Hall, I.R., Hemming, S.R., LeVay, L.J., and the Expedition 361 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 361

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.361.204.2026

Data report: systematic taxonomy, morphology, and distribution of Late Neogene–Quaternary planktic foraminifera from the Agulhas Current region, International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 361, Hole U1474A1

Vikram Pratap Singh,2 Rahul Dwivedi,2 and Shivani Pathak2

1 Singh, V.P., Dwivedi, R., and Pathak, S., 2026. Data report: systematic taxonomy, morphology, and distribution of Late Neogene–Quaternary planktic foraminifera from the Agulhas Current region, International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 361, Hole U1474A. In Hall, I.R., Hemming, S.R., LeVay, L.J., and the Expedition 361 Scientists, South African Climates (Agulhas LGM Density Profile). Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 361: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.361.204.2026

2 Department of Geology, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, India. Correspondence author: vikram.singh@igntu.ac.in

Abstract

International Ocean Discovery Program Hole U1474A, drilled during Expedition 361 in the southwestern Indian Ocean, offers a high-quality archive for reconstructing Agulhas Current variability. The site yielded 104% core recovery over 256.11 m, spanning from the Late Miocene to recent. The sediments are exceptionally well preserved and contain a diverse planktic foraminiferal assemblage, including tropical, subtropical, temperate, and subpolar forms.

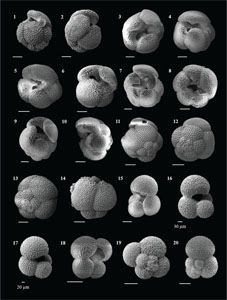

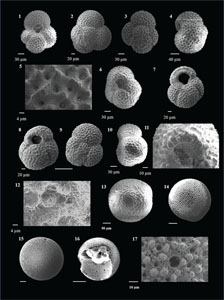

This study presents a detailed morphological and taxonomic analysis of Late Neogene–Quaternary planktic foraminifera from Hole U1474A, supported by scanning electron micrographs. Accurate species identification is essential for understanding mid-latitude paleoceanographic events and diachrony. The specimens exhibit minimal dissolution, with well-preserved wall textures and visible spines. A total of 63 species were identified, representing tropical to temperate faunas. Dominant genera include Globigerinoides, Globoconella, Globigerinita, and Neogloboquadrina. A semiquantitative distribution of these forms is also provided to support further biostratigraphic and paleoenvironmental reconstructions in the Agulhas Current region.

1. Introduction

The planktic foraminifera, which are excellent index fossils, form the backbone of the Cenozoic biostratigraphic and paleoceanographic studies. Because of their passive mode of life, they are susceptible to stresses caused by variations in water mass properties like temperature, salinity, and nutrient conditions. The response to changes in the ambient water mass conditions is recorded in the test of the planktic foraminifera, which is exploited for paleoceanographic and paleoclimatic studies. It therefore becomes prudent that these sensitive proxies be precisely identified to be used for paleoceanographic and paleoclimatic interpretations.

With the development of scanning electron microscopy (SEM), there has been a tremendous development in the taxonomic studies of planktic foraminifera over the last few decades. Several studies have been conducted on the taxonomic refinements of the Neogene–Quaternary planktic foraminifera (Lamb and Beard, 1972; Stainforth et al., 1975; Saito, 1977; Steineck and Fleisher, 1978; Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Bolli and Saunders, 1985; Jenkins, 1985; Cifelli and Scott, 1986; Hemleben et al., 1989; Hilbrecht, 1996; Fox and Wade, 2013; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Lam and Leckie, 2020a, 2020b; Brummer and Kučera, 2022). The integration of taxonomic studies on fossilized tests and molecular genetic studies on extant species of planktic foraminifera (e.g., Darling et al., 2006; André et al., 2013; Spezzaferri et al., 2015; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Poole and Wade, 2019, and others) has opened new avenues to ascertain the affinity of various morphotypes.

The growing number of works and literature on the taxonomic revision of planktic foraminifera has sparked a debate on the selection of the appropriate nomenclature and the generic and specific assignment of planktic foraminifera. It warrants the development of a precise concept of the taxonomic identification of planktic foraminifera for use in studies pertaining to marine geology.

Another important characteristic of planktic foraminifera is latitudinal provincialism (Bé and Tolderlund, 1971), which controls their distribution according to the latitudes. It is an essential aspect of planktic foraminiferal research that assists in paleoceanographic and paleoclimatic reconstructions.

This work aims to present a detailed SEM examination of well-preserved planktic foraminiferal specimens from Hole U1474A, which helps to determine the taxonomy and morphological variability of 63 Late Miocene–recent species.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Location and modern oceanography of the study area

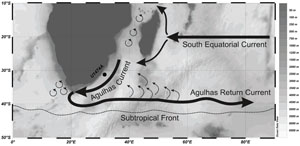

International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Hole U1474A was drilled during Expedition 361 in the northernmost part of the Natal Valley (31°13.00′S, 31°32.71′E) at a water depth of 3045 meters below sea level (mbsl), which is well above the carbonate compensation depth, resulting in good preservation of biogenic material (Figure F1; Hall et al., 2017). This site is located in the path of the Agulhas Current. It has the potential to record the variation in faunal assemblages due to the changes in the intensity of the current. The Agulhas Current is the largest western boundary current (Simon et al., 2013) that affects the surface dynamics in the Indian Ocean. The warm water of the Agulhas Current transported to the Atlantic Ocean via the Indo-Atlantic gateway by the Agulhas leakage in the form of eddies and rings (Lutjeharms, 2006) has a significant impact on the returning arm of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. After 40°S, the Agulhas Current retroflects and returns to the Indian Ocean as the Agulhas Return Current, which flows along the Subtropical Front (Lutjeharms, 2009). The Subtropical Front is a hydrodynamic front that is the "gatekeeper" south of Africa (Graham and De Boer, 2013). It changes its position with variation in the climate, with a more northward position indicative of glacial climate and a southward position marking a return to warmer conditions (Peeters et al., 2004; Caley et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2023). The northward position of the Subtropical Front allows the ingression of cold temperate waters into the relatively warmer subtropical latitude, thereby causing a shift in the ecotones and changing the faunal assemblages to be dominated by characteristic cold-water forms. In the present work, we observed several episodes of significant rise in the relative abundance of cold-water forms, dominated by the genus Globoconella. Thus, the variation in the planktic foraminiferal assemblage is an important proxy for paleoceanographic reconstruction.

The terrigenous part of the sediment core recovered from Hole U1474A is clay dominated, and the biogenic fraction of the sediment is composed primarily of calcareous nannofossils, foraminifera, and siliceous sponge spicules, which makes it foram-nanno ooze (Hall et al., 2017).

The total length of the cored section is 254.1 m, with core recovery of 104% in 29 advanced piston cores (Hall et al., 2017). The dominant lithology consists of yellow to greenish gray clay that contains foraminifera and nannofossils, with occasional occurrences of sand and turbidite lenses. Total biogenic carbonate concentration is estimated to be around 39% (Hall et al., 2017). Of the total cored length, we used 233.4 m, comprising 25 cores for the present work (361-U1474A-1H through 25H), from which the sediments were sampled at an interval of 30 cm. The volume of each sample was 10 cm3, and the approximate temporal gap between the two samples was calculated to be 6–8 ky (Singh et al., 2023). A total of 710 samples, spanning Late Miocene to recent, were analyzed for planktic foraminiferal assemblages to establish Late Neogene–Quaternary biostratigraphy and paleoceanography in the Agulhas Current region.

2.2. Sample processing using the wet-sieving technique

In this study, planktic foraminiferal assemblages from Hole U1474A core samples obtained from Kochi Core Center (Japan) were studied. A detailed biostratigraphy was established (Singh et al., 2025) for the 710 samples at 30 cm sampling intervals, spanning the last ~7 My. Additionally, planktic foraminiferal census count and stable isotope data for these samples were generated for the Late Neogene–Quaternary paleoceanographic and paleoclimatic reconstruction.

The samples were oven-dried overnight at approximately 60°C and weighed. After drying, they were dissolved in 1 L of alkaline solution containing 1 g sodium hexametaphosphate (NaPO3)6 and 5 g sodium hydroxide (NaOH). To assist the disintegration of the clay, occasionally 10 mL H2O2 was added. The solution was then subjected to an ultrasonic bath for 2 min to enhance disintegration. After this treatment, the samples were thoroughly washed with tap water over sieves of two sizes: ≥150 µm and ≥100 µm. The samples were left to dry at room temperature overnight. The dried residue of the two sizes was carefully transferred into three tubes that corresponded to 150 µm, 100 µm, and the base for mud collection for each sample.

