Knutz, P.C., Jennings, A.E., Childress, L.B., and the Expedition 400 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 400

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.400.103.2025

Site U16031

![]() P.C. Knutz,

P.C. Knutz,

![]() A.E. Jennings,

A.E. Jennings,

![]() L.B. Childress,

L.B. Childress,

![]() R. Bryant,

R. Bryant,

![]() S.K. Cargill,

S.K. Cargill,

![]() H.K. Coxall,

H.K. Coxall,

![]() T.D. Frank,

T.D. Frank,

![]() G.R. Grant,

G.R. Grant,

![]() R.E. Gray,

R.E. Gray,

![]() L. Ives,

L. Ives,

![]() V. Kumar,

V. Kumar,

![]() S. Le Houedec,

S. Le Houedec,

![]() J. Martens,

J. Martens,

![]() F. Naim,

F. Naim,

![]() M. Nelissen,

M. Nelissen,

![]() V. Özen,

V. Özen,

![]() S. Passchier,

S. Passchier,

![]() L.F. Pérez,

L.F. Pérez,

![]() J. Ren,

J. Ren,

![]() B.W. Romans,

B.W. Romans,

![]() O. Seki,

O. Seki,

![]() P. Staudigel,

P. Staudigel,

![]() L. Tauxe,

L. Tauxe,

![]() E.J. Tibbett,

E.J. Tibbett,

![]() Y. Yokoyama,

Y. Yokoyama,

![]() Y. Zhang, and

Y. Zhang, and

![]() H. Zimmermann2

H. Zimmermann2

1 Knutz, P.C., Jennings, A.E., Childress, L.B., Bryant, R., Cargill, S.K., Coxall, H.K., Frank, T.D., Grant, G.R., Gray, R.E., Ives, L., Kumar, V., Le Houedec, S., Martens, J., Naim, F., Nelissen, M., Özen, V., Passchier, S., Pérez, L.F., Ren, J., Romans, B.W., Seki, O., Staudigel, P., Tauxe, L., Tibbett, E.J., Yokoyama, Y., Zhang, Y., and Zimmermann, H., 2025. Site U1603. In Knutz, P.C., Jennings, A.E., Childress, L.B., and the Expedition 400 Scientists, NW Greenland Glaciated Margin. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 400: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.400.103.2025

2 Expedition 400 Scientists’ affiliations.

1. Background and objectives

Site U1603 (proposed Site MB-23A) is located at 72°59.04′N, 62°58.83′W in Baffin Bay at 1801 meters below sea level (mbsl), below a protrusion of the northwest Greenland margin shaped by the Melville Bugt Trough Mouth Fan (TMF) (Figure F1). The site targets an expanded drift-channel succession situated on the lower slope between two paleo–ice sheet outlets that represent major drainage routes for the northern Greenland ice sheet (NGrIS) into Baffin Bay (Knutz et al., 2019; Newton et al., 2017, 2021). The drilling strategy was to core a continuous high-resolution record of ice-ocean processes spanning the early late Pleistocene.

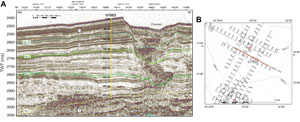

Selection of Site U1603 was guided by regional 2D and high-resolution seismic data from where 10 horizons were mapped (including the seabed), defining 11 seismic units of the prograded TMF system (Knutz et al., 2019) (Figure F2). The strategy was to obtain a continuous high-resolution record spanning the early late Pleistocene by coring through Seismic Horizons 8–11 into a stratified interval within Seismic Unit 8, which appears to predate the channel formation. Site U1603 is paired seismic-stratigraphically with Site U1604, located 16 nmi (~30 km) to the northwest.

The drift-channel succession cored at Site U1603 is influenced by the circulation of deepwater masses in Baffin Bay, which is poorly constrained by oceanographic data but may be influenced by a southward flow along the Greenland margin that counters the surface currents (Tang et al., 2004). Gyre pulses of the West Greenland Current may overflow the site at intermediate water depths (e.g., to 800 mbsl) (Münchow et al., 2015). The sediment sequence thickens nearer to the channel margins, most prominently on the northern flanks of the channels (Knutz et al., submitted). The succession is hypothesized to represent interactions between bottom contour currents and sediments supplied by the NGrIS through glacial–interglacial cycles. Increased glacigenic sediment fluxes may be expected during periods when ice was grounded on the outer shelf and during phases of ice sheet retreat. The first two scientific objectives for Sites U1603 and U1604 are (1) to test the hypothesis that the NGrIS underwent significant deglaciation at intervals within the frequency range of orbital eccentricity (~100–400 ky) (Schaefer et al., 2016; Knutz et al., 2019) potentially related to exceptionally warm or prolonged super-interglacials (Christ et al., 2023) and (2) to achieve a long-term understanding (e.g., the last 0.5 My or older) of marine-based ice sheet dynamics and phasing relations between ice streams draining different sectors of the North American and Greenland ice sheets. In particular, we hope that the records can provide insights to ocean conditions through glacial terminations and ice-ocean dynamics associated with the different stages of ice sheet configurations (Hiscott et al., 1989; Simon et al., 2014), which may have far-field effects such as those associated with the opening/closing of the Canadian Arctic straits (Jennings et al., 2022; Kelleher et al., 2022; Lofverstrom et al., 2022) (Figure F3). Finally, the multiproxy data collected at deepwater Sites U1603 and U1604 will contribute to the third scientific objective of testing the regolith hypothesis for the change in orbital insolation frequency across the mid-Pleistocene transition (Clark and Pollard, 1998).

Triple-hole coring was planned for Site U1603 using the advanced piston corer/half-length advanced piston corer (APC/HLAPC) systems, with a target depth of 250 m core depth below seafloor, Method A (CSF-A), in the first two holes and 422 m CSF-A in the third hole. Downhole logging with the triple combo, Versatile Seismic Imager (VSI), and Formation MicroScanner (FMS)-sonic tool strings was planned for the deepest hole.

2. Operations

2.1. Port call

Expedition 400 began in Reykjavík, Iceland, at Skarfabakki Harbour at 0815 h on 12 August 2023. The Expedition 395 science party departed the R/V JOIDES Resolution on 12 August, and on 13 August the crew, staff, and science party of Expedition 400 boarded the vessel, with the oncoming JOIDES Resolution Science Operator technical staff arriving at 0900 h and the science party at 1445 h. Immigration checks for those sailing were conducted dockside during the afternoon and completed by 1600 h. The science party began expedition preparation and received orientations including life at sea and safety training along with introductions to the laboratories during the rest of the port call. The two ice navigators were set up with internet access, and the ice analysis and reporting routine was initiated.

Freight was completed throughout the port call and included off-going shipments of core and refrigerated and frozen samples as well as the loading of sepiolite (drilling mud), drilling equipment, and fresh and frozen foods. On 16 August, fuel was bunkered and a boat drill was conducted.

The vessel was readied for departure, and the pilot came on board at 0745 h on 17 August. The tugboats were secured shortly after, and the last line was released at 0806 h, marking the official start of the initial transit. By 0822 h, the tugboats were released; the pilot departed, and our sea passage to Site U1603 began at 0824 h.

2.2. Site U1603

Hole location, water depth, and the number of cores recovered are listed in Table T1. All times are local ship time (UTC − 3 h) unless otherwise noted.

Site U1603 was the first site occupied during Expedition 400. JOIDES Resolution completed the 1721 nmi transit from Iceland to Site U1603 in 153.2 h (6.4 days) at an average speed of 11.3 kt (including pilotage). A favorable current and wind contributed greatly to this average speed as we transited up the west side of Greenland. The vessel arrived on site at 1355 h on 23 August 2023, and the thrusters were lowered and the dynamic positioning (DP) system was engaged. At 1420 h, operations began for Site U1603.

2.2.1. Hole U1603A

The first attempt to spud Hole U1603A was an APC shot from 1802.0 meters below rig floor (mbrf), which resulted in a water core. The pipe was lowered 5 m and shot from 1807 mbrf. Hole U1603A was spudded at 0425 h on 24 August 2023 with 4.65 m recovered. The seafloor was calculated at 1800.8 mbsl (1811.9 mbrf; meters below rig floor is 11.1 m greater than meters below sea level).

APC coring continued through Core 400-U1603A-13H at 118.6 m CSF-A. The advanced piston corer temperature (APCT-3) tool was run on Cores 4H, 7H, 10H, and 13H. The core liner shattered on Core 13H and had to be pumped out of the liner.

At 1515 h on 24 August, the bridge notified the drill floor that an iceberg had entered the Red Zone (i.e., would be within 3 nmi of the vessel in less than twice the time it will take to trip up to 50 m CSF-A). The drill string was tripped up with the top drive from 109.1 to 43.21 m CSF-A at 1600 h. From 1600 to 1715 h, the vessel tracked two icebergs. At 1715 h, with one of the icebergs entering the Termination Zone (within 1 nmi of the vessel), the order was given to pull the pipe clear of the seafloor. The drill string was again pulled up with the top drive, this time to 1778.3 mbrf, clearing the seafloor at 1742 h and ending Hole U1603A. The vessel was moved 500 m south in DP mode. The closest iceberg passed within ~0.6 nmi of the vessel. Once it was safe to do so, the vessel was moved back over location and offset 10 m northwest of Hole U1603A, coming into position at 2000 h on 24 August.

A total of 13 cores were taken in Hole U1603A over a 118.6 m interval with 100.3% recovery. Temperature measurements using the APCT-3 tool were taken on Cores 4H, 7H, 10H, and 13H. Total time on Hole U1603A was 27.6 h (1.15 days). In total, 1.25 h were spent waiting on ice, and an additional 1.25 h of operational time was spent pulling out of Hole U1603A to prepare to wait on ice.

