Druitt, T.H., Kutterolf, S., Ronge, T.A., and the Expedition 398 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 398

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.398.205.2025

Data report: visible to shortwave infrared (VSWIR) spectroscopic scanning of selected core sections from Holes U1589A and U1591C, IODP Expedition 398, Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field1

Molly C. McCanta,2 C.J. Leight,3 Mackenzie Camp,3 Steffen Kutterolf,2 Tim Druitt,2 Thomas A.M. Ronge,2 Sarah Beethe,2 Alexis Bernard,2 Carole Berthod,2 Hehe Chen,2 Acacia Clark,2 Susan DeBari,2 Tatiana I.M. Fernandez-Perez,2 Ralf Gertisser,2 Christian Hübscher,2 Raymond M. Johnston,2 Christopher Jones,2 K. Batuk Joshi,2 Günther Kletetschka,2 Olga Koukousioura,2 Michael Manga,2 Iona McIntosh,2 Antony Morris,2 Paraskevi Nomikou,2 Katharina Pank,2 Ally Peccia,2 Paraskevi N. Polymenakou,2 Jonas Preine,2 Masako Tominaga,2 Adam Woodhouse,2 and Yuzuru Yamamoto2

1 McCanta, M.C., Leight, C.J., Camp, M., Kutterolf, S., Druitt, T., Ronge, T.A., Beethe, S., Bernard, A., Berthod, C., Chen, H., Clark, A., DeBari, S., Fernandez-Perez, T.I., Gertisser, R., Hübscher, C., Johnston, R.M., Jones, C., Joshi, K.B., Kletetschka, G., Koukousioura, O., Manga, M., McIntosh, I., Morris, A., Nomikou, P., Pank, K., Peccia, A., Polymenakou, P.N., Preine, J., Tominaga, M., Woodhouse, A., and Yamamoto, Y., 2025. Data report: visible to shortwave infrared (VSWIR) spectroscopic scanning of selected core sections from Holes U1589A and U1591C, IODP Expedition 398, Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field. In Druitt, T.H., Kutterolf, S., Ronge, T.A., and the Expedition 398 Scientists, Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 398: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.398.205.2025

2 Expedition 398 Scientists’ affiliations. Correspondence author: mmccanta@utk.edu

3 Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, USA.

Abstract

A main scientific objective of International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 398 Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field was to reconstruct the history of the Christiana-Santorini-Kolumbo volcanic field to allow for better hazard planning and risk mitigation. Identification of tephra layers in sediments has become increasingly important to inform present-day hazard assessment and better constrain the temporal development and evolution of volcanic systems. However, tephra and sediment composition can vary spatially and temporally; their identification is not always routine, nor straightforward, especially when of small volume, such as with small eruptions or distal deposition. Here, we employ visible to shortwave infrared spectroscopy to identify tephra layers from the background marine sediment present in core sections collected during Expedition 398. Core photographs collected shipboard are used to ascertain the presence of visible tephra units and highlight regions of further study as potential cryptotephra.

1. Introduction

Understanding the frequency, magnitude, and nature of explosive volcanic eruptions is essential for hazard planning and risk mitigation. Explosive volcanic eruptions can disperse large amounts of pyroclastic material (tephra) over a wide geographic range. When preserved in the sedimentary record, these layers can serve as stratigraphic marker beds that can be used to infer the timing and magnitude of eruptive activity (e.g., Federman and Carey, 1980; Dugmore, 1989; Brown et al., 1992; Carter et al., 1995; Eden et al., 2001; Knudsen and Eirı́ksson, 2002; Larsen et al., 2002; Svensson et al., 2006) and provide volcanic material to analyze for constraints on preeruptive storage and eruptive conditions (e.g., Cassidy et al., 2014; Ponomareva et al., 2015).

