Flecker, R., Ducassou, E., Williams, T., and the Expedition 401 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 401

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.401.201.2026

Data report: X-ray fluorescence scanning of sediment cores, IODP Expedition 401 Site U1609, SW Iberia Atlantic margin (Portugal)1

Manuel Teixeira,2 Shamar Chin,2 Patricia Standring,2 Yunlang Zhang,3 Isabelle Billy,4 Sarah J. Feakins,2 Zhiyang Li,2 Madeline Mulligan,5 Danielle Noto,2 Fadl Raad,2 Jonathan Stine,2 Xunhui Xu,2 Jesse Yeon,6 Mohamed Z. Yousfi,2 Rachel Flecker,2 Emmanuelle Ducassou,2 Trevor Williams,2 and the Expedition 401 Scientists2

1 Teixeira, M., Chin, S., Standring, P., Zhang, Y., Billy, I., Feakins, S.J., Li, Z., Mulligan, M., Noto, D., Raad, F., Stine, J., Xu, X., Yeon, J., Yousfi, M.Z., Flecker, R., Ducassou, E., Williams, T., and the Expedition 401 Scientists, 2026. Data report: X-ray fluorescence scanning of sediment cores, IODP Expedition 401 Site U1609, SW Iberia Atlantic margin (Portugal). In Flecker, R., Ducassou, E., Williams, T., and the Expedition 401 Scientists, Mediterranean–Atlantic Gateway Exchange. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 401: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.401.201.2026

2 Expedition 401 Scientists' affiliations. Correspondence author: macteixeira@ciencias.ulisboa.pt

3 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Southern California, USA.

4 UMR CNRS 5805, Université de Bordeaux, France.

5 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Iowa, USA.

6 International Ocean Discovery Program, Texas A&M University, USA.

Abstract

International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 401 recovered 983 m of sediment from Portugal’s southwest margin in the northeast Atlantic Ocean at Site U1609 (37°22.6259′ N, 9°35.9120′ W; 1659.5 m water depth). This site was designed to recover the distal contourites deposited by the Mediterranean Overflow Water contour current from the late Miocene to the Pleistocene. We report semiquantitative elemental results from X-ray fluorescence scanning of sediment cores from Site U1609 (Holes U1609A and U1609B) scanned at a 4–5 cm resolution from ~202 to 509 m core depth below seafloor, Method A, equivalent to ~4.52 to ~7.8 Ma. Raw element intensities (in counts per second) for Al, Si, Ca, Ti, Mn, Fe, Rb, Sr, Zr, and Ba are presented here and correlated with lithofacies variations. We also identify biogenic-terrestrial input proportions and illustrate downcore cyclicity and correlation patterns between terrigenous components (Al, Si, Ti, Mn, and Ba), as well as their anticorrelations with biogenic (Ca and Sr) inputs. The cyclical variations in elemental ratios may help stratigraphic correlation between Holes U1609A and U1609B, astronomical tuning of the spliced record, and sedimentary interpretations of changes to the Mediterranean–Atlantic gateway and the bottom current circulation along the Atlantic margin of Portugal before, during, and after the Messinian Salinity Crisis.

1. Introduction

The Mediterranean–Atlantic marine gateway has experienced geomorphologic dynamism and evolution since the Late Miocene (Flecker et al., 2015), mainly through African–Eurasia plate convergence that started in the late Tortonian (Krijgsman et al., 1994) and led to the narrowing and closure of the Betic and Rifian corridors that connected the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean (Krijgsman and Langereis, 2000; Popov et al., 2006; Capella et al., 2018; Bulian et al., 2023). This restricted Mediterranean–Atlantic exchange during the Messinian (Krijgsman et al., 1999a, 1999b, 2018; Flecker et al., 2015) led to the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC) (5.97–5.33 Ma) (Hsü et al., 1973; Garcia-Castellanos and Villaseñor, 2011; Krijgsman et al., 2024; Roveri et al., 2014). With the end of the MSC (5.33 Ma), the Mediterranean–Atlantic gateway was reestablished with the opening of the Gibraltar Strait (e.g., Garcia-Castellanos et al., 2009). These changes in Mediterranean–Atlantic connectivity impacted along-slope sediment deposition in the Gulf of Cádiz and along the Portuguese margin (Hernández-Molina et al., 2011, 2016) and prompted global ocean circulation changes (Voelker et al., 2006).

