Reagan, M.K., Pearce, J.A., Petronotis, K., and the Expedition 352 Scientists, 2015

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 352

publications.iodp.org

doi:10.14379/iodp.proc.352.101.2015

Expedition 352 summary1

M.K. Reagan, J.A. Pearce, K. Petronotis, R. Almeev, A.A. Avery, C. Carvallo, T. Chapman, G.L. Christeson, E.C. Ferré, M. Godard, D.E. Heaton, M. Kirchenbaur, W. Kurz, S. Kutterolf, H.Y. Li, Y. Li, K. Michibayashi, S. Morgan, W.R. Nelson, J. Prytulak, M. Python, A.H.F. Robertson, J.G. Ryan, W.W. Sager, T. Sakuyama, J.W. Shervais, K. Shimizu, and S.A. Whattam2

Keywords: International Ocean Discovery Program, IODP, JOIDES Resolution, Expedition 352, Izu-Bonin-Mariana fore arc, Site U1439, Site U1440, Site U1441, Site U1442, subduction initiation, magma genesis, ophiolites, basalt, boninite, high-magnesium andesite, volcanic rocks, dikes, drill core

MS 352-101: Published 29 September 2015

Abstract

The objectives for International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 352 were to drill through the entire volcanic sequence of the Bonin fore arc to

- Obtain a high-fidelity record of magmatic evolution during subduction initiation and early arc development,

- Test the hypothesis that fore-arc basalt lies beneath boninite and understand chemical gradients within these units and across the transition,

- Use drilling results to understand how mantle melting processes evolve during and after subduction initiation, and

- Test the hypothesis that the fore-arc lithosphere created during subduction initiation is the birthplace of suprasubduction zone ophiolites.

Expedition 352 successfully cored 1.22 km of igneous basement and 0.46 km of overlying sediment, providing diverse, stratigraphically controlled suites of fore-arc basalt (FAB) and boninites related to seafloor spreading and earliest arc development. FAB and related rocks were recovered at the two deeper water sites (U1440 and U1441) and boninites and related rocks were recovered at the two sites (U1439 and U1442) drilled upslope to the west. FAB lavas and dikes are depleted in high–field strength trace elements such as Ti and Zr relative to mid-ocean-ridge basalt but have relatively diverse concentrations of trace elements because of variation in degrees of melting, and potentially, the amount of subducted fluids involved in their genesis. FAB are relatively differentiated, and average degree of differentiation increases with depth, which is consistent with crystal fractionation in a persistent magma chamber system beneath a spreading center. Holes U1439C and U1442A yielded entirely boninite differentiation series lavas that generally become more primitive and have lower TiO2 concentrations upward. The presence of dikes at the base of the sections at Sites U1439 and U1440 provides evidence that boninitic and FAB lavas are both underlain by their own conduit systems and, therefore, that FAB and boninite group lavas are likely offset more horizontally than vertically. We thus propose that seafloor spreading related to subduction initiation migrated from east to west after subduction initiation and during early arc development. Initial spreading was likely rapid, and an axial magma chamber was present. Melting was largely decompressional during this period, but subducted fluids affected some melting. As subduction continued and spreading migrated to the west, the embryonic mantle wedge became more depleted and the influence of subducted constituents dramatically increased, causing the oceanic crust to be boninitic rather than tholeiitic. The general decrease in fractionation upward in the boninite holes reflects the eventual disappearance of persistent magma chambers, either because spreading rate was decreasing with distance from the trench or because spreading was succeeded by off-axis magmatism trenchward of the ridge. The extreme depletion of the sources for all boninitic lavas was likely related to the incorporation of mantle residues from FAB generation. This mantle depletion continued during generation of lower silica boninitic magmas, exhausting clinopyroxene from the mantle such that the capping high-silica, low-titanium boninites were generated from harzburgite.

Additional results of the cruise include recovery of Eocene to recent deep-sea sediment that records variation in sedimentation rates with time resulting from variations in climate, the position of the carbonate compensation depth, and local structural control. Three phases of highly explosive volcanism (latest Pliocene to Pleistocene, late Miocene to earliest Pliocene, and Oligocene) were identified, represented by 132 graded air fall tephra layers. Structures found in the cores and reflected in seismic profiles show that this area had periods of normal, reverse, and strike-slip faulting. Finally, basement rock P-wave velocities were shown to be slower than those observed during logging of normal ocean crust sites.

Background

Izu-Bonin-Mariana system

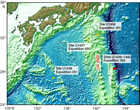

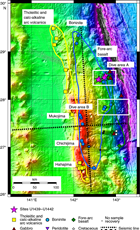

The Izu-Bonin-Mariana (IBM) system is the type locality for studying oceanic crustal accretion immediately following subduction initiation. It is sufficiently old that it carries a full record of the evolution of crustal accretion from the start of subduction to the start of normal arc volcanism and sufficiently young that the key features have not been excessively disturbed by subsequent erosion or deformation. Intraoceanic arcs are built on oceanic crust and are sites of formation of juvenile continental crust (Rudnick, 1995; Tatsumi and Stern, 2006). Most active intraoceanic arcs are located in the western Pacific. Among these, the IBM system stands out as a natural scientific target. This predominantly submarine convergent plate boundary is the result of ~52 My of subduction (Ishizuka et al., 2011; Reagan et al., 2013) of the Pacific plate beneath the eastern margin of the Philippine Sea plate. Stretching for 2800 km from the Izu Peninsula, Japan, to Guam, USA, the IBM system (summarized in Stern et al., 2003) has been extensively surveyed and has become an important natural laboratory for International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) expeditions (Figure F1) aimed at understanding subduction initiation, arc evolution, and continental crust formation. A scientific advantage of studying the IBM system is its broad background of scientific investigation resulting from its designation as a focus site by the US National Science Foundation MARGINS-Subduction Factory experiment and similar efforts in Japan. We know when subduction and arc construction began at the IBM system, even if the precise paleogeography is controversial, and there is a good time-space record of crustal development.

Petrologic evolution

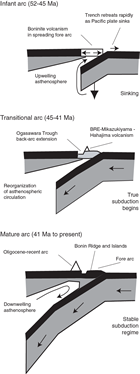

The petrologic evolution of early stage magmatism in the IBM arc has been reconstructed mainly based on volcanic sections that are exposed on the fore-arc islands (Bonin Islands and Mariana Islands) and that have been recovered from Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) fore-arc drill sites. Recent dredging and submersible studies have provided additional information. Consequently, we were able to predict the sequence of magmas likely to characterize the drill site and its surrounding region, which developed after subduction initiation and prior to establishment of a stable magmatic arc to the west by the late Eocene. The physical evolution of the fore arc and its associated lavas reflects the reorganization of mantle convection and slab-derived fluid flow in response to the changing behavior of the sinking Pacific plate. This evolution, from initial seafloor spreading and eruption of mid-ocean-ridge basalt (MORB)-like tholeiites to eruption of boninites to fixing of the magmatic arc ~150 km west of the trench (separated by a broad, dead fore arc), took 7–8 million years (Ishizuka et al., 2011). The process is reflected in the succession of igneous rocks of the Bonin Ridge, which is described in greater detail below and depicted in the time-space diagram (Figure F2).

Early subduction-related volcanism

Diving and dredging on the fore-arc slope east of the Bonin Ridge and south of Guam recovered basaltic rocks from stratigraphic levels below boninite. These basalts have chemical compositions that are similar to those of normal MORB (N-MORB). However, they are not identical, and hence the term “fore-arc basalt (FAB)” was coined by Reagan et al. (2010) to highlight their distinctive setting and to emphasize that, in detail, FAB is a different magma type from MORB. Most of the reliable 40Ar/39Ar ages and U-Pb zircon ages of FAB are identical within error in both locations and indicate that FAB magmatism occurred at ~51–52 Ma, preceding boninite eruption by 2–4 million years (Ishizuka et al., 2011; Reagan et al., 2013). Lavas with compositions transitional between FAB and boninites from DSDP Leg 60 Site 458 in the Mariana fore arc were dated at 49 Ma (Cosca et al., 1998). FAB and related gabbros are thought to relate to the first magmas produced as the IBM subduction zone began to form (Reagan et al., 2010).

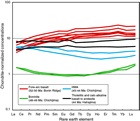

Geochemical data show that FAB magmas have light rare earth element–depleted rare earth element (REE) patterns, indicating derivation from a moderately depleted lherzolitic upper mantle, similar to that responsible for generating MORB (Figure F3). FAB in the IBM, however, has low Ti/V (14–16), a diagnostic ratio (Shervais, 1982) that distinguishes FAB from subducting Pacific MORB (Ti/V = 26–32) and from Philippine Sea back-arc lavas (Ti/V = 17–25) (Figure F4). Chemically and petrographically, Bonin Ridge FAB is indistinguishable from Mariana FAB. This implies that FAB tholeiitic magmatism was associated with fore-arc spreading along the length of the IBM arc. Low concentrations of incompatible elements and low trace element ratios such as Ti/V imply that FAB magmas were derived from more depleted mantle and/or were larger degree mantle melts than typical Philippine Sea MORB (Reagan et al., 2010).