2.3. Age model for Hole U1474A

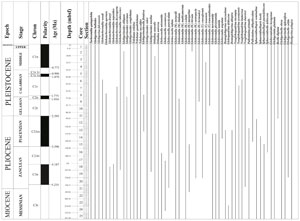

A detailed paleomagnetic record was obtained from the shipboard investigation (Hall et al., 2017) for Hole U1474A. Table T1 lists the paleomagnetic events recorded for Hole U1474A along with their absolute ages, as derived from Ogg (2020).

This record was used to calculate the rate of sedimentation and estimate the approximate age of the samples under investigation, assuming a uniform rate of sedimentation. The rate of sedimentation was determined by dividing the depth of the core by the corresponding paleomagnetic age and was then multiplied by the depth of the samples to estimate their ages.

3. Results

3.1. Foraminifera

The planktic foraminiferal assemblages from Hole U1474A spanning Late Neogene–Quaternary were analyzed for the taxonomic studies. We encountered 63 species belonging to 21 genera that were prominent in their occurrence in Hole U1474A. The list of the genera and species is provided in Table T2.

The processed samples were spread in a picking tray and were studied under the Zeiss Discovery V.8 Stereozoom microscope with camera facility. The planktic foraminifera were identified to the species level following the taxonomic work of Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Huber et al. (2016), and Lam and Leckie (2020a).

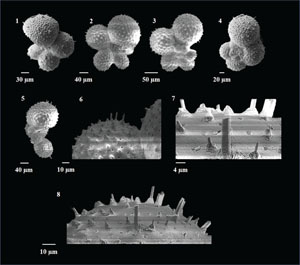

The details of surface ultrastructure, pores, spines, keel, and so on were studied using a Carl Zeiss EVO-18 scanning electron microscope at the Department of Geology at Banaras Hindu University (India). The specimens were mounted on stubs using carbon tape and were coated with gold-palladium alloy before being loaded in the SEM.

3.2. Diversity

The diversity of foraminiferal assemblages in Hole U1474A is quite high. We identified a total of 63 species from Late Miocene to recent comprising a mixture of warm tropical–subtropical and cool temperate–subpolar forms. Although the warm-water dwellers were dominant forms in the entire core, the Quaternary section showed an unprecedented rise in the cold-water species, which occasionally comprised more than half of the entire assemblage of planktic foraminifera.

3.3. Biostratigraphy

Hall et al. (2017) conducted low-resolution biostratigraphy aboard ship for Hole U1474A using core catcher samples supplemented with an additional one sample per section for the entire core. Although this study was preliminary and used Wade et al. (2011) as the reference for the ages, we revised the entire shipboard range charts and updated the biostratigraphy following Kennett (1973), Jenkins and Srinivasan (1986), and Lam and Leckie (2020b). The detailed biostratigraphy is presented in Singh et al. (2025). The stratigraphic range of the important planktic foraminiferal species is given in Figure F2.

3.4. Systematic paleontology

The systematic descriptions of the encountered species follow the existing understanding of Late Neogene–Quaternary planktic foraminiferal taxonomy as well as new taxonomic concepts developed and revised over the years (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Bolli and Saunders, 1985, Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Lam and Leckie, 2020a; Brummer and Kučera, 2022).

In this study, we have documented as many species as possible encountered from the Agulhas Current region to prepare a catalogue of the tropical and temperate forms from the mid-latitudes in the southwest Indian Ocean. We have elaborated the significant morphological features for each species to help with precise identification in each Remarks section. Although we tried to incorporate the minute and subtle observations used for identification, we do not claim that these are the complete descriptions of any species. These observations may be used along with the relevant literature for taxonomic identifications (e.g., Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Bolli and Saunders, 1985; Cifelli and Scott, 1986; Scott et al., 1990; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Wade et al. 2018; Lam and Leckie, 2020a; Brummer and Kučera, 2022). Along with the published work, we also cite the website https://www.mikrotax.org/pforams (Huber et al., 2016) for latest concepts, SEM images, and references.

The species that were excluded from the list are those with extremely rare occurrences in Hole U1474A. The basionyms, synonyms (if any), and original references for each species are included in the notes that follow. SEM images of specimens are designed to capture the range of morphological variability within a species concept.

The plates are arranged by the family in which the species occur, within which the taxa are listed alphabetically by genus and species name. The images of various morphotypes within a species are arranged in the stratigraphic order of occurrence with the core.

Order FORAMINIFERIDA d'Orbigny 1826

Superfamily GLOBIGERINOIDEA Carpenter, Parker and Jones 1862

Family CANDEINIDAE Cushman 1927

Type species Candeina nitida d'Orbigny 1839

Candeina nitida (d'Orbigny 1839)

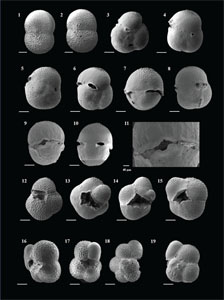

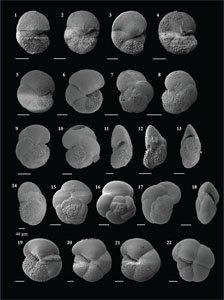

(Plate P1, figures 1–3)

Synonym: Candeina milletti Dolfus (1905), Candeina nitida praenitida Blow (1969)

Type species: Candeina nitida d'Orbigny, 1839

References: d'Orbigny (1839), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Loeblich and Tappan (1994), Norris (1998), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Meilland et al. (2022), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-23H-7, 54–56 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. C. nitida is an extant species characterized by a high trochospiral compact test. The final whorl has three chambers. The surface is smooth and microperforate. The characteristic feature of C. nitida is the presence of sutural supplementary apertures, each of which is bordered by a rim.

This thermocline dweller (Lessa, 2020) is found in tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). This species is rare and shows irregular occurrence in Hole U1474A.

Family GLOBIGERINIDAE Carpenter, Parker and Jones 1862

Genus Beella Banner and Blow 1960

Type species Globigerina digitata Brady 1879

Beella praedigitata (Parker 1967)

(Plate P1, figures 4–8)

Basionym: Globigerina praedigitata

Synonym: Beella megastoma Earland (1934)

Type species: Beella praedigitata (Parker, 1967)

References: Parker (1967), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Lam and Leckie (2020a).

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-23H-7, 54–56 cm, to 4H-1, 10–12 cm

Remarks. B. praedigitata has a low trochospiral test with four to five inflated chambers in the final whorl. The surface is spinose and smooth (Aze et al., 2011), consisting of circular pores and tubercles representing spine bases (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983).

It evolved from G. bulloides in the Late Miocene (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983) and evolved into B. digitata by giving rise to radially elongate chambers (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Lam and Leckie, 2020a). B. praedigitata is a thermocline dweller (Aze et al., 2011) extending from tropical to temperate latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It is extremely rare in Hole U1474A.

(Plate P1, figures 9–13)

Basionym: Globigerina digitata

Synonyms: Beella chathamensis McCulloch (1977), Beella guadalupensis McCulloch (1977), Hastigerina frailensis McCulloch (1977).

Type species: Beella digitata Brady, 1879

References: Brady (1879), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Vella (1975), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022).

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-11H-7, 35–37 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. B. digitata differs from B. praedigitata in having radially elongate chambers. It has a high trochospiral test, with four to five radially elongated chambers in the final whorl. The wall is spinose and irregularly cancellate (Aze et al., 2011).

B. digitata is a thermocline dweller (Aze et al., 2011) extending from tropical to temperate latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It is a regularly occurring species in the Quaternary samples but very low in abundance.

Genus Dentoglobigerina Blow 1979

Type species Globigerina galavisi Bermúdez 1961

Dentoglobigerina venezuelana (Hedberg 1937)

(Plate P1, figures 14–17)

Basionym: Globigerina venezuelana

Synonym: Globoquadrina venezuelana, Globoquadrina conglomerata (?)

Type species: Dentoglobigerina venezuelana Hedberg, 1937

References: Hedberg (1937), Postuma (1971), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Wade et al. (2018), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 13H-4, 77–79 cm

Remarks. D. venezuelana is characterized by a very large test with a wide umbilicus. There are four reniform chambers in the final whorl, and the wall is spinose to cancellate (Wade et al., 2018). The test is sometimes pustulose on the umbilical shoulders and may also show the presence of umbilical teeth, thereby closely resembling Dentoglobigerina altispira.