The Mediterranean Overflow Water (MOW) contour current built contourite drifts along the Gulf of Cádiz and southwest Portuguese margin (Alentejo margin), where it created the Sines contourite drift, a plastered contourite deposit, especially in the Pleistocene (Hernández-Molina et al., 2003, 2011; Teixeira et al., 2019, 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2022, 2024). The Sines contourite drift was formed in the distal part of the Gulf of Cádiz Contourite Drift System (Hernández-Molina et al., 2011) by the action of the MOW, the activity of which has changed over time, influenced by millennial-scale climatic variation and bottom current oscillations during glacial and interglacial periods (Schönfeld and Zahn 2000; Rogerson et al., 2005; Voelker et al., 2006; Toucanne et al., 2007; Hernández-Molina et al., 2014). Moreover, major changes in the Mediterranean gateway and Neogene environmental change are likely to have substantially influenced the overflow (Krijgsman et al., 2024), promoting notable variations in depositional activity with highly varying sedimentation rates (e.g., Expedition 339 Scientists, 2013; Hernández-Molina et al., 2014; Teixeira et al., 2020).

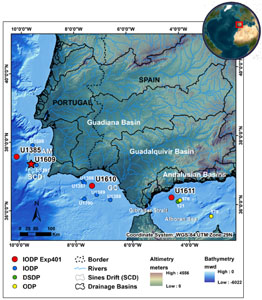

International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 401 drilled Site U1609 (Figure F1) on the southwest Portuguese margin (37°22.6159′N, 09°35.9119′W) in the Sines contourite drift just below the present-day lower branch of the MOW at a 1659.5 m water depth (Flecker et al., 2025). The succession recovered in Hole U1609A and Hole U1609B (20 m south of Hole U1609A) comprises a near-continuous distal sedimentary record of the Late Miocene to ~mid-Pleistocene (~1.24 Ma) (Flecker et al., 2025). Holes U1609A and U1609B reached 610 and 509 m core depth below seafloor, Method A (CSF-A), respectively.

Site U1609 was drilled ~17 km west and downslope (Figure F1) of Expedition 339 Site U1391 (Expedition 339 Scientists, 2013). The sediments at Site U1391 include Pliocene–Quaternary muddy, landward migrating contourites with interbedded sands, hemipelagites, and several layers of mass movement deposits (Hernández-Molina et al., 2011; Teixeira et al., 2019; Rodrigues et al., 2020). Site U1609 is located farther offshore and targets age-equivalent and older sediments (Flecker et al., 2025).

At Site U1609, the Miocene–Pleistocene sediments are mainly characterized by fine sediment with gradational contacts and subtle changes in color and grain size. These sediments are divided into four lithostratigraphic units (Flecker et al., 2025). Unit I (0–344 m CSF-A) is characterized by late Messinian–Pleistocene alternating calcareous mud and calcareous silty mud. Unit II (344–457 m CSF-A) consists of late Tortonian–early Messinian alternating calcareous mud and clayey calcareous ooze. Unit III (457.7–531.5 m CSF-A) contains two different shades (lighter/darker) of Tortonian calcareous mud and clayey calcareous ooze. Coarser sandy and silty deposits, at ~10 cm scale, are observed primarily in Units II and III. Unit IV (531.5–609.3 m CSF-A) contains distinct types of Tortonian clayey calcareous ooze and the dominant brown calcareous muds, mostly with rhythmic <1 m bed thickness (Flecker et al., 2025). Most of these Site U1609 sedimentary facies are mainly attributed to hemipelagic and bottom current processes. This site recovered part of the Sines contourite drift, a middle slope plastered drift formed during the deposition of Unit I (Pliocene and late Messinian). During this depositional phase, the weak bottom currents were vigorous enough at intermediate depths to develop a plastered drift along the middle continental slope (Flecker et al., 2025). Beneath this drfit, there are a few intercalated early Messinian and Tortonian turbidite deposits (Units II–IV) that coincide with regional tectonic events (Riaza and Martines del Olmo, 1996; Sierro et al., 1996; Maldonado et al., 1999; Martinez del Olmo and Martín, 2016).

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanning data will be used to study these events and the distal depositional history of the MOW, spanning the earliest evidence of overflow through the Rifian corridor (~7.8 Ma; Capella et al., 2017) through the MSC in the Mediterranean (5.97–5.33 Ma; Roveri et al., 2014) to the early Pliocene (~4 Ma). XRF scanning yields continuous, semiquantitative elemental concentrations (e.g., Penkrot et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2022), enabling the characterization of sedimentary units and providing information about their provenance and depositional processes. As a result, XRF data are useful for paleoceanographic reconstruction and interpretation (Croudace and Rothwell, 2015). Site U1609 sediment was scanned at a 4–5 cm resolution from ~202 m to 509 m CSF-A, comprising Holes U1609A (Cores 23H–63X) and U1609B (Cores 26F–61X) and corresponding to ~4.52 to ~7.8 Ma in age. The elemental measurements contribute to a more accurate lithologic description and analysis because it shows the sediments’ elemental composition not visible to the naked eye. This improves the potential for correlation between Holes U1609A and U1609B and other sites that track the evolving Miocene Mediterranean outflow.