Pb isotopic compositions of FAB from the Bonin fore arc show that they are, like other IBM arc and back-arc magmas, derived from a mantle with Indian Ocean characteristics, as demonstrated by high Δ8/4 Pb compared to Pacific MORB (Ishizuka et al., 2011). Isotopic characteristics indicate some differences between the mantle sources of Philippine Sea MORB and FAB, including distinctly higher 87Sr/86Sr and 206Pb/204Pb (Figure F5), which may imply the presence of lithospheric mantle with inherited enrichment (Parkinson et al., 1998). Most significantly, incompatible trace elements derived from subducted crust do not unambiguously affect the source region of most FAB, although some FAB lavas from the Mariana fore arc have Pb isotopic compositions consistent with a weak influence of subducted Pacific crust (Reagan et al., 2010). Differences in isotopic and trace element characteristics between IBM FAB and MORB including that from the Philippine plate strongly imply that FAB do not represent preexisting ocean basin or back-arc basin crust trapped prior to subduction initiation, as originally concluded by Johnson and Fryer (1990) and DeBari et al. (1999) for MORB-like tholeiites recovered from the Mariana and Izu inner trench walls.

Lavas with compositions that transition upward between FAB and boninite were recovered at Sites 458 and 459 in the Mariana fore arc and illustrate that FAB and boninite are genetically linked (Reagan et al., 2010). The oldest of these lavas have REE patterns similar to those of MORB but are more enriched in silica and have higher concentrations of “fluid-soluble” elements such as K, Rb, U, and Pb than FAB. These lavas also have Pb isotopic compositions that are more similar to lavas from the Pacific than to those from the Indian plate, supporting the contention that subducted fluids were involved in their genesis. The youngest lavas at Site 458 are strongly depleted in REE, somewhat resembling boninites but less magnesian and more calcic.

Boninite volcanism follows FAB volcanism as an integral part of the evolution of the nascent subduction zone. The type locality of boninite is in the Bonin (Ogasawara) Islands, an uplifted segment of the IBM fore arc. Boninites are better exposed on the Bonin Islands than anywhere else in the world, particularly on the island of Chichijima. 40Ar/39Ar dating indicates that boninitic volcanism on Chichijima took place briefly during the Eocene, between 46 and 48 Ma (Ishizuka et al., 2006). A slightly younger volcanic succession is exposed along the Bonin Ridge, including 44.74 ± 0.23 Ma boninite-series lavas from the Mikazukiyama Formation, the youngest volcanic sequence on Chichijima, and 44.0 ± 0.3 Ma tholeiitic to calc-alkaline andesite from Hahajima. Four submersible Shinkai 6500 dives on the Bonin Ridge Escarpment mapped an elongate constructional volcanic ridge atop the escarpment and recovered fresh andesitic clasts from debris flows along the northern segment of the ridge; they also recovered high-magnesium andesite lava blocks from the escarpment northwest of Chichijima. Three samples of andesite collected from the Bonin Ridge Escarpment range in age from 41.84 ± 0.14 to 43.88 ± 0.21 Ma (Ishizuka et al., 2006).

Boninites from the Bonin Islands are characterized by high MgO at given SiO2 concentrations, low high–field strength elements, low Sm/Zr, low REE, and a U-shaped REE pattern (Figure F3). These are “low-calcium boninites” (Crawford et al., 1989) and can be explained by low-pressure melting of depleted harzburgite that was strongly affected by slab flux. These boninites are isotopically characterized by high Δ7/4 Pb, high 87Sr/86Sr, and low 143Nd/144Nd relative to local MORB and FAB sources (Figure F5). In contrast to the FAB mantle source, which was not much affected by subduction-related fluids or melts, the boninite magma source manifests a major contribution from subducted pelagic sediment and oceanic crust. The boninites are also distinct from ~44 Ma lavas exposed on Hahajima Island and recovered by Shinkai 6500 diving on the Bonin Ridge Escarpment (Ishizuka et al., 2006). Younger boninite-series lavas from the Mikazukiyama Formation on Chichijima and the Bonin Ridge Escarpment are more similar to relatively enriched, less Ca depleted boninitic lavas from ODP Site 786 in the Izu-Bonin fore arc (Pearce et al., 1992) and Guam (Hickey-Vargas and Reagan, 1987), including having higher Sm/Zr at a given Zr content and higher REE and Ti concentrations compared to Chichijima boninite (cf. Taylor et al., 1994). These younger boninite-series lavas are isotopically distinct from the boninites (Figure F5) because they have a lower proportion of subducted versus mantle constituents.

Post-45 Ma, tholeiitic to calc-alkaline andesites from the Bonin Ridge and ~45 Ma rhyolites from Saipan (Reagan et al., 2008) exhibit strong characteristics of arc magmas: they are depleted in Nb and enriched in fluid-mobile elements such as Sr, Ba, U, and Pb. These characteristics indicate that, by 45 Ma, near-normal configurations of mantle flow and melting, as well as subduction-related fluid formation and metasomatism, were established for this part of the IBM arc. The Bonin Ridge Escarpment, Mikazukiyama Formation, and Hahajima andesites thus represent a transitional stage from the waning stages of fore-arc spreading (represented by FAB and perhaps boninites) and the stable, mature arc that developed in the late Eocene. These orthopyroxene-bearing, high-magnesium tholeiitic to calc-alkaline andesites erupted along the Bonin Ridge Escarpment as the arc magmatic axis localized and retreated from the trench. Post-45 Ma andesites (and basalts) do not show the influence of pelagic sediment melt from the slab (Figure F5). Instead, the mantle source seems to have only been affected by hydrous fluid derived mainly from subducted altered oceanic crust.

Overall, the geochemical and isotopic characteristics of the IBM arc along its entire length appear to have evolved in tandem with the formation of a new subduction zone and a new mantle flow regime:

- Initial decompression melting with little to no slab flux, producing MORB-like basalt and fore-arc spreading (51–52 Ma),

- Mixing of fluids or melts from subducted sediments and oceanic crust into an extremely depleted (harzburgitic) mantle to generate boninites (49–45 Ma), and

- Continued influx of hydrous fluid input into increasingly fertile lherzolitic mantle to generate tholeiitic and calc-alkaline magma (post-45 Ma), marking the time when a mature, stable arc magmatic system was finally established (Ishizuka et al., 2006, 2011).

Note however that although we have established a general volcanic stratigraphy for the IBM fore arc, it is a composite stratigraphy based on dredging, submersible grab sampling, and coring at widely spaced localities. There is no reference stratigraphic section to check this subduction initiation stratigraphy and, in particular, to identify the nature of the boundaries between the units and demonstrate that units have not been missed. Defining this stratigraphic section is the aim of this expedition.

Tectonic evolution

It has been generally accepted (Bloomer et al., 1995; Pearce et al., 1999; Stern, 2004; Hall et al., 2003) that the IBM subduction zone began as part of a hemispheric-scale foundering of old, dense lithosphere in the western Pacific (Figure F6). The beginning of large-scale lithospheric subsidence, not true subduction but its precursor, is constrained to predate the 51–52 Ma age of igneous basement of the IBM fore arc (Bloomer et al., 1995; Cosca et al., 1998; Ishizuka et al., 2006). The sequence of initial magmatic products is similar everywhere the fore arc has been sampled, implying a dramatic episode of asthenospheric upwelling and melting associated with magmatism and seafloor spreading over a zone that was perhaps hundreds of kilometers broad and thousands of kilometers long. It is clear from the extensive geochronology for IBM fore-arc rocks that this episode took place ~52 million years ago and was followed by a period of shallow hydrous melting through ~44–45 million years ago (Figure F2). Expedition 352 drilling sampled these parts of the tectonic history of the IBM arc.

Interestingly, these time-space trends in IBM fore-arc composition can be found in many ophiolite terranes. The world’s largest ophiolite, the Semail ophiolite of Oman/United Arab Emirates, has long been known to exhibit a stratigraphy of FAB-like tholeiites overlain by depleted arc tholeiites (e.g., Alabaster et al., 1982), and recent discoveries of boninites in the upper part of the sequence (Ishikawa et al., 2002) confirm the full trend from tholeiite to boninites. Other large, complete ophiolites with complex fore-arc-type stratigraphies involving tholeiites and boninites include the Troodos Massif of Cyprus, the Pindos Mountains in Greece, the Bay of Islands ophiolite in Newfoundland (Canada), and numerous others distributed through most of the world’s mountain belts (e.g., Pearce et al., 1984; Dilek and Flower, 2003). Many of these stratigraphies are economically significant, with associated volcanogenic massive deposits and/or podiform chromite mineralization.