There has been considerable debate over the generic affinity of this species. Kennett and Srinivasan (1983) assigned it to Globoquadrina, which was also accepted by Bolli and Saunders (1985) and Aze et al. (2011). Later, Wade et al. (2018) determined that this species was spinose and thus transferred it to Dentoglobigerina. Lam and Leckie (2020a) have also included it in Dentoglobigerina. Another form, Globoquadrina conglomerata Schwager (1866) was considered a distinct species by Saito et al. (1981), Hemleben et al. (1989), and Lam and Leckie (2020a). Lam and Leckie (2020a) suggest that it is the extant form and a separate species that differs morphologically from D. venezuelana. Banner and Blow (1960), Parker (1962), and later Wade et al. (2018) considered G. conglomerata a synonym of D. venezuelana. Brummer and Kučera (2022) chose to retain venezuelana in Globoquadrina based on the genetic data by Morard et al. (2019), which does not show any affinity to the spinose clade. This thermocline dweller is globally found in low and mid latitudes (Wade et al., 2018). In Hole U1474A, it is a commonly occurring species during the Late Pliocene, although the abundance is quite low.

Dentoglobigerina altispira (Cushman and Jarvis 1936)

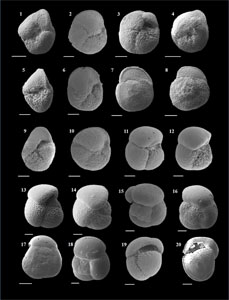

(Plate P2, figures 1–14)

Basionym: Globigerina altispira

Synonym: Dentoglobigerina altispira altispira, Dentoglobigerina altispira conica

Type species: Dentoglobigerina altispira Cushman and Jarvis, 1936

References: Cushman and Jarvis (1936), Postuma (1971), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Fox and Wade (2013), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 13H-4, 77–79 cm

Remarks. D. altispira is characterized by large, high trochospiral tests with four to five chambers in the final whorl. The chambers are appressed toward the umbilicus. The umbilicus is wide open and deep and shows umbilical teeth. The surface is cancellate with pores in pore pits.

Another species, D. altispira globosa Bolli (1957), differs from D. altispira in having five to six chambers in the final whorl and a low trochospiral test (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It has not been differentiated in this work owing to the scope of the objectives.

D. altispira is a shallow mixed-layer dweller (Srinivasan and Sinha, 2000; Aze et al., 2011) and is commonly found in tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It is a regularly occurring species in Hole U1474A in samples spanning the Pliocene and shows moderately high abundance, occasionally reaching up to 6%.

Genus Globigerina d'Orbigny 1826

Type species Globigerina bulloides d'Orbigny 1826

Globigerina bulloides (d'Orbigny 1826)

(Plate P2, figures 15–20; Plate P3, figures 1–4)

Basionym: Globigerina bulloides

Type species: Globigerina bulloides d'Orbigny 1826

References: d'Orbigny (1826), Schwager (1866), Banner and Blow (1960), Lamb and Beard (1972), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Jenkins (1985), Shrivastav et al. (2016), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. bulloides is a commonly occurring species in the eutrophic waters along the Equator, temperate regions, and in the-low latitude upwelling zones (Bé, 1977; Duplessy et al., 1981; Naidu et al., 1992; Naidu and Malmgren, 1996; Sinha et al., 2006; Shrivastav et al., 2016; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Brummer and Kučera, 2022). It is characterized by a low trochospiral test with a characteristic G. bulloides-type wall texture. This wall texture is characterized by a hispid surface (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983), which has thin and round spines, and an irregular pore pattern with a narrow space between pores (Hemleben and Olsson, 2006). The overall test morphology closely resembles quite a few other species like Globigerinella calida, Globigerinella obesa, Globigerina falconensis, and sometimes vaguely Globigerinita glutinata (without bulla). However, the umbilical aperture in G. bulloides, which is slightly eccentric, distinguishes it from G. calida, which has the aperture facing either left or right side (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017); G. obesa differs from G. bulloides by its extraumbilical aperture (Shrivastav et al., 2016); the absence of apertural rim or lip separates it from G. falconensis (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983); and the wide, high-arch aperture and surface ultrastructure distinguish G. bulloides from G. glutinata (Darling and Wade, 2008). The test of G. bulloides frequently exhibits the presence of a kummerform final chamber.

The considerable variability in the shape and number of chambers in G. bulloides has led to great confusion in taxonomic identification (Lamb and Beard, 1972) and the erection of several species by other authors, for example, Globigerina bermudezi Seiglie 1963, Globigerina cariacoensis Rögl and Bolli 1973, Globigerina megastoma Earland 1934, Globigerina quadrilatera Galloway and Wissler 1927, and Globigerina riveroae Bolli and Bermúdez 1965, all of which are morphotypes and closely resemble G. bulloides (Shrivastav et al., 2016). Kennett and Srinivasan (1983) dubbed these morphotypes phenotypic variants of G. bulloides.

The molecular genetic studies by various authors have distinguished 14 genetic types of G. bulloides (Darling et al., 2000; Darling and Wade, 2008; André et al., 2013; Morard et al., 2013; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). Later, André et al. (2014) suggested that only seven genotypes of G. bulloides qualify for a species status. Seears et al. (2012) showed bipolar distribution of a few genotypes of G. bulloides, suggesting a gene flow across the tropics, as suggested earlier by Darling et al. (2000). This species has attracted significant attention for its correct taxonomic identification owing to its importance as proxy for upwelling episodes in the low and mid latitudes.

This species is a temperate-latitude, mixed-layer dweller (Bé and Tolderlund, 1971) and thrives in high nutrient conditions, indicative of upwelling in lower latitudes (Thiede, 1975; Bé and Hutson, 1977; Naidu and Malmgren, 1996; Seears et al., 2012; Shrivastav et al., 2016; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017) and seasonally enhanced primary production at mid and high latitudes (Bé and Tolderlund, 1971; Ottens, 1992; Chapman, 2010; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017).

In the present study, this species is encountered throughout the Late Neogene–Quaternary span, with significantly high abundance in several samples representing episodes of enhanced productivity in Hole U1474A.

Globigerina falconensis (Blow 1959)

(Plate P3, figures 5–10)

Basionym: Globigerina falconensis

Synonym: Globorotalia (Turborotalia) palpebra Brönnimann and Resig (1971)

Type species: Globigerina falconensis Blow, 1959

References: Blow (1959), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Jenkins (1985), Iaccarino (1985), Shrivastav et al. (2016), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022), Fabbrini et al. (2023)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. The test of G. falconensis closely resembles G. bulloides in its appearance, with G. bulloides-type wall structure, globular chambers, and the slightly eccentric umbilical aperture. The main difference lies in the presence of a distinct apertural lip. Although the apertural area is usually smaller than G. bulloides (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017), it is not very distinct unless the test is morphometrically analyzed. Kennett and Srinivasan (1983) mentioned that the final chamber of G. falconensis is distinctly smaller than the penultimate chamber, but this feature was not observed in all the specimens. There were several forms that did not adhere to this observation by Kennett and Srinivasan (1983). Thus, the presence of lip in the last chamber wall becomes an essential criterion for its distinction.

Fabbrini et al. (2023), on the basis of morphometric analysis, reported the presence of interpore ridges in G. falconensis and opined that the wall structure was more pseudocancellate than G. bulloides-type. Fabbrini et al. (2023) described a new morphotype, Globigerina neofalconensis, distinguished from G. falconensis by its more lobate profile, more loosely coiled test, and wider umbilicus.

In the present study, all morphotypes with lobate outline, globular chambers, G. bulloides-type wall, and aperture with a prominent lip have been identified as G. falconensis. It is a commonly occurring species in Hole U1474A, but its abundance has mostly stayed within 5%.

Genus Globigerinella Cushman 1927

Type species Globigerina aequilateralis Brady 1879

Globigerinella calida (Parker 1962)

(Plate P3, figures 11–17)

Synonym: Globigerina calida calida, Bolliella calida calida

Type species: Globigerina calida Parker, 1962

References: Parker (1962), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Chaproniere et al. (1994), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-19H-7, 47–49 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. calida has a smaller, less planispiral test, which separates it from G. siphonifera, and the radially elongated chambers in the final whorl distinguish it from G. obesa (Brummer and Kučera, 2022). It has a G. bulloides-type wall, characteristic of this lineage.

This thermocline dweller is commonly found in tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Aze et al., 2011). In Hole U1474A, G. calida occurs regularly with higher abundance in Quaternary samples than Pliocene samples.