2. Methods and materials

XRF scanning was performed on cores for Holes U1609A and U1609B at the IODP Gulf Coast Repository at Texas A&M University (USA). The analyses for Holes U1609A and U1609B were performed on the split surface of archive section halves using a third-generation Avaatech XRF core scanner (XRF 1), which operates with a water-cooled, 100 W rhodium side-window X-ray tube, a Brightspec SiriusSD silicon drift detector, and a Topaz-X high-resolution digital multichannel analyzer (https://www.avaatech.com). This core scanner reliably measures different elements on the periodic table from Al to Ba.

The archive-half sections of Cores 401-U1609A-23H through 63X and 401-U1609B-26F through 61X were scanned with 4–5 cm spacing and occasional shifts in position to avoid small defects on the core surface such as clasts or cracks and depressions. Scanning was performed at three different excitation levels (10, 30, and 50 kV). The 10 kV scan (6 s count time; no filter) measured major and minor elements (e.g., Al, Si, P, Cl, K, Ca, Ti, Mn, Fe, and Cr). The 30 kV scan (6 s count time; with a thick Pd filter) measured trace elements with geologic relevance (Amadori et al., 2024), including K, Ca, Ti, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn, Br, Rb, Sr, and Zr. For the 50 kV scan (10 s count time; with a Cu filter), the elements measured were Sr, Rb, Zr, and Ba. The crosscore and downcore slits were set to 12 and 10 mm, respectively. The current was set to 0.16, 1.25, and 0.75 mA for the 10, 30, and 50 kV scans, respectively.

Several elements are plotted in this report: Al, Si, Ca, Ti, Mn, and Fe were analyzed at 10 kV; Rb, Sr, and Zr were analyzed at 30 kV; and Ba was analyzed at 50 kV (Table T1). Measured area counts per second of the spectral peaks of each element were converted to logarithmic elemental ratios.

2.1. Sediment core preparation

After being stored in the refrigerated core repository at 4°C, the section halves were thermally equilibrated to room temperature. A thin layer of sediment was removed by carefully scraping each section with a glass slide, parallel to bedding, to remove mold and other impurities and smooth the section surface. This ensures an even surface and consistent contact with the detector. The section halves were then carefully covered with a 4 µm thick Ultralene film to prevent contamination of the XRF measuring detector. Attention was also given to the central zone of each core section to prevent air pockets from forming between the sediment and film. Thermal equilibration before covering the sediment with film prevents condensation. This is important because water condensed on the film can absorb X-rays, resulting in bias against light element measurements (Kido et al., 2006; Tjallingii et al., 2007; Bertrand et al., 2015).

2.2. Sample selection

XRF elemental scanning at a 4–5 cm resolution was carried out at ~202–502 m CSF-A in Hole U1609A and ~205–509 m CSF-A in Hole U1609B to obtain records for the Messinian (7.25–5.33 Ma) and most of the Zanclean (5.33–4.52 Ma). Within each ~1.5 m core section, the first point to be scanned was 4 or 5 cm below the top of the section and the last was as close as possible to the bottom of the section. For planning the exact points scanned with the XRF detector, a 3D-printed replica of the scanning window was used to examine each core to avoid section voids (due to drilling disturbance, for example), cracks from water loss, rough surfaces, or intervals affected by intense biscuiting. Because of lithologic changes and stiffness increasing with depth, the extended core barrel (XCB) drilling system was used below 270 m CSF-A in Hole U1609A and below 240 m CSF-A in Hole U1609B. XCB coring causes a characteristic increase in the drilling disturbance, termed biscuiting. In these cores, care was taken to avoid the soft, ground-up sediment, termed gravy, between the biscuits, as recommended by Lowery et al. (2024). In this case, the XRF sample spots were moved a few centimeters to the closest firm sediment.