The presence of boninites is in itself an important tectonic indicator, requiring a combination of shallow melting, high water content, and depleted mantle. Boninites are defined by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) to have >52 wt% silica, <0.5 wt% TiO2, and >8 wt% MgO and can usefully be distinguished from basalts on a diagram of Ti8 versus Si8, where Ti8 and Si8 refer to the oxide concentrations at 8 wt% MgO (Pearce and Robinson, 2010). On this projection (Figure F7), the earliest lavas are basalts (FAB) that plot in the MORB field. Later lavas (~48–44 Ma) plot as boninites before compositions eventually become basaltic again with eruptions at, for example, Hahajima. This appears to be a characteristic of subduction initiation but to properly interpret its tectonic significance we need the full lava stratigraphy to know whether the basalt–boninite transition is gradational or episodic or has both magma sources available simultaneously. Drill core would also enhance the opportunity to obtain glass samples that can be analyzed for volatile and fluid-mobile element concentrations.

After a brief period of spreading, lavas began to build atop the newly formed crust and retreat from the trench, at the same time changing composition, perhaps first from FAB to boninite and then from boninite to calc-alkaline and tholeiitic arc magmas. The timing and rate of the migration of the magmatic locus away from the trench remains uncertain, but it is clear that the locus of magmatism reached the location of the first magmatic arc on Guam and the edge of the Ogasawara escarpment within ~8 million years. This left vast tracts of infant arc crust “stranded” to form the IBM fore arc, which cooled and remained “frozen” in its primitive state. Understanding the formation of fore-arc crust is clearly critical for understanding the formation of subduction zones (and the magmatic responses), growth of arcs, evolution of continental crust, and origins of ophiolites.

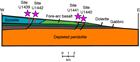

Structure and thickness of fore-arc crust

The most detailed trench-orthogonal published images of IBM fore-arc crustal structure near the Expedition 352 region come from a seismic refraction/reflection study by Kamimura et al. (2002) located some distance north of Sites U1439–U1442. While recognizing that the actual crustal structure for the drill sites might be slightly different than that shown, we infer from this study that the crust beneath the drill sites is 6–8 km thick—slightly thicker than normal oceanic crust. In detail, the crust beneath this part of the fore arc can be divided into five layers. The first layer (VP = 1.8–2.0 km/s) is mostly composed of thin sediment; this layer is very variable, and Sites U1439–U1442 were originally chosen to have at least 100 m of sediment in order to facilitate drilling and casing operations of the uppermost part of the holes. The second layer (VP = 2.6–3.3 km/s) is 1–2 km thick and probably consists of fractured volcanic rocks and dikes; this information contributed to our precruise estimate of 1.25 ± 0.25 km as the likely lava thickness that we needed to drill in order to reach the sheeted dikes.

Choice of drill sites

The Bonin fore arc was chosen because it had the advantage of being in the same region as Chichijima (Bonin Island), the type locality for the key boninite rock type. It is part of a complete ophiolite section that has been sampled by dredging and diving (Ishizuka et al., 2011) and has full site survey data (Kodaira et al., 2010, pers. comm., 2013).

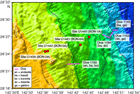

Two important hypotheses to be tested by drilling have been (1) that subduction initiation produces a consistent volcanic stratigraphy of (from oldest to youngest) FAB, transitional lavas, low-calcium boninites, enriched high-magnesium andesite and related rocks, and normal arc volcanic rocks (Reagan et al., 2010) and (2) that this sequence was originally stacked vertically before erosion and therefore represents an in situ analog for sections through many suprasubduction zone (SSZ) ophiolites. Sites U1439–U1442 (Figure F8) were chosen to maximize the likelihood of testing these hypothesis because the sheeted dike/FAB contact was approximately located during Shinkai 6500 diving in 2009 along the inner wall of the Bonin Trench, near a location where the drill could spud into a sediment pond and sample the lower part of the fore-arc volcanic succession.

Figure F9 summarizes the distribution of rocks sampled during three expeditions: YK04-05, the first manned submersible (Shinkai 6500) diving survey of the western escarpment of the Bonin Ridge (Ishizuka et al., 2006); R/V Hakuho-maru KH07-2, which dredged 19 stations along the length of Bonin Ridge; and YK09-06 in the proposed Site U1439–U1442 area (Ishizuka et al., 2011). They show that, in particular,

- Overall, there is an ophiolite-like sequence in the inner trench wall of lavas, dikes, gabbros, and peridotites;

- Of the lavas and dikes, MORB-like tholeiites occupy the deepest part of the trench-side slope of the ridge (i.e., the easternmost part of the ridge). These are chemically indistinguishable from FAB as defined by Reagan et al. (2010) from the Mariana fore arc;

- Boninites crop out to the west and upslope of the FAB/MORB outcrops; and

- Younger tholeiitic/calc-alkaline basalt to rhyolite crop out on the western Bonin Ridge and are especially well exposed on the western escarpment.

The 2009 diving survey using the Shinkai 6500 examined and better established the igneous fore-arc stratigraphy exposed on the trench-side slope of the Bonin Ridge (YK09-06 cruise: 24 May–10 June 2009; Ishizuka et al., 2011). The northernmost dive area near 28°25′N for this survey (Dives 1149, 1150, 1153, and 1154) was located near the drill sites (Figure F8).

The deepest dive (1149) sampled gabbro and basalt/dolerite and appears to have traversed the boundary between the two units. The lower slope traversed during Dive 1149 is composed of fractured gabbro, whereas pillow lavas were observed in the uppermost part of this dive at ~6000 m water depth. Dives 1153 and 1154 surveyed upslope of Dive 1149 between 6000 and 5200 m water depth. These two dives found outcrops of gabbro and dolerite, as well as fractured basalt lava cut by dikes. The contact between basalt and dolerite was thought to be ~5400 m based on these results, and Site U1440 was chosen to drill through this contact (Figure F10). The shallowest dive (1150; 4600 to 3700 m) recovered volcanic breccia and conglomerate with boninite. Thus, the boundary between boninite and basalt was estimated to lie at ~4000 m water depth. Site U1439 was chosen to drill through the transition zone from boninite to basalt. The resulting drilling has shown that this boundary might be geographically limited and lie to the east.

Scientific objectives

- Obtain a high-fidelity record of magmatic evolution during subduction initiation by coring volcanic rocks down to underlying intrusive rocks, including radiometric and biostratigraphic ages.

Recent advances in studying the IBM fore arc document important vertical compositional variations within the volcanic sections. We know that the IBM fore arc exposes rocks that formed after this subduction zone began at ~52 Ma (Stern and Bloomer, 1992; Ishizuka et al., 2011). Reagan et al. (2010) documented that the volcanic succession exposed in the inner trench wall of the southernmost Mariana fore arc comprises a volcanic succession that changes from MORB-like tholeiites at the base (FAB) through increasingly arc-like basalts to boninites near the top. They inferred that the 450–700 m sections cored at Sites 458 and 459 in the Mariana fore arc sampled the transition between the FAB and boninite successions. Similar successions are common in ophiolites, many of which are increasingly recognized as fossil fore arcs (Stern et al., 2012; see below). The significance of this simple succession has not hitherto been appreciated because of a lack of direct information on fore-arc volcanic stratigraphy, mainly because this was not a priority for dredging and diving. The results of Reagan et al. (2010) provide the first reconstruction of this stratigraphy, and this dredging and diving in the Bonin fore arc was undertaken to see whether a similar magmatic stratigraphy was present there. In the area, the results of Ishizuka et al. (2011) support the conclusions of Reagan et al. (2010). Drilling and coring of the volcanic succession at or near Sites U1439–U1442 will provide a crucial test of this hypothesis by providing a more continuous section. It is also important to further constrain the rates at which the fore-arc magmatic succession was emplaced. Evidence so far available indicates that this sequence takes 7–8 million years to form during subduction initiation, after which magmatic activity retreats ~200 km to the ultimate position of the arc magmatic front. Recovered cores should provide more material for U-Pb zircon, 40Ar/39Ar, and biostratigraphic age determinations.

- Use the results of Objective 1 to test the hypothesis that fore-arc basalt lies beneath boninites and to understand chemical gradients within these units and across their transitions.

We expect to find a thick section of FAB at the base of the Bonin fore-arc volcanic succession and a thinner sequence of arc-like and boninitic lavas at the top. To understand the significance of these vertical variations, we need to know how the transition from one magma type to the next takes place: is it a step-function, or is there a slow transition from one magma type to the next? If it is a transition, we need to know whether it is continuous, gradual, and progressive or whether it is accomplished by alternations of one magma type with another. Within the main FAB sequence, we need to know whether there is any evidence that the subduction component increases with stratigraphic height and thus time. A key related question is whether the boninites vary in any systematic way upsection, for example from high-calcium boninite at the base to low-calcium boninite near the top. The nature of these transitions and variations provide important constraints for how mantle and subducted sources and processes changed with time as subduction initiation progressed.

- Use drilling results to understand how mantle melting processes evolve during and after subduction initiation.

Assuming that we are able to accomplish Objectives 1 and 2, we will use the results to better understand how the mantle responds to subduction initiation. For example, a thick basal FAB succession indicates that adiabatic decompression is the most important process at the very beginning of subduction initiation in the IBM system, and an upper section of boninites indicates that flux melting was important just before the transition into normal arc magmatism. Whatever information is obtained from the cores will be used to construct geodynamic and petrologic models of this transition.

