Kodaira, S., Conin, M., Fulton, P., Kirkpatrick, J., Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., and the Expedition 405 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 405

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.405.103.2025

Site C00191

![]() C. Regalla,

C. Regalla,

![]() K. Ujiie,

K. Ujiie,

![]() P. Fulton,

P. Fulton,

![]() J. Kirkpatrick,

J. Kirkpatrick,

![]() M. Conin,

M. Conin,

![]() S. Kodaira,

S. Kodaira,

![]() N. Okutsu,

N. Okutsu,

![]() L. Maeda,

L. Maeda,

![]() S. Toczko,

S. Toczko,

![]() N. Eguchi,

N. Eguchi,

![]() P. Bellanova,

P. Bellanova,

![]() C. Brown,

C. Brown,

![]() M. Brunet,

M. Brunet,

![]() M. Castillo,

M. Castillo,

![]() Y.-C. Chang,

Y.-C. Chang,

![]() M.-L. Doan,

M.-L. Doan,

![]() J. Everard,

J. Everard,

![]() A. Fintel,

A. Fintel,

![]() J. Ford,

J. Ford,

![]() R. Fukuchi,

R. Fukuchi,

![]() A. Gough,

A. Gough,

![]() H. Guo,

H. Guo,

![]() D. Gürer,

D. Gürer,

![]() R. Hackney,

R. Hackney,

![]() M. Hagino,

M. Hagino,

![]() Y. Hamada,

Y. Hamada,

![]() H. Hosono,

H. Hosono,

![]() A. Ijiri,

A. Ijiri,

![]() M. Ikari,

M. Ikari,

![]() T. Ishikawa,

T. Ishikawa,

![]() M. Iwai,

M. Iwai,

![]() T. Jeppson,

T. Jeppson,

![]() M.-J. Jurado,

M.-J. Jurado,

![]() N. Kamiya,

N. Kamiya,

![]() T. Kanamatsu,

T. Kanamatsu,

![]() A. LaPlante,

A. LaPlante,

![]() W. Lin,

W. Lin,

![]() A. Miyakawa,

A. Miyakawa,

![]() Y. Morono,

Y. Morono,

![]() Y. Nakamura,

Y. Nakamura,

![]() U. Nicholson,

U. Nicholson,

![]() H. Okuda,

H. Okuda,

![]() P. Pei,

P. Pei,

![]() C. Pizer,

C. Pizer,

![]() T. Rasbury,

T. Rasbury,

![]() R.V.M. Robertson,

R.V.M. Robertson,

![]() C. Ross,

C. Ross,

![]() S. Satolli,

S. Satolli,

![]() H. Savage,

H. Savage,

![]() K. Schaible,

K. Schaible,

![]() S. Shreedharan,

S. Shreedharan,

![]() H. Sone,

H. Sone,

![]() C. Sun,

C. Turel,

C. Sun,

C. Turel,

![]() T. Uchida,

T. Uchida,

![]() A. Yamaguchi,

A. Yamaguchi,

![]() Y. Yamamoto,

Y. Yamamoto,

![]() T. Yoshimoto,

T. Yoshimoto,

![]() J. Zhang,

A. Wspanialy,

J. Zhang,

A. Wspanialy,

![]() E. Le Ber,

E. Le Ber,

![]() M.B. Rydzy, and

N. Schuba

2

M.B. Rydzy, and

N. Schuba

2

1 Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Fulton, P., Kirkpatrick, J., Conin, M., Kodaira, S., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., Bellanova, P., Brown, C., Brunet, M., Castillo, M., Chang, Y.-C., Doan, M.-L., Everard, J., Fintel, A., Ford, J., Fukuchi, R., Gough, A., Guo, H., Gürer, D., Hackney, R., Hagino, M., Hamada, Y., Hosono, H., Ijiri, A., Ikari, M., Ishikawa, T., Iwai, M., Jeppson, T., Jurado, M.-J., Kamiya, N., Kanamatsu, T., LaPlante, A., Lin, W., Miyakawa, A., Morono, Y., Nakamura, Y., Nicholson, U., Okuda, H., Pei, P., Pizer, C., Rasbury, T., Robertson, R.V.M., Ross, C., Satolli, S., Savage, H., Schaible, K., Shreedharan, S., Sone, H., Sun, C., Turel, C., Uchida, T., Yamaguchi, A., Yamamoto, Y., Yoshimoto, T., Zhang, J., Wspanialy, A., Le Ber, E., Rydzy, M.B., and Schuba, N., 2025. Site C0019. In Kodaira, S., Conin, M., Fulton, P., Kirkpatrick, J., Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., and the Expedition 405 Scientists, Tracking Tsunamigenic Slip Across the Japan Trench (JTRACK). Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 405: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.405.103.2025

2 Expedition 405 Scientists’ affiliations.

1. Background and objectives

1.1. Objectives

The 11 March 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku-oki earthquake was one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded. The earthquake involved an unusually large slip at shallow depths along the plate boundary fault, which was a key factor in generating the devastating tsunami that followed (e.g., Kodaira et al., 2020). However, the physical, mechanical, and hydrologic properties that allowed for this large shallow slip remain poorly understood. The primary objectives of International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 405 (Tracking Tsunamigenic Slip Across the Japan Trench [JTRACK]) were to determine the conditions and processes that facilitated extremely large slip on the shallow subduction interface during the 2011 earthquake and to evaluate spatiotemporal changes in stress state, healing, and hydrologic properties in the ~13 y following the earthquake. Understanding the factors that control the magnitude of shallow earthquake slip is a priority for the geoscience community and essential for mitigating the risks of future tsunamigenic earthquakes at the Japan Trench and other subduction zones worldwide.

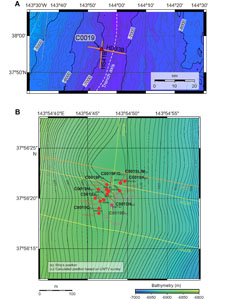

Expedition 405 revisited Site C0019 (Figure F1), which was initially drilled approximately 1 y after the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake during Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 343/343T (Japan Trench Fast Earthquake Drilling Project [JFAST]). This site was selected to access samples across the frontal prism, décollement, and underthrust section in the region of large-magnitude shallow slip during the earthquake. Prior drilling operations at Site C0019 during Expedition 343/343T, although successful, included only partial transects across the lower prism and décollement, with limited core recovery and logging-while-drilling (LWD) data types. Advances in borehole instrumentation drilling technologies since Expedition 343/343T permitted collection of higher resolution LWD data and better recovery of higher quality cores in the challenging deepwater environment of the Japan Trench. New drilling at Site C0019 during Expedition 405 was designed with three sets of objectives to achieve the expedition’s scientific goals. First, LWD operations collected high-resolution logging data across the prism, décollement, and underthrust plate in a transect to the top of the subducted oceanic crust. Second, coring operations recovered sediment and rock from the entire frontal prism, the décollement, underthrust sediment, and oceanic basalt. Third, two borehole temperature observatories were installed to monitor borehole fluid conditions both during and after drilling operations. These operations at Site C0019 provide critical data necessary to determine the structure and composition of the prism, décollement, and underthrust plate; to quantify stress state and changes in stress over time; and to quantify subduction zone hydrogeology across the décollement and prism. Collectively, the results from Site C0019 will reveal the conditions that lead to large shallow tsunamigenic slip in Tohoku and provide critical information that could directly influence earthquake and tsunami hazard assessments globally.

1.2. Background

1.2.1. Geologic setting

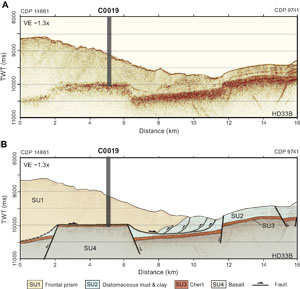

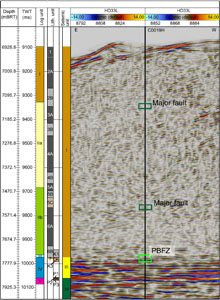

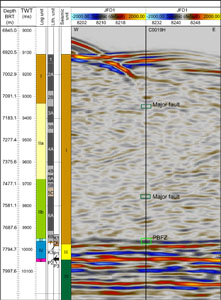

The Japan Trench subduction zone is located off the east coast of northeast Japan where the Pacific plate subducts beneath Japan at a rate of 85 mm/y (DeMets et al., 2010; Argus et al., 2011). The plate margin is characterized by an ~8 km deep trench with a shallowly dipping (~8°) décollement separating the subducting (Pacific) and overriding North American/Okhotsk plate (von Huene et al., 1982). The structure and composition of the prism, décollement, and underthrust material are largely constrained based on prior multichannel seismic profile data, coring during Expedition 343, and correlations to units recovered during Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) Legs 56 and 57 at Site 436. The frontal prism consists of a low-velocity (VP = 2–3.5 km/s), ~20–30 km wide, seismically chaotic sedimentary wedge (Kodaira et al., 2017; Tsuru et al., 2002). Because of time limitations, Expedition 343 began continuous coring at Site C0019 at ~680 meters below seafloor (mbsf). Sediments collected from ~680 to 800 mbsf consist of ~0–15 Ma biogenic and siliciclastic mudstones (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013a; Rabinowitz et al., 2015; Regalla et al., 2019) and have been interpreted as comprising a frontal accretionary prism (von Huene et al., 1994; Regalla et al., 2019). The décollement at Site C0019 is visible in seismic reflection lines as a high-amplitude semicontinuous reflection that separates undeformed shallowly dipping strata in the subducting plate from deformed material in the overriding plate (Nakamura et al., 2013, 2020). At the position of Site C0019, the décollement occurs above a subducted host block (Chester et al., 2013; Nakamura et al., 2013). Cores recovered from Site C0019 during Expedition 343 indicated that at the décollement zone there is a less than 5 m thick zone of sheared clays with scaly fabrics and sharp planar faults surrounded by a few tens of meters of fractured mudstones and several additional faults (Chester et al., 2013; Kirkpatrick et al., 2015; Keren and Kirkpatrick, 2016). Materials within this zone have been correlated to pelagic clays and clayey mudstones at the base of the incoming sediment section, as represented by the stratigraphy at Site 436 (Chester et al., 2013; Kameda et al., 2015; Rabinowitz et al., 2015). Underthrust material below the décollement consists of two seismically identified units: SU3 and SU4. Seismic Unit SU3 is characterized by relatively strong reflections, and the base of this unit is marked by a high-amplitude semicontinuous reflection. Unit SU3 is correlated to cherts recovered below the décollement during Expedition 343 as well as those recovered at the base of the incoming sediment section at Site 436 (Nakamura et al., 2013; Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013a). Unit SU4 is a seismic basement, which is interpreted to be the igneous basaltic crust of the Pacific plate. This unit was not drilled during Expedition 343 or Legs 56 and 57.

1.2.2. Motivation for hole positioning

Site C0019 is positioned within the overriding plate approximately 6 km landward of the Japan Trench axis, near the intersection of Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) Multichannel Seismic Lines HD33B and HS41B (Figure F1). Drilling at this site allows direct access to the materials above, within, and below the shallow plate boundary décollement that experienced large shallow slip during the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake (Figure F2). This same site was drilled previously during Expedition 343, but coring intervals were very limited because of the short duration of coring (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013a). New drilling activities at Site C0019 during Expedition 405 aimed for continuous data collection across the prism, décollement, and underthrust plate and direct comparison of time variable properties within the high slip region.