2.3. Quality control

To ensure consistent data, daily quality control was performed during XRF data acquisition by running standards at the three excitation levels (10, 30, and 50 kV) used for elemental data acquisition. Before starting to measure and warm up the scanner, 20 replicates per excitation level were run. These standard data were compared with a single standard run for each voltage after finishing scanning for the day to assess instrument performance and check for any contamination on the film. Raw spectral peaks were processed into peak areas and exported as counts per second using the Brightspec XRF spectral processing software bAxil. Quality control of the data included the removal of bad measurements resulting from gaps between the sensor and the core, as well as the exclusion of sample points <150,000 counts/s on the 10 kV scan or with a positive Ar value, which indicated the detector was measuring ambient air. Additionally, elemental values within two standard deviations of zero should be deleted from XRF data sets (Amadori et al., 2024). However, data points were not removed based on this criterion because those values may be quite variable from element to element in a single sample (e.g., Ti counts may be significant, whereas Ni counts may not be). The end user of the data is left with the choice to delete these data points or not.

3. Results

3.1. Correlation between elements

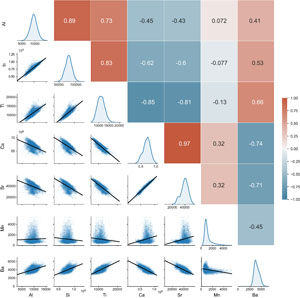

Crossplots reveal strong positive correlations between terrigenous-derived major elements Al, Si, and Ti (Figure F2). A Spearman’s rank correlation for these elements determines the degree and direction of correlation where the data are not normally distributed (Figure F2).

Figure F2. Crossplots, kernel density estimation plots for elements, and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between elements.

Biogenic elements (Ca and Sr) are also strongly positively correlated but have negative correlations with the terrigenous elements Al, Si, and Ti, as well as with Ba. Ba correlates positively with terrigenous elements and negatively with biogenic ones (Figure F2). Although Ba can be related to export productivity (e.g., Carter et al., 2020; Lowery and Bralower, 2022) associated with paleoproductivity (Eagle and Paytan, 2003; Gonneea and Paytan, 2006), at Site U1609 it is positively correlated with the terrigenous elements (Figures F3, F4). It therefore appears to be dominated by terrigenous contributions, as in the European Nordic Seas (Pirrung et al., 2008). According to Hsieh and Henderson (2017), the marine barium cycle is not directly associated with either the silica or carbonate cycle. At high sulfate concentrations, Ba is deposited as a highly insoluble element that can dissolve and diffuse up and down below the sulfate reduction zone (e.g., Phillips et al., 2001). Mn, although mostly associated with terrigenous sources, is exceptional in correlating positively with biogenic Ca and Sr and negatively with the other terrigenous elements (Figure F2), although all Mn correlations are significantly weaker than those of the other elements. The alternations between relatively terrigenous and biogenic sediments, as described on board, are reflected in the XRF measurements.

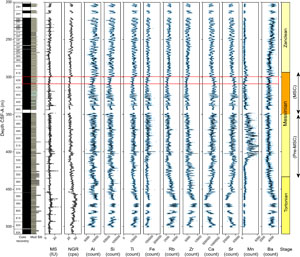

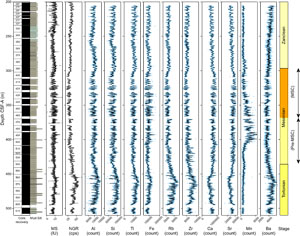

3.2. Stratigraphic trends

XRF data scanning provides a high-resolution record of Site U1609 sedimentary geochemistry. The overall stratigraphic evolution of the terrigenous elements parallels the broad pattern of the natural gamma radiation (NGR) data (Figures F3, F4). For example, from ~500 to ~445 m CSF-A, both NGR and terrigenous elements increase during the Tortonian, although the XRF data typically have more variability than the NGR. Although the sequence is dominated by cyclicity, there is a distinct change in the characteristic amplitude and wavelengths with thinner, lower variability cycles at the base of both Holes U1609A and U1609B and thicker, higher amplitude cycles at the top (Figures F3, F4). Biogenic elements are consistently out of phase with the terrestrial elements, NGR, and magnetic susceptibility (MS), as expected.

At the end of the Messinian (~320–300 m CSF-A; Cores 401-U1609A-41X through 43X and 401-U1609B-39X through 41X) (red rectangle on Figures F3 and F4), the amplitude of cyclicity is minimal with smooth peaks and troughs. During this interval, terrigenous elements and NGR values are among the lowest of the whole record and biogenic values are among the highest.

3.3. Data availability

Expedition 401 data (Flecker et al., 2025) are available at Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/communities/iodp).

