Pecher, I.A., Barnes, P.M., LeVay, L.J., and the Expedition 372A Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 372A

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.372A.102.2019

Expedition 372A methods1

I.A. Pecher, P.M. Barnes, L.J. LeVay, S.M. Bourlange, M.M.Y. Brunet, S. Cardona, M.B. Clennell, A.E. Cook, M.P. Crundwell, B. Dugan, J. Elger, D. Gamboa, A. Georgiopoulou, A. Greve, S. Han, K.U. Heeschen, G. Hu, G.Y. Kim, H. Kitajima, H. Koge, X. Li, K.S. Machado, D.D. McNamara, G.F. Moore, J.J. Mountjoy, M.A. Nole, S. Owari, M. Paganoni, K.E. Petronotis, P.S. Rose, E.J. Screaton, U. Shankar, C.L. Shepherd, M.E. Torres, M.B. Underwood, X. Wang, A.D. Woodhouse, and H.-Y. Wu2

Keywords: International Ocean Discovery Program, IODP, JOIDES Resolution, Expedition 372, Site U1517, Hikurangi margin, Tuaheni Landslide Complex, Tuaheni Basin, New Zealand, gas hydrates, slope stability, fluid flow, mass transport deposits, logging while drilling

MS 372A-102: Published 5 May 2019

Introduction

This chapter documents the procedures and methods employed in the various shipboard laboratories of the R/V JOIDES Resolution during International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 372. This information applies only to shipboard work described in the Expedition reports section of the Expedition 372A Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program volume. Methods used by investigators for shore-based analyses of Expedition 372 data will be described in separate, individual publications. This introductory section provides an overview of operations, curatorial conventions, depth scale terminology, and general core handling and analyses.

Authorship of the site chapters

All shipboard scientists contributed to this volume. However, certain sections were written and edited by discipline-based groups of scientists as listed alphabetically below:

- Background and objectives: Barnes, Pecher

- Operations: Grigar, LeVay

- Lithostratigraphy: Brunet, Cardona, Georgiopoulou, Mountjoy, Underwood

- Biostratigraphy: Crundwell, Shepherd, Woodhouse

- Paleomagnetism: Greve, Li, Petronotis

- Geochemistry: Heeschen, Machado, Owari, Rose, Torres

- Physical properties: Bourlange, Hu, Kitajima, Nole, Screaton

- Downhole measurements: Dugan

- Logging while drilling: Clennell, Cook, Dugan, Elger, Gamboa, Han, Kim, Koge, McNamara, Moore, Paganoni, Shankar, Wang, Wu

- Core-log integration: Brunet, Cardona, Han, Nole, Paganoni, Screaton

- Log-seismic integration: Elger, Gamboa, Han, Moore

Site location

GPS coordinates from precruise site surveys were used to position the vessel at Site U1517. A Syquest Bathy 2010 CHIRP subbottom profiler was used to monitor the seafloor depth on the approach to the site to reconfirm the depth profile from precruise surveys. Once the vessel was positioned at the site, the thrusters were lowered and a positioning beacon was dropped to the seafloor. The dynamic positioning control of the vessel used navigational input from the GPS system and triangulation to the seafloor beacon weighted by the estimated positional accuracy. The final position for each hole at Site U1517 was the mean position calculated from the GPS data collected over a significant portion of the time the hole was occupied.

Coring and drilling operations

The advanced piston corer (APC) and half-length APC (HLAPC) systems were used during Expedition 372.

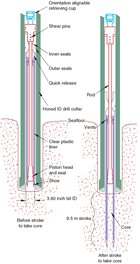

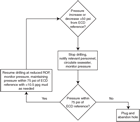

The APC and HLAPC systems cut soft-sediment cores with minimal coring disturbance relative to other IODP coring systems. After the APC core barrel is lowered through the drill pipe and lands near the bit, the drill pipe is pressured up until two shear pins that hold the inner barrel attached to the outer barrel fail (Figure F1). The inner barrel then advances into the formation and cuts the core. The driller can detect a successful cut, or “full stroke,” from the pressure gauge on the rig floor.

The depth limit of the APC system, often referred to as APC refusal, is indicated in two ways: (1) the piston consistently fails to achieve a complete stroke (as determined from the pump pressure reading) because the formation is too hard and limited core recovery is achieved, or (2) excessive force (>60,000 lb; ~267 kN) is required to pull the core barrel out of the formation. When a full stroke could not be achieved, one or more additional attempts are typically made, and each time the bit is advanced by the length of recovered core. This process results in a nominal recovery of ~100% based on the assumption that the barrel penetrated the formation by the length of core recovered. When a full or partial stroke is achieved but excessive force cannot retrieve the barrel, the core barrel is sometimes “drilled over,” meaning after the inner core barrel was successfully shot into the formation, the drill bit is advanced to total depth to free the APC barrel.

The standard APC system contains a 9.5 m long core barrel, and the HLAPC system uses a 4.7 m long core barrel. In most instances, the HLAPC system is deployed after the standard APC system reaches refusal. During use of the HLAPC system, the same criteria as for the full-length APC system are applied in terms of refusal. The HLAPC system allows significantly greater APC sampling depths to be attained than would otherwise be possible without this system.

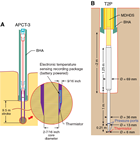

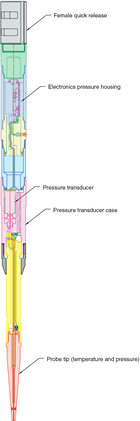

Nonmagnetic core barrels were used for all deployments of the APC and HLAPC systems. Orientation was applied to standard APC cores using the Icefield MI-5 core orientation tool and the FlexIT tool (see Downhole measurements). Formation temperature measurements were made to obtain temperature gradients and heat flow estimates using the advanced piston corer temperature tool (APCT-3). In situ formation pressure and temperature were measured using the temperature dual pressure probe (T2P) and the sediment temperature pressure tool (SETP) (see Downhole measurements).

The bottom-hole assembly (BHA) is the lowermost part of the drill string. A typical APC BHA consists of a drill bit (outside diameter [OD] = 11⁷⁄₁₆ inches [~29 cm]), a bit sub, a seal bore drill collar, a landing saver sub, a modified top sub, a modified head sub, a nonmagnetic drill collar (for APC), a number of 8¼ inch (~20.32 cm) drill collars, a tapered drill collar, six joints (two stands) of 5½ inch (~13.97 cm) drill pipe, and one crossover sub. A lockable flapper valve is used to collect downhole logs without dropping the bit when APC coring.

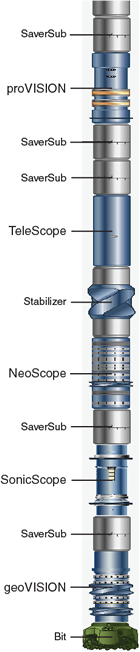

The logging-while-drilling (LWD)/measurement-while-drilling (MWD) BHA used during Expedition 372 consisted of an 8½ inch tungsten carbide insert tricone bit, an 8¼ inch near bit stabilizer/bit sub, various LWD/MWD tools, an 8¼ inch string stabilizer, a 6¾ inch (~17 cm) float sub, a crossover sub, twelve 6¾ inch drill collars, a 6½ inch (16.51 cm) drilling jar, three 6¾ inch drill collars, and a crossover to 5 inch (12.7 cm) drill pipe.

Drilling disturbance

Cores may be significantly disturbed as a result of the drilling process and may contain extraneous material as a result of the coring and core handling process. The uppermost 10–50 cm of each core must therefore be examined critically during description for potential “cave-in” and other disturbances (e.g., fluidization related to drill string heave in poor weather conditions). Common coring-induced deformation includes the concave-downward appearance of originally horizontal bedding. Piston action may result in fluidization (flow-in) at the bottom of APC cores. Retrieval from depth to the surface may result in elastic rebound. Gas that is in solution at depth may become free and drive core segments in the liner apart. When gas content is high, pressure must be relieved for safety reasons before the cores are cut into segments. This is accomplished by drilling holes into the liner, which forces some sediment, as well as gas, out of the liner. Drilling disturbances are described in Lithostratigraphy in the Site U1517 chapter (Barnes et al., 2019) and are graphically indicated on the visual core description (VCD) graphic reports (see Core descriptions).