Drilling activities at Site C0019 during Expedition 405 were divided into four phases: installation of a temperature observatory by reoccupying Expedition 343 Hole C0019D, collection of LWD data, continuous coring, and installation of a second temperature observatory. The first observatory reoccupied Expedition 343 Hole C0019D to monitor temperature and fluid conditions near the décollement and capture perturbations to the formation conditions caused by Expedition 405 drilling. A complete transect across the entire prism, décollement, and underthrust sequence was achieved by separating LWD and coring operations in multiple holes, allowing for use of different borehole assemblies that were best suited for the variable material properties with depth (Figure F1). We note that drilling depths are herein reported as either meters below sea level (mbsl), meters below sea floor (mbsf), or meters below rotary table (m BRT), where the rotary table is 28.5 m above sea level. LWD data collection was completed in the shallow prism in Hole C0019F without bottom-hole assembly (BHA) rotation (0–86 mbsf; 6926.4–7012.4 m BRT) and then subsequently across the prism, décollement, and lower plate in Hole C0019H with BHA rotation (90–980 mbsf; 7016–7906 m BRT). Coring included small-diameter rotary core barrel (SD-RCB) coring in Hole C0019J, which transected the prism to the décollement (82–830 mbsf; 7009.5–7757.5 m BRT), Hole C0019K, which transected the décollement and underthrust sequence (815–875.5 mbsf; 7719–7779.5 m BRT), and Hole C0019P, which transected the lower cherts and upper basalts of the underthrust Pacific plate. The hydraulic piston coring system (HPCS) sampled the shallow prism in Holes C0019L and C0019M (0–114.5 mbsf; 6905–7019.5 m BRT). Finally, the second observatory was installed in the newly drilled Hole C0019P for long-term monitoring.

The locations of holes at Site C0019 were initially designed to be aligned along a trend of ~025°–205°, parallel to the average strike of bedding observed in LWD data from Expedition 343 (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013a) and approximately perpendicular to the local convergence direction (~110°). Positioning of holes along a strike transect was chosen to facilitate correlation of structures between LWD, core, and observatory holes to aid in data analysis and real-time adjustment of operations to target specific intervals of interest. The Expedition 405 strike transect is located ~30 m west of a parallel transect drilled during Expedition 343 (Holes C0019A–C0019E; Figure F1). Holes C0019F–C0019H, C0019J, and C0019Q were sighted along this strike transect and maintain the targeted ~025°–205° trend. Hole C0019N was positioned 30 m west of the strike line near the seabed position of LWD Hole C0019H. Hole C0019K is along the same trend but located on the previous Expedition 405 transect, north of the holes drilled in 2012. HPCS Holes C0019L and C0019M were positioned ~20 m east of the Expedition 405 strike transect. Their position was chosen to be on a bathymetrically higher portion of the seafloor than LWD, SD-RCB coring, and observatory holes, with the objective of obtaining a more complete shallow sedimentary record.

2. Operations

Daily summaries of operations at Site C0019 are listed in Table T1. Daily operations summaries can be found in DAILYRPT in Supplementary material. Coring intervals for Holes C0019J, C0019K, C0019L/C0019M, and C0019P are summarized in Tables T2, T3, T4, and T5, respectively.

2.1. Port call and transit to Site C0019

Expedition 405 began at 1000 h on 6 September 2024, departing from the Port of Shimizu, Shizuoka Prefecture. The drilling vessel (D/V) Chikyu arrived at Site C0019 on 7 September, and all preparations related to setting dynamic positioning were completed at 1530 h 8 September.

2.2. Hole C0019D

Making up and running the Re-engaging Tool to connect to the Hole C0019D wellhead started at 1730 h on 8 September 2024 while drifting from around 4 nmi upstream of the surface current and reached 6353.0 m at 0930 h. The underwater TV camera (UWTV) system was run down at 0930 h on 9 September but was recovered from 2107 meters below mean sea level (m MSL) because of lost communication with a sonar. The UWTV was run down again at 1845 h after the sonar was replaced with a spare one. Running the Re-engaging Tool was resumed when the UWTV reached 6000 m MSL at 2045 h. A seabed survey and search for the wellhead was conducted starting at 0615 h on 10 September. It took almost 13 h to find the wellhead. The Re-engaging Tool was landed on the wellhead at 2030 h. Before running the sensor assembly in the hole, two dummy assembly runs were made to confirm the borehole condition and the bottom depth. Making up and running the sensor assembly in the hole started at 0900 h on 12 September, and landing the sensor assembly was confirmed at 1715 h. All operations in Hole C0019D were completed when the Re-engaging Tool was pulled out to the surface at 1930 h on 13 September.

2.3. Hole C0019F

Drilling down without rotating a BHA is required to drill a borehole straight down when drilling in ultradeep water, whereas a LWD BHA needs rotation to acquire the hole borehole image data. The target depth for the first LWD hole was 100 mbsf. Making up and running LWD started at 0000 h on 14 September 2024 and continued to 0100 h on 15 September while LWD signal tests were conducted at 138.0, 3009.0, 6004.5, 6542.5, 6772.5, and 6851.0 m BRT. The UWTV was run down at 0100 h, and a seabed survey was conducted from 0545 to 1000 h. Seabed surveys were initiated by finding Hole C0019D to use as a reference position. The location for LWD operations was finalized ~30 m north of Hole C0019D. Spud-in of Hole C0019F was achieved at 6926.5 m BRT at 1000 h, followed by washing down to 6936.5 m BRT (10.0 mbsf). Drilling down with rotation started at 1500 h and reached the target depth of 7012.4 m BRT (86.0 mbsf) at 2145 h. The LWD BHA was pulled out to 6921.0 m BRT at 2215 h for the next LWD operation.

2.4. Hole C0019G

The ship position for Hole C0019F was used for Hole C0019G because the latter hole targeted a deeper section of the formation. The LWD BHA tagged Hole C0019G at 6924.0 m BRT at 2215 h on 15 September 2024 but showed mud pulse telemetry signal failure from the measurement-while-drilling (MWD) tool (TeleScope) at 6936.5 m BRT (12.5 mbsf) at 2300 h. Troubleshooting efforts, including downlink and increasing the pump rate to 500 gal/min, were attempted but did not resolve the signal failure. The decision was made to pull the BHA to the surface at 0130 h on 16 September, and the BHA was recovered on deck at 1900 h.

2.5. Hole C0019H

A new LWD BHA was made up with the backup TeleScope and mud motor, and it was run in the hole at 1900 h on 16 September 2024. Running in the hole continued until 0045 h on 18 September while signal tests were conducted at 117.0, 1274.0, 2404.0, 3561.0, 4667.5, 5812.0, and 6837.0 m BRT. The UWTV was run down to 6800 m MSL at 0530 h to finalize the hole location. Hole C0019H was established a few meters southwest of Holes C0019F and C0019G at 0657 h on 18 September. Washing down without rotation was maintained to 7016.0 m BRT (90.0 mbsf) at 1215 h. Drilling down with the LWD BHA started at 1700 h after the UWTV was recovered. The LWD BHA reached the target depth of 7906.0 m BRT (980.0 mbsf) at 0730 h on 21 September and was pulled out of the hole to 7784.0 m BRT (858.0 mbsf). Overpull and hydraulic power swivel (HPS) stall were observed at 7804.0 and 7791.5 m BRT, respectively. Repeat logs were acquired from 7780.0 to 7572.0 m BRT (854.0–646.0 mbsf) and completed at 2130 h. The LWD BHA was recovered on deck at 1700 h on 22 September.

2.6. Hole C0019J

The vessel started sailing back to Site C0019 from the Typhoon 17 (JEBI) evacuation area at 1100 h on 2 October 2024 while maintenance and preparations for coring operations were conducted. An SD-RCB BHA with dual drill collars was made up and run in the hole at 2300 h on 3 October and reached 6832.0 m BRT at 1930 h on 4 October. The center bit was dropped after break circulation, followed by running the UWTV down. A seabed survey was held to confirm the hole location, which was finalized ~30 m southwest of Hole C0019H. Hole C0019J was spudded in at 6927.5 m BRT at 0227 h on 5 October and washed/drilled down with the SD-RCB BHA to the coring starting depth of 7009.5 m BRT (82.0 mbsf). The center bit was recovered at 1930 h, and coring operations began. The first core of this expedition, Core 405-C0019J-1K, was on deck at 0045 h on 6 October. Coring operations continued to 2100 h on 23 October with two interruptions.

The first interruption was caused by waiting on weather. The SD-RCB BHA was pulled out from 7209.0 to 6963.5 m BRT (281.5–36.0 mbsf) after recovering Core 405-C0019J-21K on deck at 2200 h on 9 October to allow an emergency pull out of the hole in case maintaining dynamic positioning became difficult. During the waiting on weather period, >20 m/s wind (gusts) with ~6 m wave height were observed from 2300 to 0200 h on 11 October. The SD-RCB BHA was then run back to the bottom at 0500 h, and coring operations resumed. The second interruption occurred after Core 74K was recovered on deck at 0615 h on 20 October. A passing cold front left strong winds and ~6 m wave height on site while the drilling depth approached the estimated depth of the most important formations to be recovered. A short wiper trip was conducted to check and clean the borehole. While pulling the SD-RCB BHA out from 7712.0 to 7450.0 m BRT (784.5–522.5 mbsf), damage was found on the Lower Main Roller on the FWD side of the Traveling Block Dolly at 0900 h. The short trip was resumed after it was replaced with a new Main Roller Assembly at 1500 h. Tight spots were observed as discrete peaks in weight on bit from 7560.0 to 7583.0 m BRT and from 7712.0 to 7715.0 m BRT. To remedy this, the hole was reamed down and then swept out with 10 and 15 m3 of seawater gel, respectively. Coring resumed at 0030 h on 21 October and reached the target depth of 7757.5 m BRT (830.0 mbsf) at 2100 h on 23 October.

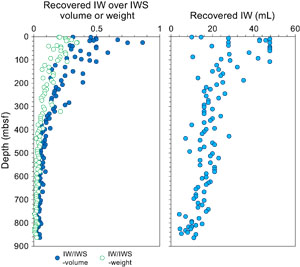

The coring advance was set 9.5 or 10 m for Cores 405-C0019J-1K through 74K; however, this coring advance was halted to prevent missing or damaging the fragile formation when high standpipe pressure was observed for Cores 75K–88K and instead set to 2.0–4.5 m advance. In total, 88 cores (total length of initial recovery = 370.5 m) were collected from 82.0 to 830.0 mbsf (748.0 m interval) with an average recovery of 49.5% (Table T2). Because of incomplete recovery of key intervals in the décollement and underthrust section, we decided to core a second plate boundary interval east of Hole C0019H near the Expedition 343 transect in Hole C0019K. The SD-RCB BHA was pulled out of Hole C0019J to 6801.0 m BRT at 0200 h on 24 October and kept close to the seafloor while moving to the next hole.