4. Acknowledgments

This research used samples provided by IODP. We are grateful for the assistance of the crew and technicians on board JOIDES Resolution for Expedition 401, as well as the technicians at the Gulf Coast Repository, including Kara Vadman. The National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the XRF scans reported here, which comprise the programmatic scanning for Expedition 401, in agreement with the US Science Support Program (USSSP), including funding for travel support for US scientists administered by USSSP. Manuel Teixeira thanks IODP for funding his participation on Expedition 401, and the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia [FCT]) for postcruise funding and travel support. This work was funded by the FCT I.P./MCTES UID/PRR/50019/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/50019/2025). This research was supported by a postcruise activity award from the IODP USSSP (NSF prime award OCE-1450528). We acknowledge the reviewer Dr. Christopher Lowery for constructive comments and suggestions, which greatly improved this work.

References

Amadori, C., Borrelli, C., Christeson, G., Estes, E., Guertin, L., Hertzberg, J., Kaplan, M.R., Koorapati, R.K., Lam, A.R., Lowery, C.M., McIntyre, A., Reece, J., Robustelli Test, C., Routledge, C.M., Standring, P., Sylvan, J.B., Thompson, M., Villa, A., Wang, Y., Wee, S.Y., Williams, T., Yeon, J., Teagle, D.A.H., Coggon, R.M., and the Expedition 390/393 Scientists, 2024. Data report: X-ray fluorescence scanning of sediment cores, IODP Expedition 390/393 Site U1560, South Atlantic Transect. In Coggon, R.M., Teagle, D.A.H., Sylvan, J.B., Reece, J., Estes, E.R., Williams, T.J., Christeson, G.L., and the Expedition 390/393 Scientists, South Atlantic Transect. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 390/393: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.390393.205.2024

Bertrand, S., Hughen, K., and Giosan, L., 2015. Limited Influence of Sediment Grain Size on Elemental XRF Core Scanner Measurements. In Croudace, I.W. and Rothwell, R.G., Micro-XRF Studies of Sediment Cores: Applications of a non-destructive tool for the environmental sciences. Dordrecht (Springer Netherlands), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9849-5_19

Bulian, F., Jiménez-Espejo, F.J., Andersen, N., Larrasoaña, J.C., and Sierro, F.J., 2023. Mediterranean water in the Atlantic Iberian margin reveals early isolation events during the Messinian Salinity Crisis. Global and Planetary Change, 231:104297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104297

Capella, W., Barhoun, N., Flecker, R., Hilgen, F.J., Kouwenhoven, T., Matenco, L.C., Sierro, F.J., Tulbure, M.A., Yousfi, M.Z., and Krijgsman, W., 2018. Palaeogeographic evolution of the late Miocene Rifian Corridor (Morocco): reconstructions from surface and subsurface data. Earth-Science Reviews, 180:37–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.02.017

Capella, W., Hernández-Molina, F.J., Flecker, R., Hilgen, F.J., Hssain, M., Kouwenhoven, T.J., van Oorschot, M., Sierro, F.J., Stow, D.A.V., Trabucho-Alexandre, J., Tulbure, M.A., de Weger, W., Yousfi, M.Z., and Krijgsman, W., 2017. Sandy contourite drift in the late Miocene Rifian Corridor (Morocco): reconstruction of depositional environments in a foreland-basin seaway. Sedimentary Geology, 355:31–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2017.04.004

Carter, S.C., Paytan, A., and Griffith, E.M., 2020. Toward an improved understanding of the marine barium cycle and the application of marine barite as a paleoproductivity proxy. Minerals, 10(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/min10050421

Croudace, I.W., and Rothwell, R.G. (Eds.), 2015. Micro-XRF Studies of Sediment Cores: Applications of a Non-destructive Tool for the Environmental Sciences: Dordrecht, Netherlands (Springer). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9849-5

Eagle, M., Paytan, A., Arrigo, K.R., van Dijken, G., and Murray, R.W., 2003. A comparison between excess barium and barite as indicators of carbon export. Paleoceanography, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1029/2002PA000793

Expedition 339 Scientists, 2013. Expedition 339 summary. In Stow, D.A.V., Hernández-Molina, F.J., Alvarez Zarikian, C.A., and the Expedition 339 Scientists, Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, 339: Tokyo (Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Management International, Inc.). https://doi.org/10.2204/iodp.proc.339.101.2013