Core handling and curatorial procedures

Special core handling procedures were implemented for gas hydrate identification and sampling. Cores recovered during Expedition 372 were extracted from the core barrel in plastic liners. These liners were carried from the rig floor to the core processing area on the catwalk outside the core laboratory. After wiping down the core liner, each core was immediately scanned with an infrared (IR) thermal imaging camera to identify gas hydrate layers, which appeared cold relative to the rest of the sediment core. Thermal images were collected and cataloged for each core in its entirety, regardless of whether it contained gas hydrates. If gas hydrate was observed with the IR camera, it was immediately marked on the core liner and sampled for interstitial water (IW) chemistry or post-expedition research. The gas hydrate samples collected for post-expedition research were cut out of the core in 5–14 cm long whole rounds, photographed, wrapped in aluminum foil, bagged, and placed in a dewar of liquid nitrogen. For some cores where gas expansion was happening quickly, holes were drilled into the core liner immediately to relieve the pressure. Once the core was sampled for gas hydrate, the cores were cut into sections. Sections are typically 1.5 m in length; however, because of whole-round sampling and gas expansion, these sections were often shorter. The exact section length was noted and later entered into the database as “created length” using the SampleMaster application. This length was used to calculate recovery. Whole-round samples were taken for IW chemistry at regular intervals. Headspace samples were taken from selected section ends (typically 2–4 per core) using a syringe for immediate hydrocarbon analysis as part of the shipboard safety and pollution prevention program. (See Geochemistry for more information on chemical sampling.) Core catcher samples were taken for biostratigraphic analysis during and after IODP Expedition 375. When catwalk sampling was complete, liner caps (blue = top; colorless = bottom; yellow = bottom where whole-round was removed) were glued onto liner sections with acetone, and sections were placed in core racks in the laboratory for analysis. Whole rounds for personal research were cut from the core sections after being processed through the physical properties whole-round loggers and after thermal conductivity measurements.

Numbering of sites, holes, cores, and samples followed standard IODP procedure. A full curatorial sample identifier consists of the following information: expedition, site, hole, core number, core type, section number, section half, and offset in centimeters measured from the top of a given section. For example, a sample identification of “372-U1517C-1H-2W, 10–12 cm,” represents a sample taken from the interval between 10 and 12 cm below the top of Section 2 (“W” indicates the working half of the section) of Core 1 (“H” designates that this core was taken with the APC system) of Hole C at Site U1517 during Expedition 372. The “U” preceding the hole number indicates that the hole was drilled by the JOIDES Resolution. Cores taken with the HLAPC system are designated as “F.”

Shipboard core analysis

Core sections were allowed to reach equilibrium with laboratory temperature (after ~4 h) prior to running through the Whole-Round Multisensor Logger (WRMSL) and Natural Gamma Radiation Logger (NGRL). Thermal conductivity was run on each whole-round core section. Based on the results of these physical properties measurements, whole-round samples for post-expedition research were cut from the sections. Each section was split lengthwise from bottom to top into working (“W”) and archive (“A”) halves. Investigators should note that older material might have been transported upward on the split face of each section during splitting. The working half of each section was sampled for shipboard analysis (physical properties, geochemistry, and bulk X-ray diffraction [XRD] mineralogy) and post-expedition research. The archive half of each section for each core was scanned on the Section Half Imaging Logger (SHIL) and measured for color reflectance and magnetic susceptibility on the Section Half Multisensor Logger (SHMSL). At the same time, the archive halves were described macroscopically, as well as microscopically by means of smear slides. Both halves of the core were then put into labeled plastic tubes that were sealed and transferred to cold storage space aboard the ship. The core sections remained aboard the ship through IODP Expeditions 374 and 375. During Expedition 375, the archive halves were run on the superconducting rock magnetometer (SRM).

All archive and working halves were transported at the end of Expedition 375 from the ship to the Gulf Coast Repository in College Station, Texas (USA), where they will be kept in permanent cold storage.

Sample depth calculations

The primary depth scale types are based on the measurement of the drill string length deployed beneath the rig floor (drilling depth below rig floor [DRF] and drilling depth below seafloor [DSF]) and the length of each core recovered (core depth below seafloor [CSF]). All depths are in meters. Depths of samples and measurements are calculated on the applicable depth scale by fixed protocol (e.g., CSF). The definition of these depth scale types and the distinction in nomenclature should keep the user aware that a nominal depth value on two different depth scale types usually does not refer to exactly the same stratigraphic interval in a hole.

Depths of cored intervals are measured from the drill floor based on the length of drill pipe deployed beneath the rig floor (DRF scale). The depth of the cored interval is referenced to the seafloor (DSF scale) by subtracting the seafloor depth at the time of the first hole from the DRF depth of the interval. In most cases, the seafloor depth is the length of pipe deployed minus the length of the mudline core recovered.

Standard depths of cores in meters below seafloor (CSF-A scale) are determined based on the assumptions that (1) the top depth of a recovered core corresponds to the top depth of its cored interval (DSF scale) and (2) the recovered material is a contiguous section even if core segments are separated by voids when recovered. Voids in the core are closed by pushing core segments together, if possible, during core handling. This convention is also applied if a core has incomplete recovery, in which case the true position of the core within the cored interval is unknown and should be considered a sample depth uncertainty (as much as the length of the core barrel used) when analyzing data associated with the core material. Standard depths of samples and associated measurements (CSF-A scale) are calculated by adding the offset of the sample or the measurement from the top of its section and the lengths of all higher sections in the core to the top depth of the cored interval.

A soft- to semisoft-sediment core from less than a few hundred meters below seafloor expands upon recovery (typically a few percent to as much as 15%), so the length of the recovered core exceeds that of the cored interval. Therefore, a stratigraphic interval may not have the same nominal depth on the DSF and CSF scales in the same hole. When core recovery (the ratio of recovered core to cored interval times 100%) is >100%, the CSF depth of a sample taken from the bottom of a core will be deeper than that of a sample from the top of the subsequent core (i.e., the data associated with the two core intervals overlap on the CSF-A scale). The core depth below seafloor, Method B (CSF-B), depth scale is a solution to the overlap problem. This method scales the recovered core length back into the interval cored, from >100% to exactly 100% recovery.

Wireline logging and in this instance LWD and MWD are measured on the LWD depth below seafloor (LSF) scale. LWD data are measured by time and are subsequently depth corrected.

It should be noted that all depths in this volume are given in meters below seafloor (mbsf) unless otherwise noted.

Lithostratigraphy

This section outlines the procedures used to document the composition, texture, and sedimentary structures of the sediment recovered during Expedition 372. The procedures include visual core description, digital color imaging, color spectrophotometry, smear slide analysis, and XRD analysis of bulk powders.

Core preparation for description

Archive halves were used for sedimentological and petrographic observations. Sections were dominated by unlithified sediment and split using a thin wire held in high tension. The split surface of the archive half was then scraped with a glass slide. Scraping parallel to bedding with a freshly cleaned tool prevents up- or downcore contamination. The archive half was then imaged by the SHIL and analyzed for color reflectance and magnetic susceptibility using the SHMSL (see Physical properties). We aimed to run the SHIL as soon as possible after core splitting to limit oxidation of the sediment surface obscuring sedimentary structures. The archive half was reimaged if required to improve the visibility of sedimentary structures and fabrics following treatment of the split-core surface. Following imaging, the archive halves of the sediment cores were macroscopically described for lithologic and sedimentary features aided by use of a 20× wide-field hand lens and binocular microscope.

Visual core descriptions

Visual inspection of sediment yielded information on lithologic variation, color, sedimentary structures, structural features, and drilling disturbance. Continuous or repeated bedded units were described as one interval rather than selecting a bed thickness cutoff for description. If an unusual bed occurred in an otherwise monotonous sequence, it was described separately. Smear slide analysis was used to identify sedimentary constituents, including microfossils. All of the descriptive data were entered into the DESClogik spreadsheet customized for Expedition 372 (see DESC_WKB in Supplementary material). All descriptions and sample locations were recorded using curated depths and documented on the VCDs (Figure F2). Graphic reports were assessed for quality control and consistency using the SHIL images and were adjusted and expanded where appropriate. Once core description was completed, Lithostratigraphic Units I–V were defined and included on the VCDs.

Graphic lithology

Lithologies in the core intervals are represented on the VCDs by graphic patterns in the Graphic lithology column (Figure F3). Other sedimentary features of the core, including sedimentary structures and sediment components, are represented by symbols. Bedding thickness for intervals described in packages are plotted as a rank. All grain size designations followed the conventional Wentworth (1922) scheme. Color was determined qualitatively for core intervals using Munsell color charts.