- Test the hypothesis that the fore-arc lithosphere created during subduction initiation is the birthplace of suprasubduction zone ophiolites.

Much has rightly been made of the highly successful efforts of IODP and its precursors in establishing the architecture and crustal accretion processes associated with mid-ocean ridges of varying spreading rates and linking these to ophiolites. As discussed earlier, however, it now appears that most ophiolites form when subduction begins, and that they are preserved as fore-arc crust until they are obducted. One testable hypothesis is that ophiolites that formed during subduction initiation can be recognized by a volcanic stratigraphy that varies from MORB-like at the base to arc-like or boninitic near the top, similar to the sequence that we expected to recover from the IBM fore arc. Most ophiolites are not well enough preserved or studied to infer volcanic chemostratigraphies, but some are and have volcanic stratigraphies that are similar to those of the IBM fore arc (e.g., Mesozoic ophiolites such as Pindos, Mirdita, Semail, and Troodos and Ordovician ophiolites of the northeast Appalachians and Norwegian Caledonides). Results from Bonin fore-arc drilling will allow us to prepare a more detailed volcanic chemostratigraphy expected for subduction initiation, which will in turn allow more detailed comparisons with these ophiolites.

Principal results

Site U1439 summary

Operations

After a 457 nmi transit from Yokohama, Japan, the vessel arrived at Site U1439 (proposed Site BON-2A; Figure F8). The vessel stabilized over the site at 0324 h (all times reported are ship local time, UTC + 9 h) on 6 August 2014. Because of the short initial period planned at this site, no seafloor-positioning beacon was deployed, and GPS was used for positioning the ship. A seafloor beacon was subsequently deployed once the vessel returned to Site U1439 on 26 August.

Site U1439 consists of three holes. Hole U1439A was cored using the advanced piston corer (APC)/extended core barrel (XCB) system to 199.4 meters below seafloor (mbsf) (Table T1). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used for Cores 352-U1439A-1H to 10H. Core orientation was performed using the FlexIT tool on Cores 2H through 9H. Temperature measurements were taken with the advanced piston corer temperature tool (APCT-3) on Cores 4H, 6H, 8H, and 10H. Basement was tagged with the XCB system for the purpose of identifying where in the volcanic stratigraphy this section belongs. Ten APC cores were taken over a 92.3 m interval and recovered 84.3 m (91%). Thirteen XCB cores were taken over a 107.1 m interval and recovered 86.4 m (81%). Overall recovery in Hole U1439A was 86%. The total time spent on Hole U1439A was 59.75 h.

Table T1. Expedition 352 operations summary. Download table in .csv format.

The vessel was offset 20 m east on 8 August, and Hole U1439B was drilled without coring to 42.2 mbsf for a jet-in test in advance of deploying casing beneath a reentry cone in Hole U1439C. After the completion of the jet-in test, the drill string was raised to 100 m above the seafloor, and at 2030 h on 8 August the vessel moved to Site U1440 using the dynamic positioning system.

After completion of operations at Site U1440, the vessel moved back to Site U1439 on 26 August. A reentry system was prepared, and 178.5 m of 10.75 inch casing was assembled and landed in the reentry cone in the moonpool. A drilling bottom-hole assembly (BHA), including a mud motor, underreamer, and bit, was picked up and installed. The casing with the reentry system attached was lowered to the bottom, drilled into the seafloor, and released on 27 August. Hole U1439C was cored with the rotary core barrel (RCB) system to 544.3 mbsf (Table T1). Coring was terminated on 8 September as a result of poor hole conditions. A total of 45 rotary cores were taken over a 362.3 m interval and recovered 107.8 m (30%). An additional 1.5 m of material was recovered during hole cleaning operations. The hole was logged to ~400 mbsf with the triple combination–Magnetic Susceptibility Sonde (triple combo-MSS) and Formation MicroScanner (FMS)-sonic tool strings. The total time spent in Hole U1439C was 382.75 h. The total time spent at Site U1439 was 447.75 h, or 18.66 days. The vessel moved to Site U1441 on 11 September.

Sedimentology

Sediment and sedimentary rocks were recovered from the seafloor to 176.47 mbsf in Hole U1439A, beneath which a thin interval of basic volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks was recovered within the igneous basement. The sediment represents the late Eocene–recent deep-sea sedimentary cover of the Izu-Bonin fore-arc basement. The underlying volcanogenic rocks are interpreted as the fore-arc basement. The sedimentary succession is divided into five lithologically distinct units (Figure F11). Lithologic Units I and II are each further divided into two subunits. The main criteria for the recognition of the lithologic units and subunits are a combination of primary lithology, grain size, color, and diagenesis. Within the overall succession, 44 ash or tuff layers were observed.

- Unit I (0–50.43 mbsf) is recognized mainly on the basis of a relatively high abundance of calcareous nannofossils compared to the sediment beneath. Unit I is divided into an upper, relatively nannofossil-poor subunit (0–5.54 mbsf) and a lower, relatively nannofossil-rich subunit (5.54–50.43 mbsf).

- Unit II (50.43–100.50 mbsf) is recognized on the basis of a downward change to silty mud and fine to coarse sand, in which the upper subunit (50.43–82.80) is relatively fine grained and the lower subunit (82.80–100.50 mbsf) relatively coarse grained.

- Unit III (100.50–110.93 mbsf) is easily recognizable because of a predominance of pale nannofossil ooze.

- Unit IV (110.93–129.76 mbsf) is marked by a distinct downward change to more clastic sediment dominated by clay, with minor silt, sand, and nannofossil-bearing sediment.

- Unit V (129.76–178.50 mbsf) is characterized by a diverse mixture of fine- to coarse-grained clastic sediment interbedded with fine-grained, nannofossil-rich sediment and sedimentary rock. The base of Unit V is defined as a thin (<3 cm) layer of dark gray to black, weakly consolidated manganese oxide–rich sediment.

Biostratigraphy

Calcareous nannofossils were present in 19 of 22 Hole U1439A core catcher samples and Sample 352-U1439A-20X-2, 0–2 cm. Preservation of calcareous nannofossils is variable, ranging from “good” in the most recent samples to “poor” in certain taxa and intervals. The oldest samples in the hole exhibit more diagenesis than younger samples. Reworking may be common throughout the section, making initial age constraints somewhat difficult. Close examination reveals somewhat continuous recovery from the Upper Pleistocene to the upper Eocene with a few gaps, especially in Miocene-aged sediment (Figure F11). The youngest age obtained was Late Pleistocene (Subzone CN14b; ~0.24–.424 Ma), whereas the oldest age was late Eocene/early Oligocene (Zones NP19/20 or NP21; ~34.76–35.92 Ma).

Fluid geochemistry

Twenty-one samples were collected in Hole U1439A for headspace hydrocarbon gas analysis as part of the standard shipboard safety monitoring procedure; one sample per core was collected from Cores 352-U1439A-1H through 23X, except for Cores 21X and 22X, in which no sediment was recovered. Thirteen whole-round samples were collected for interstitial water analyses in Hole U1439A, one sample per core from Cores 1H through 10H and one sample every three cores from Cores 13X through 19X. No headspace gas or interstitial water samples were collected from the basement rocks in Hole U1439C. All interstitial water samples were analyzed for salinity, alkalinity, pH, Cl–, Br–, SO42–, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and PO43–.

Methane concentrations range from 2.49 to 12.44 ppmv in Hole U1439A, with the highest methane concentration measured in Core 1H at 5.9 mbsf. This high value is attributed to decomposition of organic matter in the uppermost layers of the sedimentary column. No ethane or propane was detected in Hole U1439A samples. The major result of the interstitial water analyses from Hole U1439A is a broad correlation with the described lithologic units, with the exception of Mg2+ and Ca2+. The distribution of these elements in the sedimentary column is invariant of lithology and shows a downhole increase in Ca2+ to 40.5 mM and a decrease in Mg2+ to 39.2 mM. These variations can probably be attributed to metasomatism by interaction with fluids released from the basaltic basement.

Petrology

Igneous rocks were recovered in Holes U1439A and U1439C. Hole U1439A tagged basement during XCB coring (Cores 352-U1439A-20X through 23X; 3.7 m recovery), whereas Hole U1439C penetrated 362.3 m of igneous basement (Cores 352-U1439C-2R through 45R; 108.5 m recovery). The uppermost part of the section comprises heterolithic breccia, which represents seafloor colluvium. The lowermost part of the section is composed of mafic dikes or sills. The volcanic rocks in between are dominated by pillow lava with intercalations of massive sheet flows, igneous breccias especially hyaloclastites, and subaqueous pyroclastic flow deposits. This site is notable for the variety of boninites cored and for the intercalation of more and less differentiated boninites at several levels throughout the section. In one unit, these magmas appear to have erupted simultaneously, forming complex magma mingling textures. Phenocrysts are common in the basement boninitic rocks throughout Holes U1439A and U1439C. However, the variations in phase assemblages and abundances are not always diagnostic. As a result, chemical distinctions based on portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectrometry were also used to assess changes in rock composition and to track the occurrence of different magma series.