Flecker, R., Ducassou, E., Williams, T., Amarathunga, U., Balestra, B., Berke, M.A., Blättler, C.L., Chin, S., Das, M., Egawa, K., Fabregas, N., Feakins, S.J., George, S.C., Hernández-Molina, F.J., Krijgsman, W., Li, Z., Liu, J., Noto, D., Raad, F., Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J., Sierro, F.J., Standring, P., Stine, J., Tanaka, E., Teixeira, M., Xu, X., Yin, S., and Yousfi, M.Z., 2025. IODP Expedition 401 X-ray fluorescence (XRF) [Data set]. International Ocean Discovery Program. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16459854

Flecker, R., Krijgsman, W., Capella, W., de Castro Martíns, C., Dmitrieva, E., Mayser, J.P., Marzocchi, A., Modestou, S., Ochoa, D., Simon, D., Tulbure, M., van den Berg, B., van der Schee, M., de Lange, G., Ellam, R., Govers, R., Gutjahr, M., Hilgen, F., Kouwenhoven, T., Lofi, J., Meijer, P., Sierro, F.J., Bachiri, N., Barhoun, N., Alami, A.C., Chacon, B., Flores, J.A., Gregory, J., Howard, J., Lunt, D., Ochoa, M., Pancost, R., Vincent, S., and Yousfi, M.Z., 2015. Evolution of the Late Miocene Mediterranean–Atlantic gateways and their impact on regional and global environmental change. Earth-Science Reviews, 150:365–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.08.007

Garcia-Castellanos, D., Estrada, F., Jiménez-Munt, I., Gorini, C., Fernàndez, M., Vergés, J., and De Vicente, R., 2009. Catastrophic flood of the Mediterranean after the Messinian salinity crisis. Nature, 462(7274):778–781. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08555

Garcia-Castellanos, D., and Villaseñor, A., 2011. Messinian salinity crisis regulated by competing tectonics and erosion at the Gibraltar arc. Nature, 480(7377):359–363. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10651

Gonneea, M.E., and Paytan, A., 2006. Phase associations of barium in marine sediments. Marine Chemistry, 100(1):124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2005.12.003

Hernández-Molina, J., Llave, E., Somoza, L., Fernández-Puga, M.C., Maestro, A., León, R., Medialdea, T., Barnolas, A., García, M., Díaz del Río, V., Fernández-Salas, L.M., Vázquez, J.T., Lobo, F., Alveirinho Dias, J.M., Rodero, J., and Gardner, J., 2003. Looking for clues to paleoceanographic imprints: a diagnosis of the Gulf of Cadiz contourite depositional systems. Geology, 31(1):19–22. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031%3C0019:LFCTPI%3E2.0.CO;2

Hernández-Molina, F.J., Serra, N., Stow, D.A.V., Llave, E., Ercilla, G., and Van Rooij, D., 2011. Along-slope oceanographic processes and sedimentary products around the Iberian margin. Geo-Marine Letters, 31(5):315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-011-0242-2

Hernández-Molina, F.J., Sierro, F.J., Llave, E., Roque, C., Stow, D.A.V., Williams, T., Lofi, J., Van der Schee, M., Arnáiz, A., Ledesma, S., Rosales, C., Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J., Pardo-Igúzquiza, E., and Brackenridge, R.E., 2016. Evolution of the Gulf of Cadiz margin and southwest Portugal contourite depositional system: tectonic, sedimentary and paleoceanographic implications from IODP Expedition 339. Marine Geology, 377:7–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.09.013

Hernández-Molina, F.J., Stow, D.A.V., Alvarez-Zarikian, C.A., Acton, G., Bahr, A., Balestra, B., Ducassou, E., Flood, R., Flores, J.-A., Furota, S., Grunert, P., Hodell, D., Jimenez-Espejo, F., Kim, J.K., Krissek, L., Kuroda, J., Li, B., Llave, E., Lofi, J., Lourens, L., Miller, M., Nanayama, F., Nishida, N., Richter, C., Roque, C., Pereira, H., Sanchez Goñi, M.F., Sierro, F.J., Singh, A.D., Sloss, C., Takashimizu, Y., Tzanova, A., Voelker, A., Williams, T., and Xuan, C., 2014. Onset of Mediterranean outflow into the North Atlantic. Science, 344(6189):1244–1250. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1251306

Hsieh, Y.-T., and Henderson, G.M., 2017. Barium stable isotopes in the global ocean: Tracer of Ba inputs and utilization. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 473:269–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.06.024

Hsü, K.J., Ryan, W.B.F., and Cita, M.B., 1973. Late Miocene desiccation of the Mediterranean. Nature, 242(5395):240–244. https://doi.org/10.1038/242240a0