Lithologic features

The locations and types of stratification and sedimentary structures visible on the split-core surfaces were entered into DESClogik with their respective location and depth and shown in the Sedimentary structures column on the VCDs.

For Expedition 372, we used the following terminology (based on Stow, 2005) to describe the scale of stratification:

- Lamination = <1 cm thick.

- Very thin bed = 1–3 cm thick.

- Thin bed = >3–10 cm thick.

- Medium bed = >10–30 cm thick.

- Thick bed = >30–100 cm thick.

- Very thick bed = >100 cm thick.

We used these terms to define a scale for bedding thickness from 1 (lamination) to 5 (thick bed). We defined the following terms for sedimentary structures. Cross-bedding describes a bed that contains thin horizontal or inclined laminations with inclined internal foresets. Structureless beds were not specifically entered, but beds that are homogeneous in lithology and color and exhibit no bedding, cross-bedding, grading, bioturbation, or bed disturbance are described as massive in the core description. Sediment grading is described as ungraded, normally graded (fining upward), and inversely graded (coarsening upward). Contacts are either gradational, sharp, wavy, bioturbated, or irregular and are represented by symbols. A range of deformation structures were recognized and reported in a separate column on the VCDs. Bioturbation intensity was recorded with symbols as slight, moderate, and heavy. Any distinctive features not captured by symbols are listed in the section summary.

Drilling disturbance

Drilling-related sediment disturbance and intensity (slight, moderate, severe, and destroyed) are recorded in the Drilling disturbance column on the VCDs. Assessment of core disturbance by drilling and core processing was primarily based on the degree to which observed textures and fabrics depart from expected natural occurring features. In tectonically deformed sediment and landslide deposits, however, the distinction between natural and induced fabrics can be particularly ambiguous.

The type of drilling disturbance was described using the following terms:

- Flow-in (midcore or basal), coring/drilling slurry, or along-core gravel/sand contamination: soft-sediment stretching and/or compressional shearing structures are severe and are attributed to coring/drilling.

- Gas expansion: sediment is cracked horizontally, forcing apart parallel to bedding planes due to gas coming out of solution. Cores are typically pushed back together using a wooden plunger tool.

- Mingling and distortion of different beds: out-of-place material at the top of a core has fallen downhole onto the cored surface.

- Soupy: intervals are water saturated and have lost all aspects of original bedding.

- Upward-arching bed contacts: material retains its coherency, with material closest to the core liner bent downward. These contacts are most apparent when horizontal features are distorted.

- Void: open horizontal fractures most likely related to gas expansion are forcing core apart. These voids are recorded in comments only but indicated in core with labeled foam insert.

Smear slides

Smear slides were prepared according to IODP standard practice, and descriptions were recorded in data tables. These tables include information about the sample location, a description of where the smear slide was taken, the estimated percentages of texture (i.e., sand, silt, and clay), and the estimated percentages of composition (i.e., ash, siliciclastic, detrital carbonate, biogenic carbonate, and biogenic silica). Relative abundances of identified components such as mineral grains, microfossils, and biogenic fragments were assigned on a semiquantitative basis using the following abbreviations:

- D = dominant (>50% of the field of view).

- A = abundant (>20%–50% of the field of view).

- C = common (>5%–20% of the field of view).

- P = present (>1%–5% of the field of view).

- R = rare (0.1%–1% of the field of view).

- T = trace (<0.1% of the field of view).

X-ray diffraction

Samples for XRD analyses were selected from the working half at the same depth as sampling for solid-phase geochemistry and physical properties. Bulk powder samples were analyzed during Expedition 372, and the raw data files were processed on shore using MacDiff software. Diagnostic peaks for total clay minerals, quartz, feldspar, and calcite are listed in Table T1. Regression equations for computing relative mineral abundances are listed in Table T2. For additional details including sample preparation, instrument settings, and error analysis, see Wallace et al. (2019).

Biostratigraphy

The primary objectives of shipboard biostratigraphic analysis were to provide biostratigraphic ages and develop an integrated biostratigraphy for Site U1517. Preliminary age assignments were based on biostratigraphic analyses using calcareous nannofossils and planktonic foraminifers from 5 cm (176 cm3) core catcher samples. Additional 24 cm3 split-core samples were analyzed to locate the base of the Holocene more accurately. Benthic foraminifers were examined to provide data on paleowater depths and downslope reworking. In addition to the abundance and preservation of the major microfossil groups, the presence of other microfossil groups, including shell fragments, micromollusks, ostracods, otoliths, bryozoan fragments, echinoid spines and plates, fish teeth and remains, radiolarians, diatoms, and sponge spicules, was monitored.

The 2012 geologic timescale (GTS2012; Gradstein et al., 2012) was used during Expedition 372 in conjunction with the New Zealand geological timescale (Raine et al., 2015) to facilitate integration of Expedition 372 data with regional geological and seismic data (Figure F4).

Calcareous nannofossils

Calcareous nannofossil zones are based on the scheme of Martini (1971) (NN) with ages calibrated to GTS2012 (Gradstein et al., 2012) (Table T3).

Considerable variation in the size and morphological features of species in the genus Gephyrocapsa, which are commonly used as Pleistocene biostratigraphic markers, often causes problems in identification (e.g., Samtleben, 1980; Su, 1996; Bollmann, 1997). This study utilized size-defined morphological groups of this genus as event markers (Young, 1998; Maiorano and Marino, 2004; Lourens et al., 2004; Raffi et al., 2006), including small Gephyrocapsa spp. (<3.5 µm), medium Gephyrocapsa spp. (≥4 µm), and large Gephyrocapsa spp. (≥5.5 µm).

Species differentiation in and between “species” of Reticulofenestra that are used as Cenozoic biostratigraphic markers is often problematic (e.g., Backman, 1980; Su, 1996; Young, 1998). This study adopts the definition of Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus by Young (1998) as having a maximum coccolith length >7 µm, with smaller forms recorded as R. pseudoumbilicus 5–7 µm.

Taxonomic concepts for other species follow those of Perch-Nielsen (1985), Bown (1998, 2005), Dunkley Jones et al. (2009), and Shamrock and Watkins (2012), as compiled in the online Nannotax3 database (http://www.mikrotax.org/Nannotax3).

Methods

Calcareous nannofossil smear slides were prepared from core catcher samples using standard techniques. In some instances, strewn slides were prepared by mixing a small amount of sediment in a buffered solution (pH = ~8.5), which was left for 10–15 s to allow larger particles to settle before the suspended sediment was transferred with a pipette to a coverslip and placed on a warming plate to dry. Once dry, the coverslip was affixed to a glass microscope slide using Norland optical adhesive Number 61 and cured under ultraviolet light.

Slides were analyzed using an Olympus BX53 microscope at 400× to 1250× magnification in plane-transmitted light, cross-polarized light, and phase-contrast light.

Nannofossil preservation was noted as follows:

- G = good (little or no evidence of dissolution and/or overgrowth was observed, primary morphological features are slightly altered, and specimens were identifiable to the species level).

- M = moderate (specimens exhibit some dissolution and/or overgrowth, primary morphological features are somewhat altered, but most specimens were identifiable to the species level).

- P = poor (severe dissolution, fragmentation, and/or overgrowth was observed, primary morphological features have largely been destroyed, and most specimens could not be identified at the species and/or generic level).

Intermediate categories (e.g., G/M or M/P) were used in some cases to better describe the state of preservation of calcareous nannofossil assemblages.

Total nannofossil abundance in the sediment was visually estimated at 1000× magnification and reported using the following categories:

- D = dominant (>90% of sediment particles).

- A = abundant (>50%–90% of sediment particles).

- C = common (>10%–50% of sediment particles).

- F = few (1%–10% of sediment particles).

- R = rare (<1% of sediment particles).

- B = barren (no calcareous nannofossils).

The relative abundance of individual calcareous nannofossil species or taxa groups was estimated at 1000× magnification and noted as follows:

- D = dominant (>100 specimens per field of view).

- A = abundant (>10–100 specimens per field of view).

- C = common (>1–10 specimens per field of view).

- F = few (1 specimen per 1–10 fields of view).

- R = rare (<1 specimen per 10 fields of view).

- * = reworked (presence of species interpreted to be reworked).