Ten igneous units were identified in the basement at Site U1439 (Figure F12). Unit boundaries represent an abrupt change in chemical characteristics, phenocrysts, and groundmass assemblages. Subunits typically represent changes in the eruptive nature of a unit (e.g., from hyaloclastite to pillow lava or massive lava), although minor changes in chemical composition occur at some subunit boundaries. Unit 10 is doleritic and was interpreted to represent sheeted shallow dikes or sills.

Fresh igneous rocks at Site U1439 are dominantly boninites characterized by phenocrysts of olivine and orthopyroxene and are typically set in a groundmass of pale glass and acicular to tabular pyroxene prisms. Acicular plagioclase is commonly present in the groundmasses of differentiated boninites. Phenocryst and groundmass assemblages document a range in boninite compositions:

- Orthopyroxene > olivine phenocrysts with an orthopyroxene-dominated groundmass (Units 1–4),

- Olivine + augite ± orthopyroxene phenocrysts with an augite ± plagioclase–bearing groundmass (Unit 5), and

- Olivine > orthopyroxene ± augite phenocrysts with augite ± orthopyroxene ± plagioclase in the groundmass (Units 6–9).

Based on using Niton handheld pXRF analyses, these units are also distinguished by their Ti/Zr ratios (see Preliminary scientific assessment): Unit 1 has very low Ti/Zr (<60), Unit 2 has significantly higher Ti/Zr (90–120), and Unit 3 has intermediate Ti/Zr (65–90).

Boninites in the first group are canonical boninites, to which we assigned the name “high-silica boninite,” whereas those in the second and third groups have lower silica concentrations and were assigned a shipboard classification of “basaltic boninite” and “low-silica boninite,” respectively (see discussion of nomenclature in Preliminary scientific assessment).The basaltic boninites in Hole U1439C are notable for their high magnetic susceptibilities. All boninites are notable for their low TiO2 contents and Ti/Zr compared with those of the fore-arc basalts of Site U1440.

Alteration in Hole U1439C basement units is highly variable. Fresh boninite glass is relatively common, but most samples have calcite, zeolite, and/or smectite clays partially or totally replacing groundmass, olivine and more rarely, orthopyroxene phenocrysts. Palagonite, clays, and more rarely, zeolites replace glass. Calcite and zeolite-filled veins and vesicles are common throughout the core, rarely associated with pyrite. Quartz is a rare component in some veins. The alteration generally becomes more intense with depth. Talc is present from Core 350-U1439C-22R to 26R. In fresh glass from Cores 28R to 33R, biogenic microtubes are common. Veins, principally of calcite, zeolite, and smectite, are abundant in Hole U1439C downhole to the boundary between boninite pillow lavas and dolerites.

Rock geochemistry

Whole-rock chemical analyses were performed on 48 igneous rocks and 22 sediment samples representative of the different lithologic units recovered from Site U1439. The 22 sediment samples were collected in Hole U1439A (1 per core) and analyzed for major and trace element concentrations and volatile contents. Hole U1439A sediments show a broad range of compositions, mainly marking the downhole changes in lithology from the carbonate-rich calcareous ooze (CaO > 50 wt%, Sr up to 2000 ppm, total C up to 11wt%, and Zr of ~30–40 ppm) to the clay- and volcaniclastic-rich silty muds (CaO < 2 wt%, Sr up to ~200 ppm, and Zr up to 150 ppm). The downhole transition to igneous basement is marked by a thin, muddy, manganese-rich layer (MnO = 2–5 wt%) and enrichments in Cu (>500 ppm), V (>200 ppm), and Zr (>150 ppm).

At the bottom of Hole U1439A, one orthopyroxene-phyric volcanic rock and one volcanic glass were sampled. In addition, 46 igneous rocks were selected by the Shipboard Science Party as representative of the different lithologies recovered from Hole U1439C. The rocks were grouped as olivine-pyroxene-phyric or plagioclase-bearing volcanic rocks. The 48 igneous rocks were analyzed for major and trace element concentrations by inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and for CO2 and H2O contents by gas chromatography for samples with loss on ignition (LOI) > 2 wt%. An aliquot of the powder used for ICP-AES analyses was subsequently used for XRF analyses, which were carried out with the pXRF. In addition, pXRF “chemostratigraphic” analyses were conducted on 350 archive-half pieces from Hole U1439C cores. The results of these chemical analyses, in conjunction with observations on core material and thin sections carried out by the petrology team, contributed to the lithologic division of the lavas into different units.

Site U1439 igneous rocks range from slightly to highly altered with LOI values from 2.5 to 16.2 wt%. LOI values primarily vary with H2O contents (0.5–8.8 wt%) and, thus, the amount and type of secondary hydrous minerals. However, several samples from the upper Units 1–8 also show high CO2 values (up to 6.4 wt%) together with higher Ca content, the result mostly of late carbonate addition. This shows that the primary compositions of several samples were modified significantly by alteration. For this reason, the alteration of igneous rocks of Hole U1439C was considered during interpretation of their primary geochemical signature.

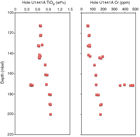

Igneous samples recovered from Hole U1439C are boninites with SiO2 concentrations ranging from 50.5 to 60.2 wt% at total alkali contents of 1.60–4.70 wt%. Olivine-pyroxene-bearing igneous rocks are characterized by high Cr concentrations (221–1562 ppm), high Mg# (cationic Mg/[Mg + Fe], with all Fe as Fe2+) of 64–80 and CaO/Al2O3 ratios of 0.49–0.93. The lowermost lavas and dolerites (Units 9 and 10) have lower Cr concentrations (51–750 ppm) and Mg# (59–76) than overlying units.

A characteristic feature of Site U1439 samples is the progressive decrease in TiO2 concentrations that characterize the transition from the lower Si igneous rocks sampled deep in Hole U1439C to the shallower, higher Si boninite samples. Another characteristic feature is the enrichments in highly incompatible and mobile elements (e.g., Ba) in igneous rocks sampled at Site U1439 compared to those from Site U1440. These enrichments are not correlated with indices of alteration and appear to be of magmatic origin.

Structural geology

Structures observed in Site U1439 cores originated from drilling-induced, sedimentary, igneous, and tectonic processes. Drilling-induced deformation in the sediment, including dragging-down, rotational shear, and postretrieval core dilation, prevented observation of sedimentary structures between ~92 and 155 mbsf. Sedimentary structures, such as bedding planes, stylolites, dewatering structures, and cross-bedding, point to an overall nearly horizontal bedding attitude. Igneous structures, although rarely observed, consist of local magmatic foliation marked by alignment of primary grains and a few centimeter-long enclaves in zones of magmatic mingling.

Tectonic structures, present mostly in igneous rocks, comprise tension fractures (veins), shear fractures, breccias, cataclasites, and fault zones. Veins are generally filled with (Mg-) calcite, zeolite, and clay. These veins typically dip steeply and do not correlate with the presence of faults. Vein thickness varies with depth and decreases from 350 to 500 mbsf. Three major fault zones occur at 348–401, 420–446, and 475–535 mbsf. The dominant sense of slip determined on slickensides is normal. Calcite microstructures in the deepest intervals include Type I and II twins, as well as subgrain boundaries, which suggests a relatively high differential stress.

Physical properties

Many of the physical property measurements display variability at similar depths, suggesting a few major boundaries. There is a distinct increase in natural gamma ray (NGR) values at 100–130 mbsf in lithologic Units III–IV. At 135–180 mbsf in Unit V, magnetic susceptibility and P-wave velocity increase. The reflectance parameters L*, a*, and b* decrease with depth from 0 to 130 mbsf in Units I–IV and display an abrupt increase in values at 128–130 mbsf at the boundary between Units IV and V. Bulk, dry, and grain densities show no systematic variation with depth. Porosity increases with depth from 0 to 130 mbsf in Units I–IV and decreases in Unit V.

Magnetic susceptibility distinctly increases and density distinctly decreases at 478–540 mbsf in igneous Units 9–10. NGR values decrease with depth from 180 to 390 mbsf in Units 1–6 and are low from 390 to 540 mbsf in Units 8–10, with some peaks correlated to magnetic susceptibility peaks. At 200–240 mbsf in Subunit 3a, density and P-wave velocity increase and porosity decreases. The reflectance parameters a* and b* have a small peak at 330 mbsf in Unit 3.

Paleomagnetism

Sediment cored in Hole U1439A is relatively strongly magnetic and has low coercivities, so it acquired a strong drill string overprint. This overprint was easily removed by alternating field demagnetization, revealing a Pliocene–Pleistocene magnetic stratigraphy in Cores 352-U1439A-1H through 10H (0–85 mbsf). Magnetic chrons downhole to the Gilbert Chron (~4.5 Ma) were clearly identified. The identification of older chrons downhole to Chron 3B is less certain. Cores 15X through 19X show clear magnetic polarity zones tentatively correlated with Chrons 8 through 13 (~25–34 Ma).