Globigerinella obesa (Bolli 1957)

(Plate P4, figures 1–9)

Synonym: Globigerina praebulloides Blow (1959)

Type species: Globigerinella obesa Bolli, 1957

References: Bolli (1957), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Spezzaferri et al. (2018), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 32–34 cm

Remarks. G. obesa is characterized by a strongly lobulate test with four chambers in the final whorl. The surface is densely perforated and spinose with spine bases coalescing into regular ridges (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983).

G. obesa very closely resembles G. bulloides, but it can be distinguished on the basis of flat spiral side and extraumbilical aperture (Lam and Leckie, 2020a). It is commonly found in low to mid latitudes (Spezzaferri et al., 2018). In Hole U1474A, it is extremely low in abundance.

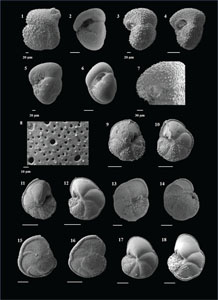

Globigerinella siphonifera (d'Orbigny 1839)

(Plate P4, figures 10–14)

Basionym: Globigerina siphonifera

Synonym: Globigerina aequilateralis Brady (1879), Globigerina aequilateralis involuta Cushman (1917), Hastigerina aequilateralis

References: d'Orbigny (1839), Brady (1879), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Pearson (1995), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. siphonifera is characterized by an irregular planispiral test. Five to six chambers are present in the final whorl. The surface is spinose with G. bulloides-type wall and rounded spines. The aperture is wide arch and extends from umbilicus to spiral side, without rim or lip.

G. siphonifera is a thermocline dweller, living in low to mid latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Aze et al., 2011). It occurs regularly in Hole U1474A in moderate abundance.

Genus Globigerinoides Cushman 1927

Type species Globigerina rubra d'Orbigny 1839

Globigerinoides conglobatus (Brady 1879)

(Plate P4, figures 15–18; Plate P5, figures 1–3)

Basionym: Globigerina conglobatus

Synonym: Globigerinoides carimanensis Bermúdez (1960)

Type species: Globigerinoides conglobatus Brady, 1879

References: Brady (1879), Banner and Blow (1960), Jenkins (1971), Kennett (1973), Fleisher (1974), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. conglobatus is characterized by its compact, large test with three to four flattened chambers, giving a subquadrate outline to the test. It can be distinguished by its tight coiling and an unusually flat final chamber. The test is often very thick and has a G. ruber-type wall. The surface has large pores, triangular spines and spine holes, which are often obscured by a thick calcite crust (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). The umbilicus is small, and the primary aperture varies from a low slit to a low arch centered on the previous chambers. The spiral side bears two or more sutural supplementary apertures. An interesting observation in the present work was a higher abundance of morphotypes with three chambers during the Late Miocene–Early Pliocene, whereas four-chambered forms dominated Late Pliocene–Quaternary. G. conglobatus is an extant species that prefers open ocean mixed-layer habitat (Aze et al., 2011) and extends from tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017) and is often transported by ocean currents to lower mid latitudes (Schmuker and Schiebel, 2002).

This species is found across Late Neogene–Quaternary and rarely exceeds 1.5% abundance in Hole U1474A.

Globigerinoides extremus (Bolli and Bermúdez 1965)

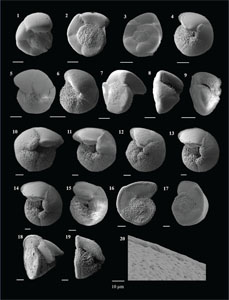

(Plate P5, figures 4–10)

Basionym: Globigerinoides obliquus extremus

Type species: Globigerinoides extremus Bolli and Bermúdez, 1965

References: Bolli and Bermúdez (1965), Postuma (1971), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 8H-6, 4–6 cm

Remarks. G. extremus evolved from G. obliquus by the development of laterally compressed four chambers in the final whorl and distinctly flattened final chamber (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Bolli and Saunders, 1985), resembling a beret (Lam and Leckie, 2020a). The surface is distinctly pitted, and has G. ruber/T. sacculifer-type wall. The surface exhibits tubercles with spine holes, which were formed when the spine was shed. The primary aperture is oblique in shape, umbilical, and there is one supplementary aperture opposite the primary one.

G. extremus extends from tropical to cool subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983), preferring open ocean mixed-layer habitat (Aze et al., 2011). It occurs in extremely low abundance in the upper part of the core compared to the lower part, where it is common to abundant.

Globigerinoides obliquus (Bolli 1957)

(Plate P5, figures 11–18)

Basionym: Globigerinoides obliqua

Type species: Globigerinoides obliqua Bolli (1957)

References: Bolli (1957), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Spezzaferri (1994), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Singh et al. (2021)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 2H-3, 52–54 cm

Remarks. G. obliquus shows a lobate test with four ovate chambers in the final whorl, and the last chamber is obliquely compressed. The surface is spinose, distinctly pitted and perforate, exhibiting G. ruber/T. sacculifer-type wall (Spezzaferri et al., 2018). The primary aperture is umbilical, high and wide arch. There is one supplementary aperture on the spiral side, opposite the primary aperture.

This cosmopolitan species occurs commonly at middle and high latitudes (Spezzaferri et al., 2018) and prefers mixed-layer habitat (Chaisson and Ravelo, 1997).

The lowest occurrence (LO) of G. obliquus is an important biostratigraphic event and has been assigned a mid-Pleistocene age by several authors (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Aze et al., 2011; Wade et al., 2011; Brummer and Kučera, 2022) and Late Pleistocene by others (Sinha and Singh, 2008, 2022; Lam and Leckie, 2020b; Kaushik et al., 2020). In the present study, the LO of this species was found in the samples of the Late Quaternary. In Hole U1474A, G. obliquus occurs in high abundance in the lower part of the core spanning the Pliocene, and the Quaternary section has extremely low abundance.

Globigerinoides ruber (d'Orbigny 1839)

(Plate P6, figures 1–10)

Type species: Globigerinoides ruber d'Orbigny (1839)

References: d'Orbigny (1839), Banner and Blow (1960), Postuma (1971), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Loeblich and Tappan (1994), Wang (2000), Numberger et al. (2009), Spezzaferri et al. (2015), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Jayan et al. (2021), Latas et al. (2023)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. ruber can be distinguished by a three-chambered, low to high trochospiral test with its primary and supplementary sutures symmetrically placed above the suture between the earlier chambers of the final whorl. The suture line seems to bisect the primary aperture. The surface is spinose with a G. ruber-type wall.

This species exhibits several morphotypes during its entire stratigraphic range, especially during the Quaternary, during which it shows a wide range of variation in the height of the spire and tightness of the test coiling (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). These variations led to the recognition of several taxa: forms with a high trochospiral test were named Globigerinoides pyramidalis (Van den Broeck, 1876), forms with tightly coiled tests were named Globigerinoides elongatus (d'Orbigny, 1826), and those with a compact test and smaller aperture were called Globigerinoides cyclostomus (Galloway and Wissler, 1927). All these forms were considered phenotypic variants by Kennett and Srinivasan (1983).

Two chromotypes of G. ruber were identified as phenotypes: a white variety, also referred to as G. ruber subspecies albus (Morard et al., 2019), and a pink variety, G. ruber subspecies ruber (d'Orbigny, 1839). The name of this species is actually derived from the pink color of its tests (Aurahs et al., 2009; Morard et al., 2019). The white variety was originally given the name G. ruber forma albus by Boltovskoy (1968) and was later differentiated into G. ruber sensu stricto (s.s.) and G. ruber sensu lato (s.l.) by Wang (2000) on the basis of their morphometry and stable isotopic compositions.

The white variety of G. ruber is extant in all the ocean basins and dominates in the tropical and subtropical water masses (Bé and Hamlin, 1967; Hemleben et al., 1989), and the pink variety of G. ruber became extinct in the Indian and Pacific Oceans during Late Pleistocene (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017) and preferred warmer habitats than white variants (Bé and Hamlin, 1967, Hemleben et al.1989). The LO of G. ruber (pink) is an important biostratigraphic event in the Indian and Pacific oceans (Wade et al., 2011). Numberger et al. (2009) recognized four morphotypes of G. ruber (white) on the basis of morphometric analysis and named them "type a or normal, type b or platys, type c or elongate, and type d or kummerform."

G. ruber is an important species inhabiting the top mixed layer (Aze et al., 2011). It exhibits oligotrophic behavior and serves as an important proxy for the thickness of the mixed layer (Sinha et al., 2006). This species has been effectively used for the stable oxygen isotope as well as Mg/Ca ratios for reconstruction of past sea-surface temperatures. G. ruber is a characteristic species for the Agulhas Current and constitutes 40%–60% of the modern Agulhas fauna (Simon et al., 2013). The average abundance of G. ruber in Hole U1474A is higher during the Late Pliocene to recent and rare during the Early Pliocene.