2.2.2. Hole U1603B

Hole U1603B was spudded at 2035 h on 24 August 2023. It was washed down to 109.1 m CSF-A by 0100 h on 25 August. Coring began with Core 2H from 109.1 m CSF-A and continued through Core 5H at 147.1 m CSF-A. After an overpull and drillover of Core 5H, we switched to the half-length APC (HLAPC) system. HLAPC coring started with Core 6F and continued through Core 27F, shot from 243.9 m CSF-A at 0230 h on 26 August. The barrel pulled free from the formation with no overpull; however, the coring line could not pull the barrel up. The drill string was tripped back up to the vessel with the bit clearing the rig floor at 1157 h, ending Hole U1603B. Once the bottom hole assembly (BHA) was on board, the core barrel was recovered with 0.08 m of material, likely from the push down trying to free the barrel. The final depth for Hole U1603B was 244.0 m CSF-A. The vessel was offset 10 m northwest of Hole U1603B.

A total of 26 cores were taken in Hole U1603B over a 134.9 m interval with 91.0% recovery. Total depth for Hole U1603B was 243.98 m CSF-A, and total time was 42.24 h (1.76 days). In total, 2.25 h were spent waiting on ice and an additional 5.75 h of operational time were spent starting a new hole and drilling down in Hole U1603B to the depth of penetration in Hole U1603A.

2.2.3. Hole U1603C

Hole U1603C was spudded at 0105 h on 27 August 2023, and the hole was drilled down over the next 7.75 h. Cores 2R–9R advanced from 211.5 to 285.0 m CSF-A and recovered 22.78 m (31%). At 1945 h, ice moved within 3 nmi of the vessel, and we raised the drill string to 22.3 m CSF-A and began waiting on ice.

At 0000 h on 28 August, ice entered the 1 nmi exclusion zone. We raised the drill string, clearing the seafloor at 0009 h and ending Hole U1603C, and continued waiting on ice. The vessel was moved 1200 m east-northeast and then 700 m east-southeast in DP mode to maintain a safe distance from the ice. By 0330 h, the ice had cleared the site and the vessel was positioned 10 m northwest of Hole U1603C.

A total of eight cores were taken in Hole U1603C over a 73.5 m interval with 31% recovery. Total depth for Hole U1603C was 285.0 m CSF-A, and total time was 36.24 h (1.51 days). In total, 2.25 h were spent waiting on ice and an additional 2.0 h of operational time were spent pulling out of Hole U1603C to wait on ice.

2.2.4. Hole U1603D

Hole U1603D was spudded at 0455 h on 28 August 2023 and, with a wash barrel, was drilled ahead to 102.0 m CSF-A. As ice once again neared the site, we decided to install a free fall funnel (FFF) to allow us to reenter Hole U1603D. The FFF was deployed at 0950 h, and by 1030 h we resumed drilling ahead in Hole U1603D to 189.0 m CSF-A. At 1400 h, ice moved within 3 nmi of the vessel, and we raised the drill string to 22.3 m CSF-A by 1515 h and began waiting on ice for the remainder of the day.

By 0015 h on 29 August, the ice had cleared the site. The drill string was lowered to 169.6 m CSF-A, and we washed back to 189.0 m CSF-A before drilling ahead to 269.4 m CSF-A. Cores 400-U1603D-2R through 8R advanced from 269.4 to 333.2 m CSF-A and recovered 14.62 m (24%). At 1400 h, ice moved within 3 nmi of the vessel, and we raised the drill string to 22.3 m CSF-A by 1545 h and began waiting on ice. Ice then entered the 1 nmi exclusion zone, and we raised the drill string, clearing the seafloor at 1930 h. The vessel was moved 1000 m north in DP mode to maintain a safe distance from the ice. By 2157 h, we began to move back toward the site, and the vessel was in position over Hole U1603D by 2348 h on 29 August.

At 0100 h on 30 August, we began preparing the subsea camera system to assist with reentering Hole U1603D. At 0320 h, we successfully reentered the hole and recovered the subsea camera system. The drill string was lowered to 294.4 m CSF-A, and we washed back to 318.5 m CSF-A before encountering material that had fallen into the bottom of the hole. A center bit was dropped, and we washed to 333.2 m CSF-A by 0800 h. Cores 9R–18R advanced from 333.2 to 422.0 m CSF-A and recovered 28.69 m (32%). Sepiolite (drilling mud) was swept in the hole, and the bit was released at 2315 h to prepare for logging Hole U1603D. We then tripped the drill string up to 50.8 m CSF-A in preparation for logging.

The modified triple combo (quad combo) tool string was rigged up and, following a repair to the logging winch, was deployed to the base of Hole U1603D (419.5 m CSF-A). The quad combo measures natural gamma ray, density, acoustic velocity, resistivity, magnetic susceptibility (MS), and density. Following a complete pass of the hole, the quad combo was pulled to the rig floor and broken down. The VSI was rigged up, and the protected species watch began at 1600 h on 31 August. The VSI was deployed but almost immediately experienced a communication issue. The tool was brought back on board and repaired. At 1800 h, the VSI was deployed to 413.1 m CSF-A, and stations were measured uphole until 2120 h, when fog impacted visibility and the ability to monitor for protected species. After the VSI was brought back on board and broken down, the FMS-sonic tool string was assembled and deployed. The FMS-sonic tool string was run, and the tools were back on deck by 0345 h on 1 September. With logging completed, we tripped the pipe out of the hole, clearing the rig floor at 0900 h and ending Hole U1603D.

A total of 17 cores were taken in Hole U1603D over a 152.6 m interval with 28.4% recovery. Total depth for Hole U1603D was 422 m CSF-A, and total time was 104.64 h (4.36 days). In total, 21.5 h were spent waiting on ice, and an additional 24.75 h of operational time were spent drilling down in Hole U1603D to the depth of penetration in Hole U1603C and later pulling out of and reentering Hole U1603D.

2.2.5. Hole U1603E

An APC/extended core barrel (XCB) BHA was made up, and we began tripping the drill pipe back to the seafloor at 1200 h on 1 September 2023. The vessel was offset 10 m northwest in DP mode, and the pipe was pumped with a cleanout tool while the tracer pumps were running. Hole U1603E was spudded at 1745 h, and Core 1H recovered 6.94 m. Core 2H advanced to 16.4 m and recovered 9.75 m (103%). Cores 3H–6H each advanced 9.5 m but recovered almost no material (less than 20 cm each). The deplugger was run in the pipe. Core 7F advanced from 54.4 to 59.1 m CSF-A and recovered 0.31 m (7%). Following Core 7F, we decided to abandon Hole U1603E due to lack of recovery, and the drill string was tripped out, clearing the seafloor at 0140 h on 2 September.

A total of seven cores were taken in Hole U1603E over a 59.1 m interval with 29.6% recovery. Total time for Hole U1603E was 16.8 h (0.7 days).

2.2.6. Hole U1603F

The vessel was offset 10 m southeast of Hole U1603A to hopefully improve recovery and allow for better correlation with other holes. Hole U1603F was spudded at 0235 h on 2 September 2023. Cores 1H–5H advanced from 0 to 44.0 m CSF-A and recovered 45.49 m (103%). Core 6F (44.0–48.80 m CSF-A; 4.73 m recovered) was cored with the HLAPC system to help adjust core spacing to cover gaps in Hole U1603A. Cores 7H–15H advanced from 48.8 to 134.3 m CSF-A and recovered 66.71 m (78%). The APCT-3 tool was run on Cores 4H and 10H. We then began pulling the drill string out of the hole, clearing the seafloor at 1935 h. The drill string was tripped up with the bit at the surface at 0030 h on 3 September. The drill floor was secured for transit, and the thrusters were raised and secured for transit at 0145 h, ending Hole U1603F and Site U1603.

A total of 15 cores were taken in Hole U1603F over a 134.3 m interval with 87.1% recovery. Total time for Hole U1603F was 24 h (1.0 days).

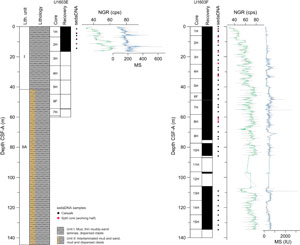

3. Lithostratigraphy

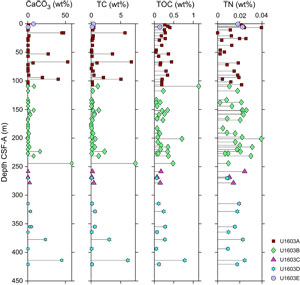

Site U1603 consists of six overlapping holes (U1603A–U1603F) cored to a total depth of 422 m CSF-A, with Holes U1603A–U1603D each recovering ~120 m thickness at successive depths and Holes U1603E and U1603F targeting the uppermost 130 m to replicate stratigraphy recovered in Hole U1603A. Of the 422 m thick section, 243.6 m of sediments were recovered. Based on those recovered sediments, the stratigraphy at this site is divided into four lithostratigraphic units (Figure F4; Table T2). named lithofacies are sedimentary; are present in all four units with variable predominance; and include mud, calcareous mud, interlaminated to interbedded mud and sand, diamicton, and sandy mud with common clasts (Figure F4).