- ? = questionable (questionable specimen of that taxon).

Foraminifers

Locally calibrated ages were used for all Neogene and Quaternary planktonic foraminifer datums based on Cooper (2004), Crundwell (2004), and Crundwell and Nelson (2007) (Table T4). Foraminifer criteria for the adopted marine paleoenvironmental classification, modified after Hayward et al. (1999), are shown in Figure F5.

The taxonomy of planktonic foraminifers follows a modified version of the phylogenetic classification of Kennett and Srinivasan (1983). Abbreviations for common genera are given in Table T5. Species concepts are primarily based on Hornibrook (1981, 1982), Hornibrook et al. (1989), Scott et al. (1990), Hornibrook and Jenkins (1994), Crundwell and Nelson (2007), and Crundwell (2015a, 2015b).

Qualifiers for taxa identified in this study are as follows:

- cf. = confer (compare with).

- sp. = unidentified species assigned to the genus.

- spp. = more than one unidentified species assigned to the genus.

- ? = identification uncertain.

Methods

Samples (5 cm whole rounds and 24 cm3 split-core samples) were prepared by manually breaking the core into small pieces and soaking them in hot water with a few drops of detergent. After ~5–10 min, samples were disaggregated and sieved to 125 µm to remove all mud and very fine sand. The washed residue retained on the sieve was then dried at 120°–150°C in an oven and divided with a microsplitter into equal aliquots for examination. As a precaution against cross-contamination, sieves were cleaned with jetted water and rinsed with methylene blue solution between successive samples.

The percentage of planktonic foraminifers relative to total foraminifers was determined quantitatively from random counts of 100 foraminifers in the 500–150 µm grain size fractions of the washed residues to determine oceanicity. Age and depth markers were then picked from successive 500–300, 300–212, and 212–150 µm grain size fractions and mounted onto 60-division faunal slides coated with gum tragacanth. As time allowed, other species and microfossils were also picked and mounted on the same slides. In most cases, the 500–212 µm grain size fraction was examined, and in samples where age diagnostic species were difficult to find, the 212–150 µm and 150–125 µm size fractions were also examined.

During the examination of microfossil samples, the abundance of foraminifers and other fossil groups in the 150–500 µm grain size fractions of washed samples was determined visually and categorized as follows:

- D = dominant (foraminifers compose >50% of the washed microfossil residue).

- A = abundant (foraminifers compose >20%–50% of the washed microfossil residue).

- C = common (foraminifers compose >5%–20% of the washed microfossil residue).

- F = few (foraminifers compose 1%–5% of the washed microfossil residue).

- R = rare (foraminifers compose <1% of the washed microfossil residue).

- X = present (present in sample; abundance undetermined).

In addition, the preservation of foraminifers was categorized as follows:

- VG = very good (specimens were mostly whole, very well preserved ornamentation and surface ultrastructure, and no visible modification of the test wall).

- G = good (specimens were often whole, ornamentation and surface ultrastructure were preserved but sometimes abraded or overgrown, and visible evidence of modification of the test wall).

- M = moderate (specimens were often etched or broken, the ornamentation and surface ultrastructure were modified, and the majority of specimens were identifiable to species level).

- P = poor (most specimens were crushed or broken, recrystallized, diagenetically overgrown, or infilled with crystalline calcite; most specimens were difficult to identify to species level).

Planktonic foraminifers

Planktonic foraminifer dating was used in conjunction with calcareous nannofossil dating to determine biostratigraphic ages. Planktonic foraminifers were also used to identify changes in marine climate. To achieve these goals, planktonic foraminifers that are useful for biostratigraphic dating and warm-water taxa denoting inflows of subtropical water were preferentially picked during the examination of samples. As time allowed, representatives of other planktonic species were also picked.

Benthic foraminifers

Benthic foraminifers were the primary paleontological tool used for estimating paleowater depths (Figure F5). In some instances, they were also used as secondary markers for biostratigraphic dating. Paleowater depths were estimated on the basis of the deepest calibrated depth marker contained in each sample using the markers given in Figure F5. Displaced shallow-water species (e.g., Hayward et al., 1999) that had been reworked downslope were also noted to identify redeposited sediment.

Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetic investigations on Site U1517 cores were conducted by shipboard scientists and technicians during Expedition 375. Because of time constraints, analyses were limited to natural remanent magnetization (NRM) measurement of archive halves prior to and following partial alternating field (AF) demagnetization. All measurements were conducted using a triaxial SRM (2G Enterprises, model 760R-4K) coupled with a 2G sample degaussing system that allows automated AF demagnetization by up to 100 mT. The system was designed for the continuous measurement of sections as long as 1.5 m and thus has a chamber with an 8.2 cm wide entrance. The response curves for each of the superconducting quantum interference device sensors have a total width of ~8 cm (H. Oda and C. Xuan, unpubl. data). Automated and continuous demagnetization is controlled using the in-house IMS-SRM v.9.2 software (SRM User Guide v.371 available on the JOIDES Resolution). Prior to leaving port, a profile of the background field across the measurement chamber was constructed using a fluxgate magnetometer (Applied Physics, type 520), showing that the field in the x-, y ‑, and z-directions does not exceed 0.008 nT. To minimize noise caused by dirt trapped in the measurement chamber, the sample tray was demagnetized twice per day using an AF of 40 mT followed by measurement of the tray only. This background field usually yields magnetic moments in the range of 3 × 10−9 A/m2 in the x- and y-directions and 4 × 10−12 A/m2 along the z-axis. Core sections were measured at a spacing of 2.5 cm. On each end of a section, an additional 10 cm was measured as a “header” and “trailer” to allow for deconvolution during future analysis. All data reported in the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) database are presented both in raw format and corrected for background field and magnetic drift of the sensors.

NRM measurements usually yield anomalous components of magnetization along core due to a viscous remanent magnetization acquired during the drilling process. All cores were thus subjected to stepwise AF demagnetization using 4–5 steps up to a peak field of 30 mT (Cores 372-U1517C-1H through 10F), 20 mT (Cores 11F–18H), or less, and NRM was measured following each demagnetization step. Calculated inclination, declination, and intensity were visually inspected using the IMS-SRM v.9.2 software and, where necessary, carefully analyzed using vector component diagrams (Zijderveld, 1967) to verify whether the remanence directions and/or magnetic polarities determined were of primary origin. Subsequently, variations in declination, inclination, and intensity records and interpreted polarity sequences with respect to depth below seafloor were displayed using MATLAB.

Coordinate convention and core reorientation

The magnetic data sets presented are displayed relative to the standard IODP coordinate system (Figure F6) with +z pointing downcore and +x pointing toward the double lines at the bottom of the working half and thus out of the archive half. The SRM coordinate system is inverted with respect to IODP coordinates (+zIODP = −zSRM). Conversion from SRM to IODP coordinates is thus required prior to data display, which occurs prior to data upload into the LIMS database. All paleomagnetic data (declination and inclination) discussed here refer to this convention.

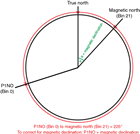

Cores 372-U1517C-1H and 2H were independently oriented using the FlexIT tool, and Cores 15H–18H were oriented using the Icefield MI-5 core orientation tool. The latter uses three orthogonally oriented fluxgate magnetometers to record the azimuthal orientation of the double lines (x-axis in IODP convention) with respect to magnetic north and thus provides an angular correction from core to geographic reference frameworks for each deployment (Arculus et al., 2015). Assuming that the borehole is vertical, declination data sets can be related to a geographic reference frame using

- DTrue = corrected and desired declination value,

- Dobserved = data measured and described in IODP coordinate system,

- AzFlexIT = angle between magnetic north and the double lines on the core liner, and

- Dlocal = local compass declination.

Experience from previous expeditions suggests that the accuracy of reorientation falls between 20° and 30° (McNeill et al., 2017). The local declination of the 12th generation International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF) (Thébault et al., 2015) at the drill site in December 2017 was 21.23° (calculated using https://www.ngdc.noaa. gov/geomag-web).

Geochemistry

The Expedition 372 coring program was designed to establish the mechanisms responsible for the creeping behavior of the Tuaheni Landslide Complex (TLC). The three main objectives of the geochemistry program for Site U1517 were to (1) determine gas hydrate presence and its potential link to the style of deformation observed at the TLC, (2) establish distribution and cycling of methane, and (3) provide information on transient events that may result from recent mass transport deposition, gas hydrate dynamics, fluid migration, and changes in upward methane flux. In addition, the geochemical data will be useful for evaluating biogeochemical processes, particularly element cycling in response to ash alteration processes in methanic sediment.