However, terrestrial stratigraphic tephra records can be patchy and incomplete because of subsequent erosion and burial processes. In contrast, the marine sedimentary record commonly preserves a more complete historical record of volcanic activity because individual events are archived within continually accumulating marine sediments (e.g., Paterne et al., 1988; Ortega-Guerrero and Newton, 1998; Wulf et al., 2004, 2012; de Fontaine et al., 2007; Bertrand et al., 2008; Gudmundsdóttir et al., 2012). Although thick tephra layers are often identifiable by changes in sediment color and/or texture, thinner tephra layers may also be present that are not visible to the naked eye (e.g., Freundt et al., 2021). Often these so-called cryptotephra are more difficult to identify and require time-consuming and destructive sediment dissolution, point counting, petrography, geochemistry, and microscopy work. Although potentially difficult to identify, characterizing these cryptotephra is of great importance when constraining volcanic history because smaller eruptions are more frequent than large ones (e.g., Siebert et al., 2015; Papale, 2018), thereby resulting in more immediate hazards to surrounding populations. Additionally, these smaller, more frequent eruptions are of high significance geologically because they may provide insight into the mechanisms by which a volcano rebuilds following a cataclysmic eruption (e.g., Lipman and Mullineaux, 1981; Harris et al., 2003; Ryan et al., 2010; Watt, 2019; Shevchenko et al., 2020) and the relationships between small and large eruptions (e.g., Caricchi et al., 2021).

Prior work has demonstrated that visible to shortwave infrared (VSWIR) spectroscopy is a powerful, nondestructive method by which to distinguish volcanic tephra from background marine sediment (McCanta et al., 2015). Here, we present VSWIR scans of selected core sections from International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 398 Holes U1589A and U1591C to identify potential tephra horizons for future sampling. In addition to VSWIR data for individual core sections, results of spectral absorption band fitting procedures are presented to verify that tephra can be distinguished from surrounding nonvolcanic sediments. VSWIR spectra are made available in spreadsheet form in the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) database.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Drill sites and settings

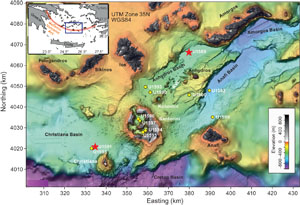

Hole U1589A is located at a water depth of 484 m in the eastern portion of the Anhydros Basin, ~10 km southwest of Amorgos Island (Figure F1). Site U1589 was targeted because it sits in a location determined to receive input from both Santorini and Kolumbo volcanoes. This location was drilled to provide a comprehensive stratigraphy of volcano-sedimentary fill within the Anhydros Basin for use in documenting the presence of volcanic events, reconstructing basin evolution, and linking volcanism and tectonics (Druitt et al., 2022). Hole U1589A was drilled to 446.7 meters below seafloor (mbsf) (Druitt et al., 2024a).

Hole U1591C is located at a water depth of 514 m in the Christiana Basin, ~8 km northwest of Christiana Island and ~20 km southwest of Santorini (Figure F1). Site U1591 was targeted because its location suggested input from Christiana, Santorini, and Milos volcanoes and because the volcano-sedimentary fill of the deeper basin (compared to the Anhydros and Anafi Basins) could potentially record an earlier history of the Christiana-Santorini-Kolumbo volcanic field (Druitt et al., 2022). Hole U1591C was drilled to 902.9 mbsf (Druitt et al., 2024a).

2.2. Visible to shortwave infrared core scanning and data analysis

The VSWIR spectra of 40 archive sections (Table T1) from Holes U1589A and U1591C were acquired under ambient conditions from 0.4 to 2.5 mm using a portable OreXpress field spectrometer transported to the Gulf Coast Repository at Texas A&M University (USA). Sections were analyzed every 10 mm, a resolution used to minimize overlap of spectral spot size. White reference spectra of a Spectralon standard were collected every 15 unknown spectra, and all data were processed by first applying a white reference correction.

