones inspired by Kaminski et al. (1989) (Figure F8).

3.1.2. Preparation and examination methods

Planktonic foraminifera were examined from core catcher samples, selected samples taken from split cores, and mudline samples from the top of selected holes. Sample volumes between 5 and 20 cm3 were washed over 63 µm sieves. Before sieving, samples were agitated in deionized water on a shaker table in Erlenmeyer flasks to aid clay disaggregation. Harder, more lithified samples were mechanically fractured before agitation using a mortar and pestle and then soaked in solutions of Borax and sometimes Liquinox while they were agitated on the shaker table. Empty sieves were soaked in methylene blue and cleaned in an ultrasonic bath between samples to identify sieve contaminants and minimize cross contamination between samples. Dried residues (>63 µm) were transferred to labeled glass vials. All or parts of the prepared sand residues were examined on metal picking trays using a Zeiss Discovery V8 stereomicroscope. Because the >63 µm residues are so variable in their terrigenous and other fossil contents, a representative view of the picking tray was commonly photographed using the QImaging Image Capture system coupled to the Zeiss light microscope (images uploaded to the LIMS database). These images are included with broader descriptions of sand fractions, including qualitative observations on the clast composition, size, shape, sorting, and other fossil remains.

To aid species identification, scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging was carried out for selected samples. This involved choosing candidate specimens, mounting them on a steel stub, and then applying a gold coating using a Leica EM ACE200 sputter coater. The specimens were imaged using a Hitachi TM3000 benchtop SEM. Routinely, whole specimen images were taken followed by close-ups of the apertural region or test wall to document wall textures and preservation quality.

Apart from planktonic foraminifera, the following particle categories were recorded: siliceous plankton; spicules; quartz; rock fragments; glauconite; pyrite; organic material (plant and wood fragments); volcanic ash; icthyoliths (including fish teeth, scales, etc.); and other fossiliferous materials, such as echinoid spines, mollusk fragments, and bryozoans. Planktonic foraminifera taxonomy follows Brummer and Kučera (2022) for the Pleistocene, with perspectives on morphotypes of N. pachyderma from El Bani Altuna et al. (2018) and Wade et al. (2018) for the Oligocene, with support from Mikrotax (https://www.mikrotax.org/pforams/). In practice, we tended to sieve samples into 63–125 µm and >125 µm fractions for our standard microscope observations. However, because of the low numbers of foraminifera encountered, abundances are pooled and reported as the relative numbers of specimens in the dried sample in the >63 µm fraction. The following abundance categories relative to total sediment particles were visually estimated:

- D = dominant (>50% of sediment particles).

- C = common (5%–50% of sediment particles).

- R = rare (<5% of sediment particles).

- Tr = trace (few individuals).

- B = barren.

Planktonic foraminifera preservation as viewed under the light microscope was recorded as follows:

- E = excellent, with most specimens having a glassy appearance indicating very little recrystallization and very little evidence of overgrowth or dissolution, as well as little abrasion.

- VG = very good, with some specimens showing minor evidence of diagenetic overgrowth, dissolution, or abrasion; recrystallization may or may not have occurred.

- G = good, with some specimens showing signs of significant overgrowth, dissolution, or abrasion and possibly some infilling with cement or indurated sediment.

- M = moderate, with most specimens showing evidence of overgrowth, dissolution, and abrasion; tests are generally infilled with cement or indurated sediment obscuring apertures.

- P = poor, with substantial diagenetic overgrowth, dissolution, and abrasion; foraminifera can be fragmented and difficult to identify because of major overgrowth and/or dissolution.

Planktonic foraminifera fragmentation as viewed under the light microscope was recorded as follows:

Where N. pachyderma was encountered, coiling ratios were utilized to investigate whether populations contained only N. pachyderma (a left:right coiling ratio of 5%:95% is expected) or a combination of N. pachyderma and Neogloboquadrina incompta (>5% right coiling is expected) (Darling et al., 2006).