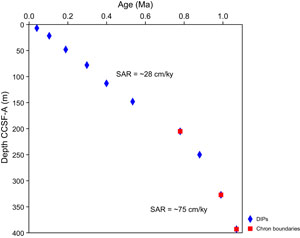

Sediments recovered are consistent with the site location at the base of the continental slope proximal to a glaciated progradational margin deposited during the Early to Late Pleistocene. The deposits in the uppermost ~243 m of the succession (Lithostratigraphic Units I and II) are consistent with downslope and along-slope sedimentation on a channel levee system with high sedimentation rates (~28 cm/ky on average) (see Age model). The uppermost ~42 m (Unit I) consists of mud with irregular sand laminae and dispersed clasts. A thick sequence of interlaminated to interbedded mud and sand is predominant between ~42 and 243 m CSF-A (Unit II) and is divided into two subunits distinguished by laminae/bed thickness, proportion of mud versus sand, and clast occurrence. Subunit IIA consists of finer laminae, thinner sand beds, and a lower proportion of sand, whereas Subunit IIB (~145–243 m CSF-A) has thicker laminae and beds, a higher proportion of sand, and a relatively higher clast abundance. The deposits below 243 m CSF-A show a higher average sedimentation rate (~75 cm/ky) (see Age model). From 243 to 374 m CSF-A (Unit III), weakly stratified mud lithologies are dominant, sand lithofacies are rare, and clast occurrence increases significantly. In the lowermost ~46 m of Hole U1603D (Unit IV), weakly stratified muds similar in character to Unit III are present, but this unit also contains an interval of calcareous mud and various types of soft-sediment deformation that are absent in Unit III.

3.1. Unit descriptions

Site U1603 is divided into four lithostratigraphic units (I–IV; youngest to oldest), with Unit II divided into two subunits (IIA and IIB) (Figure F4). Significant downhole changes in lithology were determined using a combination of visual core description, microscopic characterization (using smear slides, grain mounts, and thin sections), reflectance spectroscopy and colorimetry, and bulk and clay mineralogical analyses using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (see Lithostratigraphy in the Expedition 400 methods chapter [Knutz et al., 2025]).

3.1.1. Unit I

- Intervals: 400-U1603A-1H-1, 0 cm, to 5H-6, 112 cm; 400-U1603E-1H-1, 0 cm, to 5H-CC, 17 cm*; and 400-U1603F-1H-1, 0 cm, to 5H-5, 122 cm (asterisk denotes recovered extent in that hole [due to drill down or lack of recovery below]; see Table T2)

- Depth: 0–41.7 m CSF-A

- Thickness: 41.7 m

- Age: Pleistocene–Holocene?

- Lithology: mud, thin muddy-sand laminae, dispersed clasts

Lithostratigraphic Unit I consists of grayish brown (uppermost two cores) and greenish to bluish gray mud (Core 400-U1603A-3H through Section 5H-6, 112 cm). Beds of thinly (millimeter scale) laminated mud alternate with massive mud layers on a ~1 m or thinner scale. Massive muds are sparsely and rarely moderately bioturbated. Clasts occur dispersed throughout the unit. Centimeter- to decimeter-scale interbeds of common to abundant clasts are also observed. Diagenetic color alteration (color banding) and iron-sulfide mineralization result in black mottling as both millimeter-scale patches and in discrete millimeter-scale laminae.

3.1.2. Unit II

3.1.2.1. Subunit IIA

- Intervals: 400-U1603A-5H-6, 112 cm, to 13H-CC, 56 cm*; 400-U1603B-2H-1, 0 cm*, to 5H-5, 118 cm; 400-U1603E-5H-CC, 17 cm*, to 7H-CC, 12 cm*; and 400-U1603F-5H-5, 122 cm, to 15H-CC, 23 cm* (asterisk denotes recovered extent in that hole [due to drill down or lack of recovery below]; see Table T2)

- Depth: 41.7–144.84 m CSF-A

- Thickness: 103.14 m

- Age: Pleistocene

- Lithology: interlaminated mud and sand, mud with dispersed clasts

Lithostratigraphic Subunit IIA consists primarily of dark gray, millimeter-scale interlaminated mud and sand alternating with greenish gray to grayish brown mud, typically in continuous intervals on the order of 2–3 m. Sand beds 1–3 cm thick are overall rare but are common in specific intervals. Dispersed (<5%) to common (5%–10%) clasts occur in the mud lithofacies as coarse sand to fine gravel. Clasts containing pink feldspathic grains are common. Plutonic pebble-sized clasts are rare and not associated with a particular lithofacies. Clast abundance is generally higher in Subunit IIA than in Unit I. Bioturbation is rare in this subunit.

3.1.2.2. Subunit IIB

- Intervals: 400-U1603B-5H-5, 118 cm, to 26F-3, 55 cm, and 400-U1603C-2R-1, 0 cm*, to 5R-CC, 28 cm* (asterisk denotes recovered extent in that hole [due to drill down or lack of recovery below]; see Table T2)

- Depth: 144.84–242.59 m CSF-A

- Thickness: 97.75 m

- Age: Pleistocene

- Lithology: interlaminated to interbedded mud and sand, mud with sand and dispersed clasts

Lithostratigraphic Subunit IIB consists of dark gray thinly to thickly interlaminated to thinly interbedded mud and sand. Mud and sand laminae are 1–10 mm thick, and normally graded sand beds as thick as 4 cm occur throughout this subunit. Grayish brown mud intervals are a minor component of this unit. These intervals frequently have dispersed clasts and typically contain very sparse and irregularly occurring sand laminae and thin beds. In Subunit IIB, sand beds (>1 cm) are both more numerous and generally thicker and dispersed clasts occur more frequently than in Subunit IIA. Sand composition in this unit becomes more quartz rich. Bioturbation is rare, with a thin interval of common–abundant bioturbation in Sections 400-U1603B-22F-1 and 22F-2.

3.1.3. Unit III

- Intervals: 400-U1603B-26F-3, 55 cm, to 27F-CC, 8 cm*; 400-U1603C-6R-CC, 0 cm*, to 9R-CC, 14 cm*; and 400-U1603D-2R-1, 0 cm*, to 13R-3, 0 cm* (asterisk denotes recovered extent in that hole [due to drill down or lack of recovery below]; see Table T2)

- Depth: 242.59–374.83 m CSF-A

- Thickness: 132.24 m

- Age: Early Pleistocene

- Lithology: sandy mud to diamicton and thinly laminated mud

Lithostratigraphic Unit III consists of dark grayish brown thinly laminated mud with rare to common sand laminae, weakly stratified sandy mud, mud with dispersed clasts, and clast-poor diamicton. The interlaminated mud and sand lithofacies is expressed with very thin parallel laminae (~1 mm). The sandy mud contains very faint parallel bedding structures, which are difficult to see in visible light but are more distinguishable in X-ray images. Dispersed clasts occur solely in mud lithologies and occur in intervals ~20 cm thick. Unit III is distinguished from Unit II by the higher proportion of diamicton and mud with common clasts. Bioturbation is absent or unobservable due to drilling disturbance.

3.1.4. Unit IV

- Interval: 400-U1603D-13R-3, 0 cm, to 18R-CC, 8 cm

- Depth: 374.83–421 m CSF-A

- Thickness: 46.17 m

- Age: Early Pleistocene

- Lithology: mud and diamicton

Lithostratigraphic Unit IV consists of weakly stratified sandy mud and clast-poor muddy diamicton with intervals of thinly laminated mud. One bed of foraminifera-bearing calcareous clay was also observed. The mud intervals contain sedimentary structures including ripple cross lamination. Carbonate mud intraclasts (millimeter-scale diameter) occur as part of the clast fraction, which is otherwise dominated by plutonic and metamorphic lithologies. Bioturbation is rare, with the exception of one interval in Core 400-U1603D-13R. Synsedimentary microfaults, soft-sediment folds, and shear structures are common throughout most of this unit.

3.2. Lithofacies descriptions

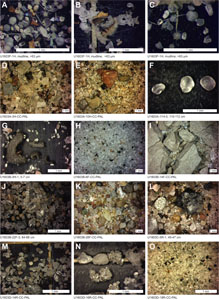

At Site U1603, four main lithofacies are identified based on lithology, sedimentary structures, and textural and other common characteristics. This set of lithofacies is interpreted to represent a range of ice-distal to ice-proximal glaciomarine sedimentary processes in a continental slope to base-of-slope environment (water depth = 1800 m). Lithofacies are described below, emphasizing visual description characteristics and supplemented with physical properties when relevant. Figure F5 highlights multiple lithofacies and their associated characteristics.

3.2.1. Lithofacies 1: mud

Lithofacies 1 consists of clay- and silt-sized terrigenous material and includes a large range in color spanning grayish yellow, grayish brown, and gray, including light to dark greenish gray and bluish gray. Sedimentary structures include massive/structureless, parallel laminations, and color banding (Figure F6). Individual mud laminae are <0.3–1 cm thick. Laminated mud intervals are typically <1 m thick and are often gradationally interstratified with mud that is massive and shows no clear evidence of lamination. Sand laminae (<1 cm) and very thin beds (1–3 cm) are present in some intervals, especially in gradational contact with Lithofacies 3 (interlaminated to interbedded mud and sand). Clasts are present in some intervals, ranging from sand-sized grains (0.063–2 mm) to sand blebs and pebble-sized clasts up to 6 cm in diameter. Where clasts occur, their abundance ranges from dispersed to common. Bioturbation is absent to sparse. There are very rare intervals with moderate bioturbation (e.g., interval 400-U1603A-13H-2, 0–80 cm). Mottling is present in rare intervals. Smear slides indicate that this mud lithofacies is composed of a mixture of clay and silt. The silt particles are commonly dominated by quartz and feldspar with common muscovite, amphibole, and rare accessory minerals.

Lithofacies 1 represents a continuum of slope depositional processes from suspension settling (hemipelagic) to bottom currents and low-concentration density flows. The sparse isolated clasts were likely delivered from ice rafting.