Preliminary tephra identification was completed using the 0.9 µm absorption feature previously identified as resulting from the presence of tephra (McCanta et al., 2015). To calculate this spectral feature (BDI1000VIS), the reflectance maximum between 0.442 and 0.992 µm was first identified. This was accomplished by fitting a ninth-order polynomial to the spectrum in this region, evaluating the polynomial at each wavelength point, and finding the maximum value (Rmax). This reflectance maxima was then used to normalize the reflectance values between 0.883 and 1.023 µm, and the BDI1000VIS parameter was calculated by computing the sum of 1.0 minus the normalized reflectance values (Equation 1):

(1)

where Ri is the reflectance value at the ith wavelength between 0.883 and 1.023 µm.

The 2.2 and 2.35 µm absorption band depth (BD) parameters (BD2p2 and BD2p35) were determined according to Equation 2,

(2)

where RC is the reflectance at the center of the spectral band and RC* is the modeled reflectance at the center of the band (defined in Equations 3–5).

(3)

(4)

(5)

RC* is therefore a linear fit between the long wavelength (λL) and short wavelength (λS) areas outside the designated band, and λC is the wavelength of the true band minima (following Pelkey et al., 2007; see McCanta et al., 2015 for a more detailed discussion of band parameters). These calculations result in nondimensional numbers for each parameter used to determine the depth of the absorption feature.

3. Results

3.1. VSWIR spectral trends

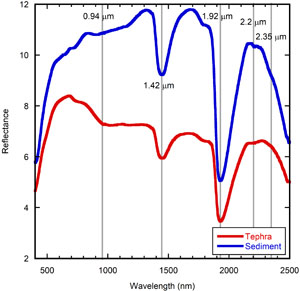

Several key absorption features between 0.4 and 2.5 µm that allow for tephra to be distinguished from background marine sediment are evident (Figure F2). In regions consisting of visible tephras, an absorption feature is present at 0.94 µm, attributable to the recognized 1 µm feature that is related to ferrous iron (Fe2+) in glass, specifically to spin crystal field transitions of Fe2+ in octahedral coordination (consistent with short-range order in glass) (e.g., Burns, 1993; Keppler, 1992). A contribution from iron in mafic minerals such as pyroxene (two strong absorption features with minima near 1 and 2 µm), olivine (broad feature near 1 µm), or FeTi oxides (hematite = strong absorption feature near 0.9 µm; magnetite = weak feature near 1.1 µm) is also possible (e.g., Adams, 1974; King and Ridley, 1987; Cloutis, 2002; Muirhead et al., 2009). This absorption feature, commonly referred to as the 1 µm feature, is only observed in tephra-dominated spectra and has been shown to be diagnostic of tephra concentrations down to 15% by volume (McCanta et al., 2015).

In regions dominated by nonvolcanic sediment (hereafter “sediment”), an absorption feature due to metal-OH absorptions in clay minerals is evident at ~2.21 µm (Figure F2). A subtle feature at ~2.35 µm is also present. Both the ~2.21 and ~2.35 µm features are often anticorrelated with the 1 µm feature; that is, regions with high tephra concentrations have low sediment concentrations and regions with low tephra concentrations have high sediment concentrations. Previous work has shown the 2.21 and 2.35 µm features to be distinguishable in samples with ≥50% sediment in simple sediment + tephra mixtures (McCanta et al., 2015).

Additional spectral features evident in scanned sections include the ~1.4 µm overtone band (OH stretch) and ~1.9 µm combination overtone (H2O symmetric and asymmetric stretches) (Figure F2). These water-related features are present in both tephra and sediment regions and are indicative of the wet state of the cores (which were not dried prior to VSWIR analysis) rather than the presence of hydrous minerals. Although the sediments present in the core sections contain phyllosilicate minerals, which would result in spectrally diagnostic features, the ~1.4 and 1.9 µm features observed are likely the result of variable amounts of surface and adsorbed water, regardless of sample type, in addition to bound water in phyllosilicate minerals. These features are therefore not used to distinguish between tephra and background sediment.