Igneous rock samples from Hole U1439C have mostly low inclinations with absolute values less than ~30° and an average of ~5°. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the Izu-Bonin arc formed near the paleoequator. Several zones of outlier paleoinclinations occur near observed fault zones. These anomalous values may be explained by remagnetization or tectonic rotation.

Downhole logging

A ~220 m interval of basement rocks in Hole U1439C was logged over a ~18 h period with two tool strings, the triple combo-MSS and FMS-sonic tool strings. Borehole conditions were relatively stable during logging operations, but weather conditions and sea state deteriorated as logging progressed. Spectral gamma ray, density, resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, sonic velocity, and microresistivity images were successfully acquired. Changes in the character and trend of these logs are used to define 7 logging units in this hole:

- Logging Unit 1 (~180–189 mbsf) is characterized by increasing values in total gamma ray, resistivity, density, and velocity, in combination with decreasing magnetic susceptibility downhole.

- Logging Unit 2 (~189–202 mbsf) shows decreases in density, resistivity, and magnetic susceptibility, whereas NGR is high relative to the units above and below.

- Logging Unit 3 (~202–213 mbsf) exhibits overall decreases in resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and gamma ray values with coincident discrete peaks in gamma ray and density.

- Logging Unit 4 (~213–246 mbsf) is characterized by high-frequency variations in both resistivity and magnetic susceptibility, in combination with anticorrelated profiles of density and total gamma ray values.

- Logging Unit 5 (~246–314 mbsf), the thickest of the logging units, is characterized by a wide range in magnetic susceptibility values, with a significant high in the uppermost 6 m of the unit.

- Logging Unit 6 (~314–365 mbsf) is delineated from Unit 5 by a major washed-out zone. The resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and velocity profiles through this interval are variable, which can, in part, be attributed to increased borehole rugosity.

- Logging Unit 7 (~365–402 mbsf, the bottom of the logged interval), has limited data available but is differentiated from the overlying unit by higher values of resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and total gamma ray values.

Overall, density, velocity, and resistivity increase with depth. Gamma ray and magnetic susceptibility values do not show such systematic changes with depth. The oriented microresistivity images show a wide range of features and textures in the walls of the borehole, including fracture networks, vesicles, and through-going planar features.

Although the logging unit boundaries do not correspond perfectly with the petrologic unit boundaries, there are clear relationships between the logging data and the physical properties and geochemistry of the core. Ongoing integration of the core and logging data sets will be essential in filling in some of the gaps in core recovery in the volcanic extrusive sequence of this hole.

Site U1440 summary

Operations

After an 8.2 nmi transit from Site U1439, the vessel arrived at Site U1440 (proposed Site BON-1A; Figure F8) and a positioning beacon was deployed at 0548 h on 9 August 2014. Site U1440 consists of two holes. Hole U1440A was cored with the APC to 103.5 mbsf and then cored with the XCB to a final depth of 106.1 mbsf (Table T1). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used with all APC cores. Cores 352-U1440A-1H through 6H were oriented using the FlexIT tool, which was removed with Core 7H as a result of the high heave conditions experienced by the vessel. APCT-3 temperature measurements were taken with Cores 4H, 6H, 8H, and 11H. Basement contact was recorded at ~101 mbsf. The APC coring system was deployed 12 times, with 103.5 m cored and 96.4 m recovered (93%). The XCB coring system was deployed twice, with 2.6 m cored and 0.2 m recovered (8%). The total time spent in Hole U1440A was 49.25 h.

A reentry system with a reentry cone and 99 m of 10.75 inch casing was drilled into the seafloor in Hole U1440B using a mud motor, underreamer, and drilling bit assembly. Coring with the RCB began at 102.3 mbsf in Hole U1440B and was terminated after bit failure at a final depth of 383.6 mbsf (Table T1). Basement contact was estimated at ~125 mbsf. The RCB coring system was deployed 36 times, with 281.3 m cored and 34.7 m recovered (12%). Following coring, two logging runs were made with the triple combo–Ultrasonic Borehole Imager (UBI) and FMS-sonic tool strings. As a result of deteriorating hole conditions, the triple combo-UBI tool string collected data downhole to 253 mbsf, and the FMS-sonic tool string collected data to ~243 mbsf. The total time spent in Hole U1440B was 364.75 h. The acoustic beacon was recovered at 0612 h on 26 August, and the vessel returned to Site U1439. The total time spent at Site U1440 was 414 h or 17.25 days.

Sedimentology

Sediment and sedimentary rocks were recovered from the seafloor to 103.5 mbsf in Hole U1440A, beneath which a thin interval of basic volcanic rocks was recovered. The sediment represents a section through the early Oligocene to recent deep-sea sedimentary cover of the IBM fore-arc basement. The underlying basaltic rocks recovered here are interpreted as representing the fore-arc basement. The sedimentary succession in Hole U1440A is divided into three lithologically distinct units (Figure F13). Unit I is further divided into three subunits, and Unit II is divided into two subunits. The main criteria used to define the lithologic units and subunits are a combination of primary lithology, grain size, color, and diagenesis.

- Unit I (0–32.98 mbsf) is recognized mainly on the basis of a relatively high abundance of poorly consolidated brown mud.

- Subunit IA (0–13.33 mbsf) is composed of mud with calcareous nannofossil and ash layers.

- Subunit IB (13.33–21.61 mbsf) is composed of mud with foraminifers and minor ash layers.

- Subunit IC comprises mud with diatoms, together with minor tuffaceous sandstone and ash layers (21.61–32.98 mbsf).

- Unit II (32.98–77.50 mbsf) is recognized on the basis of a downward increase in grain size to more clastic and volcanogenic sediment.

- Subunit IIA (32.98–58.50 mbsf) is relatively coarse grained and volcanogenic.

- Subunit IIB (58.50–77.50 mbsf) is even coarser grained and includes muddy volcanogenic breccia/conglomerate with gravel.

- Unit III (77.50–103.52 mbsf) exhibits a return to finer grained silty mud with subordinate volcanogenic gravel. The basalt beneath forms the top of the basement.

The proportions of the main sediment types recovered are

- Ash/tuff = 2.89 m or 2.9% of the total recovered sediments,

- Coarse-grained sediment (sand to conglomerate) = 16.5 m or 17.1%,

- Fine-grained mud, silt/mudstone, and siltstone = 75.51 m or 78.5%, and

- Nannofossil ooze = 1.24 m or 1.2%.

In addition, sediment was recovered in three cores immediately below the drilled interval in Hole U1440B (Cores 2R through 4R; 102.3 to ~115.3 mbsf). These cores correspond to Unit III in Hole U1440A.

Biostratigraphy

Calcareous nannofossils were recovered intermittently in Hole U1440A, where productive intervals are interspersed with barren intervals dominated by siliceous microfossils (especially radiolarians) and volcaniclastic material. There is a long barren interval from Sample 352-U1440A-6H-CC to 10H-CC. The youngest age obtained is Late Pleistocene (Subzone CN14a; ~0.44–1.02 Ma), and the oldest age obtained is early Oligocene (Zone NP23; ~29.62–32.02 Ma) (Figure F13). Three samples were examined from Hole U1440B. Samples 352-U1440B-2R-CC and 4R-1, 14–15 cm, contained calcareous nannofossils sufficient for age diagnostics, whereas Sample 3R-CC was barren. Preservation was moderate to poor in each sample, with many taxa showing strong dissolution and overgrowth. Both of the Hole U1440B samples have an early Oligocene age (Zones NP22 and NP21, respectively), with a range that is difficult to constrain better than ~32.02–34.44 Ma given the lack of reliable marker taxa for the equatorial Pacific. Absolute age determinations were more difficult to make at Site U1440 compared to Site U1439 as a result of increased dissolution and a number of barren intervals.

Fluid geochemistry

Twelve samples (1 per core) were collected in Hole U1440A for headspace hydrocarbon gas analysis as part of the standard shipboard safety monitoring procedure, and 12 whole-round samples were collected for interstitial water analyses (1 per core). No headspace gas or interstitial water samples were collected in Hole U1440B. All interstitial water samples were analyzed for salinity, alkalinity, pH, Cl–, Br–, SO42–, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and PO43–.

Only minor methane was detected in the headspace gas samples. The highest methane concentration (5.84 ppmv) was measured in Core 352-U1440A-1H at 1.5 mbsf and may be attributed to the decomposition of organic matter in the uppermost layers of the sediment.

The major result of the interstitial water analyses from Hole U1440A is the distinctive behavior of Mg2+ and Ca2+. Both elements have seawater concentrations at the top of the hole, but Ca2+ concentrations then decrease with depth to 41.2 mM at the bottom of the hole, whereas Mg2+ concentrations increase to 36.6 mM. These variations are independent of lithologic units and are attributed to pervasive fluid input from the underlying hydrothermally altered basaltic basement and alteration of volcanic ash in the sediment.