2.7. Hole C0019K

The UWTV was run to 6800 m MSL while dropping the center bit at 1530 h on 24 October 2024. Hole C0019K, which lies ~30 m east of Hole C0019H, was spudded in at 1630 h. The SD-RCB BHA reached 7719.0 m BRT (815.0 mbsf) at 0730 h on 26 October. The center bit was recovered to the surface after a short trip between 7719.0 and 7544.0 m BRT, and coring began at 1445 h and continued until 1115 h on 30 October. The coring advance varied between 2.0 and 6.0 m because of adjustments when standpipe pressure increased so that the chances of missing the collection of fragile formations would be minimized. In total, 17 cores (total length of initial recovery = 41.6 m) were collected from 815.0 to 875.5 mbsf (60.5 m interval) with an average recovery of 68.8% (Table T3). The SD-RCB BHA was pulled out to the surface at 0930 h on 31 October.

2.8. Hole C0019L

As at Site C0026, at least two holes were planned for HPCS operations to sample the surface sediment and mudline. A HPCS BHA was made up and run in the hole to 6893.0 m BRT at 1100 h on 12 November. A seabed survey with the UWTV was carried out from 1430 to 1900 h to check the shallow coring hole and prepare for additional planned deep coring operations with the SD-RCB. Hole C0019L was shot from above the seabed at 2025 h, and the inner barrel was pulled out using the drawworks assist. Core 405-C0019-1H successfully collected the surface sediment and mudline with bottom water at 2130 h (Table T4).

2.9. Hole C0019M

Hole C0019M was shot from above the seabed at 2232 h on 12 November 2024. Core 405-C0019M-1H was retrieved with the mudline and bottom water at 2400 h. Coring continued with full stroke for Cores 1H–6H, although assistance from the drawworks was required to pull out the inner barrel. Partial penetration while shooting and overpull while pulling the inner barrel were observed for Cores 7H–10H. Overdrilling while pulling with the drawworks was applied to pull out these cores. Core 10H showed 9.82 m of the initial core length even though the coring advance was only 2.5 m.

The coring system was changed to the extended shoe coring system (ESCS) for Core 405-C0019M-11X. ESCS coring continued through Core 14X with a 9.5 m coring advance. In total, 14 cores (total length of initial recovery = 95.0 m) were collected from 0 to 114.5 mbsf (114.5 m interval) with an average recovery of 83.0% (Table T4). The HPCS BHA was pulled out of the hole to the surface at 2300 h on 15 November.

2.10. Hole C0019N

To minimize the risk of getting stuck in the hole based on lessons learned from operations in Hole C0026A, an SD-RCB BHA without any drill collars was built up to collect cores below the chert layers. The SD-RCB BHA was made up and run in the hole at 2315 h on 16 November 2024, and it reached 6825.0 m BRT at 2130 h on 17 November. The center bit was dropped before running the UWTV at 0100 h on 18 November. Spud-in of Hole C0019N was performed at 6924.0 m BRT ~30 m west northwest of Hole C0019H at 0815 h, followed by washing down to 6974.0 m BRT (50.0 mbsf). Drilling down with the SD-RCB BHA began at 1530 h after the UWTV was recovered to the surface and continued to 7752.5 m BRT (828.5 mbsf) with an average rate of penetration (ROP) of ~55 m/h. A short trip was carried out from 7752.5 to 7487.5 m BRT because the ROP decreased from 0430 to 0815 h on 20 November. Drilling paused because of maintenance for a HPS motor malfunction and then resumed at 1445 h from 7785.5 m BRT. The ROP dropped and intermittently arrested with observed torque spikes. To continue drilling, the hole was swept up and down, but no progress was made from 7825.0 m BRT (901 mbsf).

At 0915 h on 21 November, the decision was made to quit drilling ahead instead of coring at the current depth. The center bit was recovered at 1300 h, and we observed that no cutters remained. After circulating bottoms up, the core barrel was dropped and we attempted to cut a core at 1530 h. The coring barrel was retrieved at 2200 h without any advance. Junk cuttings were found in the core liner, and the decision was made to pull out of the hole. A free-fall funnel was deployed at 0230 h on 22 November, when the BHA pulled out to 7024.0 m BRT (100.0 mbsf). The UWTV was run and recovered to let the free-fall funnel land properly at 1400 h. The BHA was recovered to the surface at 0545 h on 23 November. The top section of the coring bit was found to be severely worn out.

2.11. Hole C0019P

We decided that the center bit was not strong enough to drill through the chert layers and applied the following operations plan:

- Drill down with a noncoring bit.

- Deploy a free-fall funnel.

- Reenter the hole with the SD-RCB BHA.

- Core below the chert layers.

The 8½ inch drilling BHA was made up and run in the hole at 0745 h on 23 November 2024. The UWTV seabed survey was performed from 1000 to 1630 h on 24 November. The 8½ inch drilling BHA was spudded into Hole C0019P at 1630 h and washed down from 6920.0 to 6970.0 m BRT (0–50 mbsf). Drilling down started at 0600 h after the UWTV was recovered to the surface and reached the planned coring depth of 7850.0 m BRT (930.0 mbsf) at 2100 h on 26 November. A free-fall funnel was deployed when the 8½ inch drilling BHA was pulled out to 7020.0 m BRT (100.0 mbsf). Mechanical trouble occurred while pulling out of the hole to 3462.0 m BRT at 1400 h on 27 November. Two bolts connecting the 750T Elevator and Adapter sheared and dropped onto the rig floor. The Elevator was replaced to 500T, and we resumed pulling out the 8½ inch drilling BHA to the surface at 0500 h on 28 November. The 750T Elevator was repaired with spare parts and set back again at 0345 h on 29 November.

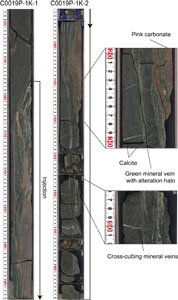

The SD-RCB BHA with a new coring bit and without drilling collars was made up and run at 0845 h, and it reached 6830.0 m BRT at 0300 h on 30 November. The UWTV found the free-fall funnel at 0730 h, which tilted while we attempted reentry at 1200 h. We managed to pass through the free-fall funnel and successfully reentered Hole C0019P at 1730 h while adjusting the vessel position and pushing with the BHA. The UWTV was recovered to the surface at 2100 h, and running the SD-RCB BHA began. The center bit was recovered to the surface at 1015 h on 1 December, followed by conducting circulation and then bottoms up. Coring operations began at 1215 h, and the last core was recovered on deck at 2330 h on 2 December. Five cores were collected from 930.0 to 946.4 mbsf (16.4 m interval) with various advances between 0.9 and 5.0 m and an average recovery of 76.5% (Table T5). The SD-RCB BHA was pulled out to the surface at 2115 h on 3 December. With this, all coring operations for this expedition were complete.

2.12. Hole C0019Q

The operations to install the temperature sensor assembly consisted of five steps:

- Jetting a 13⅜ inch casing with a 20 inch wellhead.

- Drilling down to the target depth.

- Reentering and running a 4½ inch tubing in the hole.

- Running, landing, and releasing the sensor assembly in the hole by coring line.

- Landing and releasing the 4½ inch tubing from the drill string.

Preparing the BHA for 13⅜ inch casing with the 20 inch wellhead, jetting, and drill ahead tool (DAT) in one pipe trip (the jetting and DAT BHA) began at 2115 h on 3 December 2024. The vessel moved to Site C0026 and recovered all transponders while preparing the jetting and DAT BHA.

The jetting and DAT BHA was made up and run at 1630 h on 4 December, and it reached 6828.0 m BRT at 0400 h on 6 December. Spud-in of Hole C0019Q was performed at 6928.0 m BRT at 1015 h after a UWTV seabed survey. The 13⅜ inch casing with 20 inch wellhead was successfully jetted into the planned depth of 6970.0 m BRT (42.0 mbsf) at 1415 h. After releasing the DAT from the wellhead housing was confirmed at 2330 h, the UWTV was recovered to the surface at 0400 h on 7 December. The DAT drilled from 7567.0 to 7853.0 m BRT (639.0–925.0 mbsf) after washing down to 7003.0 m BRT (75.0 mbsf) at 1230 h on 8 December, followed by short trips between 7853.0 and 7474.0 m BRT and spotting 20 m3 of seawater gel at 1800 h, and was finally recovered to the surface at 2230 h on 9 December.

A 4½ inch tubing assembly was made up and run starting at 0045 h on 10 December. The UWTV was run to 7 m above the shoe, where the 4½ inch tubing assembly reached 6873.0 m BRT. The Hole C0019Q wellhead was found, and the 4½ inch tubing assembly reentered the hole at 2330 h on 11 December. After confirming the 4½ inch tubing assembly landed on the casing hanger of the wellhead, we attempted to run the sensor assembly. However, the sensor assembly could not pass through 6915.5 m BRT. The 4½ inch tubing assembly with sensor assembly was pulled out of the hole to the surface, and we found two sensors (#104 and #123) were stuck in a narrow part of the casing hanger of the 4½ inch tubing assembly at 1730 h on 13 December.

The 4½ inch tubing assembly was run and reentered Hole C0019Q again at 1800 h on 14 December. The sensor assembly, with a slightly heavier weight of sinker bars (from 15 to 30 kg) to avoid the same kind of failure, was made up and run in the hole with pumping, and it successfully landed on the sensor hanger. Jarring down was applied to release the sensor hanger from the sinker bar, and we confirmed the release by coring line tension at 0230 h on 15 December. The hydraulic assist running tool (HART) was activated to release the 4½ inch tubing assembly. Landing and releasing were confirmed visually by the UWTV at 1145 h. Pulling the HART out of the hole to the surface was completed at 0745 h on 16 December.

2.13. Transit to Shimizu port

The vessel started to sail back to the Port of Shimizu after all four transponders at Site C0019 were recovered at 1345 h on 17 December 2024 and arrived at the standby point off the Port of Shimizu at 1300 h on 19 December. The expedition was completed after docking quayside at the Port of Shimizu at 1000 h on 20 December.

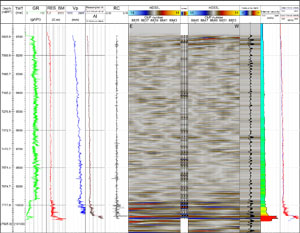

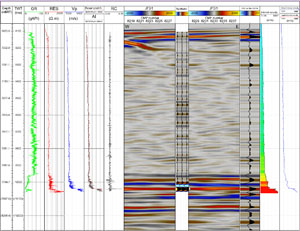

3. Logging while drilling

Three holes (C0019F–C0019H) were drilled for LWD measurements at Site C0019. Logging data were acquired using an LWD/MWD assembly that consisted of the SLB TeleScope, MicroScope, and SonicScope tools (see Logging while drilling in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025]). Logging data were acquired in Holes C0019F and C0019H. Hole C0019F was drilled to a maximum depth of 7022.7 m BRT (96.3 mbsf) to obtain LWD/MWD data and LWD images from the shallow strata. Hole C0019G was abandoned because of technical difficulties with the mud-pulse telemetry module of the TeleScope tool, which meant that no real-time data were transmitted. Following disconnection from the BHA, drilling stopped and the BHA was recovered. No data are available for Hole C0019G. Hole C0019H was jetted down to 7014 m BRT (88.3 mbsf) and then drilled to total depth at 7905.7 m BRT (980 mbsf) to obtain a full suite of LWD/MWD data through the upper plate down to the basalts of the incoming plate. The interval 7572–7774 m BRT was relogged while tripping out to acquire additional resistivity image logs.

3.1. Data and log quality

See Logging while drilling in the Expedition 405 methods chapter (Kirkpatrick et al., 2025) for a detailed description of operations, tools, and data processing.

