Sutherland, R., Dickens, G.R., Blum, P., and the Expedition 371 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 371

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.371.201.2024

Data report: Middle Miocene to earliest Pleistocene Trilobatus sacculifer stable isotopic records, IODP Expedition 371 Site U1506, Tasman Sea1

Adriane R. Lam,2 Jeanette deCuba,2 Gretl King,2 and Ravi Kiran Koorapati2

1 Lam, A.R., deCuba, J., King, G., and Koorapati, R.K., 2024. Data report: Middle Miocene to earliest Pleistocene Trilobatus sacculifer stable isotopic records, IODP Expedition 371 Site U1506, Tasman Sea. In Sutherland, R., Dickens, G.R., Blum, P., and the Expedition 371 Scientists, Tasman Frontier Subduction Initiation and Paleogene Climate. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 371: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.371.201.2024

2 Earth Sciences Department, Binghamton University, USA. Correspondence author: alam@binghamton.edu

Abstract

The Late Neogene to Quaternary periods include several climate and tectonic events that brought the surface ocean circulation system into its modern configuration. Characterizing how surface conditions, namely temperature and salinity gradients, behaved in response to cooling and warming events has implications for understanding past atmospheric and biotic processes and how the Earth system may respond to increased anthropogenic warming. One region that lacks long-term geochemical records is the Tasman Sea, southwest Pacific Ocean. This region is characterized by a major western boundary current and its extensional flow, which creates large temperature gradients within the basin. Prior geochemical analyses indicate this region warmed and cooled in response to tectonic gateway closures. To build on these geochemical data sets and create a transect across the northern Tasman Sea, we use δ18O and δ13C measurements from the mixed-layer planktic foraminifera species Trilobatus sacculifer to reconstruct surface ocean conditions from the Middle Miocene to early Pleistocene (12–2.3 Ma) at International Ocean Discovery Program Site U1506. We find that surface ocean conditions at the site oscillated through time, with some major stepped changes in the isotopic values through the Miocene. Additional geochemical time series developed in the future from more central and southern Tasman Sea sites will aid in understanding the development and behavior of such frontal boundary systems through the Neogene.

1. Introduction

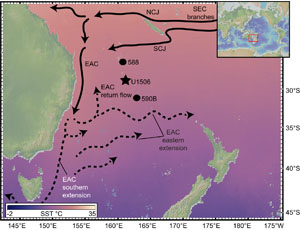

The Late Neogene to Early Quaternary periods (~12–2.3 Ma) are a time of overall global cooling punctuated by climatic shifts and tectonic gateway reconfigurations (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Westerhold et al., 2020). These events include the constriction of the Indonesian Throughflow through the Neogene (reviewed in Kuhnt et al., 2004); the continued and stepwise cooling of southern high latitudes (~14.6–9.0 Ma; Holbourn et al., 2013); the constriction and closure of the Central American Seaway (critical threshold of closure ~4.8–4 Ma; Haug and Tiedemann, 1998; Steph et al., 2010); the mid-Piacenzian Warm Period (3.2–2.9 Ma; e.g., Raymo et al., 1996; Pagani et al., 2010; Martínez-Botí et al., 2015; O’Dea et al., 2016); and the initiation and growth of Northern Hemisphere glaciers (~3.6–2.4 Ma; Mudelsee and Raymo, 2005). These major Earth events led to the surface ocean circulation system and sea surface temperature gradients that characterize today’s ocean, especially in the midlatitudes (e.g., Lam et al., 2020, 2021; Sutherland et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2023). Understanding how the surface ocean and temperature gradients responded to such tectonic and climate changes and how they came into their modern configuration has implications for understanding the ocean systems’ influence on atmospheric and biotic processes and how such systems may behave in the future under anthropogenic warming scenarios. The Tasman Sea in the southwest Pacific Ocean, an area dominated by a wide and drastic sea surface temperature gradient, is one region in which we can study the effects of changing climate and tectonic gateway closures on the surface ocean (Figure F1).