3.2. Identification of tephra layers using spectral band parameters

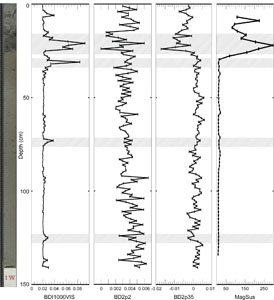

Spectral data for the 40 archive sections were collected and evaluated using the spectral summary parameters described above. Variations in BDI1000VIS, BD2p2, and BD2p35 were compared with core photographs taken shipboard to determine if visible tephra layers were observed spectrally. Results for one section (398-U1589A-44F-2A) with a clearly visible tephra layer (16–27 cm depth within core section) are plotted in Figure F3. This section was identified shipboard as ooze (Druitt et al., 2024a). Section 44F-2 occurred in Subunit IIC, described as ooze and mud with minor volcanics. Strong increases in BDI1000VIS are observed in the visible tephra unit, indicative of a more Fe-rich mineralogy than found in the background sediment. Corresponding decreases in the parameters related to clay mineralogy, BD2p2, and BD2p35 are also observed in the visible tephra unit resulting from decreased clay content in the sediment due to the increased proportion of volcaniclastic sediment.

Figure F3. Nondimensional spectral parameters BDI1000VIS, BD2p2, and BD2p35 and onboard SHMSL MS vs. core photograph.

In addition to VSWIR spectroscopy, magnetic susceptibility (MS) measurements were used to distinguish tephra units from nonvolcanic sediment (e.g., Rasmussen et al., 2003; Peters et al., 2010; McCanta et al., 2015). During Expedition 398, MS analyses were collected shipboard on archive sections using a Bartington MS2E sensor as part of the Section Half Multisensor Logger (SHMSL). The utility of comparing these MS measurements to the onshore VSWIR analyses is limited, however, because the MS data has significantly coarser resolution (2 cm/analysis versus <1 cm/analysis for VSWIR), suggesting that thinner tephra units may be missed. Despite this caveat, MS data for Section 398-U1589A-44F-2A are plotted, and it is evident that increases in BDI1000VIS and MS both correlate with the visible tephra layer (Figure F3).

When attempting to identify regions of interest for cryptotephra, prior work has shown neither BD2p2 nor BD2p35 to be particularly sensitive to the introduction of a volumetrically small cryptotephra layer (McCanta et al., 2015). For this reason, the spectral parameter BDI1000VIS was focused on for identifying potential cryptotephra layers. In Section 398-U1589A-44F-2A, three additional regions were identified using BDI1000VIS as having potentially elevated volumes of tephra (patterned intervals in Figure F3). Section depths 29–34 and 71–76 cm do not correspond to visually continuous tephra layers but with patchy tephra material, potentially reworked through bioturbation (Figure F3). These do not appear to be regions of interest for cryptotephra. Section depth 122–127 cm exhibits a small peak in BDI1000VIS that does not correspond to either a visible tephra layer or patchy tephra pockets. This makes it a candidate for a cryptotephra unit. To verify, a physical sample from the region would need to be disaggregated, cleaned, and point counted following the methods of Le Friant et al. (2008) and McCanta et al. (2015) to determine if the tephra content was above background and therefore a true cryptotephra. Additionally, glass chemistry should be acquired to fully distinguish between reworking and primary volcanic events.

4. Acknowledgments

We thank the crew, staff, and technicians of JOIDES Resolution from Expedition 398, as well as the staff of the Gulf Coast Repository, in particular Michelle Penkrot and Lisa Crowder, for their help in setting up the spectrometer and automated core slide and completing the VSWIR core scanning. We acknowledge travel support for US scientists by USSSP and postexpedition award funding to M.C. McCanta allowing for travel to the Gulf Coast Repository for core scanning.