Globigerinoides tenellus (Parker 1958)

(Plate P6, figures 11–14)

Type species: Globigerinoides tenella Parker (1958)

Reference: Parker (1958), Frerichs (1971), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-16H-5, 77–79 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. tenellus can be distinguished by its small, compact test with spinose and cancellate wall (Kennett and Srinivasa, 1983; Aze et al., 2011). The primary aperture is large and circular, with a distinct rim, and placed centrally. It has one supplementary aperture on the spiral side. This species closely resembles Globoturborotalita rubescens, but for its supplementary aperture. In many modern analyses it was included in Globoturborotalita despite having a supplementary aperture (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). Kennett and Srinivasan (1983) included this species in Globigerinoides and considered G. rubescens as the ancestor. Morard et al. (2019), on the basis of molecular genetics, included it in Globigerinoides and assigned G. elongatus as its ancestor.

G. tenellus can be distinguished from G. rubescens by the presence of a supplementary aperture. It is a mixed-layer dweller (Aze et al., 2011), present in tropical to temperate latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In the present study, this species has occurred from Late Pliocene to recent, but is quite low in abundance.

Genus Globigerinoidesella El-Naggar 1971

Type species Globigerina fistulosa Schubert 1910

Globigerinoidesella fistulosa (Schubert 1910)

(Plate P6, figures 15–20)

Basionym: Globigerina fistulosa

Synonyms: Globigerinoides fistulosus, Globigerinoides sacculifera fistulosus, Globigerinoides quadrilobatus hystricosus

Type species: Globigerinoidesella fistulosa Schubert (1910)

References: Schubert (1910), Parker (1967), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Poole and Wade (2019)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-13H-5, 87–89 cm, to 8H-4, 77–79 cm

Remarks. G. fistulosa differs from its ancestor T. sacculifer (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Spezzaferri et al., 2015) in having a large test and fistulose proturbances on the chambers in the final whorl. It has a cancellate surface and differs from a T. sacculifer-type wall in being spinose (Aze et al., 2011). The primary aperture is large, rimmed, and interiomarginal, and there are multiple supplementary sutural apertures on the spiral side.

G. fistulosa is considered to be of great importance in biostratigraphic studies. The LO event of G. fistulosa has been used to mark the top of the Olduvai Normal Event (Srinivasan and Sinha, 1991, 1992; Berggren et al., 1995). Earlier, this event was also used to demarcate the Pliocene/Pleistocene boundary (Berggren et al., 1995; Sinha and Singh, 2008) when the age of the boundary was considered to be 1.8 Ma (Gradstein et al., 2004). After the age of the Pliocene/Pleistocene boundary was lowered to 2.588 Ma (Hilgen et al., 2009; Gibbard et al., 2010; Raffi et al., 2020), this event lost its utility as the boundary marker. This event is still utilized to identify the Gelasian/Calabrian boundary in the sedimentary record. The LO of G. fistulosa has also been used to mark the base of Zone PT1 by Wade et al. (2011), and Singh and Sinha (2022) identified this event close to the Olduvai base in Ocean Drilling Program Hole 762B.

G. fistulosa exhibits several morphotypes. Kennett and Srinivasan (1983) considered the forms with elongated digitations on the last few chambers in the final whorl as G. fistulosa. Belford (1962) erected a new subspecies, Globigerinoides quadrilobatus hystricosus, for the forms that had elongated final chambers with digitations. It was considered a primitive phylogenetically related form to G. fistulosa (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Bolli and Saunders, 1985; Poole and Wade, 2019). Bolli and Saunders (1985) identified the forms resembling G. fistulosa as Globigerinoides trilobus fistulosus, Globigerinoides trilobus cf. fistulosus, and Globigerinoides trilobus A on the basis of the extension of peripheral ends of the last few chambers in fistule-like projections.

The generic assignment of G. fistulosa also underwent revision. Schubert (1910) included this species in the genus Globigerina, which was later included in Globigerinoides. A new genus Globigerinoidesella was introduced by El-Naggar (1971) to differentiate the forms with radially elongated digitate protuberances on chambers from the other species of Globigerinoides (Spezzaferri et al., 2015), with Globigerina fistulosa Schubert as its type species. Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), following André et al. (2013), identify this species as Globigerinoides sacculifer forma fistulosus, a rarely occurring morphotype in the modern plankton. They opine that a clear distinction between morphotypes forming the fistulose and sac-like chambers may be impossible.

Poole and Wade (2019) refrained from classifying the transitional forms with fistulose protuberances occurring until recent as G. fistulosa, and considered them extreme variants of T. sacculifer to maintain the biostratigraphic utility of G. fistulosa. In Hole U1474A, this species occurs in extremely low abundance and was observed intermittently.

Genus Globoquadrina Finlay 1947

Type species Globorotalia dehiscens Chapman, Parr and Collins, 1934

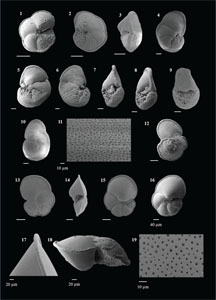

Globoquadrina dehiscens (Chapman, Parr and Collins 1934)

(Plate P7, figures 1–6)

Basionym: Globorotalia dehiscens

Synonym: Globoquadrina dehiscens

Type species: Globoquadrina dehiscens Chapman, Parr and Collins, 1934

References: Chapman et al. (1934), Bolli et al. (1957), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Fox and Wade (2013), Wade et al. (2018), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 23H-7, 54–56 cm

Remarks. G. dehiscens is an important biostratigraphic marker in both tropical and temperate waters (Jenkins, 1971; Srinivasan and Kennett, 1981b). It has a compact test with a flat spiral and strongly convex umbilical side. There are three to four compressed chambers with a triangular outline and wide umbilicus surrounded by the steep walls of the chambers (Wade et al., 2018), which are also referred to as umbilical shoulders (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). The surface is cancellate with circular pores and polygonal ridges. The umbilicus is deep and has apertural tooth.

This cosmopolitan species (Wade et al., 2018) is considered an intermediate dweller by Keller (1985). G. dehiscens is extremely rare in Hole U1474A and is present only in the samples spanning the Late Miocene.

Genus Globorotaloides Bolli, 1957

Type species Globorotaloides variabilis Bolli, 1957

Globorotaloides hexagonus (Natland 1938)

(Plate P7, figures 7–12)

Basionym: Globigerina hexagona

Synonyms: Globorotaloides hexagona, Globoquadrina hexagona, Globorotalia extans Jenkins (1960), Globorotaloides permicrus Blow and Banner (1962), Globigerina clippertonensis McCulloch (1977).

Type species: Globorotaloides hexagonus Natland, 1938

References: Natland (1938), Parker (1962), Lipps (1964), Kennett (1973), Keller (1978), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. hexagonus is an extant form typified by a low trochospiral test with flat spiral side, four to five chambers in the final whorl, and a typical cancellate surface (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017) showing honeycomb-like structure (Coxall and Spezzaferri, 2018). It typically consists of five chambers in the final whorl (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Lam and Leckie, 2020a), but in the present study the four-chambered forms were dominant and five-chambered forms were rare. The surface is coarsely cancellate with T. sacculifer-type wall, with pores in hexagonal pore pits (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983).

G. hexagonus is an extremely rare form restricted to the Indian and Pacific Oceans (Bé and Tolderlund, 1971). It is a deep subthermocline dweller (Ortiz et al., 1996; Birch et al., 2013), commonly occurring in the tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In Hole U1474A, G. hexagonus is extremely rare in occurrence.

Genus Globoturborotalita Hofker 1976

Type species Globigerina rubescens Hofker 1956

Globoturborotalita apertura (Cushman 1918)

(Plate P7, figures 13–20)

Basionym: Globigerina apertura

Synonym: Globigerina (Zeaglobigerina) apertura

Type species: Globoturborotalita apertura Cushman, 1918

References: Cushman (1918), Kennett and Vella (1975), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Iaccarino (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 8H-3, 3–5 cm

Remarks. G. apertura is characterized by a large, low trochospiral test with quadrilobate outline, and a large semicircular aperture with a distinct rim. It has a cancellate surface ultrastructure resembling G. woodi. Blow (1969) considered G. bulloides as the ancestor of G. apertura, but the lack of G. bulloides-type wall and rimmed aperture phylogenetically links it with G. woodi (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983).

G. apertura preferred open ocean mixed-layer habitat (Aze et al., 2011) and ranged from subtropical to temperate latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In the present study, it is a rarely occurring species.