Petrology

Igneous rocks were recovered in both Holes U1440A and U1440B. Hole U1440A tagged basement during XCB coring with low recovery (Cores 352-U1440A-13X and 14X; 0.2 m recovered). Hole U1440B penetrated 268.3 m of igneous basement, again with low recovery (Cores 352-U1440B-4R through 36R; 33.9 m recovered). The basement/sediment contact is marked in both holes by a Mn-rich sediment layer or coating. The uppermost igneous unit in both holes comprises a mixture of volcanic rock fragments in a sediment matrix and likely represents talus or volcaniclastic breccia. This unit is ~35 cm thick and underlain by more than 175 m of volcanic rock, which transitions over ~70 m into dikes at 329.0 mbsf. The dikes are interpreted as part of a sheeted dike complex. The igneous basement is divided into 15 igneous units numbered in order of increasing depth (including the uppermost breccia) based largely on the physical nature of recovered lithologies, which were interpreted to be hyaloclastites, pillow lavas, sheet flows, and dikes (Figure F14).

Igneous rocks at Site U1440 are typically aphyric to sparsely phyric, plagioclase-pyroxene-magnetite phyric basalts with intergranular to intersertal textures. The coarser grained units in the dike complex and transition zone are dolerites with subophitic textures. All of the igneous rocks are petrographically similar to IBM FAB collected elsewhere and have chemical compositions consistent with this classification. They are distinct petrographically and chemically from the boninite-suite lavas, which are typically orthopyroxene and olivine phyric.

The degree of alteration of the igneous rocks at Site U1440 is low in the volcanic section where the secondary mineralogy is dominated by calcite, smectite-group clays, and zeolites including phillipsite. These minerals form abundant veins in Cores 352-U1440B-12R through 24R, some of which are associated with pyrite and native copper. Alteration becomes more intense in the transition zone and dike complex. Secondary minerals typically only replace the groundmass phases, leaving the silicate framework minerals (plagioclase and pyroxene) unaffected, except in the lower part of the dike complex where pyroxene and plagioclase may be partially replaced. Glass is commonly devitrified and, less commonly, replaced by palagonite, clays, and zeolite.

Rock geochemistry

Whole-rock ICP-AES chemical analyses were performed on 33 igneous rocks and 16 sediment samples representative of the different lithologic units recovered at Site U1440. Twelve sediment samples were collected from Hole U1440A (1 per core), and three samples were collected in the deepest part of the sediment sequence in Hole U1440B from 104.4 to 115.1 mbsf. Additionally, one sandstone piece was recovered within the igneous sequence in Section 352-U1440B-15R-1 (192.8 mbsf). One aphyric basalt sample was collected at the bottom of Hole U1440A, and 32 samples, mostly basaltic, were collected in Hole U1440B. The 16 sediment samples were analyzed for major and trace element concentrations and volatile contents. The 33 igneous rocks were analyzed for major and trace element concentrations. An aliquot of the powder used for ICP-AES analyses was subsequently used for pXRF analyses.

The sediment sampled at Site U1440 is dominantly silty mud, and its compositional variations reflect sedimentary unit changes. The range of compositions is more restricted than in the sediment in Hole U1439A. The sediment has, on average, low CaO contents (<2 wt%), high SiO2 contents (>55 wt%), and variable Cu concentrations (120–240 ppm). A few samples contain slightly higher carbonate contents with total C contents >0.9 wt%, CaO of 5–22 wt%, and lower Cu concentrations (70–90 ppm). Hole U1440B sediment has the same composition as that of lithologic Unit III sediment in Hole U1440A. Similarly, the sandstone recovered within igneous Unit 4 rocks overlaps in composition with lithologic Unit III sediment. This sandstone could represent an accidental fragment displaced by drilling or an accumulation of sand in an open fracture.

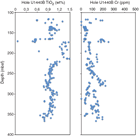

Site U1440 igneous rocks are mostly basalts with one andesite unit (igneous Unit 6). SiO2 ranges from 48 to 57 wt%, and total alkali (Na2O + K2O) contents vary from 2.1 to 3.2 wt%. These rocks are relatively depleted in incompatible trace elements (e.g., TiO2 = 0.6–1.4 wt%) and have highly variable Cr concentrations (15–380 ppm), indicating different degrees of differentiation. Downhole profiles of major element compositions exhibit a distinct increase in SiO2 concentrations and Mg# at ~260 mbsf. This depth marks the transition between igneous Units 7 and 8, which is interpreted as the boundary between the volcanic series and the lava/dike transition. The sampled igneous rocks have major element compositions similar to those of FAB collected by diving in the Bonin fore arc (cf. Ishizuka et al., 2011).

XRF chemostratigraphic analyses were conducted on archive-half pieces of cores and on thin section billets and powders. The results of these chemical analyses, in conjunction with observations on core material and thin sections carried out by the petrology team, contributed to the 15 unit lithologic division of the lavas and dikes and are discussed in Preliminary scientific assessment. Briefly, TiO2 and Zr concentrations in basalts generally decrease downhole from Unit 4. Although there is some cyclicity, Cr concentrations and Sr/Zr ratios increase over the same interval. Above Unit 4 the basalts have low Zr, TiO2, and Cr concentrations and relatively high Sr/Zr ratios. Unit 6 andesites are characterized by low TiO2 and Sr concentrations and the highest Zr concentrations of any lavas from Sites U1440 and U1441.

Structural geology

Bedding planes in the sediment are marked by dark pyroclastic beds and thin sandy layers and lay generally subhorizontal. Drilling-induced deformation of core features precluded meaningful structural measurements in the sediment between ~57 and 102 mbsf. In the igneous rocks, magmatic fabrics are rare and limited to a few centimeter-wide domains of grain alignment. Steep, metamorphic, chlorite-based foliation overprints primary fabrics at ~145–146, 281–291, and 358–369 mbsf. Tension veins filled with (Mg-) calcite, zeolite, chlorite, and clays are common at ~164–166, 202–264, and 319–369 mbsf. These veins typically form two sets at a high angle from each other with average dips of ~40° ± 10° and 80° ± 10°. The basalts and dolerites are overall free of plastic and cataclastic deformation features such as slickensides.

Physical properties

Changes in the trends of physical properties are encountered at similar depths, and these changes tend to be associated with different units. At ~10 mbsf in lithologic Unit I, there is a positive spike in P-wave velocity and NGR accompanied by a slight increase of gamma ray attenuation (GRA) density. This is an interval rich in tephra layers. At 35–40 mbsf in Unit II, P-wave velocity and GRA density increase sharply, whereas NGR decreases. Color reflectance parameters L*, a*, and b* decrease in the same interval. Physical properties show significant variability in Unit III. At 83–87 mbsf, magnetic susceptibility increases suddenly and color reflectance parameter L* decreases. At ~87–100 mbsf, P-wave velocity increases; magnetic susceptibility and NGR are variable but generally decrease with depth; color reflectance parameters decrease with depth; GRA, dry, and bulk density increase with depth; and porosity decreases with depth. At 100–102 mbsf, P-wave velocity, magnetic susceptibility, NGR and GRA, and dry and bulk density suddenly decrease accompanied by a sudden increase in porosity. Physical property parameters change in igneous Units 7 and 8. At ~230 mbsf in Unit 7, porosity decreases sharply, P-wave velocity increases, and bulk and dry density increase. At 270–280 mbsf in Unit 8, NGR decreases and magnetic susceptibility increases, with high values observed between 280 mbsf and the bottom of the hole.

Paleomagnetism

Remanent magnetization measurements reveal that sediment cored at Site U1440 is highly magnetic (~0.1–2 A/m natural remanent magnetization [NRM]), apparently as a result of input of volcaniclastic material from nearby sources. A normal Pliocene–Pleistocene magnetic stratigraphy has been established for the upper sedimentary section and includes the period from the upper Gilbert Chron (~4 Ma) to the Brunhes Chron at the surface. Paleomagnetic samples from the igneous basement section reveal a probable magnetic reversal sequence. The upper ~50 and lower ~120 m of the section have normal polarity, whereas the intervening ~70 m has reversed polarity. Until radiometric dates are available for the basement section, the pattern cannot be correlated with the geomagnetic polarity timescale.

Downhole logging

A ~130 m open hole interval of Hole U1440B was logged over a ~24 h period with two tool strings, the triple combo-UBI and the FMS-sonic. Although borehole conditions deteriorated while downhole logging was in progress, spectral gamma ray, density, resistivity, sonic velocity, and microresistivity images were successfully acquired.

Seven logging units are defined on the basis of the character and trend of the various logs. Logging Unit 1 (~99–116 mbsf) is characterized by relatively consistent resistivity and velocity with depth whereas the underlying Unit 2 (~116–122 mbsf) shows sharp increases in gamma ray, resistivity, and density downhole. Units 3 (~122–164 mbsf) and 5 (~170–211 mbsf) exhibit similarities in their log responses, steadily increasing in resistivity with depth and with no net change in gamma ray values. However, Unit 3 does show much greater variability in bulk density compared to the range of densities measured in Unit 5. Units 4 (~164–170 mbsf) and 6 (~211–222 mbsf) are relatively thin by comparison to Units 3 and 5 and are characterized by high resistivity, high velocity, and increasing density with depth. Unit 7 has limited data available but is differentiated from the overlying unit by a marked changed in the character of the resistivity log. Overall, there are downward increases in density, resistivity, and sonic velocity, whereas gamma ray values and porosity (as derived from resistivity) exhibit decreasing downhole trends. Microresistivity images overall echo the increasing resistivity with depth and also elucidate a range of textures and features through the logged interval.