3.2.2. Lithofacies 2: calcareous mud

Lithofacies 2 consists of yellow-brown calcareous mud, which occurs in 1–30 cm thick beds. Smear slide analyses show that this lithofacies is dominated by mud-sized particles of abiotic carbonate, including rhombs, with minor siliciclastic components (Figure F7A). Bulk XRD analyses of selected intervals confirm that the carbonate mineralogy is dolomite and high-magnesium calcite. Carbonate contents, which range 19.4–58.4 wt% (n = 8), are significantly higher than those of enclosing sediments (average = 1.6 wt%; median = 0.4 wt%; n = 54) (see Geochemistry). Lithofacies 2 is also characterized by low MS values (approaching 0), an increase in L*, and an increase in the difference between red and blue color magnitudes relative to other lithofacies. The expression of Lithofacies 2 varies throughout the succession (Figure F7C–F7F). Some occurrences are isolated laminae or thin beds enclosed by gray siliciclastic-dominated deposits. Upper and lower contacts may be sharp or gradational. More complex occurrences are characterized by isolated blebs, laminae, or thin beds that grade upward into a thicker bed of calcareous mud before transitioning upward to isolated laminae within gray enclosing lithofacies. At Site U1603, there does not appear to be a systematic association between Lithofacies 2 and any other lithofacies.

Although Lithofacies 2 occurs throughout the succession, it is relatively rare in this otherwise siliciclastic-dominated succession and thus may indicate transient shifts in source regions for ice-related transport. The depositional processes involved in emplacing these layers (e.g., by ice rafting) does not appear to deviate strongly from adjacent, noncalcareous lithofacies (Lithofacies 1, 3, and 4). Localized occurrences of granule- to fine pebble–sized clasts of dolomitized fossiliferous limestone and dolostone (massive and nonfossiliferous) within the succession may provide some indication of provenance and glacial source regions for Lithofacies 2 (Figure F7B).

3.2.3. Lithofacies 3: interlaminated to interbedded mud and sand

Lithofacies 3 consists of interlaminated to interbedded mud and sand with variable proportions of mud versus sand throughout the succession. The mud component is dark gray to dark brown in color and commonly laminated (Figure F8). Bioturbation in the mud component varies but is typically sparse. The composition of the mud component based on smear slide analysis reveals varying mixtures of clay and silt, with the silt particles dominated by quartz and feldspar, with muscovite, amphibole, and other accessory minerals. The sand component of this lithofacies occurs within laminations (<1 cm) as well as very thinly bedded (1–3 cm) and rare thinly bedded (3–10 cm) layers. Sand grain size varies from very fine in the thinnest laminations to up to medium sand in the >2 cm thick beds. Normal grading is observed in >0.5 cm thick beds. Some of the sand beds displaying thicknesses ≥1 cm have internal structures including parallel lamination, ripple cross lamination, and centimeter-scale scour surfaces (Figure F8). Bioturbation in the sand component is variable but is typically absent to sparse. The sand composition based on smear slide analysis is dominated by angular quartz and feldspar grains, with lesser amounts of amphibole, mica (muscovite and biotite), and igneous rock fragments. Grains are typically angular and show little to no evidence of alteration. In general, this lithofacies does not contain abundant dispersed clasts, but there are some intervals where isolated grains and granule to small-pebble clasts are observed (Figure F8).

Lithofacies 3 represents a complex mixture of depositional processes on the continental slope, including downslope (turbidity current) processes, contour-current deposition, and suspension settling from plumes. The thicker, coarser grained, and normally graded sand beds are likely derived from turbidity currents, whereas the specific depositional process of the mud component is similar to Lithofacies 1. The sparse isolated clasts were likely delivered by ice rafting.

3.2.4. Lithofacies 4: diamicton and sandy mud with common clasts

Lithofacies 4 consists of poorly sorted sediments with a matrix of sand and mud and a clast abundance of more than 1%, including diamicton and sandy mud with common clasts (Figure F9). These lithofacies rarely exceed more than 1 m in thickness, and both upper and lower bed boundaries are typically gradational. Collectively, the clasts comprise mainly polymict assemblages of igneous and metamorphic lithologies and occur both as isolated outsized clasts and as clast clusters. Clast sizes range from sand sized up to pebbles ~6 cm in diameter. Stratification of the diamict matrix on a decimeter scale is common and is evident from X-ray images. Locally, the matrix is organized into horizontal planar millimeter- to centimeter-scale poorly sorted laminae of sand and granules. The sandy mud is characterized by sand-rich (>25%) muds with thin (<3 mm) to thick (3–10 mm) parallel laminations that are generally less visually distinctive than the interlaminated lithofacies. A high degree of bioturbation may obscure the laminations or present a mixed-sediment component suggestive of postdepositional disturbance.

Lithofacies 4 represents sedimentation in a lower continental slope environment with a strong glacigenic influence. Sandy mud and muddy diamicton with clast clusters can be interpreted as hemipelagic sediment with ice-rafted debris (IRD), whereas some of the stratified clast-poor sandy diamicton and sandy mud could have originated as gravity flows.

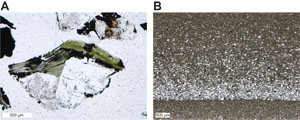

3.3. Diagenesis

Diagenetic features at Site U1603 include iron sulfide minerals and carbonate concretions. The iron sulfide minerals are typically associated with sand laminae or blebs, forming prominent black laminae or patches in cores. They are often highlighted on X-ray images by dense material. Thin section analysis shows that the iron sulfides form fine coatings on grains, with biotite grains being most affected (Figure F10A). A few calcite-cemented concretions were observed in Sections 400-U1603A-10H-2, 400-U1603B-22F-3, and 400-U1603C-8R-2. In these concretions, intergranular cementation aided in the preservation of primary sedimentary structures such as graded fine sand and silt laminae (Figure F10B).

In Holes U1603A, U1603C, and U1603D, intervals of featureless or slightly laminated mud are often associated with color banding, alternating reddish and greenish layers, which may be associated with change in the iron oxidation state in sediments (see Geochemistry).

3.4. Smear slide and thin section analysis

A series of smear slides were taken during core description to ascertain the characteristics and composition of mud and very fine sand. Clay was too fine grained for mineralogical identification using petrographic methods. With the exception of samples discussed below, silt- and sand-sized grains are of terrigenous origin, dominated by quartz and feldspar minerals, with lesser amounts of mica, amphibole, and other accessory grains. Grains are typically angular to subangular, and minerals such as feldspar show no signs of alteration. Smear slides of calcareous mud intervals were also prepared and show that they are dominated by clay- to silt-sized fragments and rhombs of calcite and dolomite. Quartz, feldspar, and clay are present in minor amounts.

To determine the composition of prominent black laminae and blebs in mudstone and interlaminated mudstone–sandstone facies, a grain mount was made of black-coated, unconsolidated sand grains enclosed in a bleb (Sample 400-U1603A-8H-2W, 1–4 cm; TS01). Petrographic examination under transmitted and reflected light shows the black material to be opaque with an amorphous or cubic to stellate habit and pale yellow reflectance, consistent with iron sulfide minerals such as pyrite. Mica (possibly biotite) grains are most affected by pyritization, with quartz, feldspar, and accessory minerals being less affected. Of note, many of the feldspar grains in this sample were undergoing alteration (e.g., sericitization).

To preliminarily assess the composition of IRD, grain mounts were made from pebbles that were prominent in the biostratigraphy core catcher sample (400-U1603B-26F-CC, 23–28 cm; TS02 and TS04). This interval is composed of Lithofacies 2 (calcareous mud). The pebbles, typically subrounded, are dominated by fragments of variably dolomitized limestone and dolostone. Fragments of plutonic igneous rocks, chert, sandstone, and siltstone occur in relatively minor amounts. Some carbonate clasts contain altered fossils, including a coral (likely Paleozoic), brachiopod shell fragments, and a probable trilobite fragment, along with peloids and recrystallized shell debris. One clast contains silicified ooids. Dolomitization style is variable, ranging from finely crystalline to coarsely crystalline to saddle (hydrothermal) dolomite. In one sandstone clast, framework grains are rimmed by hematite.

3.5. Clay and bulk mineralogy results

XRD analyses were performed on 11 powdered bulk samples from Holes U1603A–U1603C, with sample selection based on major lithologic changes. In addition, 11 samples were taken from Holes U1603C–U1603E to determine the clay mineral compositions in Lithostratigraphic Units I, III, and IV and Subunit IIB. A qualitative and ratio-based summary of XRD results is given in Tables T3 and T4 for bulk and clay compositions, respectively.

The analyses of bulk samples in Hole U1603A were performed on three of the main identified lithofacies: mud, calcareous mud, and diamicton and sandy mud with common clasts. A supplementary bulk analysis was performed on a concretion found in Section 10H-2. The mud facies in Unit I sampled in Section 5H-4 is dominated by quartz with common feldspars and plagioclase. In addition, clay XRD analyses performed on material from Hole U1603E from Lithofacies 1 in Unit I show dominant illitic composition. Bulk analyses of the calcareous mud facies (Lithofacies 2) sampled in Sections 400-U1603A-5H-6 and 11H-5 indicate that quartz is still abundant, but calcite and dolomite are also identified as common phases. The concretion in Section 10H-2 contains traces of dolomite, likely occurring as intergranular cement.

Analyses of bulk samples in Hole U1603B specifically targeted calcareous mud (Lithofacies 2) and diamicton (Lithofacies 4). Based on samples of Lithofacies 2 from Sections 26F-3 and 26F-CC, dolomite and calcite are abundant phases in the calcareous mud, along with quartz. For Lithofacies 4, the sample from Section 2H-6 contains magnesium calcite in abundance, whereas the sample from Section 26F-4 is dominated by dolomite.