3.2. Benthic foraminifera

No dedicated benthic foraminifera biostratigrapher sailed as a part of the Expedition 400 scientific party. However, the relative abundance of benthic species, including calcareous versus agglutinated species in the >63 µm size fractions, was routinely recorded and the presence of key marker species was noted. We anticipated several calcareous benthic foraminifera biostratigraphic markers in the sediments acquired during Expedition 400 (Figure F8). Seidenkrantz (1995) erected a new species, Cassidulina neoteretis, from its presumed direct ancestor, Cassidulina teretis Tappan (1951), on the basis of slight morphological changes (especially to the apertural plate) and differences in the species distributions. The LO of C. teretis Tappan (1951) has been placed between ~2.3 and 0.7 Ma in the North Atlantic and the Nordic Seas (Seidenkrantz, 1995). These species have been found commingled until the late Pleistocene in the Arctic Ocean (Lazar et al., 2016), suggesting that extinction of C. teretis was time transgressive (Cage et al., 2021). C. neoteretis is a common modern species in the Arctic Ocean and the northern North Atlantic, particularly around the Greenland margin, in areas occupied by chilled Atlantic water (c.f. Cage et al., 2021), making it important for paleoceanographic reconstructions in Baffin Bay and one of the few markers featured in our coarse biostratigraphic scheme (Figure F8).

Benthic foraminifera in the Pliocene/Pleistocene Clyde Foreland Formation of eastern Baffin Island (Feyling-Hanssen, 1976) and the Kap København Formation (Feyling-Hanssen, 1990; Funder et al., 2001) of northern Greenland contain taxa that do not occur in Baffin Bay today. In particular, Cibicides grossus Ten Dam and Reinhold, 1941, and Nonion tallahattensis Bandy, 1949, are taxa that were found only in sections considered to be of Pliocene age by Feyling-Hanssen in the Clyde Foreland Formation; they do not occur in the Arctic today. Recent attempts to use amino acid racemization and cosmogenic radionuclide dating of the Clyde Foreland Formation confirm latest Pliocene to early Pleistocene ages for the oldest units (Refsnider et al., 2013), reinforcing their utility for Expedition 400 biostratigraphy. The taxonomy of recognized benthic species follows Feyling-Hanssen (1976, 1990), Kaminski et al. (1989), and Cage et al. (2021). Although, as found at ODP Site 645 (Kaminski et al., 1989), agglutinated benthic species are present in Expedition 400 cores, we have not attempted to use agglutinated benthic species for biostratigraphic purposes. We anticipate that doing so, especially for Site U1607, could be a fruitful path for future work.

Benthic foraminifera abundance based on observations of the dried sample in the >63 µm fraction was recorded using the following scheme:

- D = dominant (>50% of the foraminifera assemblage).

- C = common (5%–50% of the foraminifera assemblage).

- R = rare (<5% of the foraminifera assemblage).

- Tr = trace (few individuals).

- B = barren.

The relative abundance of calcareous and agglutinated benthic species, respectively, were recorded using the following scheme:

- D = dominant (>50% of the foraminifera assemblage).

- C = common (5%–50% of the foraminifera assemblage).

- R = rare (<5% of the foraminifera assemblage).

- Tr = trace (few individuals).

- B = barren.