3.1.1. Hole C0019F

3.1.1.1. Available data

Hole C0019F was drilled to 96.3 mbsf and logged with MWD data, which provided a limited subset of the LWD data in real time. When the LWD tools were recovered on the rig floor, recorded mode data were successfully downloaded and processed.

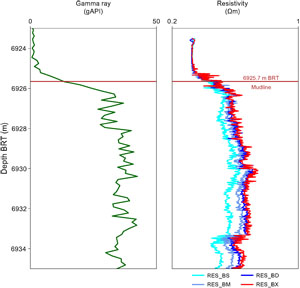

3.1.1.2. Depth shift

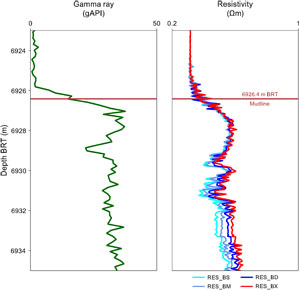

The mudline was identified from the midpoint of the first significant break in the gamma ray and resistivity logs (Figure F3). A mudline was picked at 6926.4 m BRT in Hole C0019F. All LWD data were converted to the LWD depth below seafloor (LSF) depth scale. In this section, LSF depths are referred to as mbsf, based on the mudline depth.

3.1.1.3. Logging data quality

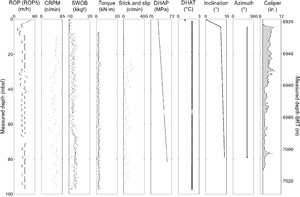

Figure F4 shows an overview of the log QC. The use of rotary drilling in soft sediments may lead to significant deviation of the borehole. Static borehole survey points were scarce but showed that the borehole was inclined by 8° below 4 mbsf. The other drilling parameters show that the borehole was drilled smoothly with an average ROP of ~30 m/h.

Logging data quality is strongly dependent on the borehole diameter and therefore rugosity. To evaluate borehole conditions, SLB provided an electrical caliper (e-caliper) pseudo-log derived from the MicroScope resistivity data at various investigation depths using a proprietary method. This log was used as an indicative measure of the borehole diameter and shape. Intervals where the diameter exceeded the drill bit size (8.5 inches; 21.59 cm) indicate enlargement aligned along the azimuth of the borehole. The logs indicated that the upper section of LWD data from seafloor to around 20–40 mbsf was affected by poor borehole conditions, with both image logs and the e-caliper log indicating consistent hole enlargement.

Resistivity images were acquired from the seafloor to 86 mbsf (Figure F5). The upper 20–40 m of the ultrahigh-resolution images (UHRIs) are poor quality due to poor borehole conditions in the shallow interval. The images from 40 to 80 mbsf are good quality. Throughout the entire logged interval of Hole C0019F, borehole image quality was severely affected in washed out sections. Poor borehole condition and eventually poor tool centralization and contact between the MicroScope tool electrodes and formation resulted in bad and irregular resistivity readings. This resulted in typical washed-out images. Resistivity images from the extra deep, deep, medium, and shallow buttons are of similar quality but have lower resolution.

3.1.2. Hole C0019G

3.1.2.1. Available data

Hole C0019G was drilled with the LWD/MWD tools. Unfortunately, because of a technical issue with the TeleScope tool, no data points were transmitted in real time through mud-pulse telemetry. Following disconnection with the BHA, drilling stopped and the BHA was recovered. No LWD data are available for Hole C0019G.

3.1.3. Hole C0019H

3.1.3.1. Available data

Hole C0019H was drilled to 980 mbsf, and the borehole was logged successfully with the LWD/MWD tools. The hole was jetted down to ~90 mbsf to avoid deviation in the poorly consolidated shallow section. This meant that continuous image logs were not obtained for the upper ~90 m because the mud motor powering the LWD tools was not active during jetting. MWD data were transmitted in real time with a limited set of LWD data through the mud-pulse telemetry system. When the LWD tools were recovered on the rig floor, memory data were successfully downloaded and processed.

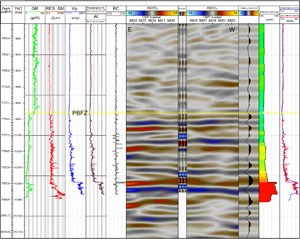

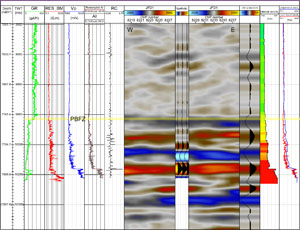

3.1.3.2. Depth shift

The mudline was identified from the midpoint of the first significant break in the gamma ray and resistivity logs (Figure F6). A mudline was picked at 6925.7 m BRT in Hole C0019H. All LWD data were converted to the LSF depth scale.

3.1.3.3. Logging data quality

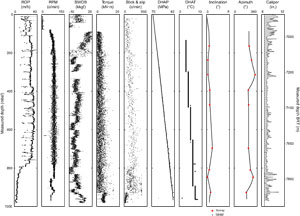

Three elements are used to assess the borehole quality of the LWD data: (1) borehole conditions, (2) comparison between logs done in the same interval, and (3) consistency of the measured sonic and electrical logging data with QC information provided by the contractor.

3.1.3.3.1. Borehole conditions and drilling parameters

Figure F7 shows an overview of the Hole C0019H QC with drilling parameters and frequency of stick-slip. The logs indicate that the borehole was drilled relatively smoothly. However, stick-slip behavior of the drill bit occurred in various intervals, which influenced the quality of the image logs. Large sections of the real-time image logs were not transmitted because of the stick-slip of the BHA. These intervals were later recovered in the memory data. Horizontal image artifacts are common throughout the entire imaged interval and are thought to be related mainly to the stick-slip of the MicroScope tool as the buttons rotate (Lofts and Bourke, 1999).

The ROP was reduced from an average of 40–50 m/h to around 15 m/h around 793 mbsf to mitigate stick-slip, resulting in improved quality of image logs below this depth. The overall quality of the image data above 793 mbsf is variable, where depths with high stick-slip have lower image quality and increased artifacts (e.g., 460–480 and 522–536 mbsf). The overall quality of the image data below 793 mbsf is very good, with ~99% of the logged section imaged.

The real-time borehole survey is the basis for the borehole orientation data. Hole C0019H was drilled with the spare TeleScope tool and tended to have more variable orientation records compared to Hole C0019F, which was drilled with the primary TeleScope tool. Few reliable survey points were obtained, and the orientation of the borehole was linearly interpolated between these points (Figure F7). The borehole stays vertical with a maximal inclination of 1.25° at 696 mbsf. Borehole images are reoriented using the borehole surveys provided by the Telescope (inclination and azimuth). Geographic reorientation of structural features is further discussed in Resistivity image interpretation.

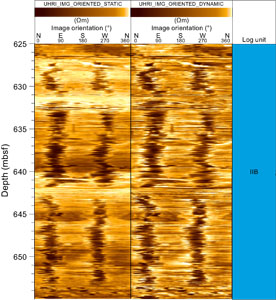

3.1.3.3.2. Comparison of main and relogged sections

The interval from 646 to 846 mbsf was logged a second time during pipe retrieval to ensure that a full suite of image logs was acquired over this interval and to observe the evolution of the borehole conditions over time. Five resistivity logs (shallow, medium, deep, extra deep, and UHRI) were collected during relogging. The Logging Staff Scientist adjusted the depths of the relogged data by correlating variations in the gamma ray log with the main run.

The relogged data show similar deep resistivities to the main run, but shallow resistivities are lower during the relog, which suggests enlargement of the borehole between 740 and 825 mbsf. The poorer quality of the image logs for this second logging run indicates that borehole conditions degraded between the runs (Figure F8). This negatively affected the quality of the repeat resistivity images, which exhibit lower electrical resistivities recorded on the damaged side. Gamma ray is also lower at the location of the borehole enlargement.

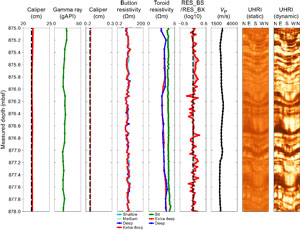

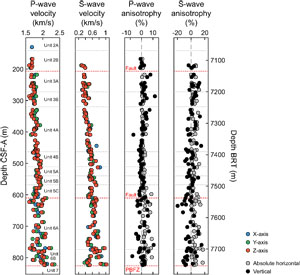

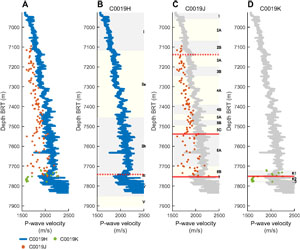

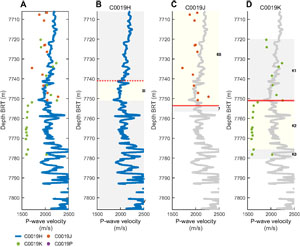

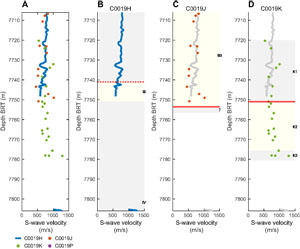

3.1.3.3.3. Consistency of sonic logging data

SLB provided a composite P-wave log by merging the velocity determined from Leaky P analysis to 920 mbsf and P-wave analysis to total depth (Figure F9). For Leaky P, the reference QC curve is the slowness-frequency analysis (SFA) obtained from dispersion analysis of the low-frequency band of the monopole waveforms; the picked slowness should lie on the left edge of the SFA projection (Plona et al., 2006). For the P-wave analysis, the reference QC curve is the slowness-time projection (SPR) for the high-frequency band of the monopole waveforms; the picked slowness should lie at the maximum of this projected coherence log. There is no interval where both analyses were conducted simultaneously.

Figure F9 summarizes the QC plots provided by SLB. Above 825 mbsf, the SFA intensity is strong and the picked P-wave slowness is reliable. The SFA intensity becomes much weaker below 825 mbsf and vanishes at 920 mbsf. The P-wave velocities estimated with the Leaky P method are therefore much noisier, but the picked slowness is consistent with the coherence plot. The picked estimate is likely to be reliable between 825 and 920 mbsf. Although the SPR plot of the high-frequency monopole waveform is strong in this interval, SLB chose not to use this to better constrain the P-wave velocity estimate and instead used only the Leaky P method.

Below 920 mbsf, P-wave velocities are picked from the high-frequency monopole data. The coherence on which the P-wave slowness is picked seems weak, but this may be biased by another strong coherent phase in the waveform. Direct observation of the waveforms provides additional insight on the quality of the picking (Figures F10, F11). Below 925 mbsf, the P-wave velocities are large enough for the arrival times to coincide with those of the collar wave. In two intervals (920–925 and 931.5–938 mbsf) the sonic signal is strongly attenuated. However, high P-wave velocities were estimated at those intervals, possibly due to incorrect picking of the collar wave arrivals. Accordingly, P-wave velocities should be treated as unreliable in these two intervals.