Preliminary analysis of the data shows a reasonable agreement between the logging unit boundaries and the lithologic unit boundaries that were defined on the basis of core description and geochemical analyses. It is anticipated that the logging data, although only available for the lowermost sedimentary interval and upper volcanic extrusive section, will be useful in filling in some of the gaps in core recovery.

Site U1441 summary

Operations

The JOIDES Resolution completed the 6.2 nmi transit from Site U1439 in dynamic positioning mode while the drill string was being lowered to the seafloor. The vessel arrived at Site U1441 (proposed Site BON-6A) at 1512 h on 11 September 2014, and a seafloor positioning beacon was deployed.

Site U1441 consists of one hole. An RCB BHA was assembled with a C-4 bit. Hole U1440A was spudded at 2245 h on 11 September. The RCB coring system with nonmagnetic core barrels was deployed 22 times (Cores 352-U1441A-1R through 22R) and the hole was advanced to 205.7 mbsf (Table T1). Cores 11R and 12R had no recovery as a result of a plugged bit. Hole U1441A was terminated as a result of poor core recovery, the rubbly nature of the formation, and high risk of getting stuck. The RCB cores recovered 50.7 m over the 205.7 m cored interval (25%). The total time spent in Hole U1441A was 75.75 h. The seafloor positioning beacon was recovered at 0914 h on 14 September, and the vessel started the slow transit to Site U1442 while continuing to pull the drill string to the surface.

Sedimentology

Pelagic and volcaniclastic sediment was recovered from the seafloor to 83.00 mbsf, beneath which igneous rocks were recovered. The sedimentary succession is divided into five lithologically distinct units (Figure F15). Lithologic Unit I is further divided into two subunits. The volcanic rocks beneath are interpreted as the fore-arc basement. The main criterion for the recognition of the lithologic units and subunits is a combination of primary lithology, grain size, color, and diagenesis. Within the overall succession, 16 ash or tuff layers were observed. The bedding planes are generally oriented subhorizontally, with dip angles <10°.

- Unit I (0–15.02 mbsf) is divided into 2 subunits.

- Subunit IA (0–0.17 mbsf) is recognized by the occurrence of brownish mud with medium to coarse sand.

- Subunit IB (0.17–15.02 mbsf) is a relatively nannofossil-rich interval of silty calcareous ooze with nannofossils and sparse planktonic foraminifers.

- Unit II (15.02–24.50 mbsf) is recognized on the basis of a downward change to more clastic-rich sediment composed of muddy volcanic breccia/conglomerate and volcaniclastic sand layers.

- Unit III (24.50–58.64 mbsf) is characterized by a return to finer grained silty mud with relatively abundant radiolarians.

- Unit IV (58.64–70.38 mbsf) is distinguished by a distinct downward change to greener, relatively fine-grained sediment dominated by greenish gray silty clay.

- Unit V (70.38–83.00 mbsf) is a much coarser, mud-supported conglomerate with sandy and silty clay and also clay.

Biostratigraphy

Calcareous nannofossils were present in 3 of 10 core catcher samples. Samples 352-U1441A-1R-CC and 2R-CC are nannofossil oozes, whereas siliceous fossils dominate Sample 5R-CC. Preservation was moderate to good in each sample. Samples 1R-CC and 2R-CC yield an approximately Late Pleistocene age, whereas Sample 5R-CC yields an approximately late Miocene age (5.59–8.29 Ma). The widespread presence of radiolarians in the lower part of the sediments will help us improve the biostratigraphy postcruise.

Fluid geochemistry

Ten samples were collected from Hole U1441A for headspace hydrocarbon gas analysis as part of the standard shipboard safety monitoring procedure. Methane concentrations range from 1.08 to 1.29 ppmv, and neither ethane nor propane were detected.

Petrology

All of the igneous rocks at Site U1441 are FAB similar to those drilled at Site U1440. These basalts are also similar texturally and chemically to FAB recovered in diving expeditions in the region. They are dominated by modal plagioclase, clinopyroxene, and magnetite in the groundmass, and most are aphyric. Four units were identified based on hand specimen and thin section description and XRF data (Figure F16). Microphenocrysts of plagioclase are rare, but igneous Unit 3 contains 2%–3% clinopyroxene phenocrysts. Not surprisingly, Unit 3 is also the unit with the highest CaO content. Three chemical varieties of basalt were found. The upper basalts (Units 1 and 2) are depleted in TiO2 and Zr and have low Cr concentrations. The lowest basalts, which comprise Unit 4, are normal FAB very close in composition to those at Site U1440. In contrast, the Unit 3 basalts, which lie stratigraphically between these types, are among the most depleted basalts found along the IBM fore arc, with very low TiO2 and Zr concentrations and high Ti/Zr ratios. With the exception of Unit 3, TiO2, Zr, and Cr all show subtle increases steadily downhole.

Rock geochemistry

Seven igneous rocks from Cores 352-U1441A-10R to 22R were analyzed by ICP-AES for major and trace elements and by CHNS for CO2 and H2O contents. The igneous rocks recovered have LOIs of 2.0–4.6 wt%. They have higher H2O contents in the upper part of the basement (Unit 1) and relatively uniform H2O contents of 2.0–2.5 wt% in the lower units.

The igneous rocks recovered from Hole U1441A are all basalts, with SiO2 concentrations of 49–51 wt% and total alkali contents of 2–4 wt%. Overall, the major element composition of Site U1441 basalts is relatively homogeneous with MgO of 6.4–8.4 wt%, CaO of 10.7–11.6 wt%, and Fe2O3 of 10.8–12 wt%. Site U1441 basalts are very similar in composition to the IBM FAB previously recovered by drilling at Site U1440 and by diving. The single sample analyzed from Unit 3 has high Cr and CaO concentrations, high Mg#, and low concentrations of TiO2, Zr, and Y. This sample plots as a magnesian end-member composition on trace element variation diagrams but, despite its lower Ti contents, is both geochemically and petrographically distinct from Site U1439 boninites.

Alteration in Hole U1441A ranges from moderate to highly altered and tends to decrease downhole. The secondary assemblage consists of smectite group clays and zeolites with minor calcite (Figure F17). Clay minerals are dominant in the top half of the hole and downhole to Core 352-U1441A-16R. In the lower half of the hole, zeolite becomes the most abundant alteration mineral in the groundmass.

Structural geology

In the igneous units, viscous-plastic fabrics related to magmatic flow are rare and limited to millimeter- to centimeter-wide domains, defined primarily at the micro scale. These domains are relatively common in the lower parts of Hole U1441A (e.g., in Sections 352-U1441A-19R-1 and 22R-1). The magmatic foliation is mainly defined by the shape-preferred orientation of acicular feldspar crystals embedded within a glassy or microcrystalline matrix.

Extensional fractures without mineral fillings are subvertical and are observed at 85.15 and 180.45 mbsf. Subvertical to inclined, whitish, crystalline, millimeter-thick veins are abundant at 122.22–141.43 and 190.2–190.6 mbsf. In the lower interval the veins form steeply inclined conjugate sets. The vein-filling material consists of (Mg-) calcite and/or zeolite and/or chlorite.

Slickensides are abundant at 84.00–88.25 mbsf and dip steeply to subvertically. The general sense of shear is left-lateral strike-slip to oblique reverse, the latter including a left-lateral component as well. One subhorizontal slickenside shows a normal sense of shear. In the lowermost sections of Hole U1441A (interval 20R-1, 15–27 cm), a semiductile to brittle, low-angle shear zone was observed within a highly altered domain. The shear zone was recovered as a single piece with an oblong shape, without a preserved contact with the wall rock. Its position within the lithostratigraphic sequence cannot be defined exactly because of poor core recovery. The recovered basalt pieces below and above do not show any indication of comparable alteration or deformation. Within the shear zone, shear bands form subparallel sets, indicating a top-down sense of shear.

Physical properties

Many of the physical properties display similar downhole trends in the sedimentary section. P-wave velocities have peaks as high as 1580 m/s at 22–24 mbsf (lithologic Unit II) and 1540 m/s at 56–58 mbsf (Unit III). Magnetic susceptibility values also have peaks to 250–300 IU at the same depths. These peaks in P-wave velocities and magnetic susceptibility values correspond to tephra layers. GRA densities are 1.4–1.5 g/cm3, and NGR values are 10–20 counts/s from 0 to 69 mbsf. All of these parameters have a high peak at 70 mbsf at the bottom of Unit IV. Porosities are 65%–85% from 0 to 78 mbsf. Porosities are higher than 80% in Unit II and have the lowest value of 70% in Unit III.