Globoturborotalita decoraperta (Takayanagi and Saito 1962)

(Plate P8, figures 1–4)

Plate P8. Globoturborotalita decorpaerta, Globoturborotalita druryi, Globoturborotalita nepenthes, and Globoturborotalita rubescens.

Basionym: Globigerina druryi decoraperta

Synonym: Globigerina (Zeaglobigerina) decoraperta

Type species: Globoturborotalita decoraperta (Takayanagi and Saito, 1962)

References: Takayanagi and Saito (1962), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Vella (1975), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Iaccarino (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 7H-3, 131–133 cm

Remarks. G. decoraperta closely resembles G. woodi but for its high-spired test, which also distinguishes it from G. apertura because both have a large aperture bordered by a rim. G. decoraperta has a compact test with cancellate surface and wide and deep umbilicus with a large, rimmed aperture. This tropical–subtropical species is a mixed-layer dweller (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Aze et al., 2011).

It is an important biostratigraphic marker but has a quite variable recorded stratigraphic range. The LO of G. decoraperta has been assigned a Late Pliocene age by Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Kaushik et al. (2020), and Lam and Leckie (2020b). Jenkins and Srinivasan (1986), Sinha and Singh (2008), and Singh and Sinha (2022) have reported the LO as Quaternary. The LO of G. decoraperta was observed during the late Early Quaternary in the present study. It is a prominently occurring species in the present work, with a higher relative abundance during the Late Miocene and Pliocene than the Pleistocene in Hole U1474A.

Globoturborotalita druryi (Akers 1955)

(Plate P8, figures 5–8)

Synonym: Globigerina (Zeaglobigerina) druryi

Type species: Globoturborotalita druryi Akers, 1955

References: Akers (1955), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 18H-4, 133–135 cm

Remarks. G. druryi is characterized by a small, compact test with lobate periphery and coarsely pitted surface. It has a distinct low arch aperture with a rim, which distinguishes it from G. woodi (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Lam and Leckie, 2020a).

G. druryi was a mixed-layer dweller (Aze et al., 2011) and inhabited lower latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983).

In the present study, it is a commonly occurring species in the lower part of the core, with high relative abundance (>10%) in the Late Miocene–Early Pliocene part of the core.

Globoturborotalita nepenthes (Todd 1957)

(Plate P8, figures 9–16)

Basionym: Globigerina nepenthes

Synonym: Globigerina (Zeaglobigerina) nepenthes

Type species: Globoturborotalita nepenthes Todd, 1957

References: Todd (1957), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Hornibrook et al. (1989), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 18H-1, 39–41 cm

Remarks. G. nepenthes shows a compactly coiled test with a characteristic thumb-like protruding final chamber, cancellate wall, and broad aperture with distinct rim (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). Its final chamber resembles the tropical insectivorous pitcher plant Nepenthes, from which it derives its name. G. nepenthes differs from its ancestor G. druryi in its final chamber and relatively large test. The wide range of variations in G. nepenthes led to the erection of some other species like Globigerina picassiana (Perconig, 1968) and Globigerina nepenthes delicatula (Brönnimann and Resig, 1971), which were later considered phenotypic variants of G. nepenthes by Kennett and Srinivasan (1983).

This mixed-layer dweller (Aze et al., 2011) lived in warm low latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). G. nepenthes is a frequently occurring species in the lower part of the core and has an average relative abundance of 3%–5%.

Globoturborotalita rubescens (Hofker 1956)

(Plate P8, figures 17–20; Plate P9, figures 1–5)

Plate P9. Globoturborotalita rubescens, Globoturborotalita woodi, Orbulina suturalis, and Orbulina universa.

Basionym: Globigerina rubescens

Synonyms: Globigerina (Zeaglobigerina) rubescens, Globigerina rosacea Bermúdez and Seiglie (1963)

Type species: Globoturborotalita rubescens Hofker (1956)

References: Hofker (1956), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Iaccarino (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-18H-7, 35–37 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. G. rubescens is the only extant species of genus Globorotalita (Brummer and Kučera, 2022). It evolved from G. decoraperta and is distinguished by its small size, relatively delicate test, and small circular aperture. The aperture is bordered by a rim. The surface ultrastructure is cancellate, as well as spinose (Aze et al., 2011). G. rubescens often exhibits pink-pigmented tests, especially in modern waters and Late Quaternary sediments.

G. rubescens prefers open ocean mixed-layer habitat (Aze et al., 2011) and is a tropical to subtropical dweller (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). Parker (1962) and Hemleben et al. (1989) suggested that white tests of G. rubescens are frequently found in bottom sediments underlying temperate waters and suggested that this species is ubiquitous in tropical to temperate surface waters.

In the present work, the relative abundance of this species is very significant and often exceeds 15% of the total faunal composition.

Globoturborotalita woodi (Jenkins 1960)

(Plate P9, figures 6–12)

Synonym: Globigerina (Zeaglobigerina) woodi

Type species: Globoturborotalita woodi Jenkins, 1960

References: Jenkins (1960), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Jenkins (1985), Chaproniere (1988), Spezzaferri (1994), Li and McGowran (2000), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 6H-3, 34–36 cm

Remarks. G. woodi is distinguished by its quadrilobate outline, with a centrally placed, high-arched symmetrically rounded aperture bordered by a distinct rim. It has a cancellate surface ultrastructure with pores located in subhexagonal pore pits.

Pearson et al. (1997), based on isotope studies, assigned surface mixed-layer habitat for G. woodi, whereas Keller (1985) suggested a deeper habitat for this species. G. woodi had a wide latitudinal range from temperate to warm subtropical (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It was a commonly occurring species at mid latitudes in both hemispheres (Lam and Leckie, 2020a; present study). In the present work, G. woodi was a rare species, showing sporadically high abundance in the lower part of the core spanning the Pliocene.

Type species Orbulina universa d'Orbigny, 1839

Orbulina suturalis (Brönnimann 1951)

(Plate P9, figures 13–14)

Synonym: Candorbulina universa Jedlitschka (1934)

Type species: Orbulina suturalis Brönnimann (1951)

References: Brönnimann, (1951), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Norris 1998), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 3H-1, 41–43 cm

Remarks. O. suturalis is a distinct species with a spherical test, areal apertures, and supplementary apertures located along a suture line that joins the previous chambers of the Globigerina stage with the final chamber. The surface ultrastructure is hispid. The large final chamber does not completely envelop the previous chambers, which are visible as low, round projections. The sutural supplementary apertures may sometimes become obscured due to heavy encrustation or secondary infilling, which makes it difficult to identify because the specimen looks like O. universa. Therefore, it sometimes becomes important to locate the projections of the chambers of the Globigerina stage by using a dark-colored dye dripped on the specimen to identify this species.

It has a wide latitudinal range, from tropics to temperate region (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It is widely regarded as a mixed-layer dweller, but Aze et al. (2011) classify it as an open ocean thermocline dweller based on its heavy δ18O signatures.

This species shows sporadic occurrence in Hole U1474A, with abundance rarely exceeding 1% during the Quaternary and Late Pliocene, whereas the Early Pliocene witnessed quite high abundance, occasionally exceeding 15% of the total population.

Orbulina universa (d'Orbigny 1839)

(Plate P9, figures 15–17; Plate P10, figures 1–2)

Type species: Orbulina universa d'Orbigny, 1839

Variant: Orbulina bilobata d'Orbigny (Biorbulina bilobata)

References: d'Orbigny (1839), d'Orbigny (1846), Blow (1956), Postuma (1971), Stainforth et al. (1975), Saito et al. (1981), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Loeblich and Tappan (1994), de Vargas et al. (1999), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. O. universa, a commonly encountered species inhabiting the surface waters of the world oceans from the Subarctic to Subantarctic latitudes (de Vargas et al., 1999), is easily distinguishable by its spherical test formed at the terminal ontogenetic stage (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). The development of a completely spherical form in O. universa is believed to be the result of rapid anagenesis at the early/middle Miocene boundary, followed by morphological stasis (Jenkins, 1968; de Vargas et al., 1999). It consists of a single spherical chamber, which is the final chamber enveloping the early part of the test that represents the preadult Globigerina stage (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). The surface has hispid wall (Aze et al., 2011) and is densely perforate with two distinct pore sizes, of which the larger ones act as the aperture. The size and frequency of pores in O. universa have been used in paleotemperature studies and it has been observed in laboratory experiments that increases in temperature correlate with larger pore diameter (Caron et al., 1987; Bijma et al., 1990). The tests with large diameter and higher porosities occur in tropical latitudes, whereas those with smaller test diameter and lower porosities are characteristic of mid to high latitudes (Bé and Tolderlund, 1971). Molecular genetic data have revealed three cryptic species of O. universa whose distribution is related to hydrographic provinces and sea-surface total chlorophyll-a concentration (de Vargas et al., 1999). The three cryptic species are regionally separated by their dominance as Caribbean species (Type I), Mediterranean species (Type II), and Sargasso species (Type III), with varying pore density and pore/aperture sizes (de Vargas et al., 1999; Morard et al., 2009; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017).