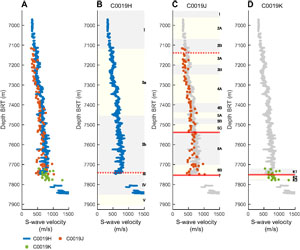

The reference QC plot for the quadrupole signal is the SFA plot (Figure F9). The signal-to-noise ratio of S-wave velocity (VS) is often very low. No VS could be picked between 825 and 925 mbsf. In their processing report, SLB stated that VS data may be unreliable for depths shallower than 200 mbsf. However, the arguments listed below suggest that VS data should also be unreliable in other intervals of the borehole. Firstly, large nonrealistic VP/VS ratios (>4) are observed in the shallow part of the hole. These values coincide with the lower intensity slowness-frequency projection for the quadrupole signal. Also, the picked velocity tends not to align with the left part of the SFA plot, suggesting lower slowness and hence higher shear-wave velocity than measured. Finally, Figure F10 shows that the quadrupole waveforms are dominated by high-frequency oscillations that are much larger than the target bandwidth of 1–1.5 kHz (Figure F11). After bandpass filtering, screw waves can be tracked along the receivers for the depths between 300 and 825 mbsf (e.g., at 502 mbsf) at times earlier than the picked arrival time. A further in-depth analysis of the sonic data might provide more reliable velocities. For the current data set, VS values shallower than 350 mbsf should be considered with great care.

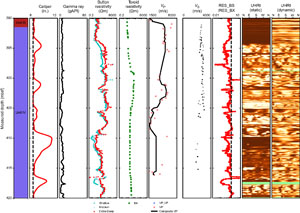

3.1.3.3.4. Consistency of electrical logging data

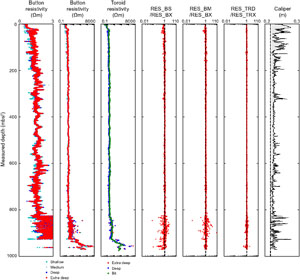

A qualitative QC criterion is the agreement between the different resistivity channels (at different depths of investigation). Except for shallow resistivity, the button resistivity channels are consistent for most of the borehole. However, the bit resistivity is smoother and higher than the other toroid resistivity channels (Figures F12, F13, F14). This could be attributed to the following:

- A change in the BHA compared to the planned BHA for Hole C0019H set prior to the expedition, which would change the geometrical factor used to compute the bit resistivity (see Logging while drilling in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025]);

- Potential electromagnetic interference with the downhole motor; and/or

- A scale effect associated with the difference in depth of investigation between the bit and button resistivity measurements (see Logging while drilling in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025]).

3.1.3.4. Issues encountered in logging data

The quality of the LWD data is generally good, but some care is needed when using this data set:

- Bit resistivity data are systematically offset from the other resistivity logs (see above).

- The borehole directional survey data (inclination and azimuth) initially showed spikes and some unrealistic jumps that were filtered and smoothed in the final dataset.

- Sonic velocities must be considered with great care. P-wave velocities between 920 and 925 mbsf and between 931.5 and 938 mbsf are to be discarded. S-wave velocities are unreliable in the uppermost interval to 300 mbsf because of the low intensity of the quadrupole signal and the unrealistically large VP/VS values (>4) implied by the picked estimate.

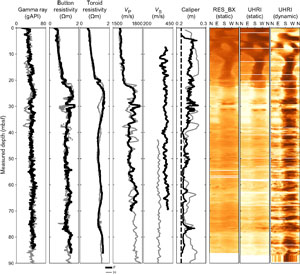

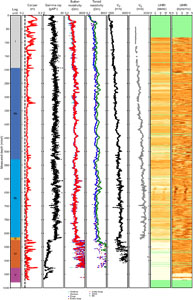

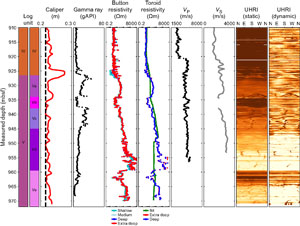

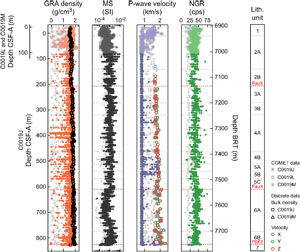

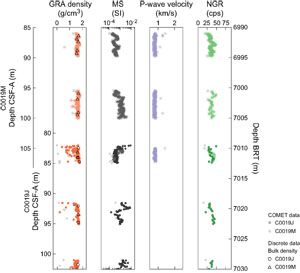

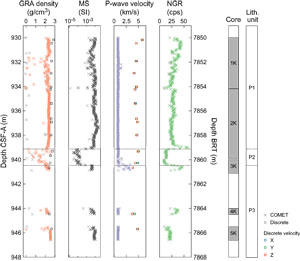

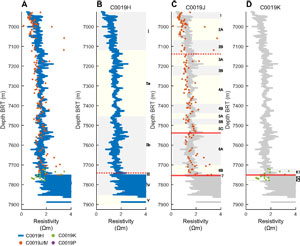

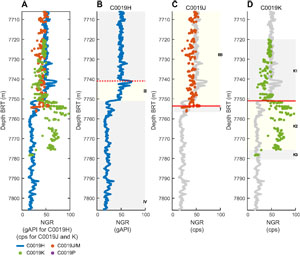

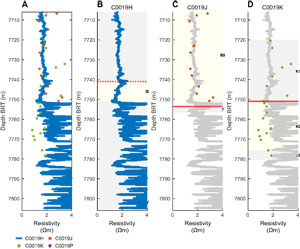

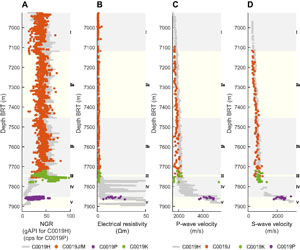

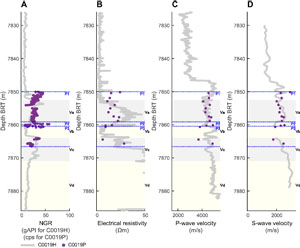

3.2. Logging units

Using a combination of different LWD measurements, particularly gamma ray, resistivity, and sonic logs, we defined five logging units (I–V) (Figures F12, F13). Because Holes C0019F and C0019H were drilled in close proximity (~30 m separation) and show similar variations in their physical properties (Figure F5), logging units for those holes were combined. These holes are also in close proximity to previously drilled Expedition 343 Hole C0019B (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013b) and Site C0026 drilled during this expedition (see Lithostratigraphy in the Site C0026 chapter [Conin et al., 2025]). Logging units from Hole C0019B were taken as reference to facilitate comparison between all Site C0019 holes.

3.2.1. Logging Unit I (0–193.5 mbsf)

Logging Unit I is characterized by moderate gamma ray values ranging ~20–50 American Petroleum Institute gamma radiation units (gAPI) (average = 41 gAPI), very low resistivity (typically 0.5–1.8 Ωm), and low P-wave velocity (VP) values (~1550–1750 m/s), with both P-wave velocity and resistivity values increasing slightly with depth (Figure F13). This is consistent with a burial compaction trend for shallow unconsolidated sediments. Based on these log characteristics and lithologic description from Hole C0019J (see Lithostratigraphy), this unit likely consists of poorly compacted siliceous mudstone. The uppermost ~20–30 m interval has very low P-wave velocity, gamma ray, and resistivity values (Figure F5), likely caused by poor borehole conditions, evident from the borehole image logs.

3.2.2. Logging Unit II (193.5–815 mbsf)

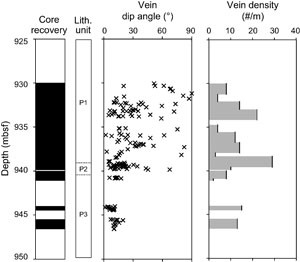

Logging Subunit IIa (193.5–528.6 mbsf) is defined as an interval of slightly higher gamma ray, resistivity, and P-wave velocity values compared to the unit above. The top of the unit is defined at a sharp gamma ray peak at 193.5 mbsf, below which gamma ray values range ~40–60 gAPI with an average value of ~50 gAPI. Resistivity values are typically ~1.2–3 Ωm, and P-wave velocity is typically 1900 m/s. Gamma ray, resistivity, and P-wave velocity are relatively consistent with only minor excursions from this range, suggesting that the lithology is similar throughout. Borehole images show several 1–10 m thick resistive intervals not correlated with the e-caliper log but correlated with slightly higher gamma ray values, indicating subtle compositional differences. Borehole breakouts are observed between 310 and 410 mbsf; however, they are of lower quality than the breakouts that reappear in Subunit IIb (Figure F15). The lower section of this logging unit (~479–528.6 mbsf) is characterized by higher gamma ray and resistivity values.

Subunit IIb (528.6–815 mbsf) is defined at the top by an abrupt decrease in gamma ray values from 70 to 40 gAPI at 528.6 mbsf and generally lower gamma ray and resistivity values compared to Subunit IIa. Gamma ray values generally range 40–60 gAPI, and resistivity values generally increase slightly with depth. Borehole breakouts are clearly resolved between 570 and 670 mbsf and become less common at the base of Subunit IIb (Figure F15).

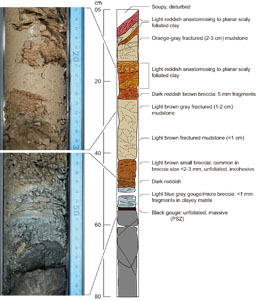

3.2.3. Logging Unit III (815–825 mbsf)

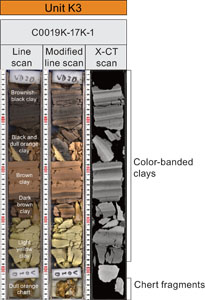

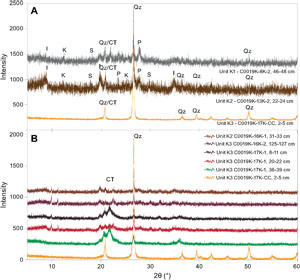

Logging Unit III is characterized by high gamma ray values of up to 72 gAPI in a few meters thick interval at the top of the unit that is interpreted to correspond to clays. Beneath this interval is an interval of slightly lower gamma ray values similar to those in Subunit IIb. This interval is also marked by a gradual downhole decrease in resistivity from ~2 to 1 Ωm and a decrease in P-wave velocity. Overall, this pattern presents similarities with units recovered in Cores 343-C0019E-17R through 20R, in which a sheared clay lithology was underlain by mudstone and banded clay and chert (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013b; Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980).

3.2.4. Logging Unit IV (825–926.5 mbsf)

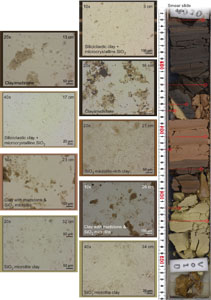

The top of Logging Unit IV is characterized by a sharp decrease in gamma ray values and a significant increase in resistivity. Gamma ray values for this unit are consistently lower than in the units above, with a typical range of 10–20 gAPI and an average of 16.56 gAPI. Gamma ray log values show a decreasing trend with depth from an average value of around 20 gAPI to consistently less than 10 gAPI near the base of the unit. Resistivity values increase from 1.34 Ωm at the top of the unit to 6.52 Ωm at the base of the unit. Borehole images show alternating layers of lower and higher resistivity (Figure F16). This interval caused significant drilling issues with persistent stick-slip behavior. Only the upper ~15 m of this sequence was drilled this site during Expedition 343/343T, but based on Expedition 343 (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013b), DSDP Site 436 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980), the Site C0019 log responses described here, and cores from Holes C0019J, C0019K, and C0026B (see Lithostratigraphy), this sequence likely consists of chert, possibly interbedded with other sedimentary rocks.