The South Pacific Tasman Sea surface ocean circulation system is dominated by the Eastern Australia Current (EAC), the major western boundary current of the South Pacific Gyre system that transports heat and moisture (e.g., Sprintall et al., 1995), and it influences both regional weather (Sprintall et al., 1995) and climate patterns (e.g., Cai et al., 2005). This current flows along the east coast of Australia, where it detaches from the coast between 30° and 34°S and flows eastward. An allotment of the EAC continues southward, around Tasmania (Figure F1). This portion of the current that flows eastward has traditionally been termed the Tasman Front, but recent publications indicate the eastward flow features are only apparent in time-averaged data (Oke et al., 2019a). Instead, where the EAC separates from the Australian coast, there is a complex field of eddies that feed flow from the Australian coast toward New Zealand (Oke et al., 2019a). Oke et al. (2019b) showed the Tasman Front is not a true frontal system and instead suggested calling the area the “EAC southern extension,” a term we have adopted here.

Oceanic frontal systems, such as the EAC southern extension, and sea surface temperature gradients in the Tasman Sea developed as a response to the opening of the Drake Passage and growth of Antarctic ice sheets during the Oligocene, leading to the establishment and intensification of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (Nelson and Cooke, 2001; Pfuhl and McCave, 2005). Despite these findings, few long-term geochemical records have been published from the Tasman Sea to infer how the EAC southern extension responded to tectonic and climate events through the Neogene. Recently, Gastaldello et al. (2023) used stable isotopic analyses and benthic foraminiferal assemblages from International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 371 to characterize the Middle Miocene Biogenic Bloom in the Tasman Sea. They found that the event was complex with multiple phases. Karas et al. (2011) developed a paired δ18O and Mg/Ca record from the planktonic foraminifera species Trilobatus sacculifer for Deep Sea Drilling Program (DSDP) Hole 590B (31.17°S, 163.49°E; Figure F1). Their data indicate the northern Tasman Sea experienced surface water cooling and freshening in response to the closure of the Central American Seaway. Warming of the northern Tasman Sea after ~3.8 Ma was triggered by a constricting Indonesian Throughflow and intensification of the EAC (Karas et al., 2011). Hodell and Kennett (1986) created a stable isotopic curve for DSDP Site 588 (26.29°S, 161.38°E; Figure F1), located north of Hole 590B. Here, there is less variability in the δ18O signal, but their data also indicate cooling and/or freshening around ~4 Ma associated with the constriction of the Central American Seaway, followed by surface water warming.

To better infer the behavior of the surface ocean conditions through time in the Tasman Sea, we have created a long-term stable isotopic time series (δ18O and δ13C) at a site located between Site 588 and Hole 590B. We used the mixed-layer planktonic foraminiferal species T. sacculifer (Keller and Kennett, 1985) from IODP Site U1506 to construct a record from the Middle Miocene to earliest Pleistocene (~12–2.33 Ma). Our results indicate that at Site U1506, sea surface conditions were variable throughout the study interval, likely as a result of tectonic gateway closures and climate shifts.

2. Materials and methods

A low-resolution (approximately one sample every ~49 ky) mixed-layer stable isotope record was constructed for Site U1506 (28.66°S, 161.74°E; 1494.9 m water depth). For this analysis, 195 10 cm3 bulk sediment samples were dried in an oven at 50°C for approximately 48 h. Bulk samples were weighed and then washed over a 63 μm screen with tap water. Sieved >63 μm residues were then transferred to an oven to dry at 50°C overnight. Once dry, the residues were weighed, vialed, and labeled.

To produce the stable isotopic (δ18O and δ13C) record for subtropical Site U1506, we picked four to six specimens of T. sacculifer (without the elongate sac-like final chamber) from each sample from the 355–425 μm size fraction (see ISOTOPE in Supplementary material). We conducted replicates on 12 of the samples used in the study as an a priori test on within-sample variability (Table T1). Isotopic results are reported against Vienna Peedee Belemnite (VPDB) using the standard δ notation expressed in permil (‰). Stable isotopic measurements were made on a Finnigan Delta Plus XL ratio mass spectrometer coupled with a GasBench II automated sampler at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Analytical precision was better than 0.08‰ for δ18O and 0.06‰ for δ13C (one standard deviation) based on tracking of uncorrected results for an in-house standard for Site U1506 samples.