References

Adams, J.B., 1974. Visible and near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectra of pyroxenes as applied to remote sensing of solid objects in the solar system. Journal of Geophysical Research (1896-1977), 79(32):4829–4836. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB079i032p04829

Bertrand, S., Castiaux, J., and Juvigné, E., 2008. Tephrostratigraphy of the late glacial and Holocene sediments of Puyehue Lake (Southern Volcanic Zone, Chile, 40°S). Quaternary Research, 70(3):343–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yqres.2008.06.001

Brown, F.H., Sarna-Wojcicki, A.M., Meyer, C.E., and Haileab, B., 1992. Correlation of Pliocene and Pleistocene tephra layers between the Turkana Basin of East Africa and the Gulf of Aden. Quaternary International, 13–14:55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/1040-6182(92)90010-Y

Burns, R.G., 1993. Mineralogical Applications of Crystal Field Theory: Cambridge (Cambridge University Press). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511524899

Caricchi, L., Townsend, M., Rivalta, E., and Namiki, A., 2021. The build-up and triggers of volcanic eruptions. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 2(7):458–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00174-8

Carter, L., Nelson, C.S., Neil, H.L., and Froggatt, P.C., 1995. Correlation, dispersal, and preservation of the Kawakawa Tephra and other late Quaternary tephra layers in the Southwest Pacific Ocean. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 38(1):29–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288306.1995.9514637

Cassidy, M., Watt, S.F.L., Palmer, M.R., Trofimovs, J., Symons, W., Maclachlan, S.E., and Stinton, A.J., 2014. Construction of volcanic records from marine sediment cores: a review and case study (Montserrat, West Indies). Earth-Science Reviews, 138:137–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.08.008

Cloutis, E.A., 2002. Pyroxene reflectance spectra: Minor absorption bands and effects of elemental substitutions. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 107(E6):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JE001590

de Fontaine, C.S., Kaufman, D.S., Scott Anderson, R., Werner, A., Waythomas, C.F., and Brown, T.A., 2007. Late Quaternary distal tephra-fall deposits in lacustrine sediments, Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. Quaternary Research, 68(1):64–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yqres.2007.03.006

Druitt, T., Kutterolf, S., and Höfig, T.W., 2022. Expedition 398 Scientific Prospectus: Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field. International Ocean Discovery Program. https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.sp.398.2022

Druitt, T.H., Kutterolf, S., Ronge, T.A., Beethe, S., Bernard, A., Berthod, C., Chen, H., Chiyonobu, S., Clark, A., DeBari, S., Fernandez Perez, T.I., Gertisser, R., Hübscher, C., Johnston, R.M., Jones, C., Joshi, K.B., Kletetschka, G., Koukousioura, O., Li, X., Manga, M., McCanta, M., McIntosh, I., Morris, A., Nomikou, P., Pank, K., Peccia, A., Polymenakou, P.N., Preine, J., Tominaga, M., Woodhouse, A., and Yamamoto, Y., 2024a. Expedition 398 summary. In Druitt, T.H., Kutterolf, S., Ronge, T.A., and the Expedition 398 Scientists, Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 398: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.398.101.2024

Druitt, T., Kutterolf, S., Ronge, T.A., Hübscher, C., Nomikou, P., Preine, J., Gertisser, R., Karstens, J., Keller, J., Koukousioura, O., Manga, M., Metcalfe, A., McCanta, M., McIntosh, I., Pank, K., Woodhouse, A., Beethe, S., Berthod, C., Chiyonobu, S., Chen, H., Clark, A., DeBari, S., Johnston, R., Peccia, A., Yamamoto, Y., Bernard, A., Perez, T.F., Jones, C., Joshi, K.B., Kletetschka, G., Li, X., Morris, A., Polymenakou, P., Tominaga, M., Papanikolaou, D., Wang, K.-L., and Lee, H.-Y., 2024b. Giant offshore pumice deposit records a shallow submarine explosive eruption of ancestral Santorini. Communications Earth & Environment, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01171-z