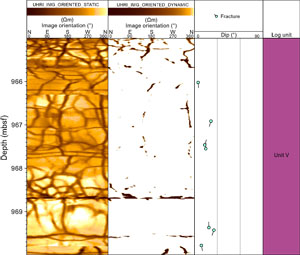

3.2.5. Logging Unit V (926.5–980 mbsf)

The top of Logging Unit V is characterized by an abrupt increase in gamma ray values, resistivity, and P-wave velocity at 926.5 mbsf (Figure F17). These logs exhibit significant variation in this unit that can be used to define five distinct subunits. This unit has not been previously drilled elsewhere in this region.

Subunit Va (926.5–934 mbsf) is characterized by high gamma ray values with a peak at 55 gAPI, which then decline to 20–30 gAPI at the base of the subunit. Both resistivity and P-wave velocity are relatively high, up to 40 Ωm and an average of 4402 m/s, respectively. Resistivity image logs show distinctive nonplanar resistive bands that indicate curved surfaces with varying dip angles and azimuths. Although there are no drilled analogs in the region, the log character is consistent with basalt or mixed basalt and sedimentary rocks.

Subunit Vb (934–938 mbsf) is characterized by relatively low gamma ray (~5 gAPI) and moderate resistivity values similar to those in Unit IV. P-wave velocities are unreliable in this interval (see Logging data quality in Hole C0019H). Borehole image logs show alternating high and lower resistive bands with a ~50 cm spacing, again similar to those observed in Unit IV. This suggests the presence of chert or similar siliceous sedimentary rocks.

Subunit Vc (938–945 mbsf) is characterized by moderately high gamma ray values between 30 and 45 gAPI and moderately high resistivity increasing downhole from 30 to 300 Ωm. Borehole images show nonplanar features of contrasting resistivity similar to those in Subunit Va. These appear lenticular in the wraparound image logs, indicating curved surfaces. The log character is consistent with basalt or mixed basalt and sedimentary rocks.

Subunit Vd (945–959.5 mbsf) is characterized by low gamma ray values ranging 5–10 gAPI. Resistivity values are high throughout, ranging 80–300 Ωm near the top of the sequence. This increases gradually to 955 mbsf, below which resistivity values become very high, up to 8000 Ωm. This lower interval shows significant separation between the shallow and extra deep resistivity, with the shallow resistivity typically around half of the extra deep values. Borehole images show low-angle bands of alternating resistivity to ~657 mbsf and a massive high resistivity unit with spiraling near-vertical conductive features that may be consistent with fractures.

Subunit Ve (959.5–980 mbsf) is characterized by moderate gamma ray values at the top of up to 50 gAPI, decreasing to less than 5 gAPI at the base of the unit at 969 mbsf. Resistivity increases from ~3–80 gAPI at the top of the section to ~500 Ωm at the base of the section. Borehole images show nonlinear alternating resistivity bands and near-vertical conductive features.

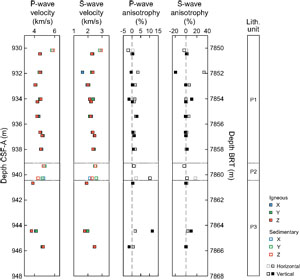

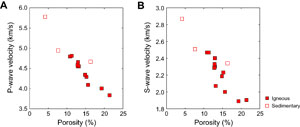

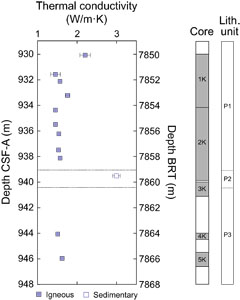

3.3. Physical properties

The LWD data provide information on the natural radioactivity (gamma ray), electrical resistivity (button and toroid velocities), and sonic velocities for both P- and S-waves.

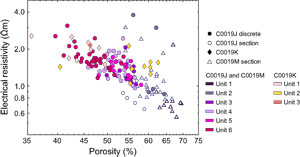

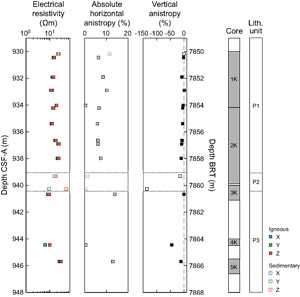

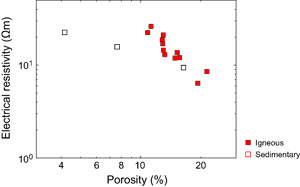

3.3.1. Electrical resistivity

The four channels of button resistivity (shallow, medium, deep, and extra deep) are also provided as 360° borehole images, but only scalar channels (RES_BS, RES_BM, RES_BD, and RES_BX) will be discussed here. These channels have different depths of investigation (see Logging while drilling in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025]) to discriminate the true resistivity of the rock from the effects of borehole mud and an eventual invaded zone. Because borehole mud has lower resistivity (0.11 Ωm) than the formation, borehole enlargement induces a decrease in the measured resistivities, especially for the shallowest channels. This effect is used to infer the e-caliper from the resistivity measurements (Channel HD_MI6). Hence, this caliper is included with the other electrical channels in Figure F18.

Figures F14 and F18 show good agreement between the electrical logs, except for Units IV and V, so the deep resistivities can be considered representative of the true formation resistivity. These units have strong excursions of the ratio RES_BS/RES_BX to low values, which in Unit IV is consistent with an increase in borehole diameter. In Unit IV, several depths exhibit shallow resistivity larger than deep resistivity (Figure F16) that cannot be explained by borehole enlargement, which would decrease shallow resistivity more strongly than deep resistivity. The ratio between medium and extra deep resistivity also exceeds 1 at those depths, suggesting this is related to the formation rather than borehole diameter. Because Unit IV is interpreted to be chert, which is strongly banded, this effect may be due to the strong formation anisotropy.

Given the good agreement between the deep resistivity logs, these resistivities are considered to be representative of the true formation resistivity. Between these, the extra deep resistivity (RES_BX) was chosen as a reference log because of its higher sampling rate (see Table T3 in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025]).

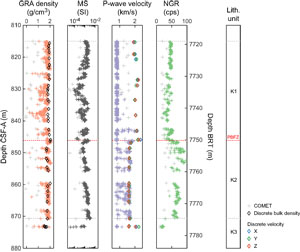

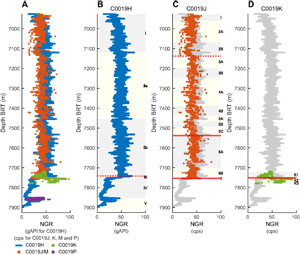

3.3.2. Statistics of physical properties

Figure F19 shows the statistical properties of the major physical properties for each logging unit (given their extent, Subunits IIa and IIb are considered separately), for which the mean and standard deviation are reported below. Hole C0019H shows strong petrophysical contrasts between the logging units.

Gamma ray is 41 ± 7 gAPI in Unit I and increases to 48 ± 6 gAPI in Subunit IIa. Subunit IIb and Unit III have similar values, 49 ± 7 and 51 ± 8 gAPI, respectively. Gamma ray decreases in Units IV and V, to 16 ± 7 and 17 ± 9 gAPI, respectively.

Electric resistivity in Figure F19 is on a logarithmic scale to capture the full extent of variation: the quantity log10(RES_BX) was used to generate the box plot. In the following paragraph, the measured values (RES_BX) are used instead to compute the statistics. In Unit I, extra deep resistivity is 1.23 ± 0.23 Ωm. It increases to 1.59 ± 0.20 Ωm in Subunit IIa. Subunit IIb and Unit III have similar values, 1.58 ± 0.16 and 1.64 ± 0.22 Ωm, respectively. The mean resistivity in Unit IV increases to 4.3 Ωm with an interquartile extent of 1.4 Ωm, reflecting the large variability within this unit. In Unit V, the mean value of the electrical resistivity reaches 379 Ωm, but its median is 59 Ωm. This reflects the large variability in this unit, in which the resistivity varies between 2 Ωm and 20 kΩm.

P-wave velocity is 1730 ± 70 m/s in Unit I. It increases from Unit I to Unit II, and it also increases between Subunits IIa and IIb, to 1940 ± 80 and 2110 ± 70 m/s, respectively. Velocity decreases to 1990 ± 60 m/s in Unit III. P-wave velocity strongly increases to 2540 ± 650 m/s in Unit IV. In Unit V, very high P-wave velocities with values of 4710 ± 320 m/s were measured.

Units I–III are similar, in sharp contrast to Units IV and V.

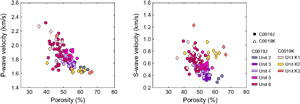

3.3.3. Relations between physical properties

Figure F20 shows crossplots between the main physical properties (gamma ray, P-wave velocity, and electrical resistivity) as well as the Brie plot to interpret the relationship between P- and S-wave velocities. This plot is a graphical representation used to identify zones of free gas in sedimentary rocks (Brie et al., 1995). It is based on the crossplot between 1/V and VP/VS that represents a convenient method to compare VP and VS data.

Figure F20A compares electrical resistivity to gamma ray. In this crossplot, the points represent the Unit I transition from a cluster of low resistivity corresponding to the uppermost 25 m of Hole C0019H to values close to those of Unit II (Figure F5). Subunits IIa and IIb and Unit III overlap. Unit IV is distinctive in its lower gamma ray values, and Unit V is distinctive in its higher resistivity values (except for Subunit Vb, which overlaps with Unit IV).

The crossplot between P-wave velocity and gamma ray (Figure F20C) is similar, with Units I–III clustering at high gamma ray and low resistivity values and the Unit IV and V data points gathering in two independent low and high velocity clusters, respectively. The data points of Unit IV at high velocity correspond to the erroneous intervals identified in the QC and should be considered unreliable. The Subunit Vb data points should be also considered with great care. In Unit IV, there is a negative correlation between gamma ray and P-wave velocity.

Figure F20D shows a positive correlation between resistivity and P-wave velocity, which is particularly well defined for Units I–III. A positive but more scattered correlation is also observed in Unit IV if the erroneously high VP between 920 and 925 mbsf are not taken into account. Unit V is characterized as a high velocity zone (but the VP of low resistivity zones were not measured).

In Figure F20B the high VP/VS values recorded in Hole C0019H correspond to very large Poisson ratios, which prevent comparison with reference curves. Despite the high value of VP/VS, the Unit I–III data points align along a typical convex shape. Unit IV is in continuity with this trend, with wide scatter. There is no significant excursion away from this trend toward the region of high 1/V and low VP/VS that would indicate in situ free gas (Brie et al., 1995). Unit V data form an isolated cluster of lower 1/V and VP/VS ranging 1.7–2.5.

3.3.4. Resistivity image interpretation

The overall image quality is good for Hole C0019H. Geologic features (bedding and fractures) as well as wellbore failures (breakouts) were identified from the images. Horizontal image artifacts are common throughout the entire imaged interval and are thought to be related to the stick-slip of the MicroScope tool as the buttons rotate (Lofts and Bourke, 1999). All images were oriented to north using the orientation information from the TeleScope (Figure F7), and the inclination of the hole was accounted for. Geologic features are identified and characterized with the true orientation reported.