3.3. Diatoms

3.3.1. Taxonomy and zonal scheme

The Neogene and Quaternary diatom biostratigraphy principally follows the previous works carried out in the North Atlantic by Baldauf (1984, 1987) (Deep Sea Drilling Project [DSDP] Legs 81 and 94), Koç and Scherer (1996) (ODP Leg 151), and Koç et al. (1999) (ODP Leg 162). The North Pacific diatom zonation, developed by Barron (1985) (DSDP Leg 85), Akiba (1986) (DSDP Leg 87), Barron and Gladenkov (1995) (ODP Leg 145), and Yanagisawa and Akiba (1998), was also used when diatom species from the North Pacific were encountered. Although the Oligocene and Eocene diatom zonation from the Norwegian Sea Cenozoic diatom biostratigraphy by Schrader and Fenner (1976) (DSDP Leg 38), Dzinoridze et al. (1978) (DSDP Leg 38), and Fenner (1985) and Scherer and Koç (1996) (ODP Leg 151) was not applied due to the lack of specific diatom biostratigraphic markers, diatom descriptions and photomicrographs therein were used to identify certain species. Furthermore, diatom resting spores are an integral part of diatom biostratigraphy (e.g., Suto, 2005). Therefore, the North Atlantic biostratigraphic schemes of diatom resting spore genera (e.g., Goniothecium, Dicladia, Monocladia, and Syndendrium) were also employed to provide age control (Suto, 2005; Suto et al., 2008). Diatom biostratigraphic age constraints were also obtained from data sets from the Janus database (http://www-odp.tamu.edu/database) and then calibrated to the 2020 geomagnetic polarity timescale (GPTS2020; Gradstein et al., 2020) using the Neptune database (https://www.museumfuernaturkunde.berlin/en/science/nsb-database) (Figure F8). The recognized diatom biohorizons involve the FOs and LOs of key species.

Diatoms were identified to species level where possible. Key stratigraphic markers were identified according to previous work by Schrader and Fenner (1976), Baldauf (1984), Akiba (1986), Monjanel and Baldauf (1989), Baldauf and Monjanel (1989), Koç and Scherer (1996), and Koç et al. (1999).

Although the shipboard micropaleontology work mainly focuses on the identification of biostratigraphically useful events, additional biosiliceous microfossil groups of specific environmental indications were also identified and recorded from the same sample. This was done for additional age control and included sea ice and marine diatoms, freshwater diatoms, silicoflagellates, ebridians, and siliceous spicules of endoskeletal dinoflagellates. These microfossils were identified based on previous studies in the northern high latitudes by Sancetta (1982), Koç Karpuz and Schrader (1990), Pearce et al. (2014), Tsoy and Obrezkova (2017), and Oksman et al. (2019).

3.3.2. Preparation and analysis methods

Smear slides from the core catcher samples were examined on a routine basis for stratigraphic markers and paleoenvironmentally sensitive taxa. A toothpick sample of sediment was placed on a 22 mm × 40 mm coverslip and wetted with deionized water and a small amount of regular soap to break the surface tension and ensure a relatively homogeneous spread of sediment over the coverslip. The coverslips were allowed to dry on a hot plate. Once dried, a few drops of Norland Optical Adhesive Number 61 (refractive index = 1.56) were added and covered with coverslips. The microscope slides were then placed under the ultraviolet lamp and cured for ~10 min.

For samples of low diatom concentration but with critical stratigraphic and paleoenvironmental implications, slides were prepared from core catcher and section half samples using the following procedures. A ~2 cm3 sediment sample was placed in a 250 mL beaker with 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and sodium borate (Borax) to remove organic material and to disaggregate clay-sized sediments. Carbonate was generally rare in most samples; thus, hydrochloric acid (HCl) was not used. When the reaction was complete, the sample was diluted with distilled water until the residue was neutralized. The diatoms were then concentrated by using a 10 µm mesh sieve. A few aliquots of the sieved sample residue were evenly dropped on a 22 mm × 40 mm coverslip and mounted with Norland Optical Adhesive Number 61 (refractive index = 1.56) under the ultraviolet lamp. The sieved slide method may bias the total diatom abundance, but it is practical to observe diatoms in low concentration samples.

Samples prepared for diatom analysis were examined using a Zeiss Axioskop transmitted light microscope. For photomicrographs, a SPOT Flex 64 Mp digital camera was used. A Hitachi TM3000 tabletop SEM was used for further taxonomic assessments when needed. Qualitative siliceous microfossil group abundances were determined from smear slides using 630× magnification. Additionally, samples were routinely examined under 1000× magnification for detailed taxonomic observations. Care was taken to ensure smear slides were prepared with similar amounts of sediments to produce consistent abundance estimates.

For each sample, the total abundance of diatoms was qualitatively estimated by light microscopic observations with the examination of five random FOVs, following the classification listed below:

- M = mass abundance (>60% diatoms).

- A = abundant (>20% diatoms).

- C = common (10%–20% diatoms).