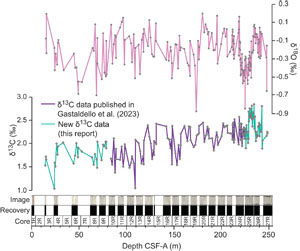

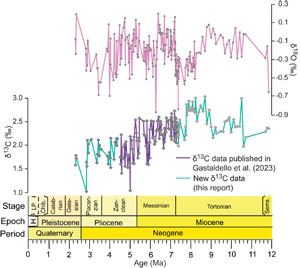

Measurements were plotted against depth in the core (Figure F2) and on the age model developed using calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy for Site U1506 (Sutherland et al., 2019), including the tuned age model for part of the section from Gastaldello et al. (2023) (Figure F3).

3. Results

3.1. Within-sample variability

A total of 12 replicate samples from Site U1506, representing 6% of the total samples, were run to determine within-sample variability (Table T1). Intrasample variability (difference within samples) for δ13C values ranges 0.05‰–0.41‰, and δ18O sample variability ranges 0.00‰–0.47‰.

3.1.1. Stable isotopic measurements

Throughout the study interval, sea surface temperature and/or salinity changed drastically (Figures F2, F3). From 12 to ~10.6 Ma, δ18O values quickly increase, whereas δ13C values remain steady around 2.25‰ but exhibit a slight decrease. From ~10.6 to ~8.5 Ma, δ18O values remain largely steady within the range of ~0.3‰–0.1‰. In the same interval, δ13C values exhibit a general decrease, generally around ~2.5‰, with intermittent increases to ~3.0‰ at ~10.5 and 8.8 Ma. The late Tortonian is characterized by decreasing δ18O values, from 0.1‰ at ~8.8 Ma to −0.6‰ at ~7.2 Ma. Carbon isotope values exhibit a decrease from about 2.5‰ at ~8.8 Ma to ~2.0‰ at ~7.2 Ma. The Late Miocene Messinian Stage is characterized by δ18O values that increase and oscillate within the range of about −0.3‰ to 0.1‰ until 6.2 Ma. Within the same time interval (7.2–6.2 Ma), δ13C values oscillate between ~2.5‰ and 2.0‰. The latest Miocene (6.2–5.3 Ma) is characterized by another step decline in the δ18O record, with values decreasing and oscillating between approximately −0.5‰ and −0.1‰ and δ13C values oscillating around 2.5‰–1.6‰.

The stable isotopic records within the Pliocene are generally less variable than the Miocene, with no large and apparent stepwise increases or decreases in stable isotopic values. Generally, the δ18O values from the Early Pliocene to earliest Pleistocene range approximately −0.7‰–0.3‰, and the δ13C values range 2.5‰–1.0‰.

Because these samples are from a midlatitude site, seasonality has likely greatly influenced the stable isotopic values obtained from surface-dwelling planktonic foraminifera (e.g., Lam et al., 2021). Therefore, such abiotic factors should be considered when interpreting geochemical records such as those presented in this data report.

4. Acknowledgments

Samples were provided by the International Ocean Discovery Program. We wish to thank all the scientists, staff, and crew who sailed aboard the R/V JOIDES Resolution during Expedition 371. We wish to thank Adam Woodhouse for edits and comments that greatly improved this data report.

References

Cai, W., Shi, G., Cowan, T., Bi, D., and Ribbe, J., 2005. The response of the Southern Annular Mode, the East Australian Current, and the southern mid-latitude ocean circulation to global warming. Geophysical Research Letters, 32(23). https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL024701

Gastaldello, M.E., Agnini, C., Westerhold, T., Drury, A.J., Sutherland, R., Drake, M.K., Lam, A.R., Dickens, G.R., Dallanave, E., Burns, S., and Alegret, L., 2023. The Late Miocene-Early Pliocene biogenic bloom: an integrated study in the Tasman Sea. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 38(4):e2022PA004565. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022PA004565

Haug, G.H., and Tiedemann, R., 1998. Effect of the formation of the Isthmus of Panama on Atlantic Ocean thermohaline circulation. Nature, 393(6686):673–676. https://doi.org/10.1038/31447