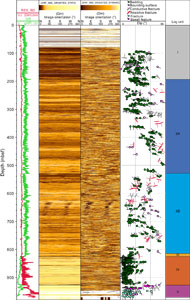

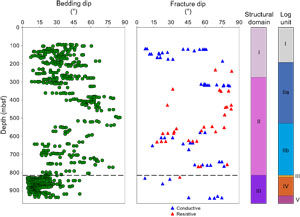

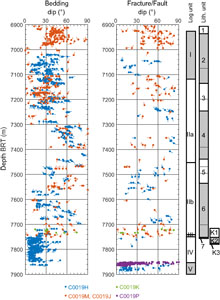

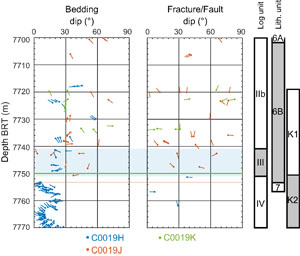

3.3.5. Bedding and fractures

Structural and sedimentary features are identified and interpreted using the UHRIs (Figures F21, F22). Critical examination of each pick was made by three simultaneous observers to confirm (1) clear sinusoidal curves on the unwrapped images of the cylindrical borehole wall and (2) consistent criteria for structural and bedding interpretation. The image data contain various artifacts (Lofts and Bourke, 1999), including horizontal stripes caused by ship heave, processing, and stick-slip of the tool, and some vertical conductive stripes indicative of tool scraping were observed locally, making image interpretation challenging. Planar features in the logs were divided into five categories. The criteria are as follows:

- Bedding: a planar feature, visible as a sinusoid in the unwrapped static and dynamic UHRIs, that belongs to a series of planar features with consistent orientation (Figure F23). Bedding planes are reported in Table T6.

- Conductive/resistive fracture: a planar feature, visible as a sinusoid in the flattened image, that may or may not host shear displacement. The orientation crosscuts the orientation of nearby bedding. We note whether the fracture is predominantly resistive or conductive (Figure F24). Conductive and resistive fractures are reported in Tables T7 and T8, respectively.

- Bounding surface/feature: when a crosscutting relationship is not evident but a planar discontinuity or distinctive change in resistivity (i.e., more conductive to less conductive across a sinusoidal feature) is clear, we note the feature as a bounding surface. This may be indicative of a change in bulk rock properties or a fault/fracture along a plane of weakness aligned with nearby bedding. Bounding surfaces are reported in Table T9.

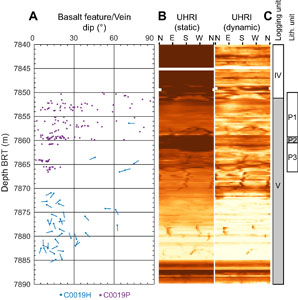

- Basalt feature: conductive bands in Unit V, interpreted to be basalt, with consistent orientation and spacing of ~10–20 cm (Figure F24B). Bands are crosscut and disrupted by other features in the unit that may be associated with emplacement or later stage deformation and fracturing. Basalt features are reported in Table T10.

- Fracture in basalt: dark features in Unit V (Figure F25). These fractures may be indicative of contacts between basalt and other sediments, cooling fractures, boundaries between lava flows, or related to late-stage deformation and fracturing. Fractures are reported in Table T11.

Differentiation between fractures and bedding planes is complex in regions of high deformation, and we acknowledge that some features may have been misclassified during the shipboard analysis. Additionally, faults and fractures can form along weakened bedding planes, and we are unable to distinguish between slip surfaces and bedding when there is no crosscutting relationship.

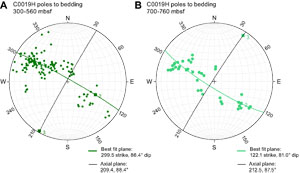

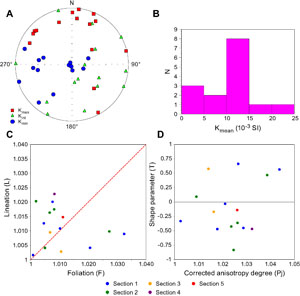

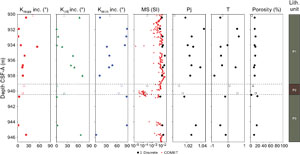

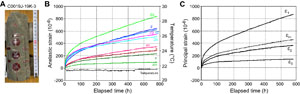

Three structural domains are defined based on bedding orientations: Domain 1 (0–275 mbsf), Domain 2 (275–815 mbsf), and Domain 3 (815–980 mbsf) (Figure F22). Domain 1 features 20–80 m thick packages of bedding that alternate between eastward and westward dips, with a high concentration of conductive fractures observed between 100 and 200 mbsf. The average bedding dip in this domain is moderate at approximately 30° ± 12°. Domain 2 displays a wider range of bedding dips from 8° to 85°, with an interval of steeply dipping bedding between 400 and 600 mbsf. On a stereographic projection, the poles to bedding between 300 and 560 mbsf and between 700 and 760 mbsf have girdle distributions indicative of cylindrical folding (Figure F26). The section between 550 and 670 mbsf is densely fractured and may be part of a fold limb or a different structural package. Below 815 mbsf, a sharp transition to shallowly dipping bedding, averaging 15° ± 8°, marks the onset of Domain 3.

The bounding surfaces identified in Hole C0019H are detailed in Table T9. These structures may indicate fractures formed along weakened bedding planes or represent a change in bulk rock properties. However, we did not classify these features as either bedding or fractures because no crosscutting relationships with adjacent bedding planes were observed.

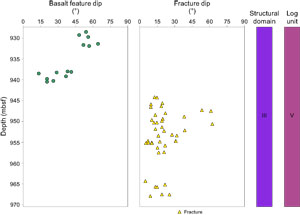

The UHRIs in Unit V show rounded to subrounded features consistent with basalt (Ienaga et al., 2006; Fornero et al., 2019) (Figure F25). Evenly spaced conductive bands are interpreted to be basalt features that could correspond to emplacement or tectonic deformation (Figure F24B). These features are moderately dipping (~48°–65°) in Subunit Va and shallowly dipping (~13°–40°) in Subunit Vc (Figure F27. Other features, possibly fractures, crosscut and offset the orientation of these basalt features. Subunits Ve and Vd exhibit a dense network of shallow conductive fractures that are highly deformed (Figure F25). These fractures may have originated during the deposition and cooling of the basalt or as a result of later tectonic activity.

3.3.6. Wellbore failure

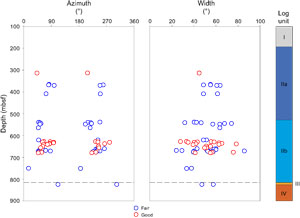

In Hole C0019H, LWD images show dark conductive tracks approximately 180° apart that are consistent with borehole breakouts (Figure F15) (Gough and Bell, 1981; Bell and Gough, 1982; Zoback, 2007). Breakouts occur between 312 and 824 mbsf but are concentrated within Unit III in two intervals: 530–570 and 615–680 mbsf (Figure F28). Variable image quality and ambiguous artifacts in the images result in uncertain breakout picks in some depth intervals (e.g., 310–410 mbsf). Quality codes of “good” and “fair” are assigned to the breakout picks. Good breakouts are identified by two continuous conductive tracks 180° apart that are identifiable in both the UHRIs and lower resolution images. In addition, good quality breakouts are located at depths free from known drilling-related artifacts (i.e., horizontal stick-slip, stretching, or plausible damage from the tool scraping). The quality code fair is used when breakouts are identified at depths with image artifacts or when the conductive tracks are not continuous.

A total of 61 breakouts were identified in the images, of which 23 breakouts were good and 38 breakouts were fair (Figure F28; Table T12). The cumulative length of breakouts reached ~100 m, corresponding to ~10% of the total borehole depth. The mean breakout orientation is 062° (or 242°) with a standard deviation of 22°. The orientation of maximum horizontal stress (SHmax) is interpreted to be 152° ± 22°. The breakout azimuths near the interpreted plate boundary fault at ~823 mbsf are rotated approximately 50°–60° to the east-southeast from the breakouts in the overlying prism. Breakout widths range 24°–86° with a mean value of 51° (±13° standard deviation).

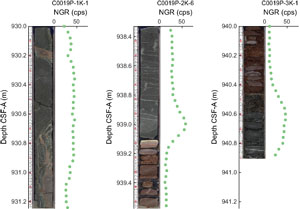

4. Lithostratigraphy

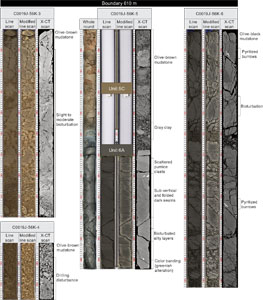

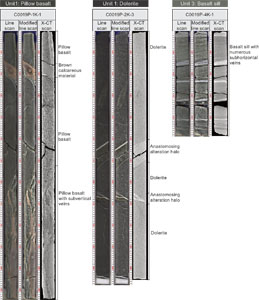

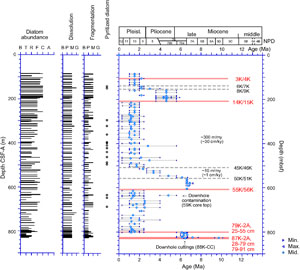

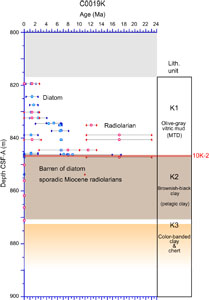

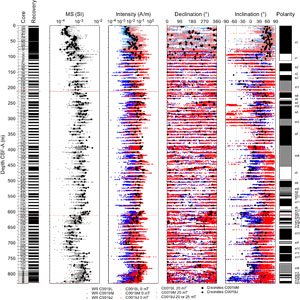

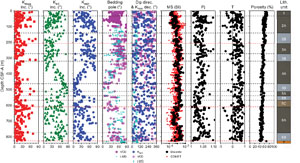

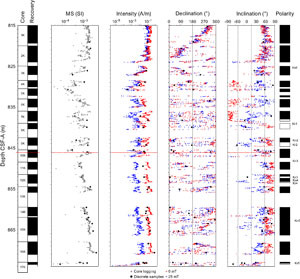

We report here on the lithostratigraphy of the five holes at Site C0019. Cores from Holes C0019L, C0019M, and C0019J were collected in close proximity (Figure F1) and represent a complete depth transect through the frontal prism to the décollement and are therefore presented together. Holes C0019K and C0019P were located farther apart and represent different depths beyond the décollement into the lower plate. The lithologies for these holes are therefore presented separately and are ascribed unit prefixes K (Hole C0019K) and P (Hole C0019P).