O. universa has largely been considered a mixed-layer dweller, although Aze et al. (2011) marked it as an open ocean thermocline species based on its stable oxygen isotope signatures.

Another variant, O. bilobata, which was previously considered an extant species by Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), has been disregarded as a separate species and included in O. universa (Stainforth et al., 1975; Saito et al., 1981; Rossignol et al., 2011; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Brummer and Kučera, 2022). It is an aberrant form of O. universa that develops a second terminal chamber in response to higher food availability (Robbins, 1988; Hemleben et al., 1989). The relative abundance of O. universa is higher during the Pliocene as compared to Quaternary, occasionally exceeding 10% during the Pliocene.

Genus Sphaeroidinella Cushman 1927

Type Species Sphaeoridina bulloides d'Orbigny var. dehiscens Parker and Jones, 1865

Sphaeroidinella dehiscens (Parker and Jones 1865)

(Plate P10, figures 3–11)

Basionym: Sphaeroidina bulloides var. dehiscens

Synonyms: Sphaeroidinella dehiscens immatura Cushman (1919), Sphaeroidinella dehiscens excavata Banner and Blow (1965), Sphaeroidinella dehiscens ionica ionica Cita and Ciaranfi (1972), Sphaeroidinella ionica evoluta Cita and Ciaranfi (1972)

Type species: Sphaeroidinella dehiscens Parker and Jones, 1865

References: d'Orbigny (1865), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Pearson (1995), Malmgren et al. (1996), Kučera (1998), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-16H-4, 67–69 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. S. dehiscens is an extant species characterized by a large, ovoid test with three chambers in the final whorl. It has a deep umbilicus, a large primary aperture, and a secondary sutural aperture. The apertures are bordered by crenulated lip. It has a nonspinose cancellate wall with cortex (Aze et al., 2011). S. dehiscens differs from S. paenedehiscens in having secondary apertures (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983).

The development of a secondary aperture in the test of S. dehiscens is considered an important event in Late Neogene biostratigraphy. Berggren et al. (1985) assigned an age of 5.1 Ma to the evolutionary appearance of secondary apertures, which was revised by Malmgren et al. (1996) to 5.5 Ma. The evolution of S. dehiscens from S. paenedehiscens by development of minute secondary apertures in the latest Miocene (Malmgren et al., 1996; Kučera, 1998) was used to define the base of Zone N19 (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). These forms with minute secondary apertures were referred to as S. dehiscens forma immatura (Kučera, 1998). Such forms were also encountered in the lower part of the studied core in the present study (Plate P25, figures 17–19). The transition from such minute secondary aperture to a large secondary aperture covering the spiral side occurred after the mid Pliocene (Malmgren et al., 1996) and marked the appearance of S. dehiscens sensu stricto (Bandy, 1964).

Sphaeroidinella is a monospecific genus that develops the cortex at the terminal stage of its life cycle, which makes the preadult specimens similar to T. sacculifer (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Brummer and Kučera, 2022).

S. dehiscens is an open ocean thermocline dweller (Aze et al., 2011), ranging from tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It occurs in extremely low abundance in Hole U1474A.

Genus Sphaeroidinellopsis Banner and Blow 1959

Type species Globigerina seminulina Schwager 1866

Sphaeroidinellopsis kochi (Caudri 1934)

(Plate P10, figures 12–19; Plate P11, figures 1–5)

Plate P11. Sphaeroidinellopsis kochi, Sphaeroidinellopsis paenedehiscens, and Sphaeroidinellopsis seminulina.

Synonym: Sphaeroidinella rutschi Cushman and Renz (1941), Sphaeroidinella multiloba LeRoy (1944), Globigerina grimsdalei Keijzer (1945), Sphaeroidinellopsis hancocki Bandy (1975).

Type species: Sphaeroidinellopsis kochi Caudri, 1934

References: Caudri (1934), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Pearson (1995), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 14H-3, 21–23 cm

Remarks. S. kochi differs from Sphaeroidinellopsis seminulina in having more than three chambers (Kennett and Srinivasa, 1983), a wide open umbilicus, and a larger aperture. It has four to five chambers in the final whorl, with last chamber of characteristic sacculiferid shape (Bolli and Saunders, 1985). The wall is distinctly cancellate in the specimens that lack a cortex, whereas those with cortex exhibit smooth surface. The aperture has crenulated margin like S. seminulina. In some specimens of S. kochi, series of supplementary sutural apertures were visible on the spiral side, but these appear to be more of a diagenetic signature rather than a distinguishing morphological feature.

S. kochi was a thermocline dweller (Aze et al., 2011) found in tropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In Hole U1474A, it is found in low abundance.

Sphaeroidinellopsis paenedehiscens (Blow 1969)

(Plate P11, figures 6–8)

Basionym: Sphaeroidinella subdehiscens paenedehiscens

Synonym: Sphaeroidinellopsis sphaeroides Lamb (1969).

Type species: Sphaeroidinellopsis paenedehiscens Blow, 1969

References: Blow (1969), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 15H-4, 67–69 cm

Remarks. S. paenedehiscens has a large test with rounded periphery, with three inflated chambers in the final whorl, and a heavy cortex that obscures the pores and sutures. The wall is cancellate with smooth cortex (Aze et al., 2011). The aperture is elongate and has a crenulated lip. S. paenedehiscens differs from S. seminulina in having a large test, more spherical outline, and a more elongated aperture. Another important distinguishing feature is the compactness of the test that gives the impression of two chambers in the final whorl, unlike S. seminulina, in which the three chambers are distinct.

S. paenedehiscens was an open ocean thermocline dweller (Aze et al., 2011) found in tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In Hole U1474A, S. paenedehiscens occurs in extremely low abundance in the Pliocene samples.

Sphaeroidinellopsis seminulina (Schwager 1866)

(Plate P11, figures 9–18)

Basionym: Globigerina seminulina

Synonym: Sphaeroidinellopsis seminulina seminulina, Sphaeroidinella spinulosa Subbotina (1958), Sphaeroidinellopsis subdehiscens Blow (1959).

Type species: Sphaeroidinellopsis seminulina Schwager, 1866

References: Schwager (1866), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Lam and Leckie (2020a)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 12H-1, 71–73 cm

Remarks. S. seminulina is characterized by a compact test with a broadly ovate to trilobulate outline and is covered with a heavy cortex (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). It has three chambers in the final whorl, a cancellate wall that shows smooth texture due to the cortex, and an elongate umbilical aperture with crenulated margin. The coarsely perforate surface has cancellate wall, which is covered by a heavy cortex giving it a glossy appearance (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In almost all the specimens encountered, the surface of the last chamber of the final whorl showed blunt, spine-like extensions of the cortex.

A lot has been discussed about the number of chambers in the final whorl of S. seminulina, and several species/subspecies have been proposed. The original description of S. seminulina by Schwager (1866) indicates three-chambered form, which was different from the four-chambered neotype selected by Banner and Blow (1960). Another species, S. subdehiscens, was erected by Blow (1959) for three-chambered forms. Later, Srinivasan and Kennett (1981b), on comparison of both the forms, concluded that S. subdehiscens was a junior synonym of S. seminulina. Lam and Leckie (2020a) included the forms with three to three and a half chambers in S. seminulina. In the present work, we have adhered to the concept of Kennett and Srinivasan (1983) and included only three-chambered forms in S. seminulina. The forms with more than three chambers in the final whorl were included in S. kochi.

S. seminulina was a thermocline dweller (Aze et al., 2011) extending in the tropical to warm subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In Hole U1474A, S. seminulina showed extremely high abundance during the Late Miocene–Early Pliocene, often exceeding 10% of the faunal population, whereas during the Late Pliocene it showed extremely low abundance.

Genus Trilobatus Spezzaferri et al. 2015

Type species Trilobatus trilobus

Trilobatus quadrilobatus (d'Orbigny 1846)

(Plate P12, figures 1–4)

Basionym: Globigerina quadrilobata

Synonym: Globigerinoides quadrilobatus, Globigerinoides primordius

Type species: Trilobatus quadrilobatus d'Orbigny (1846)

References: d'Orbigny (1846), Banner and Blow (1960), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Spezzaferri et al. (2018), Poole and Wade (2019)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. T. quadrilobatus is characterized by three and a half to four chambers, a T. sacculifer-type wall, and a low arch primary aperture bordered by a thin rim centered over the antepenultimate chamber (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). There are two supplementary apertures on the spiral side.