Hodell, D.A., and Kennett, J.P., 1986. Late Miocene–Early Pliocene stratigraphy and paleoceanography of the South Atlantic and southwest Pacific oceans: a synthesis. Paleoceanography, 1(3):285–311. https://doi.org/10.1029/PA001i003p00285

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Clemens, S., Prell, W., and Andersen, N., 2013. Middle to Late Miocene stepwise climate cooling: evidence from a high-resolution deep water isotope curve spanning 8 million years. Paleoceanography, 28(4):688–699. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013PA002538

Karas, C., Nürnberg, D., Tiedemann, R., and Garbe-Schõnberg, D., 2011. Pliocene climate change of the Southwest Pacific and the impact of ocean gateways. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 301(1–2):117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.10.028

Keller, G., and Kennett, J.P., 1985. Depth stratification of planktonic foraminifers in the Miocene ocean. In Kennett, J.P., The Miocene Ocean: Paleoceanography and Biogeography. Memoirs - Geological Society of America, 163. https://doi.org/10.1130/MEM163-p177

Kuhnt, W., Holbourn, A., Hall, R., Zuvela, M., and Käse, R., 2004. Neogene history of the Indonesian throughflow. In Clift, P., Kuhnt, W., Wang, P., and Hayes, D. (Eds.), Continent‐Ocean Interactions Within East Asian Marginal Seas. Geophysical Monograph, 149: 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1029/149GM16

Lam, A.R., deCuba, J., King, G., and Koorapati, R.K., 2024. Supplementary material, https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.371.201supp.2024. In Lam, A.R., deCuba, J., King, Gretl, and Koorapati, R.K., Data report: Middle Miocene to earliest Pleistocene Trilobatus sacculifer stable isotopic records, IODP Expedition 371 Site U1506, Tasman Sea. In Sutherland, R., Dickens, G.R., Blum, P., and the Expedition 371 Scientists, Tasman Frontier Subduction Initiation and Paleogene Climate. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 371: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program).

Lam, A.R., Leckie, R.M., and Patterson, M.O., 2020. Illuminating the past to see the future of western boundary currents: micropaleontological investigations of the Kuroshio Current extension. Oceanography, 33(2):65–67. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2020.219

Lam, A.R., MacLeod, K.G., Schilling, S.H., Leckie, R.M., Fraass, A.J., Patterson, M.O., and Venti, N.L., 2021. Pliocene to Earliest Pleistocene (5–2.5 Ma) reconstruction of the Kuroshio Current extension reveals a dynamic current. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 36(9):e2021PA004318. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021PA004318

Lisiecki, L.E., and Raymo, M.E., 2005. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography, 20(1):PA1003. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004PA001071

Martínez-Botí, M.A., Foster, G.L., Chalk, T.B., Rohling, E.J., Sexton, P.F., Lunt, D.J., Pancost, R.D., Badger, M.P.S., and Schmidt, D.N., 2015. Plio-Pleistocene climate sensitivity evaluated using high-resolution CO2 records. Nature, 518(7537):49–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14145

Mudelsee, M., and Raymo, M.E., 2005. Slow dynamics of the Northern Hemisphere glaciation. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 20(4):PA4022. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005PA001153

Nelson, C.S., and Cooke, P.J., 2001. History of oceanic front development in the New Zealand sector of the Southern Ocean during the Cenozoic—a synthesis. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 44(4):535–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288306.2001.9514954

O’Dea, A., Lessios, H.A., Coates, A.G., Eytan, R.I., Restrepo-Moreno, S.A., Cione, A.L., Collins, L.S., de Queiroz, A., Farris, D.W., Norris, R.D., Stallard, R.F., Woodburne, M.O., Aguilera, O., Aubry, M.-P., Berggren, W.A., Budd, A.F., Cozzuol, M.A., Coppard, S.E., Duque-Caro, H., Finnegan, S., Gasparini, G.M., Grossman, E.L., Johnson, K.G., Keigwin, L.D., Knowlton, N., Leigh, E.G., Leonard-Pingel, J.S., Marko, P.B., Pyenson, N.D., Rachello-Dolmen, P.G., Soibelzon, E., Soibelzon, L., Todd, J.A., Vermeij, G.J., and Jackson, J.B.C., 2016. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Science Advances, 2(8):e1600883. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600883