Pore fluid sampling protocol

Samples were collected on the catwalk at a frequency of four samples per core in the upper 15.2 m (Cores 372-U1517C-1H through 2H) and two samples per core from 15.2 to 112.4 mbsf (Cores 3F–19F). Deeper than 112.4 mbsf, care was taken to select samples where the IR camera scans suggested the potential for gas hydrate occurrence, as well as in sections away from IR anomalies (background samples), resulting in a sampling frequency of as many as six samples per HLAPC core (see Geochemistry in the Site U1517 chapter [Barnes et al., 2019]).

For headspace analyses of gas concentrations, three sediment plugs of 3 mL each were routinely collected; one plug was used for standard hydrocarbon concentration monitoring on board, and the other two were used for stable isotope measurements at onshore laboratories. Headspace samples were collected adjacent to most IW samples when they were taken, resulting in 1–5 samples per core. In cases where not enough core was recovered for IW sampling or the presence of sand layers prevented collection of IW samples, headspace samples were taken at a minimum resolution of one sample per half core for safety monitoring purposes. When gas voids were present, they were sampled at a frequency of 1–4 samples per HLAPC core.

Pore fluid collection

Whole-round (WR) core samples were cut on the catwalk, capped, and taken to the laboratory for processing. During high-resolution sampling, when there were too many IW samples to process immediately, capped WR core samples were stored under a nitrogen atmosphere at 4°C until they were squeezed, which occurred no later than 30 h after core retrieval.

After extrusion from the core liner, the surface of each WR IW sample was carefully scraped with a spatula to remove potential contamination from seawater and from sediment smearing in the borehole. The remaining sediment (~150–300 cm3) was placed in a titanium squeezer modified after the stainless steel squeezer of Manheim and Sayles (1974). Samples were squeezed at gauge forces of as much as 30,000 lb. The squeezed pore fluids were filtered through a prewashed Whatman Number 1 filter placed in the squeezers above a titanium screen. The squeezed pore fluids were collected in precleaned, plastic syringes attached to the squeezing assembly and subsequently filtered through a 0.2 µm Gelman polysulfone disposable filter.

Sample allocation was determined based on the pore fluid volume recovered and on analytical priorities based on the expedition objectives. The shipboard analytical protocols are summarized in the following section.

Gas hydrate samples

For some of the intervals in which the IR camera records suggest the potential for gas hydrate occurrence, whole rounds were collected at the catwalk and immediately immersed in a Dewar filled with liquid nitrogen for storage and shipping to onshore laboratories.

Shipboard pore fluid analyses

Pore fluid samples were analyzed on board following the protocols in Gieskes et al. (1991) and the online IODP user manuals.

Salinity, alkalinity, and pH

Salinity, alkalinity, and pH were measured immediately after squeezing. Salinity was measured using a Fisher temperature-compensated handheld refractometer, pH was measured with a combination glass electrode, and alkalinity was determined by Gran titration with an autotitrator (Metrohm 794 basic Titrino) using 0.1 M HCl at 20°C. International Association for the Physical Sciences of the Oceans (IAPSO) standard seawater was analyzed at the beginning and end of each set of samples and after approximately every 10 samples.

Chloride, sulfate, and bromide

High-precision chloride concentrations were acquired using a Metrohm 785 DMP autotitrator and silver nitrate (AgNO3) solutions that were calibrated against repeated titrations of an IAPSO standard. A 0.1 mL aliquot of sample was diluted with 10 mL of 90 ± 2 mM HNO3 and titrated with 0. 014 M AgNO3. Repeated analyses of an IAPSO standard yielded a precision better than 0.5%.

Sulfate (SO42−), chloride (Cl−), and bromide (Br−) concentrations were analyzed using 100 µL aliquots diluted 1:100 with deionized water (18 MΩ·cm). Measurements were conducted using a Metrohm 850 Professional ion chromatograph (IC) with eluent solutions of 3.2 mM Na2CO3 and 1.0 mM NaHCO3. Concentrations were determined using peak areas. The analytical protocol was to run a standard after five samples for six cycles, after which three extra standards were analyzed. The standards used were based on IAPSO dilutions of 50×, 80×, 150×, 250×, 500×, 750×, 1000×, 1200×, 1500×, and 2000×. Sample replicates (N = 5) were analyzed during each run for reproducibility. Reproducibility was also checked based on the interspersed standard samples run throughout the expedition. Analytical precision was better than 2% for these anions. Sulfate concentrations below ~0.85 mM are below the detection limit with the calibration curve used. Chloride analyses by both titration and IC agree within 2%; for Expedition 372 we report both values but plot only the titration data.

Ammonium, phosphate, and silica

Ammonium, phosphate, and silica concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry using an Agilent Technologies Cary Series 100 UV-Vis spectrophotometer with a sipper sample introduction system following the protocol in Gieskes et al. (1991). Phosphate was measured using the ammonium molybdate method described in Gieskes et al. (1991) with appropriate dilutions. Orthophosphate reacts with Mo(VI) and Sb(III) in an acidic solution to form an antimony-phosphomolybdate complex. Ascorbic acid reduces this complex to form a blue color, and absorbance is measured spectrophotometrically at 885 nm.

The ammonium method is based on diazotization of phenol and subsequent oxidation of the diazo compound by Clorox to yield a blue color measured spectrophotometrically at 640 nm. Samples were diluted prior to color development so that the highest concentration was <1000 µM.

Silica was also measured spectrophotometrically using the method based on the production of a yellow silicomolybdate complex. The complex is reduced by ascorbic acid to form molybdenum blue and measured at 812 nm.

Major and minor elements by ICP-AES

Dissolved major (Na, K, Ca, SO4, and Mg) and minor (Li, Sr, B, Si, Mn, Fe, and Ba) elements were determined by an Agilent 5110 inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES) with an SPS4 autosampler. This instrument was newly installed at the start of IODP Expedition 371 (July 2017), and new analytical procedures were developed during IODP Expeditions 371 and 369.

For shipboard ICP-AES analyses of IW samples collected during Expedition 372, we adopted a procedure that incorporates aspects of the methods previously developed for this instrument with the goal of establishing a procedure that (1) takes advantage of the new capabilities of the Agilent 5110 to measure major and minor ions in the same run using both the radial and axial configurations, (2) is simple enough for routine use, and (3) generates good quality data. Each acidified IW sample was diluted 1:10 using 2% HNO3 and spiked with 100 µL of a 10 ppm Y solution as an internal standard. For calibration, serial dilutions of IAPSO standard seawater (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 110%, and 200%) were prepared to cover IW concentrations smaller than or equal to normal seawater. Additional calibration solutions for major and minor element concentrations exceeding seawater (Ca, B, Ba, Fe, Li, Mn, P, Si, and Sr) were prepared with 3.5% NaCl as a matrix. Calibration solutions were made up from certified stock solutions for minor elements (B, Ba, Fe, Li, Mn, P, Si, and Sr) and spiked in the same way as the IW samples.

During each ICP-AES run, a complete set of all in-house and IAPSO dilutions were analyzed at the beginning and end of each batch. Furthermore, solutions of 100% concentration in-house and IAPSO standards were run every 8–10 samples to monitor instrumental drift. The elemental concentrations reported for each sample were average values from three replicate integrations from each sample measured consecutively via continuous flow, as set by instrumental parameters. The standard error in the average was also calculated by the instrument software.

Following each ICP run, the measured concentrations were recalculated after setting background correction parameters and adjusting peak centers using software that accompanies the ICP. Precision was determined by the instrument from triplicate runs of each sample.

Major elements by ion chromatography

The shipboard IC (Metrohm 850 Professional IC) also yields major cation (Ca, Mg, Na, and K) concentration data. Samples analyzed on the IC were diluted 100 times with Milli-Q water. The eluent solutions used for cation measurements were 3.2 mM Na2CO3 and 1.7 mM pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDCA), supplied by Metrohm (CAS#499-83-2). Concentrations were determined using peak areas. The analytical protocol was to run a standard after five samples for six cycles, after which three extra standards were analyzed. The standards used were based on IAPSO dilutions of 50×, 80×, 150×, 250×, 500×, 750×, 1000×, 1200×, 1500×, and 2000×. Sample replicates (N = 5) were analyzed during each run for reproducibility. Reproducibility was also checked based on the interspersed standard samples run throughout the expedition. Analytical precision was 0.3% for Na and K, 0.6% for Mg, and 1.0% for Ca.