In Hole U1603C, samples for bulk XRD analysis were collected from Sections 3R-2 and 5R-2 (base of Subunit IIB) and Section 9R-2 (top of Unit III). All samples present a similar composition of abundant quartz and common feldspars (including plagioclase) in Lithofacies 1 and 3. XRD analyses for clay minerals were performed for Lithofacies 1 (mud) from Sections 2R-2 and 5R-2 in Subunit IIB and from Section 7R-2 in Unit III. All samples show a dominantly illitic composition with chlorite as a secondary component. A similar composition characterizes Lithofacies 3 (interlaminated to interbedded mud and sand) and Lithofacies 4 (sandy mud with common clasts) in Unit III, based on analysis of samples from Sections 8R-2 and 9R-2. Smectite is a trace component in samples from Sections 5R-2, 7R-2, and 9R-2.

For Hole U1603D, clay XRD analyses were performed to investigate the clay mineralogy of Lithofacies 1 within Unit III. All samples are characterized by a primarily illitic composition. Smectite is present in greater abundance downhole (e.g., Section 8R-5). Kaolinite is a common mineral in two samples (Sections 2R-2 and 8R-5).

3.6. Preliminary depositional interpretation

Site U1603 recovered a sequence of Holocene to Early Pleistocene sediments from the continental slope and base of slope offshore the northwest Greenland margin. Unit I and Subunits IIA and IIB reveal a complex mixture of depositional processes on the continental slope that include suspension settling from plumes, turbidity current and contour current processes, and ice rafting. Interbedded diamicton and stratified sandy mud (Units III and IV) indicate the glacigenic origin of the sediments and may record ice sheet processes that occurred on the shelf. Several calcareous mud intervals in an otherwise siliciclastic-dominated succession may suggest episodes of variable sediment provenance in the depositional system. A short sequence containing foraminifera-bearing mud (Unit IV) suggests a prolonged interval of relatively enhanced productivity in open-marine conditions during the Early Pleistocene.

4. Biostratigraphy

4.1. Biostratigraphy and paleoenvironment

Core catcher samples from Holes U1603A–U1603D, together with additional samples from within cores, were examined for foraminifera, diatoms, dinoflagellate cysts (dinocysts), and other palynomorphs. The additional samples were taken from cores where variations in lithology were observed as an attempt to identify microfossil-rich horizons. Sampling targets included intervals of massive muds, increased bioturbation, and muds with dispersed clasts that coincided with low natural gamma radiation (NGR) values, as well as grayish brown and medium greenish gray carbonate-rich intervals. Mudline samples from Holes U1603A and U1603F were also examined. Cores from Holes U1603E and U1603F, which provide a second copy of the uppermost ~130 m of the cored section, were not examined. Observations of foraminifera from palynomorph and diatom slide preparations were integrated in the overall foraminifera evaluations.

The muds and interlaminated sands and muds typical of Site U1603 are generally barren of in situ microfossils besides a few intervals where some groups become abundant (Figure F11). Where foraminifera appear, they remain as rare occurrences, except in two distinct intervals in Cores 400-U1603B-22F and 400-U1603D-13R where they are common. Diatoms were found in about 6% of all samples examined, with trace to rare amounts of specimens and species. Palynomorph preparations revealed persistent contributions of phytoclasts and reworked terrestrial pollen and spores. The observed microfossil specimens and assemblages for all groups are typical of cold-water polar environments, and in situ dinoflagellate species are typical of coastal or neritic environments. Observed specimens and assemblages are broadly consistent with a Pleistocene age. The species have long stratigraphic ranges and provide limited age control.

4.1.1. Foraminifera

Two mudline samples were examined for Holes U1603A and U1603F. Both contain abundant oxidized metallic grains and fine quartz sand (Figure F12). Sample 400-U1603A-1H-1, 0 cm, which yielded an extremely small sand sample, contains a few large diatoms but no foraminifera. Also of note are two tektites and several clasts of green and brown glass with indications of a bubble texture (Figure F12A). Mudline Sample 400-U1603F-1H-1, 0 cm, contains diverse biogenic grains, including radiolarians, abundant large (100–200 µm) centric diatoms, setae of the diatom Chaetoceros spp., and rare agglutinated benthic foraminifera including Hormosinelloides guttifera and Textularia earlandi (Figure F13A–F13C).

All lithologies that characterize Site U1603 were challenging to disaggregate, especially in the uppermost 5–10 cores of Hole U1603A where muds dominate (Figure F11). Because of the high clay content in much of the recovered sediment, the sieved >63 µm residues are often small, becoming significantly larger in sand-rich and diamicton intervals. Figure F13D–F13M illustrates the range in variability of >63 µm residues, emphasizing the dominance of lithics, mineral grains, and other biological materials. Quartz typically dominates the sands, which is well sorted in some intervals (Figure F13H, F13O), together with transported lithic clasts of a variety of lithologies, including typically gray carbonates in variable quantities (Figure F13E, F13I). Other notable grains are extremely rounded quartz grains that are common in many samples, as well as grains of pyrite-cemented clusters of quartz sand (Figure F13N).

Of the processed foraminifera samples, 41 of the 49 core catcher samples from Site U1603 are devoid of foraminifera and 8 have rare to common foraminifera. Of the 54 additional samples taken from targeted intervals, 32 are also devoid of foraminifera. Rare to common calcareous foraminifera appear in 22 residues. The >125 and 63–125 µm sieved fractions were examined separately; however, because of the typically low numbers of foraminifera, observations are combined. Planktonic and benthic foraminifera are also presented together here.

The core catchers and additional samples in which rare foraminifera (planktonic and benthic) are observed are shown in Table T5. A single species of planktonic foraminifera was recorded: the polar specialist Neogloboquadrina pachyderma. This is most often seen as only a couple of specimens per sample (Figure F13M) but with some notable exceptions (Figure F13J) in Samples 400-U1603A-8H-6, 25–27 cm; 400-U1603B-22F-3, 64–66 cm, and 22F-4, 45–47 cm; and 400-U1603D-13R-4, 119–121 cm, and 13R-CC where N. pachyderma is more abundant (Figure F13J, F13M). A variety of N. pachyderma morphotypes are observed that match the five-morphotype classification of Eynaud et al. (2009) and El Bani Altuna et al. (2018). Noteworthy in Section 400-U1603A-8H-6 and Core 400-U1603D-13R is the common occurrence of a large five-chambered morphotype with an open umbilicus. This could be Nps-4 of El Bani Altuna et al. (2018), but it is also comparable to Neogloboquadrina dutertrei (although lacking an umbilical tooth) and Neogloboquadrina atlantica. This sample also contains teratoid N. pachyderma specimens, which display irregular coiling and/or aperture placement. These are reminiscent of Neogloboquadrina polusi (Androsova, 1962), which was also reported by Aksu (1985) in the central Arctic Ocean. N. polusi is currently synonymized under N. pachyderma (Brummer and Kučera, 2022). Preliminary N. pachyderma coiling counts in Samples 400-U1603D-13R-CC and 13R-4, 119–121 cm (calculated as ~5% dextral) suggest that the planktonic assemblages are monospecific and do not contain the warmer water species Neogloboquadrina incompta. It is noted that the sand fraction of the bottom core catcher sample (13R-CC; 420.92 m CSF-A) is composed almost entirely of an extremely well sorted, foraminifera-barren fine sand falling in the 63–125 µm sieved fraction. This particle sorting is suggestive of current winnowing and a contourite facies (Figure F12).

Similarly, much of the cored sequence at Site U1603 lacks benthic foraminifera, especially the interlaminated sands and muds. Even in the most foraminifera-bearing samples, only single to a few benthic foraminifera specimens are observed, with the exception of Samples 400-U1603D-13R-4, 119–121 cm, and 13R-CC and 400-U1603B-27F-CC, where specimens are sufficiently abundant (>100 specimens) to be considered an assemblage (Table T5). In Sample 400-U1603D-13R-4, 119–121 cm, the ecologically flexible Cassidulina reniforme is most common, together with common Stetsonia horvathi and rare Cassidulina neoteretis/teretis, the latter being typical of chilled Atlantic waters (Jennings and Helgadottir, 1994; Cage et al., 2021). Sample 400-U1603B-27F-CC contains dominant Elphidium clavatum, a few examples of the agglutinated benthic species Recurvoides spp., and rare Islandiella inflata. E. clavatum is typical of Arctic glaciomarine environments in shelf and slope settings without perennial sea ice cover but with seasonal ice (Hald and Korsun, 1997; Jennings et al., 2020). Other species observed at Site U1603 include the Arctic species Buliminella elegantissima, Stainforthia feylingi, Bolivina arctica, Triloculina trihedra, and scarce Oridorsalis umbonatus. These foraminifera species are typical of Holocene to Pleistocene Arctic shelf and slope environments. They are regarded as opportunists associated with sea ice–influenced environments, whereas O. umbonatus is ubiquitous in deeper water settings globally (Seidenkrantz, 2013). Agglutinated benthic species are recorded in one sample (400-U1603B-27F-CC). These benthic assemblages are similar to those found by Kaminski et al. (1989) at Ocean Drilling Program Site 645 and Feyling-Hansen (1976) in the Clyde Foreland Formation (western Baffin Bay), and they are consistent with a Pleistocene age.