Dugmore, A., 1989. Icelandic volcanic ash in Scotland. Scottish Geographical Magazine, 105(3):168–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702548908554430

Eden, D.N., Palmer, A.S., Cronin, S.J., Marden, M., and Berryman, K.R., 2001. Dating the culmination of river aggradation at the end of the last glaciation using distal tephra compositions, eastern North Island, New Zealand. Geomorphology, 38(1):133–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-555X(00)00077-5

Federman, A.N., and Carey, S.N., 1980. Electron microprobe correlation of tephra layers from Eastern Mediterranean abyssal sediments and the Island of Santorini. Quaternary Research, 13(2):160–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/0033-5894(80)90026-5

Freundt, A., Schindlbeck-Belo, J.C., Kutterolf, S., and Hopkins, J.L., 2021. Tephra layers in the marine environment: a review of properties and emplacement processes. In Di Capua, A., De Rosa, R., Kereszturi, G., Le Pera, E., Rosi, M., and Watt, S.F.L. (Eds.), Volcanic Processes in the Sedimentary Record: When Volcanoes Meet the Environment. Geological Society Special Publication, 520. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP520-2021-50

Gudmundsdóttir, E.R., Larsen, G., and Eiríksson, J., 2012. Tephra stratigraphy on the North Icelandic shelf: extending tephrochronology into marine sediments off North Iceland. Boreas, 41(4):719–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3885.2012.00258.x

Harris, A.J., Rose, W.I., and Flynn, L.P., 2003. Temporal trends in lava dome extrusion at Santiaguito 1922–2000. Bulletin of Volcanology, 65(2):77–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-002-0243-0

Keppler, H., 1992. Crystal field spectra and geochemistry of transition metal ions in silicate melts and glasses. American Mineralogist, 77(1–2):62–75.

King, T.V.V., and Ridley, W.I., 1987. Relation of the spectroscopic reflectance of olivine to mineral chemistry and some remote sensing implications. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 92(B11):11457–11469. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB092iB11p11457

Knudsen, K.L., and Eirı́ksson, J., 2002. Application of tephrochronology to the timing and correlation of palaeoceanographic events recorded in Holocene and Late Glacial shelf sediments off North Iceland. Marine Geology, 191(3):165–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(02)00530-3

Larsen, G., Eiríksson, J., Knudsen, K.L., and Heinemeier, J., 2002. Correlation of late Holocene terrestrial and marine tephra markers, north Iceland: implications for reservoir age changes. Polar Research, 21(2):283–290. https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v21i2.6489

Le Friant, A., Lock, E.J., Hart, M.B., Boudon, G., Sparks, R.S.J., Leng, M.J., Smart, C.W., Komorowski, J.C., Deplus, C., and Fisher, J.K., 2008. Late Pleistocene tephrochronology of marine sediments adjacent to Montserrat, Lesser Antilles volcanic arc. Journal of the Geological Society, 165(1):279–289. https://doi.org/10.1144/0016-76492007-019

Lipman, P., and Mullineaux, D., 1981. The 1980 eruptions of Mount St. Helens, Washington. USGS Professional Paper, 1250. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp1250

McCanta, M.C., Hatfield, R.G., Thomson, B.J., Hook, S.J., and Fisher, E., 2015. Identifying cryptotephra units using correlated rapid, nondestructive methods: VSWIR spectroscopy, X-ray fluorescence, and magnetic susceptibility. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 16(12):4029–4056. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GC005913

Muirhead, A.C., Bishop, J.L., and McKeown, N.K., 2009. The VNIR spectral properties of iron oxide/oxyhydroxide mixtures and applications to iron oxides in the Mawrth Vallis region of Mars. Presented at the 40th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, TX, 23–27 March 2009. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2009/pdf/1652.pdf