Kido, Y., Koshikawa, T., and Tada, R., 2006. Rapid and quantitative major element analysis method for wet fine-grained sediments using an XRF microscanner. Marine Geology, 229(3–4):209–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2006.03.002

Krijgsman, W., Capella, W., Simon, D., Hilgen, F.J., Kouwenhoven, T.J., Meijer, P.T., Sierro, F.J., Tulbure, M.A., van den Berg, B.C.J., van der Schee, M., and Flecker, R., 2018. The Gibraltar Corridor: Watergate of the Messinian Salinity Crisis. Marine Geology, 403:238–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2018.06.008

Krijgsman, W., Hilgen, F.J., Langereis, C.G., and Zachariasse, W.J., 1994. The age of the Tortonian/Messinian boundary. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 121(3):533–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(94)90089-2

Krijgsman, W., Hilgen, F.J., Raffi, I., Sierro, F.J., and Wilson, D.S., 1999a. Chronology, causes and progression of the Messinian salinity crisis. Nature, 400(6745):652–655. https://doi.org/10.1038/23231

Krijgsman, W., and Langereis, C.G., 2000. Magnetostratigraphy of the Zobzit and Koudiat Zarga sections (Taza-Guercif basin, Morocco): implications for the evolution of the Rifian Corridor. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 17(3):359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8172(99)00029-X

Krijgsman, W., Langereis, C.G., Zachariasse, W.J., Boccaletti, M., Moratti, G., Gelati, R., Iaccarino, S., Papani, G., and Villa, G., 1999b. Late Neogene evolution of the Taza–Guercif Basin (Rifian Corridor, Morocco) and implications for the Messinian salinity crisis. Marine Geology, 153(1):147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00084-X

Krijgsman, W., Rohling, E.J., Palcu, D.V., Raad, F., Amarathunga, U., Flecker, R., Florindo, F., Roberts, A.P., Sierro, F.J., and Aloisi, G., 2024. Causes and consequences of the Messinian salinity crisis. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 5(5):335–350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-024-00533-1

Lowery, C.M., Amadori, C., Borrelli, C., Christeson, G., Estes, E., Guertin, L., Hertzberg, J., Kaplan, M.R., Koorapati, R.K., Lam, A.R., McIntyre, A., Reece, J., Robustelli Test, C., Routledge, C.M., Standring, P., Sylvan, J.B., Thompson, M., Villa, A., Wang, Y., Wee, S.Y., Williams, T., Yeon, J., Teagle, D.A.H., Coggon, R.M., and the Expedition 390/393 Scientists, 2024. Data report: X-ray fluorescence scanning of sediment cores, IODP Expedition 390/393 Site U1557, South Atlantic Transect. In Coggon, R.M., Teagle, D.A.H., Sylvan, J.B., Reece, J., Estes, E.R., Williams, T.J., Christeson, G.L., and the Expedition 390/393 Scientists, South Atlantic Transect. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 390/393: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.390393.201.2024

Lowery, C.M., and Bralower, T.J., 2022. Elevated post K-Pg export productivity in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 37(9):e2021PA004400. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021PA004400

Maldonado, A., Somoza, L.s., and Pallarés, L., 1999. The Betic orogen and the Iberian–African boundary in the Gulf of Cadiz: geological evolution (central North Atlantic). Marine Geology, 155(1):9–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00139-X

Martínez del Olmo, W., and Martín, D., 2016. El Neógeno de la cuenca Guadalquivir-Cádiz (Sur de España). Revista de la Sociedad Geológica de España, 29(1):35–58.

Penkrot, M.L., Jaeger, J.M., Cowan, E.A., St-Onge, G., and LeVay, L., 2018. Multivariate modeling of glacimarine lithostratigraphy combining scanning XRF, multisensory core properties, and CT imagery: IODP Site U1419. Geosphere, 14(4):1935–1960. https://doi.org/10.1130/GES01635.1

Phillips, E.J.P., Landa, E.R., Kraemer, T., and Zielinski, R., 2001. Sulfate-reducing bacteria release barium and radium from naturally occurring radioactive material in oil-field barite. Geomicrobiology Journal, 18(2):167–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490450120549

Pirrung, M., Illner, P., and Matthiessen, J., 2008. Biogenic barium in surface sediments of the European Nordic Seas. Marine Geology, 250(1):89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2008.01.001

Popov, S.V., Shcherba, I.G., Ilyina, L.B., Nevesskaya, L.A., Paramonova, N.P., Khondkarian, S.O., and Magyar, I., 2006. Late Miocene to Pliocene palaeogeography of the Paratethys and its relation to the Mediterranean. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 238(1):91–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.03.020