In the foraminifera-rich samples, foraminifera were also detected in the sedimentology smear slides and the diatom and dinoflagellate slides. These contained a number of well-preserved examples of N. pachyderma as juveniles, having only six to seven chambers in the test, and embryonic stages, involving combinations of two or three small globular chambers (Figure F12C). The Sample 400-U1603A-11H-1, 52–53 cm, diatom slide contained specimens of the benthic foraminifera B. elegantissima and B. arctica (Figure F12D, F12E). In five cases, foraminifera appeared in palynology slides although they did not appear in the >63 µm residues (Samples 3H-2, 56–58 cm, and 11H-1, 6–8 cm, and 400-U1603B-4H-CC, 21F-1, 42–44 cm, and 26F-3, 68–70 cm). These slides record common to abundant occurrences of foraminifera specimens smaller than the typical 63 µm preparations routinely examined by the foraminifera team. This finding of small foraminifera species and subadult forms in superfine-fraction preparations in this slope setting has potential ecological/environmental implications and raises questions about calcite preservability on the northwest Greenland margin. It also has relevance to questions about the life history and transportation of N. pachyderma in extreme Arctic slope and shelf settings, including the possibility of planktonic foraminifera nurseries or refugia in such regions or advection of juvenile forms by Atlantic water entering Baffin Bay.

The general scarcity of foraminifera at Site U1603 suggests combinations of calcite dissolution and climatic conditions prohibitive to planktonic foraminifera production and/or preservation in seafloor sediments or the sediment pile. Extensive seafloor dissolution of foraminifera shells in Baffin Bay has been observed under recent interglacial conditions, despite the fact that planktonic foraminifera live in the water column (Stehman, 1972). Even where we do find foraminifera, it is possible that dissolution-susceptible species, including Globigerina bulloides, which occurs in the water column of Baffin Bay (Stehman, 1972), have been selectively dissolved.

Overall, the foraminifera from Site U1603 yielded species consistent with a Pleistocene age. Although the sporadic foraminifera occurrence is not appropriate for identifying specific bioevents useful for dating, the occurrence of a mature N. pachyderma assemblage in Section 400-U1603D-13R-CC (377.86 m CSF-A) implies the cored sequence down to that level is younger than 1.82 Ma. This constraint is based on the established timing of the first common occurrence of N. pachyderma biohorizons (B Common N. pachyderma sinistral), which has been calibrated to the paleomagnetics in the North Atlantic (Expedition 395).

4.1.2. Diatoms

We examined 118 Site U1603 samples, consisting primarily of core catcher samples, for diatoms. Diatoms were observed in trace amounts in seven samples at Site U1603. Except in Samples 400-U1603A-1H-1, 1 cm, 5H-6, 12–13 cm, 11H-1, 52–53 cm, and 11H-1, 126–127 cm; 400-U1603B-3H-CC; 400-U1603D-13R-4, 119–120 cm; and 400-U1603F-1H-1, 0 cm, the great majority of core catcher and section-half samples are virtually barren of diatoms (Figure F11). Only fragments of diatoms, which could not be confidently identified, were observed in a few samples. The morphology of most of the fragments indicates that they were probably derived from Coscinodiscus species.

Mudline Samples 400-U1603A-1H-1, 1 cm, and 400-U1603F-1H-1, 0 cm, contain trace to rare amounts of moderately to poorly preserved diatoms, including Actinocyclus curvatulus, Rhizosolenia hebetata f. hebetata, Chaetoceros spp. and resting spores, Melosira arctica, and Navicula spp. Observed species are characteristic of the modern assemblages living in the Arctic region. Coscinodiscus marginatus is present in trace amounts in Samples 400-U1603A-5H-6, 12–13 cm, and 11H-1, 52–53 cm. These samples also contain trace amounts of Coscinodiscus species fragments. We also observed a single specimen of Coscinodiscus oculus-iridis in Sample 11H-1, 52–53 cm. Two specimens of Stephanopyxis turris were observed in Section 400-U1603B-3H-CC. A few specimens of Podosira sp. (montagnei?) were seen in Samples 400-U1603A-11H-1, 52–53 cm, and 11H-1, 126–127 cm; 400-U1603B-3H-CC; and 400-U1603D-13R-4, 119–120 cm.

Trace occurrence and poor preservation of diatoms at Site U1603 preclude any stratigraphic analysis (Figure F11). The specimens seen are typical of Arctic environments, except S. turris, although too few specimens were observed to discern paleoenvironmental conditions at Site U1603. The virtual absence of diatoms in these sediments may have paleoceanographic significance or may signify extensive dissolution and/or diagenesis.

4.1.3. Palynology

In total, 52 core catcher samples and 51 additional samples from targeted intervals were processed following the procedure described in Biostratigraphy in the Expedition 400 methods chapter (Knutz et al., 2025).

Overall, palynomorphs, and notably the dinocysts among them, were found to be scarce except for a few intervals, and no quantitative analyses were conducted on board. Occurrences of palynofacies categories and palynomorphs for all samples from Site U1603 are listed in Table T6.

All dinoflagellate cysts species observed in the analyzed material are consistent with a Pleistocene age. Preservation of in situ dinocysts is good in all samples, although abundances are low across the entire studied interval. Rarity of palynomorphs in the Quaternary in Arctic marine settings can be attributed to the small number of dinoflagellates around the Arctic that form fossilizable cysts (Okolodkov, 1998) and the general ecological preference of dinoflagellates for warmer waters (e.g., de Vernal et al., 2013).

Dinocyst species belonging to the genus Brigantedinium spp. are present in 47 of the 103 samples from throughout the entire interval (Figure F11). Highest abundances of Brigantedinium spp. are observed in Sample 400-U1603A-6H-CC and samples from Sections 11H-1 and 12H-1; Sample 400-U1603B-8F-CC; and Samples 400-U1603D-5F-CC, 6F-CC, and 16R-CC. Other species of dinocysts identified include Echinidinium sleipnerensis, Echinidinium delicatum, Echinidinium granulatum, Islandinium brevispinosum, and Islandinium minutum (Figure F14A, F14B, F14D, F14E). Intervals with higher abundances of these dinocysts include Samples 400-U1603A-3H-2, 56–68 cm, and 400-U1603D-8R-5, 37–39 cm, and samples from Sections 400-U1603A-11H-1, 400-U1603D-5R-CC, and 400-U1603A-10H-CC. In Sample 3H-2, 56–68 cm, a type of Echinidinium with slightly fewer and longer processes than E. sleipnerensis is present. This specimen resembles Echinidinium sp. A (Radi et al., 2013), which was previously observed in last interglacial (Upper Pleistocene) deposits from the Norwegian Sea (Radi et al., 2013).

Other in situ palynomorphs include Leiosphaeridia in 29 of the 103 samples. This acritarch is most abundant at the contact margin between seasonal sea ice and pack ice in the Arctic (Mudie, 1992). Highest abundances of Leiosphaeridia are found in Samples 400-U1603B-8F-CC; 400-U1603D-5R-CC; 400-U1603C-9R-CC; 400-U1603A-11H-3, 90–92 cm, and 10H-CC; and all samples from Section 400-U1603C-5R-1. Additionally, the prasinophyte algae Cymatiosphaera (Figure F14C) is found in Samples 400-U1603A-11H-3, 111–113 cm, and 10H-CC.

In addition to in situ palynomorphs, varying abundances of reworked (mostly terrestrial) palynomorphs are present in all samples, which is a common characteristic of sites at continental margins proximal to ice sheets, like Site U1603 (Smelror, 1999). The highest rates of terrestrial reworking are found in Samples 400-U1603B-26F-CC; 400-U1603C-5R-1, 56–58 cm; 400-U1603B-21F-1, 77–79 cm; and 400-U1603A-11H-1, 126–128 cm, 11H-3, 80–82 cm, 11H-3, 90–92 cm, and 11H-3, 111–113 cm. These include bisaccate pollen, other gymnosperm pollen, and wide varieties of trilete fern spores (Figure F14A). Future study by a pollen and spore specialist would be a valuable contribution to constrain the age of the reworked sediments.

In addition to terrestrial reworking, some samples yielded large amounts of marine reworking, represented by high numbers of dinocysts of a Paleogene age. The assemblage includes various species belonging to the genera Cordosphaeridium, Wetzelliella (Figure F14F), Spiniferites, and Hystrichosphaeridium (Figure F14G), among others. Two intervals that are marked by this pulse of reworking are from Section 400-U1603A-11H-3 and Sample 400-U1603B-21F-1, 77–79 cm. These reworked sediments have a great potential to further constrain the source of reworked material.

4.1.3.1. Provenance study

To constrain the origin of the reworked marine sediments of Paleogene age, clasts from one interval have been sampled and processed separately using the same method that was used for other palynology samples. Clasts sampled originated from Sample 400-U1603C-5R-1, 45–47 cm. One brown sedimentary clast and one black sedimentary clast were analyzed. The brown clast contains abundant organic matter aggregates, plant material, and some poorly preserved bisaccate pollen. This implies a terrestrial source for which the age could not be constrained. The black clast consists of a variety of different minerals, a few organic matter aggregates, and rare phytoclasts. Palynomorphs are very rare, although one poorly preserved small cyst was identified. The source of this clast could not be determined based on these palynomorphs.