Preference for multiple data sets

Often, more than one data set was produced for the concentration of a dissolved species. For example, Ca, Mg, K, Na, Sr, Si, B, Ba, Fe, and Mn were measured using two or more wavelengths by ICP-AES, and the adoption of each wavelength was based on data quality details. In addition, Ca, Mg, K, and Na were measured by IC, and Si was measured by spectrophotometry. Cl− concentrations were analyzed by titration and IC. The data plotted reflect the chosen method of analyses, which is listed in Table T6. This table also includes the chosen ICP-AES wavelength and the estimated precision of each analysis.

Fluid organic geochemistry

Routine analysis of hydrocarbon gases in sediment cores is a part of the standard IODP shipboard monitoring program to ensure that the sediments being drilled do not contain greater than the expected amounts of higher hydrocarbons (Pimmel and Claypool, 2001). The most common method of hydrocarbon monitoring used during IODP expeditions is the analysis of gas samples obtained from sediment samples (headspace analysis) following the procedures described by Kvenvolden and McDonald (1986).

For headspace analyses, three 3 cm3 bulk sediment samples were collected from the freshly exposed top end of a core section and next to the IW sample immediately after core retrieval using a 3 mL plastic syringe with the top cut off. The sediment plug designated for shipboard analysis was sealed with an aluminum crimp cap and silicon septa. The vial was then heated to 70°C for ~30 min to evolve hydrocarbon gases from the sediment plug. A 5 cm3 volume of headspace gas was extracted from the sealed sample vial using a standard gas-tight syringe and was analyzed by gas chromatography.

The remaining two sediment plugs were collected to measure the stable carbon and hydrogen isotopic composition of hydrocarbons at onshore laboratories. The sampling method is the same as that used for the safety analysis, except that the sediment plug is extruded into a 20 cm3 headspace glass vial filled with 10 cm3 of a 1 M potassium chloride (KCl) solution and sealed with an aluminum crimp cap and Teflon/butyl septum. The vial was then vigorously shaken to help dissociate the sediment. Potassium chloride is toxic and was used to stop all microbial activity in the sediment. The vials were flushed with N2 and capped within 1 h prior to sampling to remove air from the headspace and ensure the sample was preserved anaerobically.

When gas pockets occurred in the expanding cores, the free gas was drawn from the sediment void using a syringe attached to a hollow stainless steel tool used to puncture the core liner. The gas was then injected into a presealed 20 mL vial filled with 2 M NaCl solution. The gas injected into the vial replaced the brine. This way, contact with air was minimized. The void gases were initially collected for onboard measurements of the gas composition and stable isotope measurements of carbon and hydrogen of the hydrocarbons on shore. Because of difficulties with the calibration of the natural gas analyzer (NGA) gas chromatographic setup, all measurements will be done on shore.

The composition of headspace samples was measured using one of the two shipboard gas chromatographs (GCs), designated as GC3 and NGA. During Expedition 372, the GC3 system was the only one used. Calibrations of the NGA for higher hydrocarbons and particularly nonhydrocarbon gases turned out to be insufficient to allow for onboard measurements.

The GC3 is an Agilent 7890 gas chromatograph with a flame ionization detector (FID) used to determine concentrations of light hydrocarbon gases C1–C3 (alkanes and alkenes). It is equipped with a 25 µL sample loop, a 10 port VALCO valve, an 80/100 mesh 8 ft HayeSep R packed column (2.0 mm inside diameter [ID] × ⅛ inch OD), and an FID set at 250°C. The GC3 oven temperature was programmed to hold for 8.25 min at 80°C, ramp at 40°C/min to 150°C, hold for 5 min, and return to 100°C postrun for a total of 15 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas. Precision and accuracy are ±2% for concentrations as high as 10,000 ppm and ±1% for higher values.

Chromatographic response is calibrated using nine preanalyzed standards with methane concentrations ranging from 15 to 900,000 parts per million by volume (ppmv). The standards with high methane concentrations are likely to contain small amounts of ethane not used for calibration. The gas concentrations for the required safety analyses are expressed as component parts per million by volume relative to the analyzed gas. Data were collected using the Hewlett Packard 3365 Chemstation data processing program.

Sediment geochemistry

For the shipboard sediment geochemistry analyses, 5 cm3 of sediment was freeze-dried for ~24 h, crushed to a fine powder using an agate pestle and mortar, and sampled to analyze inorganic carbon, total carbon (TC), and total nitrogen (TN).

The TC and TN of sediment samples were determined with a ThermoElectron Corporation FlashEA 1112 carbon-hydrogen-nitrogen-sulfur (CHNS) elemental analyzer equipped with a ThermoElectron CHNS/nitrogen-carbon-sulfur (NCS) packed column and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Approximately 10–15 mg of freeze-dried, ground sediment was weighed and sealed in a tin capsule, and the sample was combusted at 900°C in a stream of oxygen. The reaction gases were passed through a reduction chamber to reduce nitrogen oxides to nitrogen and were then separated by gas chromatography before detection by TCD. All measurements were calibrated to a standard sediment reference material (National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST] 2704 Buffalo River Sediment) for carbon and nitrogen detection, which was run every six samples as a verification. The detection limit was 0.001% for TN (instrument limit) and 0.002% for TC (procedural blank; measured as an empty tin cup). Sample replicates (N = 10 for each of five samples) yielded precisions of <10% for TN and <7% for TC.

Total inorganic carbon (TIC) concentrations were determined using a UIC 5011 CO2 coulometer. Between 10 and 15 mg of freeze-dried, ground sediment was weighed and reacted with 2 M HCl. The liberated CO2 was titrated, and the end point was determined by a photodetector. Calcium carbonate content expressed as weight percent was calculated from the TIC content assuming that all evolved CO2 was derived from dissolution of CaCO3:

No correction was made for the presence of other carbonate minerals. Accuracy during individual batches of analyses was determined by running a carbonate standard (100 wt% CaCO3) every 10 samples. Typical precision, assessed using replicate analyses of carbonate samples (N = 10 for each of 5 samples), was 2%. The detection limit for CaCO3, defined here as 3× the standard deviation of the blank (2 M HCl), was 0.1%. Total organic carbon (TOC) content was calculated as the difference between TC (measured on the elemental analyzer) and inorganic carbon (measured by coulometry):

Physical properties

Physical properties measurements provide fundamental information required to characterize lithostratigraphic units and allow for correlation of cored materials with logging data. A comprehensive discussion of methodologies and calculations used in the JOIDES Resolution physical properties laboratory is presented in Blum (1997).

After sectioning (see Core handling and curatorial procedures), core sections were moved into the laboratory to equilibrate to room temperature for ~4 h. After thermally equilibrating, core sections longer than 30 cm were run through the WRMSL for measurement of gamma ray attenuation (GRA) bulk density, magnetic susceptibility, and compressional wave (P-wave) velocity (P-wave logger [PWL]). Sections longer than 50 cm were measured with the spectral NGRL.

Thermal conductivity measurements were carried out on two whole-round core sections per full core (APC) or one section per half core (HLAPC) using the needle probe technique. After cores were split into archive and working halves, the archive half was passed through the SHIL for digital image scanning on the cut surface and the SHMSL for measurement of point magnetic susceptibility (MSP) and color spectrophotometry (see also Lithostratigraphy).

Discrete samples for moisture and density (MAD) measurements were taken from the working half at a frequency of approximately one per section. In sections where whole-round core samples were removed for interstitial water or other testing, MAD samples were located close to these samples to help characterize the tested interval. MAD measurements yielded wet bulk density, dry bulk density, grain density, water content, void ratio, and porosity. P-wave velocity was measured on the working half, and strength was measured using the automated vane shear (AVS) apparatus and penetrometers. P-wave velocity and strength measurements were conducted once per section where core conditions allowed.

Whole-Round Multisensor Logger measurements

GRA bulk density, P-wave velocity, and magnetic susceptibility were measured nondestructively with the WRMSL. To optimize WRMSL performance, sampling intervals and measurement integration times were the same for all sensors. The sampling interval was set at 1 cm with an integration time of 3 s for each measurement. GRA performance was monitored by passing a single core liner filled with deionized water through the WRMSL after every core.