Ortega-Guerrero, B., and Newton, A.J., 1998. Geochemical characterization of Late Pleistocene and Holocene tephra layers from the Basin of Mexico, Central Mexico. Quaternary Research, 50(1):90–106. https://doi.org/10.1006/qres.1998.1975

Papale, P., 2018. Global time-size distribution of volcanic eruptions on Earth. Scientific Reports, 8(1):6838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25286-y

Paterne, M., Guichard, F., and Labeyrie, J., 1988. Explosive activity of the South Italian volcanoes during the past 80,000 years as determined by marine tephrochronology. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 34(3):153–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(88)90030-3

Pelkey, S.M., Mustard, J.F., Murchie, S., Clancy, R.T., Wolff, M., Smith, M., Milliken, R., Bibring, J.P., Gendrin, A., Poulet, F., Langevin, Y., and Gondet, B., 2007. CRISM multispectral summary products: Parameterizing mineral diversity on Mars from reflectance. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 112(E8). https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JE002831

Peters, C., Austin, W.E.N., Walden, J., and Hibbert, F.D., 2010. Magnetic characterisation and correlation of a Younger Dryas tephra in North Atlantic marine sediments. Journal of Quaternary Science, 25(3):339–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1320

Ponomareva, V., Portnyagin, M., and Davies, S.M., 2015. Tephra without borders: far-reaching clues into past explosive eruptions. Frontiers in Earth Science, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2015.00083

Rasmussen, T.L., Wastegård, S., Kuijpers, A., van Weering, T.C.E., Heinemeier, J., and Thomsen, E., 2003. Stratigraphy and distribution of tephra layers in marine sediment cores from the Faeroe Islands, North Atlantic. Marine Geology, 199(3):263–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(03)00219-6

Ryan, G.A., Loughlin, S.C., James, M.R., Jones, L.D., Calder, E.S., Christopher, T., Strutt, M.H., and Wadge, G., 2010. Growth of the lava dome and extrusion rates at Soufrière Hills Volcano, Montserrat, West Indies: 2005–2008. Geophysical Research Letters, 37(19). https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL041477

Shevchenko, A.V., Dvigalo, V.N., Walter, T.R., Mania, R., Maccaferri, F., Svirid, I.Y., Belousov, A.B., and Belousova, M.G., 2020. The rebirth and evolution of Bezymianny volcano, Kamchatka after the 1956 sector collapse. Communications Earth & Environment, 1(15). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00014-5

Siebert, L., Cottrell, E., Venzke, E., and Andrews, B., 2015. Chapter 12 - Earth’s volcanoes and their eruptions: an overview. In Sigurdsson, H., The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes (Second Edition). Amsterdam (Academic Press), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385938-9.00012-2

Svensson, A., Andersen, K.K., Bigler, M., Clausen, H.B., Dahl-Jensen, D., Davies, S.M., Johnsen, S.J., Muscheler, R., Rasmussen, S.O., Röthlisberger, R., Peder Steffensen, J., and Vinther, B.M., 2006. The Greenland Ice Core Chronology 2005, 15–42ka. Part 2: comparison to other records. Quaternary Science Reviews, 25(23):3258–3267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.08.003

Watt, S.F.L., 2019. The evolution of volcanic systems following sector collapse. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 384:280–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2019.05.012

Wulf, S., Keller, J., Paterne, M., Mingram, J., Lauterbach, S., Opitz, S., Sottili, G., Giaccio, B., Albert, P.G., Satow, C., Tomlinson, E.L., Viccaro, M., and Brauer, A., 2012. The 100–133 ka record of Italian explosive volcanism and revised tephrochronology of Lago Grande di Monticchio. Quaternary Science Reviews, 58:104–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.10.020

Wulf, S., Kraml, M., Brauer, A., Keller, J., and Negendank, J.F.W., 2004. Tephrochronology of the 100ka lacustrine sediment record of Lago Grande di Monticchio (southern Italy). Quaternary International, 122(1):7–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2004.01.028