Oke, P.R., Pilo, G.S., Ridgway, K., Kiss, A., and Rykova, T., 2019a. A search for the Tasman Front. Journal of Marine Systems, 199:103217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2019.103217

Oke, P.R., Roughan, M., Cetina-Heredia, P., Pilo, G.S., Ridgway, K.R., Rykova, T., Archer, M.R., Coleman, R.C., Kerry, C.G., Rocha, C., Schaeffer, A., and Vitarelli, E., 2019b. Revisiting the circulation of the East Australian Current: its path, separation, and eddy field. Progress in Oceanography, 176:102139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2019.102139

Pagani, M., Liu, Z., LaRiviere, J., and Ravelo, A.C., 2010. High Earth-system climate sensitivity determined from Pliocene carbon dioxide concentrations. Nature Geoscience, 3(1):27–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo724

Pfuhl, H.A., and McCave, I.N., 2005. Evidence for late Oligocene establishment of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 235(3–4):715–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.025

Raymo, M.E., Grant, B., Horowitz, M., and Rau, G.H., 1996. Mid-Pliocene warmth: stronger greenhouse and stronger conveyor. Marine Micropaleontology, 27(1–4):313–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(95)00048-8

Singh, V.P., Pathak, S., and Dwivedi, R., 2023. Reduction in the strength of Agulhas Current during Quaternary: planktic foraminiferal records for 1.2 million years from IODP Hole U-1474A. Journal of Climate Change, 9:45–52. https://doi.org/10.3233/JCC230031

Sprintall, J., Roemmich, D., Stanton, B., and Bailey, R., 1995. Regional climate variability and ocean heat transport in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 100(C8):15865–15871. https://doi.org/10.1029/95JC01664

Steph, S., Tiedemann, R., Prange, M., Groeneveld, J., Schulz, M., Timmermann, A., Nürnberg, D., Rühlemann, C., Saukel, C., and Haug, G.H., 2010. Early Pliocene increase in thermohaline overturning: a precondition for the development of the modern equatorial Pacific cold tongue. Paleoceanography, 25(2):PA2202. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001645

Sutherland, R., Dickens, G.R., Blum, P., Agnini, C., Alegret, L., Asatryan, G., Bhattacharya, J., Bordenave, A., Chang, L., Collot, J., Cramwinckel, M.J., Dallanave, E., Drake, M.K., Etienne, S.J.G., Giorgioni, M., Gurnis, M., Harper, D.T., Huang, H.-H.M., Keller, A.L., Lam, A.R., Li, H., Matsui, H., Morgans, H.E.G., Newsam, C., Park, Y.-H., Pascher, K.M., Pekar, S.F., Penman, D.E., Saito, S., Stratford, W.R., Westerhold, T., and Zhou, X., 2019. Site U1506. In Sutherland, R., Dickens, G.R., Blum, P., and the Expedition 371 Scientists, Tasman Frontier Subduction Initiation and Paleogene Climate. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 371: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.371.103.2019

Sutherland, R., Santos, Z.D., Agnini, C., Alegret, L., Lam, A.R., Westerhold, T., Drake, M.K., Harper, D.T., Dallanave, E., Newsam, C., Cramwinkel, M.J., Dickens, G.R., Collot, J., Etienne, S.J.G., Bordenave, A., Stratford, W.R., Zhou, X., Li, H., and Asatryan, G., 2022. Neogene mass accumulation rate of carbonate sediment across northern Zealandia, Tasman Sea, southwest Pacific. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 37(2):e2021PA004294. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021PA004294

Westerhold, T., Marwan, N., Drury, A.J., Liebrand, D., Agnini, C., Anagnostou, E., Barnet, J.S.K., Bohaty, S.M., De Vleeschouwer, D., Florindo, F., Frederichs, T., Hodell, D.A., Holbourn, A.E., Kroon, D., Lauretano, V., Littler, K., Lourens, L.J., Lyle, M., Pälike, H., Röhl, U., Tian, J., Wilkens, R.H., Wilson, P.A., and Zachos, J.C., 2020. An astronomically dated record of Earth’s climate and its predictability over the last 66 million years. Science, 369(6509):1383–1387. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba6853