In general, measurements are most effective with a completely filled core liner with minimal drilling disturbance. For APC sediment cores, the 66 mm core liner width is generally filled. Sections consisting of discontinuous fragments were not measured with the WRMSL sensors. Sections were run through the WRMSL only if they were longer than 30 cm.

Gamma ray attenuation bulk density

GRA bulk density is an estimate of bulk density based on the attenuation of a gamma ray beam. The beam is produced by a 137Cs gamma ray source at a radiation level of 370 MBq in a lead shield with a 5 mm collimator, which is directed through the whole-round core. The gamma ray detector on the opposite side of the core from the source includes a scintillation detector and an integral photomultiplier tube to record the gamma radiation that passes through the core. The attenuation of gamma rays occurs primarily by Compton scattering, in which gamma rays are scattered by electrons in the formation; the degree of scattering is related to the material bulk density. Bulk density (ρ) determined with this method can be expressed as

- µ = Compton attenuation coefficient,

- d = sample diameter,

- I0 = gamma ray source intensity, and

- I = measured intensity of gamma rays passing through the sample.

The attenuation coefficient and gamma ray source intensity are treated as constants such that ρ can be calculated from I. The gamma ray detector was calibrated with a set of aligned aluminum cylinders of various diameters surrounded by distilled water in a sealed core liner that is the same as that used during coring operations. The relationship between I and the product of µ and d can be expressed as

where B and C are coefficients determined during calibration. Gamma ray counts through each cylinder were determined for a period of 60 s, and the natural log of resulting intensity values was plotted as a function of µd. Here, the density of each aluminum cylinder is 2.7 g/cm3 and d is 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 cm. The WRMSL provided the values of I and µ, and ρ was calculated with the above equation. Recalibration was performed as needed if the deionized water standard after every core deviated significantly (more than a few percent) from 1 g/cm3. The spatial resolution of the GRA densiometer is <1 cm.

Magnetic susceptibility

Magnetic susceptibility (k) is a dimensionless measure of the degree to which a material can be magnetized by an external magnetic field:

where M is the magnetization induced in the material by an external field strength H. Magnetic susceptibility responds to variations in the magnetic composition of the sediment that commonly can be related to mineralogical composition (e.g., terrigenous versus biogenic materials) and diagenetic overprinting. Materials such as clay generally have a magnetic susceptibility several orders of magnitude lower than magnetite and some other iron oxides that are common constituents of igneous material. Water and plastics (core liner) have a slightly negative magnetic susceptibility.

The WRMSL incorporates a Bartington Instruments MS2 meter coupled to a MS2C sensor coil with a 90 mm diameter and operates at a frequency of 452 Hz. A correction factor of 1.174 was provided by Bartington for this diameter and frequency and was applied to magnetic susceptibility measurements. Data shown here and in the database are not corrected for volume effects because of varying sample bulk density values. The instrument was calibrated with a homogeneous mixture of magnetite and epoxy in a 40 cm long piece of core liner to an accuracy of ±5%. Information from Bartington indicates that the MS2C loop has 2.0 cm spatial resolution. Tests reported by Blum (1997) using synthetic cores suggested a full-width half-maximum response of 4.0 to 4.4 cm.

Compressional wave velocity

The PWL measures the ultrasonic P-wave velocity of the whole-round sample residing in the core liner. The PWL transmits a 500 kHz P-wave pulse across the core section at a specified repetition rate. This signal is coupled to the sample by the plastic pole contacts of the transducers clamped to the sides of the core by the linear actuator. Water is used for each measurement to improve coupling between the transducers and the liner. The plastic pole contacts and the pressure applied by the actuator were generally sufficient for reliable P-wave measurement. The transmitting and receiving ultrasonic transducers were aligned so that wave propagation is perpendicular to the long axis of the core section.

The basic relationship for sonic velocity (V) is

where d is the path length of the wave through the core and t is the traveltime. Besides the traveltime through the sample, the total traveltime between the transducers includes three additional components:

- tdelay = time delay related to transducer faces and electronic circuitry,

- tpulse = delay related to the peak detection procedure, and

- tliner = transit time through the core liner.

For routine measurement on whole-round cores inside core liners, the corrected core velocity (Vcore) can be expressed by

- dʹcore = measured diameter of core and liner,

- dliner = liner wall thickness, and

- t0 = measured total traveltime.

The system was calibrated using a core liner filled with deionized water and an aluminum block with known velocity (6295 m/s) and length (76.2 mm).

Traveltime was determined by signal processing software that automatically detects the first arrival of the P-wave signal. Because high background noise makes it challenging for an automated routine to pick the first arrival of a potentially weak signal, the search method skips the first positive amplitude and finds the second positive amplitude using a detection threshold limit typically set to 30% of the maximum amplitude of the signal. The program then finds the preceding zero crossing and subtracts one wave period to determine the first arrival. To avoid extremely weak signals, a minimum signal strength can be set (typically 0.02 V) and weaker signals are ignored. To avoid signal interference at the beginning of the record from the receiver, a delay (typically 0.01 ms) can be set to force the amplitude search to begin in the quiet interval preceding the first arrival. In addition, a trigger (typically 4 V) is selected to initiate the arrival search process, and the number of waveforms to be stacked (typically 50) can also be set. A laser measures the separation of the transducer to derive a signal path length (i.e., core diameter). After corrections for system propagation delay, liner thickness, and liner material velocity, the ultrasonic P-wave velocity is calculated. The software removes any extremely unrealistic velocity values (<900 m/s or >6000 m/s).

Natural Gamma Radiation Logger

The NGRL measures gamma radiation emitted from whole-round core sections that arises primarily from the decay of 238U, 232Th, and 40K isotopes. The main natural gamma radiation (NGR) detector unit consists of 8 sodium iodide (NaI) scintillator detectors. The NaI detectors are covered by 8 cm of lead shielding. In addition, lead separators (~7 cm of low-background lead) are positioned between the NaI detectors. Half of the lead shielding closest to the NaI detectors is composed of low-background lead, whereas the outer half is composed of regular (virgin) lead. In addition to passive lead shielding, the NGRL employs plastic scintillators to suppress the high-energy gamma and muon components of cosmic radiation by producing a canceling signal when these charged particles pass through the plastic scintillators.

A measurement run consisted of eight simultaneous measurements offset by 20 cm each. The quality of the energy spectrum measured in a core depends on the concentration of radionuclides in the sample but also on the counting time, with higher times yielding better spectra. Counting times were 300 s in each of two positions for a total of 10 min. For presentation purposes, the counts are summed over the range of 100–3000 keV. The spatial resolution of the NGR measurements is 18–20 cm (Vasiliev et al., 2011). Sections were run through the NGRL only when the retrieved interval was longer than 50 cm.

The NGRL was calibrated using a source consisting of 137Cs and 60Co and identifying the peaks at 662 (137Cs) and 1330 keV (60Co). Calibration materials were provided by Eckert & Ziegler Isotope Products, Valencia, California (USA). Background measurements of an empty core liner counted for 40,000 s (~10 h) at each measurement position were made upon arrival at the site. Over the 100–3000 keV integration range, background counts averaged 4–5 counts/s.

Section Half Multisensor Logger measurements

The SHMSL measures magnetic susceptibility and spectral reflectance on archive halves. The archive half is placed on the system’s core track. An electronic platform moves along a track above the core section, recording the sample height with a laser sensor. The laser establishes the location of the bottom of the section, and the platform reverses the direction of movement, moving from bottom to top taking MSP and spectral reflectance measurements at 1 cm intervals.

Color reflectance spectrometry

The color reflectance spectrometer uses an Ocean Optics 30 mm integrating sphere and both halogen and LED light sources, which cover wavelengths from ultraviolet through visible to near infrared. Measurements were taken from 380 to 900 nm wavelengths at 2 nm intervals. The approximate 3 s data acquisition offset was applied for the entire scan of the archive half. The data are reported using the red-green-blue and L*a*b* color systems, in which L* is lightness, a* is redness (positive) versus greenness (negative), and b* is yellowness (positive) versus blueness (negative) of the rock. The color reflectance spectrometer calibrates on two spectra, pure white (reference) and pure black (dark). Color calibration was conducted automatically approximately once every 6 h (twice per shift).