4.1.4. Marine sedimentary ancient DNA

A mudline sample (~10 g) was collected as a modern reference from Hole U1603A. Samples for sedimentary ancient DNA (sedaDNA) analysis were collected from Hole U1603E (Table T7) down to ~14 m CSF-A (6 samples on the catwalk; 3 in split core sections) and Hole U1603F (Table T8 down to ~132 m CSF-A (38 samples on the catwalk; 13 in split core sections) following the catwalk and the split core sampling methodologies (see Biostratigraphy in the Expedition 400 methods chapter [Knutz et al., 2025]). On the catwalk, samples were usually taken at the bottom of Sections 1, 3, and 5 if the sections were available and the section bottom was undisturbed. Additional samples were collected from the working half of split sections targeting nonstratified mud layers with few or no clasts, characterized by low MS and low NGR, predominantly above and/or below calcareous layers. Considering the lithology, all samples from Hole U1603E were taken within mud layers, and for Hole U1603F, 15 sedaDNA samples were taken within interlaminated sand(stone) and mud(stone), 1 within interlaminated sand(stone) and mud(stone) with dispersed clasts, 3 within interbedded sand(stone) and mud(stone), 25 in mud, 2 in mud with sand, 1 in sandy mud, 3 in mud with dispersed clasts, and 1 in mud with common clasts. All samples were immediately stored at −86°C. A total of 12 tracer samples were taken for Hole U1603E (Table T9) and 69 for Hole U1603F (Table T10). Trace amounts of perfluorodecalin (PFD) tracer were detected in the external sample from the bottom of Section 400-U1603E-1H-1 and in samples taken from liquid at the top of cores from Hole U1603F, confirming the arrival of PFD at the drill bit (Figure F15). Overall, these results suggest a low risk of contamination by drill fluids with the APC system.

5. Paleomagnetism

Pass-through paleomagnetic measurements from Site U1603 were performed using the superconducting rock magnetometer (SRM) to investigate the natural remanent magnetization (NRM) on a total of 313 archive section halves. Measurements were not made on 16 archive section halves that had highly disturbed sediments, and no pass-through measurements were made on core catcher samples. All measurements on section halves were made at 2 cm intervals; we measured the initial magnetization and the magnetization following stepwise peak alternating field (AF) demagnetizations at 5, 10, 15, and 20 mT.

A total of 188 discrete cube samples were taken from the working section halves from Holes U1603A–U1603D. Generally, we collected one sample per section, avoiding visually disturbed intervals. Note that in paleomagnetic practice, samples are the objects that are taken (sampled) and specimens are the objects that are measured. In this case, the two objects are the same. We measured 54 specimens on the AGICO JR-6A spinner magnetometer and 146 specimens on the SRM. Some specimens were measured on both instruments to ensure cross-calibration.

5.1. Discrete sample measurements

A total of 188 discrete cube samples were collected from working section halves: 73 from Hole U1603A, 79 from Hole U1603B, 13 from Hole U1603C, and 23 from Hole U1603D. All were measured after stepwise demagnetization up to a peak field of 20 mT on either the JR-6A or the SRM. Of these, 71 specimens were measured after stepwise AF demagnetizations up to a peak field of 80 mT to assess the demagnetization behavior at higher peak fields. Examples of Zijderveld diagrams (Zijderveld, 1967) are shown in Figure F16 for normally (Figure F16A, F16B) and reversely magnetized specimens (Figure F16C, F16D), along with plots of the remaining remanence versus AF demagnetization step (Figure F16E–F16H). In both normal and reversed polarity intervals, the drill string overprint is typically removed by 15 mT; the preliminary magnetostratigraphy is based on the inclination from measurements of the 20 mT AF demagnetization step. Because the cores are not azimuthally oriented and the field at the site latitude is nearly vertical, declination was not used to constrain polarity.

We measured anisotropy of MS (AMS) and volume-normalized bulk MS using the AGICO MFK2 Kappabridge on 188 discrete specimens. The AMS data are reduced to a 3 × 3 tensor with eigenvalues (τ1, τ2, and τ3) and eigenvectors (V1, V2, and V3), where τ1 is the maximum eigenvalue associated with eigenvector V1 and τ1 > τ2 > τ3. These data provide useful information about possible disturbance of the specimens from geological processes, core recovery, or sampling. In an undisturbed sedimentary fabric, τF is approximately equal to τ2, and the ratio can be used as a measure of disturbance. In Figure F17A, we plot the ratio of the two as a cumulative distribution function. For values close to unity, the sediments are undisturbed, but for ratios larger than about 1.02, we can infer that the sediments were disturbed either by sedimentary processes (e.g., slumping) (Schwehr and Tauxe, 2003) or by coring. We use this eigenvalue ratio to assign disturbance and plot the disturbed specimens as Xs.

We show the directions of the eigenvectors in Figure F17B. The direction of the minimum axis (blue circles) is expected to be vertical (center of the diagram) in most sediments, and this is the case for the vast majority of our specimens. However, some are quite deflected from the vertical; these likely suffered some disturbance of the sedimentary fabric related to uparching of the core, and their directions could therefore be suspect.

To examine the behavior of the eigenparameters versus depth, we plot the eigenvalues in Figure F18A, along with the ratio τ1/τ (L, lineation parameter of Balsley and Buddington [1960]; see also Chapter 13 of Tauxe [2010]) in Figure F18C and the inclination of V3 in Figure F18B. Intervals with values of L significantly different from unity (e.g., Core 400-U1603A-12H) are likely disturbed either from sedimentary processes (slumping) or coring disturbance, and these are plotted as Xs in Figure F18A.

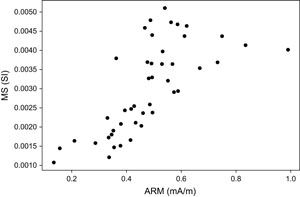

Anhysteretic remanent magnetization (ARM) was also measured on a subset of 45 discrete specimens from Holes U1603A and U1603B. We imparted an ARM with a peak 50 mT AF and 50 µT direct current (DC) field on specimens that had been demagnetized on all three axes at 80 mT. These measurements were compared with volume-normalized bulk MS (Figure F19). The relationship between ARM and MS is quasilinear, which suggests that the concentration of magnetic minerals is the primary control on both measurements and supports the use of normalized remanence for estimating relative paleointensity (RPI) (see Age model).

5.2. Archive-half measurements

Site U1603 archive section halves were stepwise demagnetized to 20 mT to remove the drilling overprint. Data were filtered as follows:

- All measurements within 10 cm of section ends were deleted to remove the edge effects associated with pass-through measurements.

- Intervals with drilling disturbances as defined by the disturbance intensity code of “moderately disturbed” or greater (see Lithostratigraphy in the Expedition 400 methods chapter [Knutz et al., 2025]) were removed.

- Core linescan images and X-radiographs in intervals of suspect directions were examined to assess where lithologic features such as dropstones or concretions necessitated removal of intervals.

Data from the 20 mT demagnetization step are shown in Figures F20, F21, F22, F23, F24, and F25. Unfiltered data are plotted with gray dots, and filtered data are plotted with black dots. Inclination and declination of discrete specimens, calculated from the remanent magnetization measured after the 20 mT AF demagnetization step, are shown as red stars if they were deemed undisturbed using the AMS eigenvalue discrimination approach; those that were disturbed are plotted as Xs.

Inclinations from the filtered archive section half 20 mT step data are shown as kernel density plots in Figure F26 and support the assumption that periods of both normal and reversed polarity were recovered at Site U1603. Most inclination magnitudes fall under expected (geocentric axial dipole [GAD]) values for the latitude of Site U1603 during normal (positive inclinations) and reversed (negative inclinations) polarities.

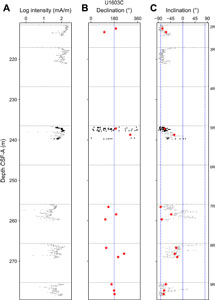

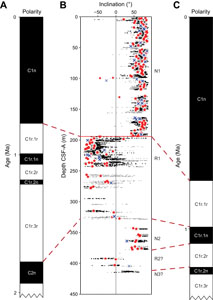

5.3. Magnetostratigraphy

Preliminary magnetostratigraphic interpretations are based on inclinations calculated from archive section half and discrete specimen measurements from the 20 mT AF demagnetization step (with disturbed fabrics indicated with an X in Figure F27). We observe an interval of normal polarity (Polarity Zone N1 in Figure F27) from the surface to 193.8 m CSF-A in Hole U1603B. Fully reversed inclinations (less than −45°) are achieved by 194.08 m CSF-A, and we pick the boundary at 194 m CSF-A (Table T11).

In the lower part of Hole U1603B, starting at about 200 m CSF-A, we observe somewhat shallow inclinations in the pass-through archive section half measurements, but they are in intervals of interlaminated mud and sand, as well as dispersed clasts. Discrete specimens from these cores (red stars in Figure F27), chosen to avoid sandy intervals and clasts, show steeper negative inclinations consistent with a reversed polarity. It is also possible that this period may be associated with an excursion or coring disturbance, as indicated by the X symbols.

We define the transition in inclinations back to normal polarity in Section 400-U1603C-8R-3 at 327 m CSF-A (Polarity Zone N2 in Figure F27). Recovery was poor in Hole U1603D, but the normal polarity interval appears to continue through at least Core 13R. We define the lower boundary of Polarity Zone N2 at 393 m CSF-A in Hole U1603D, with a potential interval of reversed polarity (Polarity Zone R2) below. A third normal interval (Polarity Zone N3) may appear briefly at 411 m CSF-A in Hole U1603D (Figure F27).

We identified two possible scenarios for correlating the magnetostratigraphic patterns measured below the Brunhes Chron to the chrons defined in the geomagnetic polarity timescale (GPTS) of Ogg (2020). The first scenario (Figure F27A) correlates the interval of intermediate directions within Polarity Zone R1 with the Jaramillo Subchron (C1r.1n) and Polarity Zone N2 with the Olduvai Subchron (C2n). The second (preferred; see Age model) scenario (Figure F27C) correlates Polarity Zone N2 with the Jaramillo Subchron (C1r.1n) and Polarity Zone N3 tentatively with the Cobb Mountain Subchron (C1r.2n) (Table T11).