This species closely resembles Trilobatus immaturus but for its higher aperture (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). In the present work, both species are clubbed into T. quadrilobatus. André et al. (2013) included it in T. sacculifer based on molecular genetic studies.

T. quadrilobatus is a cosmopolitan species (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Spezzaferri et al., 2018) and prefers mixed-layer habitat (Chaisson and Ravelo, 1997). It is a consistently occurring species with low abundance in Hole U1474A.

Trilobatus sacculifer (Brady 1877)

(Plate P12, figures 5–14)

Basionym: Globigerina sacculifera

Synonyms: Globigerinoides sacculifer, Globigerina bulloides var. recumbens Rhumbler (1901)

Type species: Trilobatus sacculifera Brady (1877)

References: Brady (1877), Kennett (1973), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Spezzaferri et al. (2018), Poole and Wade (2019), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. T. sacculifer is an important mixed-layer dwelling species, abundant in tropical–subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Schmuker and Schiebel, 2002; Aze et al., 2011; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). It has a unique morphological appearance and can be distinguished by its compressed, sac-like final chamber, which shows several modifications. The test has a T. sacculifer-type wall, a high arch, and rimmed primary aperture. There are numerous supplementary apertures on the spiral side.

T. sacculifer has been studied in great detail by several authors for its micropaleontological as well as molecular genetic aspects (e.g., Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Bolli and Saunders, 1985; André et al., 2013; Spezzaferri et al., 2015, 2018; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017; Poole and Wade, 2019; Lam and Leckie, 2020a). It was considered a descendant of the lineage triloba-immaturus-quadrilobatus-sacculifer by Kennett and Srinivasan (1983) and included in the Group B stock of their classification of Globigerinoides. As previously discussed, André et al. (2013) grouped triloba, immaturus, quadrilobatus, and sacculifer as the morphospecies of T. sacculifer. Lam and Leckie (2020a) have preferred the biological definition of this species and grouped T. triloba with T. sacculifer due to their similar stratigraphic ranges in the northwest Pacific Ocean. Schiebel and Hemleben (2017) opine that of the various morphotypes, sacculifer is the valid species name because it best includes the entire range of the morphotypes and have assigned terminology like forma trilobus, forma quadrilobatus and forma sacculifer to express their concept of genotype. Poole and Wade (2019) encountered several forms of T. sacculifer with an elongate fistulose projection from the final chamber and considered it to be the plexus form of T. sacculifer.

Although in modern plankton, all these morphotypes are considered conspecific (André et al., 2013), in the fossil record they are still regarded as distinct species due to their different stratigraphic ranges (Spezzaferri et al., 2018). The census data suggest low abundance of this commonly occurring species in Hole U1474A.

Trilobatus trilobus (Reuss 1850)

(Plate P12, figures 15–18)

Synonym: Globigerinoides triloba, Globigerinoides trilobus Spezzaferri (1994)

Type species: Trilobatus triloba Reuss (1850)

References: Reuss (1850), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Spezzaferri (1994), Fox and Wade (2013), Spezzaferri et al. (2015), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Poole and Wade (2019)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. T. trilobus is characterized by its low trochospiral test with three chambers in the last whorl, with the final chamber being larger than the previous two. The surface ultrastructure is cancellate with T. sacculifer-type wall. The primary aperture is a narrow slit-like, sometimes low arch, and there are two to three secondary apertures on the spiral side.

There has been a large debate on the status of T. trilobus as a separate species. Earlier, this species was considered under the genus Globigerinoides, which was later included in the genus Trilobatus (Spezzaferri et al., 2015). Spezzaferri et al. (2015), using stratophenetic and molecular genetic data, proved the polyphyletic origin of the genus Globigerinoides, a trait previously discussed by several authors, for example, Takayanagi and Saito (1962), Keller (1981), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Jenkins (1985), Spezzaferri and Premoli Silva (1991), and Spezzaferri (1994). André et al. (2013) conducted molecular genetic studies on modern forms and concluded that the species trilobus, immaturus, quadrilobatus, and sacculifer are the morphotypes of the same species, which are not separated by the biologists and included in T. sacculifer. However, the fossils of these forms are still considered separate species and used exclusively for paleoceanographic and biostratigraphic studies (Spezzaferri et al., 2018; Poole and Wade, 2019; Lam and Leckie, 2020a, 2020b). Schiebel and Hemleben (2017) described four common morphotypes of the modern T. sacculifer (Globigerinoides sacculifer, as mentioned by the authors): forma trilobus, forma quadrilobatus, forma immaturus, and forma sacculifer. All these forms are considered morphotypes of T. sacculifer due to its range that includes the entire range of morphotypes including the plexus forms (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). The focus of the present work is on the paleoceanographic reconstruction of the Agulhas Current, so these forms are considered as separate distinct species.

T. trilobus is very abundant in the tropics as well as commonly found in the mid latitudes (Spezzaferri et al., 2018) and prefers mixed-layer habitat (Pearson et al., 1997). In the present work, this species is found consistently, with an abundance of 2%–3%.

Genus Turborotalita Blow and Banner, 1962

Type Species Truncatulina humilis Brady 1884

Turborotalita quinqueloba (Natland 1938)

(Plate P13, figures 1–7)

Basionym: Globigerina quinqueloba

Synonym: Globigerina quinqueloba

Type species: Turborotalita quinqueloba Natland, 1938

References: Natland (1938), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Jenkins (1985), Pearson and Wade (2009), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Pearson and Kučera (2018), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm

Remarks. T. quinqueloba shows wide morphological variability and resembles many forms with ampullate final chambers (Brummer and Kučera, 2022). The test consists of four and a half to five chambers in the final whorl, with the final chamber modified in a flap-like extension, which resembles a lip in some morphotypes and is modified like a bulla in others. The surface ultrastructure consists of a primarily smooth wall with the development of G. ruber/T. sacculifer-type wall, also known as Turborotalita-type wall ultrastructure (Hemleben and Olsson, 2006). Another important feature is the distinctly spinose surface of the last chamber, with short, stunted triangular spines. It is a species inhabiting subpolar latitudes (Bé and Tolderlund, 1971). T. quinqueloba is rare in Hole U1474A and occurs sporadically, with the relative abundance below 0.5%.

Turborotalita humilis (Brady 1884)

(Plate P13, figure 8)

Basionym: Truncatulina humilis

Synonym: Turborotalita humilis, Turborotalita cristata

Type species: Turborotalita humilis Brady, 1884

References: Brady (1971), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Bolli and Saunders (1985), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Remarks. T. humilis is an extant form (Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017), characterized by a small, compact test with circular equatorial outline and six chambers in the final whorl. The last chamber is characteristically modified in the form of tongue-like extension over the umbilicus and has several infralaminal apertures (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983). The extension of the last chamber also resembles bulla that wraps the umbilicus and ends in a series of finger-like extensions over the umbilical sutures (Bolli and Saunders, 1985). The wall is spinose and shows cancellate structure (Aze et al., 2011), which is often obscured due to encrusting.

T. humilis is a mixed-layer dweller found in tropical–subtropical latitudes (Kennett and Srinivasan, 1983; Aze et al., 2011). It is extremely rare in Hole U1474A and occurred sporadically.

Family GLOBIGERINITIDAE Bermúdez 1961, revised Li 1987; Pearson and Wade 2009

Genus Globigerinita Brönnimann 1951

Type species Globigerinita naparimaensis Brönnimann 1951

Globigerinita glutinata (Egger 1893)

(Plate P13, figures 9–19)

Basionym: Globigerina glutinata

Synonyms: Globigerinita glutinata glutinata, Globigerinita naparimaensis Brönnimann (1951), Globigerinita incrusta Akers (1955), Globigerinita parkerae Bermúdez (1961), Globigerinita flparkerae Brönnimann and Resig (1971)

Type species: Globigerinita glutinata Egger, 1893

References: Egger (1893), Parker (1962), Lipps (1964), Fleisher (1974), Keller (1978), Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Chaisson and Leckie (1993), Spezzaferri (1994), Pearson (1995), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), Pearson, Wade and Huber (2018), Lam and Leckie (2020a), Brummer and Kučera (2022)

Observed stratigraphic range: 361-U1474A-25H-7, 26–28 cm, to 1H-1, 0–2 cm