Riaza, C., and Martínez Del Olmo, W., 1996. Depositional model of the Guadalquivir – Gulf of Cadiz Tertiary basin. In Friend, P.F. and Dabrio, C.J., Tertiary Basins of Spain: The Stratigraphic Record of Crustal Kinematics. Cambridge (Cambridge University Press), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511524851.047

Rodrigues, S., Roque, C., Hernández-Molina, F.J., Llave, E., and Terrinha, P., 2020. The sines contourite depositional system along the SW Portuguese margin: onset, evolution and conceptual implications. Marine Geology, 430:106357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2020.106357

Rogerson, M., Rohling, E.J., Weaver, P.P.E., and Murray, J.W., 2005. Glacial to interglacial changes in the settling depth of the Mediterranean Outflow plume. Paleoceanography, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.1029/2004PA001106

Roveri, M., Flecker, R., Krijgsman, W., Lofi, J., Lugli, S., Manzi, V., Sierro, F.J., Bertini, A., Camerlenghi, A., De Lange, G., Govers, R., Hilgen, F.J., Hübscher, C., Meijer, P.T., and Stoica, M., 2014. The Messinian salinity crisis: past and future of a great challenge for marine sciences. Marine Geology, 352:25–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2014.02.002

Schönfeld, J., and Zahn, R., 2000. Late Glacial to Holocene history of the Mediterranean Outflow. Evidence from benthic foraminiferal assemblages and stable isotopes at the Portuguese margin. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 159(1–2):85–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00035-3

Sierro, F.J., Delgado, J.A.G., Dabrio, C.J., Flores, J.A., and Civis, J., 1996. Late Neogene depositional sequences in the foreland basin of Guadalquivir (SW Spain). In Friend, P.F. and Dabrio, C.J., Tertiary Basins of Spain: The Stratigraphic Record of Crustal Kinematics. Cambridge (Cambridge University Press), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511524851.048

Taylor, S.P., Patterson, M.O., Lam, A.R., Jones, H., Woodard, S.C., Habicht, M.H., Thomas, E.K., and Grant, G.R., 2022. Expanded North Pacific subtropical gyre and heterodyne expression during the Mid-Pleistocene. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 37(5):e2021PA004395. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021PA004395

Teixeira, M., Roque, C., Omira, R., Marques, F., Gamboa, D., Terrinha, P., Ercilla, G., Yenes, M., Mena, A., and Casas, D., 2024. Submarine landslide hazard in the Sines Contourite Drift, SW Iberia: slope instability analysis under static and transient conditions. Natural Hazards, 120(4):3505–3531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06340-z

Teixeira, M., Terrinha, P., Roque, C., Rosa, M., Ercilla, G., and Casas, D., 2019. Interaction of alongslope and downslope processes in the Alentejo Margin (SW Iberia) – implications on slope stability. Marine Geology, 410:88–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2018.12.011

Teixeira, M., Terrinha, P., Roque, C., Voelker, A.H.L., Silva, P., Salgueiro, E., Abrantes, F., Naughton, F., Mena, A., Ercilla, G., and Casas, D., 2020. The Late Pleistocene-Holocene sedimentary evolution of the Sines Contourite Drift (SW Portuguese Margin): A multiproxy approach. Sedimentary Geology, 407:105737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2020.105737

Teixeira, M., Viana da Fonseca, A., Cordeiro, D., Terrinha, P., and Roque, C., 2022. Geotechnical properties of Sines Contourite Drift sediments: their contribution to submarine landslide susceptibility. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 81(9). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-022-02873-y

Tjallingii, R., Röhl, U., Kölling, M., and Bickert, T., 2007. Influence of the water content on X-ray fluorescence core-scanning measurements in soft marine sediments. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 8(2):Q02004. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GC001393

Toucanne, S., Mulder, T., Schönfeld, J., Hanquiez, V., Gonthier, E., Duprat, J., Cremer, M., and Zaragosi, S., 2007. Contourites of the Gulf of Cadiz: A high-resolution record of the paleocirculation of the Mediterranean outflow water during the last 50,000 years. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 246(2):354–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.10.007

Voelker, A.H.L., Lebreiro, S.M., Schönfeld, J., Cacho, I., Erlenkeuser, H., and Abrantes, F., 2006. Mediterranean outflow strengthening during northern hemisphere coolings: a salt source for the glacial Atlantic? Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 245(1):39–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2006.03.014