6. Physical properties

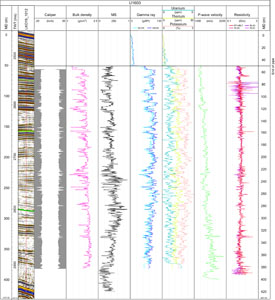

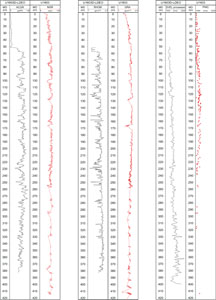

Physical property data were acquired on all cores from Holes U1603A–U1603D using the Whole-Round Multisensor Logger (WRMSL) for wet bulk density from gamma ray attenuation (GRA), MS, and P-wave velocity (using the P-wave logger [PWL]) at a 2 cm resolution. We also measured NGR in all sections longer than 50 cm. Thermal conductivity was measured in one whole-round section per core wherever possible. It was measured on the working section halves if the sediment was too hard or the whole-round measurement readings were unreliable. For Holes U1603E and U1603F, only NGR and low-resolution (5 cm) MS were logged for stratigraphic correlation purposes. The cores from these sites were sampled for sedaDNA; thus, the GRA source was kept inactive during WRMSL logging to avoid possible effects on the DNA preservation. Equalization to room temperature was not reached because of the fast track logging for stratigraphic correlation purposes. Thus, PWL measurements were not made.

After the whole rounds were split into halves, we acquired X-ray imaging of the archive halves of every core. The Section Half Multisensor Logger (SHMSL) was used to measure point MS (MSP) and color reflectance using the L*a*b* color system, and the red-green-blue color space (RGB) of the sediments was captured with the Section Half Imaging Logger (SHIL). In addition, we determined P-wave velocities at discrete points on the working section halves for almost all cores at Site U1603. In general, we measured P-wave velocity in three sections per APC core and two sections per HLAPC and rotary core barrel (RCB) core. P-wave caliper (PWC) measurements of P-wave velocity were done in all sections from Holes U1603E and U1603F to compensate for the lack of PWL measurements. Measurements were taken at variable intervals to accommodate lithologic variations. Two moisture and density (MAD) samples per core were taken and processed for Holes U1603A–U1603D to obtain discrete wet bulk density, dry bulk density, grain density, and porosity. No MAD samples were taken for Holes U1603E and U1603F.

Prominent variations in physical property values occur at similar depths in NGR, density, and MS signals and are associated with major lithologic changes in the cores. More uniform lithologies are reflected by more monotonous physical property signals. The sensors worked correctly, and the data are of good quality. Accordingly, the physical properties obtained from Site U1603 provide valid and reproducible information on sediment composition and its variability for all cores.

6.1. Physical property measurements and measurement intervals

High-resolution physical property measurements were made on all core sections and most core catchers from Holes U1603A–U1603D to provide basic information on sediment composition and variability. The WRMSL measured bulk density by GRA, MS, and compressional P-wave velocity on the PWL at 2 cm intervals. PWL measurements were not obtained on cores from Holes U1603E and U1603F because logging lacked the time for equilibration to room temperature (fast tracked for stratigraphic correlation) required to obtain reliable readings of compressional wave velocity. In general, PWL readings are robust on cores recovered with the APC system, but material recovered with the RCB system has a slightly smaller core diameter and does not fill the liner entirely. The lack of proper contact between the caliper and the sediment leads to large standard deviations in the measurements. Thus, PWL values are only of use in correlation with PWC velocities. GRA measurements were not made on cores from Holes U1603E and U1603F because they were sampled for sedaDNA. For these cores, only MS was measured on the WRMSL at 5 cm resolution for correlation proposes. For holes with sedaDNA sampling, measurements of MS were made on the WRMSL in Special Task Multisensor Logger (STMSL) (fast track) mode and are noted as such in the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) database; however, for simplicity in this report, they are referred to as WRMSL measurements. NGR was measured with a counting period of 300 s at 10 cm intervals (see Physical properties in the Expedition 400 methods chapter [Knutz et al., 2025]) on all cores from Site U1603. Thermal conductivity was measured using the TK04 (Teka Bolin) system in the whole-round sections wherever possible. However, it was obtained with a puck probe from the working section halves where sediment was too hard to penetrate with the needle probe or if the readings were not accurate. Needle and puck probes provide comparable data.

After the cores were split, the section halves were X-rayed and thermal conductivity was measured, unless this could be performed on the whole-round section. PWC velocity was acquired in three working sections per core for Holes U1603A–U1603D and all the working sections from Holes U1603E and U1603F. Lithology and core disturbance prohibited the collection of PWC values on 2 cores out of 13 from Hole U1603A, 2 cores out of 26 from Hole U1603B, 3 cores out of 9 from Hole U1603C, 6 cores out of 17 from Hole U1603D, and 3 cores out of 7 from Hole U1603E. For Holes U1603C and U1603E, the cores missing PWC measurements are those with no recovery. MSP and color reflectance were measured at 2 cm increments using the SHMSL, and digital color imaging was measured with the SHIL on all archive section halves. Additionally, discrete samples from all cores from Holes U1603A–U1603D were taken for MAD measurements as two samples per core, ideally representing different lithologies. They were processed on board to determine water content, wet bulk density, dry bulk density, porosity, and grain density.

All physical property analyses were carried out except the PWC measurements mentioned above. Low-quality PWL measurements were noted on RCB cores in Holes U1603C and U1603D. Core disturbances, such as upbowing of layers, did not diminish the quality of the physical property data in a way that prevents meaningful core-seismic integration.

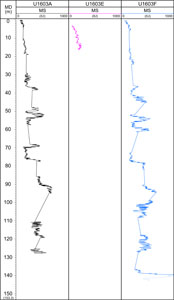

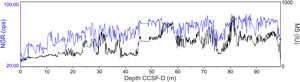

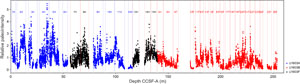

6.1.1. Whole-Round Multisensor Logger measurements

Results from WRMSL measurements for Holes U1603A–U1603D are compiled in Figure F28. We measured high-resolution data (2 cm intervals) for all the core sections and the majority of the core catchers. All cores from Holes U1603A–U1603D rested for around 5 h to equilibrate to room temperature (~19°C) before logging in the WRMSL. We measured NGR and low-resolution MS (5 cm intervals) for all cores from Holes U1603E and U1603F upon arrival to the laboratory for stratigraphic correlation purposes (Figure F29). The logs described in this chapter have undergone preliminary processing including clipping, despiking, and smoothing. A positive correlation is found between density and NGR counts, as well as between density and MS downhole, likely in response to lithology changes at Site U1603 (Figures F28, F29, F30). The correlation between these physical properties distinguishes four physical properties units at Site U1603; the main signatures of those units are summarized in Table T12.

6.1.1.1. Gamma ray attenuation bulk density

Wet bulk densities range 1.3–2.1 g/cm3 with a mean value of 1.9 g/cm3. Wrapping cyclicity is observed downhole for GRA bulk density, along with a downhole trend to increasing values above Core 400-U1603B-10F (~165 m CSF-A), whereas below this depth, GRA baseline values show a slight decrease with depth. The lowest values are found in Cores 2H (~120 m CSF-A), 9F (~160 m CSF-A), and 400-U1603D-6R (305 m CSF-A), and the highest values are located between 130 and 180 m CSF-A (Figure F28). GRA bulk density values generally agree with calculated densities from the MAD discrete samples, except in the interval between 35 and 155 m CSF-A, where MAD values are consistently lower than GRA density values. The largest differences are up to 0.2 g/cm3.

6.1.1.2. Magnetic susceptibility

MS is sensitive to the concentration and type of magnetic minerals deposited in the sediments. Although it usually appears as sharp peaks of high-amplitude variability, MS also tracks lithologic changes. Values at Site U1603 range 49 × 10−5 to 821 × 10−5 SI with a mean of 391 × 10−5 SI (Figures F28, F29). The baseline of the signal presents high-amplitude variability (up to 230 × 10−5 SI), particularly between 20 and 165 m CSF-A. There is a general decrease in the baseline of MS downhole.

The highest MS values are found in Core 400-U1603A-9H (>800 × 10−5 SI), and the lowest values are observed in Cores 1H–3H and 400-U1603B-26F (~80 × 10−5 SI). Generally, we observe a strong correlation in the variability with depth of all physical properties determined with the WRMSL (Figure F29). However, MS varies considerably within intervals of high NGR and GRA bulk density (Figure F28).

6.1.1.3. P-wave velocity using the P-wave logger

P-wave velocities measured with the PWL show unreliable values on sections with cracks or poor contact between the sediment and the liner. Thus, measurements on cores recovered with the APC or HLAPC systems are more reliable than those drilled with the XCB or RCB systems. However, the measurements are generally good and range 1470–1900 m/s. PWL values gradually increase downhole, exceeding 1800 m/s below 230 m CSF-A (Figure F28). The lowest velocity values are observed for Cores 400-U1603A-1H and 2H (above 5 m CSF-A) and the highest for Core 400-U1603B-24F downward (below 230 m CSF-A).

6.1.2. Natural gamma radiation

NGR values display high-amplitude variability with cyclic changes at Site U1603 (Figures F28, F29). NGR values oscillate between 30 and 86 counts/s with a mean of 68 counts/s. The baseline of the signal responds to high NGR values between Cores 400-U1603A-6H and 400-U1603B-21F (40–220 m CSF-A). In this interval, the lowest counts in NGR are for Cores 400-U1603A-8H, 11H, 400-U1603B-3H, and 9F. The NGR baseline is lower in cores from Holes U1603C and U1603D (220–422 m CSF-A).

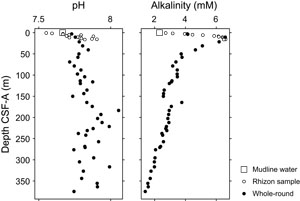

6.1.3. Thermal conductivity