Point magnetic susceptibility

MSP was measured with a Bartington MS2K contact probe with a flat, 15 mm diameter, round sensor with a field of influence of 25 mm and an operation frequency of 930 Hz. The instrument averages three measurements from the sensor for each offset, leading to an accuracy of ~5%. As with whole-round measurements, the output displayed by the point magnetic susceptibility sensor must be converted to dimensionless SI units by multiplying by 10−5. The probe is zeroed in air before each measurement location to avoid influence from the metal track. The MSP meter was calibrated by the manufacturer before installation on the ship and was quality checked every ~6 h at the same time as color reflectance sensor calibration.

Thermal conductivity

Thermal conductivity is a measure of the ease at which heat flows through a material and is dependent on composition, porosity, and structure. Thermal conductivity was measured on unconsolidated sediment using the TeKa TK04 unit needle probe (Blum, 1997; Von Herzen and Maxwell, 1959). To insert this probe, a hole was made in the core liner of a whole-round core section at a position based on visual inspection of the core to avoid disturbed regions.

All measurements were made after cores equilibrated to ambient laboratory temperature. After the background thermal drift was determined to be stable, the heater circuit was closed and the increase in the probe temperature was recorded. Temperature-time series were acquired over ~80 s. Thermal conductivity values are based on the observed rise in temperature for a given flux of heat. Three measurements were taken with a cooling time of 10 min between measurements.

Temperature influences thermal conductivity of porous rocks in two competing ways. The thermal conductivity of the rock matrix is inversely related to temperature (Zoth and Haenel, 1988), whereas the thermal conductivity of water increases with temperature (Keenan et al., 1978). Reported thermal conductivity values are at laboratory temperatures and have not been corrected to in situ temperature.

Moisture and density

Several basic quantities of interest (water content, bulk density, dry density, porosity, and void ratio) are most accurately determined through mass and volume determinations on discrete samples. MAD samples were taken from the working half at a frequency of approximately one per section during Expedition 372. In unconsolidated sediments, samples were taken from the core using syringes. Sediment samples were carefully placed in vials that had previously been weighed and had their volume determined. Care was taken to avoid disturbed core material, fill the vial as completely as possible, remove excess material from the outside of the vial, and collect samples as rapidly as possible after core splitting. Immediately after sediment samples were collected, the vials were capped until weighing to prevent moisture loss. As soon as possible after collection, wet sediment mass (Mwet) was measured. Dry sediment mass (Mdry) and volume (Vdry) were measured after drying the samples in a convection oven for >24 h at a temperature of 105° ± 5°C and then cooling in a desiccator for >1 h. A dual-balance system was used to measure both wet and dry masses. Two Mettler-Toledo XS204 balances were used to compensate for ship motion, with one acting as a reference and the other for measurement of the unknown. A standard weight of similar value to the sample was placed upon the reference balance to increase accuracy. The default setting of the balances was 300 measurements (taking ~1.5 min).

Dry volume was measured using a helium-displacement pycnometer with a nominal precision of ±0.04 cm3. The pycnometer system measures dry sample volume using six pressurized, helium-filled chambers. Individual volume measurements were preceded by three purges of the sample chambers with research-grade (99.995% or better) helium heated to 28°C followed by three data acquisition cycles. Each reported value consists of an average of the three measurements.

At the start of the expedition and whenever the helium gas tank was changed, shipboard technicians performed a calibration using stainless steel spheres of known volume. Each pycnometer chamber was tested at least once every 30 samples by running two spheres of known volume in one of the chambers during each use (e.g., as many as 5 sediment samples were tested, and the remaining cell contained the spheres with known volume). The pycnometer chamber was recalibrated if the measured volume was not within 1% of the known volume.

For calculation of sediment bulk density, dry density, grain density, porosity, and void ratio, the traditional Ocean Drilling Program method was used (Method C; Blum, 1997). Water content, porosity, and void ratio are defined by the mass or volume of extracted water before and after removal of interstitial pore water through the drying process. Standard seawater density (1.024 g/cm3) is used for the density of pore water.

Water content (Wc) was determined following the methods of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Designation D2216 (ASTM International, 1990). Corrections are required for salt when measuring the water content of marine samples. In addition to the recommended water content calculation in ASTM D2216 (i.e., the ratio of pore fluid mass to dry sediment mass [percent dry weight]), we also calculated the ratio of pore fluid mass to total sample mass (percent wet weight). The equations for water content are

- Mwet = total mass of the saturated sample,

- Mdry = mass of the dried sample, and

- r = salinity.

Bulk density (ρ) is the density of the saturated samples, where ρ = Mwet/Vwet. The mass (Mwet) was measured using the balance, and Vwet was determined from the pycnometer measurements of dry volume (Vdry) and the calculated volumes of the pore fluid (Vf) and salt (Vsalt):

(Vwet = Vdry + Vf − Vsalt).

Porosity (ϕ) was calculated using

ϕ = (Wc × ρ)/[(1 + Wc) × ρw],

- ρ = calculated bulk density,

- ρw = density of the pore fluid, and

- Wc = water content expressed as a decimal ratio of percent dry weight.

Grain density (ρgrain) was determined from measurements of dry mass and dry volume made in the balance and in the pycnometer, respectively. Mass and volume were corrected for salt using

ρgrain = (Md − s)/[Vd − (s/ρsalt)],

where s is the salt content (in grams) and ρsalt is the density of salt (2.257 g/cm3).

Discrete compressional wave velocity

Discrete P-wave velocity measurements were obtained on the working halves of sediment cores at a frequency of one per section where conditions allowed. The frequency of the transducers is 500 kHz. y- and z-axis measurements were acquired using two pairs of bayonet probes inserted perpendicular and parallel to the axis of the working half, respectively. x-axis measurements were acquired with a caliper-type contact probe with one plastic transducer contact on the face of the working half and the other contact against the core liner. For x-axis measurements, the distance between the transducers was measured by laser (in meters) and velocity values were corrected for liner thickness and velocity.

The signal received through the sample was recorded by the computer attached to the system, and the first arrival was chosen with autopicking software, as described in Compressional wave velocity. The caliper-type contact probe was calibrated each day before measurements with an aluminum block of known velocity. Water was used to calibrate the bayonet probes.

Shear strength

Measurements using the AVS device and a pocket penetrometer provide a profile of variations in strength. The measurements were not performed at in situ stress conditions and thereby underestimate the true undrained peak shear strength in situ. Measurements were made with the vane rotation axis and penetrometer penetration direction perpendicular to the split surface (i.e., parallel to any sedimentary horizontal lamination of bedding present).

Undrained shear strength was measured in fine-grained unconsolidated sediment using the AVS system following the procedures of Boyce (1977). The vane rotation rate was set to 90°/min. Peak undrained shear strength was measured typically once per section. The instrument measures the torque and strain at the vane shaft using a torque transducer and potentiometer. Vane shear strength (Su(v)) (kilopascal) is calculated as

where T is the torque required to cause the material to fail (newton meters) and Kv is the constant depending on vane dimensions (cubic meters) (Blum, 1997).

All AVS measurements reported were obtained using a vane with a height and diameter of 12.7 mm. Failure torque was determined by measuring the degrees of rotation of one of four torsional springs and a manufacturer-specified linear calibration equation relating the rotation angle to torque for the particular spring being used. Selection of the appropriate spring was based on the anticipated shear strength of the material. Vane shear results were generally considered reliable for shear strength values less than ~150–200 kPa, above which excessive cracking and separation of the core material occurred.

A pocket penetrometer was used to measure compressive strength. Penetration measurements were all conducted on the split-core face. As with the vane shear, this means that results were measured parallel to any horizontal bedding or lamination. The Geotester STCL-5 pocket penetrometer is a spring-operated device used to measure compressive strength by pushing a 0.25 inch (6.4 mm) diameter probe 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) deep (to the red marker) below the split-core surface. The mechanical scale of compressive strength (Δσf) is in units of kilograms per square centimeter, which are converted into units of kilopascals for reporting as follows:

Unconfined shear strength (Su(penet)) is approximately related to compressive strength by the following equation (Blum, 1997):

A 1 inch (25.4 mm) diameter adapter foot was used for measuring in very soft sediment. It provided a 16× increase in area. Results in the database are corrected for the larger area by dividing by 0.0625. The maximum compressive strength that can be measured with the pocket penetrometer is 220 kPa. Measurements using the penetrometer are typically performed once per section.

Downhole measurements

In situ pressure and temperature measurements