4.1. Lithostratigraphic units of Holes C0019L, C0019M, and C0019J

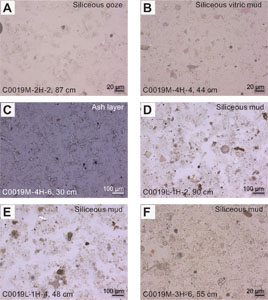

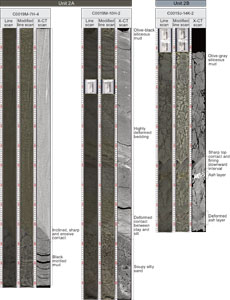

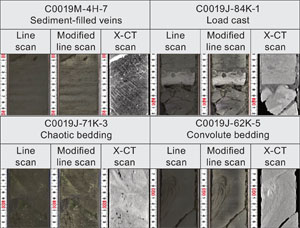

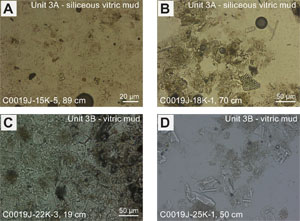

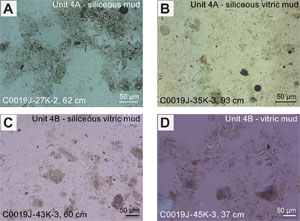

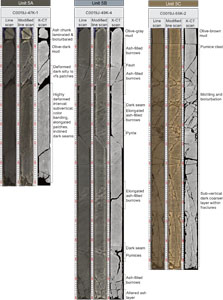

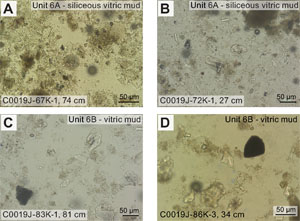

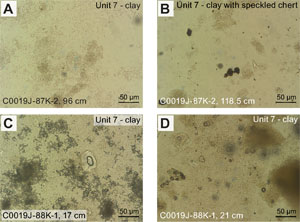

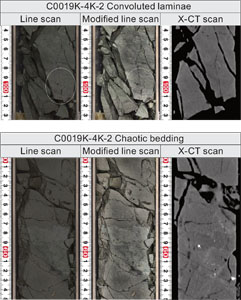

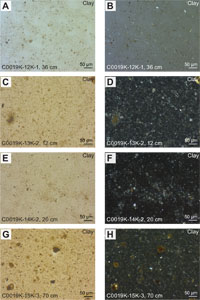

Seven lithostratigraphic units were identified in the composite stratigraphy from Holes C0019L, C0019M, and C0019J, and all lithostratigraphic units are present in Hole C0019J (Figure F29). The units are numbered from 1 to 7 sequentially with depth from the seafloor to the base of the cored interval (Table T13) (for differentiation methods, see Lithostratigraphy in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025]). Units 2–6 are divided into subunits labeled A, B, and C from top to bottom. Units 2–6 contain a similar lithologic sequence: Subunit A is olive-black siliceous vitric mud(stone), Subunit B is olive-gray to gray siliceous vitric mud(stone), and Subunit C (only present in Unit 5) is dull yellowish brown siliceous vitric mud(stone).

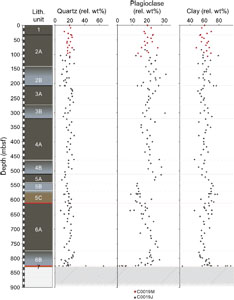

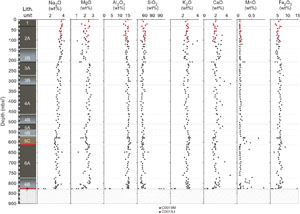

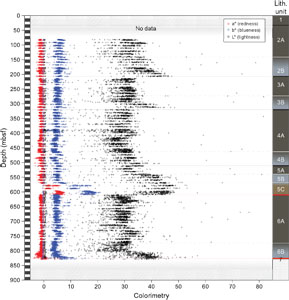

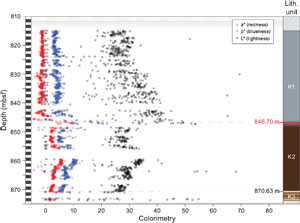

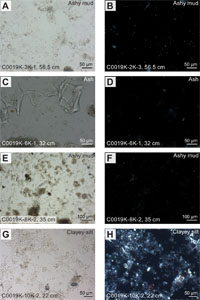

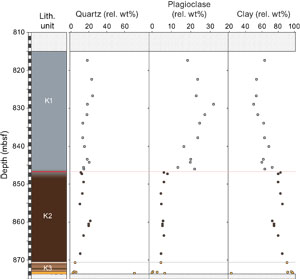

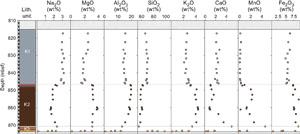

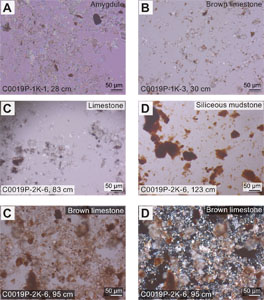

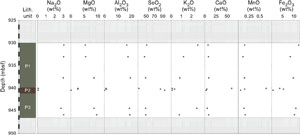

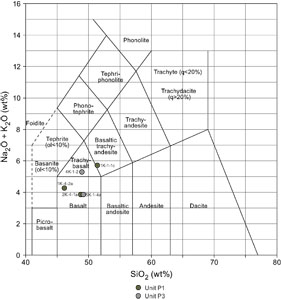

Representative intervals of each unit and the unit boundaries are illustrated by Tri-Sensor Core Logger (TSCL) linescan images, modified linescan images, and X-ray computed tomography (XCT) images (Figures F30, F36, F39, F40, F42, F44, F46, F47, F49). Additional notable features in the cores, alongside corresponding TSCL images, are recorded on the visual core descriptions (VCDs) in Core descriptions. Semiquantitative sediment compositions derived from smear slides are summarized in ternary diagrams (Figures F31, F32), and key classifications are displayed in selected microscopic images (Figures F33, F37, F41, F43, F45, F48, F50). The grain size and compositional ranges presented for each unit and subunit discussed below and in Tables T14 and T18 report the range between the lowest (L) recorded and highest (H) recorded percent of each grain size fraction (displayed as L%–H%). It is noted that, because smear slide analysis is semiquantitative, further grain size distribution analysis is needed. Core colorimetry data from the TSCL provided important information on color variations across the units in Hole C0019J (Figure F38). TSCL colorimetry data are not available for Holes C0019L and C0019M due to equipment malfunction during coring operations. Variations in bulk composition throughout the holes are documented using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis for mineral phases and abundance (Figure F34; Table T15) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis for elemental composition (Figure F35; Table T16). Age estimates for each unit are provided from preliminary shipboard biostratigraphy (see Biostratigraphy).

Unit depths are calculated on the core depth below seafloor scale, Method A (CSF-A), but are listed as mbsf depths here.

4.1.1. Unit 1

- Interval: 405-C0019L/M-1H-1, 0 cm, to 405-C0019M-5H-1, 0 cm

- Depth: 0–33.00 mbsf

- Age: 0–? (2.7) Ma

- Lithology: olive-black siliceous vitric mud

4.1.1.1. Visual core description lithology

Unit 1 is present in Hole C0019L from 0 to 5.38 mbsf and in Hole C0019M from 0 to 33.00 mbsf (Figure F29; Table T13). Unit 1 is an olive-black to gray (7.5Y 3/1, 5Y 3/1, and 10Y 4/2) siliceous vitric mud with frequent intervals of chaotic and inclined bedding interspersed with clasts and occasional layers of ash (occasionally deformed) and graded bedding (Figure F30). Unit 1 contains large rip-up clasts of variable color composed of a lithology similar to, but more indurated than, the background sedimentation. Color banding (millimeter-scale and usually highlighted by bands of black and green) is frequent throughout Unit 1, often parallel with interbedded ash. Sometimes these color bands delineate folding and deformation (e.g., Section 405-C0019M-4H-4). Fining-upward sand layers (sometimes with multiple pulses) occur infrequently throughout Unit 1 (e.g., Section 405-C0019L-1H-3). There is evidence of sediment remobilization and liquefaction; for example, a sand-hosted mud-injectite sourced from underlying mud intruding into a small-scale reverse fault (Section 405-C0019M-4H-5, 110–112 cm). Unit 1 also contains moderate bioturbation, areas rich in pyritization, and calcite concretions.

A total of 15 ash horizons were identified in Unit 1 either as laterally continuous layers with thicknesses from <1 cm to several centimeters thick or as subrounded patches (e.g., Section 405-C0019M-4H-6). Where bedding is distinguishable, ash layers commonly have sharp contacts with the background sedimentation. Both the ash layers and bedded background sedimentation are mostly inclined (e.g., Section 405-C0019L-1H-3; Figure F30) (see Structural geology). The continuous laminated ash layers tend to be dark green-gray in color, whereas the patches can also be light gray and blue (e.g., Section 405-C0019M-2H-3). Pumice pieces disseminated throughout the background sedimentation are occasionally present and sometimes pyritized (e.g., Sections 3H-6, 77 cm, and 5H-1, 56 cm).

4.1.1.2. Smear slide petrography

The grain size of the background sedimentation in Unit 1 predominately plots as mud (Figure F31) with 0%–30% sand, 25%–92% silt, and 5%–75% clay (Table T14), and the composition predominantly plots as siliceous to siliceous-vitric mud (Figure F32) with 8%–68% siliciclastic, 2%–46% volcanic, and 6%–72% biogenic grains. The siliciclastic material is predominantly clay minerals (2%–60%), quartz (0%–31%), and mudstone aggregates (0%–20%). Volcanic material is mostly clear glass (1%–37%) and pumice (0%–20%) with some colored glass (0%–10%). Biogenic material is mostly diatoms (2%–32%), radiolarians (0%–15%), silicoflagellates (0%–10%), and sponge spicules (2%–38%) (Figure F33). The remainder of the material (2%–35%) includes pyrite framboids, glauconite, micas, and opaque and dense minerals.

The occasional ash layers are generally coarser, plotting as silty sand to silt (Figure F31) with 9%–58% sand, 40%–81% silt, and 2%–10% clay. They are compositionally volcanic with siliciclastic (5%–6%), volcanic (76%–81%), and biogenic (0%–9%) material (Table T14).

4.1.1.3. Mineralogy and sediment geochemistry

A total of five bulk samples representative of Unit 1 were analyzed for XRD. Clay mineral content dominates the composition (55–69 wt%), with lesser amounts of quartz (13–21 wt%) and plagioclase (18–24 wt%) (Figure F34; Table T15). The variability in the relative abundances of clay, quartz, and feldspar is consistent with the observed differences in the VCDs and smear slides. XRF and loss on ignition (LOI) analyses on the same samples yield the following elemental abundances (Figure F35; Table T16): 3.67–3.79 wt% Na2O, 1.61–2.55 wt% MgO, 12.45–15.22 wt% Al2O3, 66.23–72.84 wt% SiO2, 0.09–0.12 wt% P2O5, 2.41–2.67 wt% K2O, 1.62–2.35 wt% CaO, 0.44–0.68 wt% TiO2, 0.06–0.07 wt% MnO, 3.97–6.29 wt% Fe2O3, and 6.51–7.74 wt% LOI. The concentration of SiO2 is consistent with the relatively high proportions of volcanic glass and siliceous biogenic components in this unit.

4.1.1.4. Summary and preliminary interpretation

Unit 1 consists of olive-black siliceous vitric mud with 15 interspersed ash horizons. This unit is characterized by inclined bedding with frequent fining-upward layers. In contrast to typical seafloor sediments, the uppermost sediments of Unit 1 are already semiconsolidated. These properties, alongside the chaotic and inclined bedding, are consistent with deposition from mass transport processes (i.e., mass transport deposit) originating from a landward position in a shallower section of the trench slope.

4.1.2. Unit 2

4.1.2.1. Subunit 2A

- Interval: 405-C0019M-5H-1, 0 cm, to 405-C0019J-7K-2, 0 cm

- Depth: 33.00–141.24 mbsf

- Age: 0–2.7 Ma

- Lithology: olive-black siliceous vitric mud(stone)

4.1.2.1.1. Visual core description lithology

Subunit 2A is an olive-black (10Y 3/1) siliceous vitric mud(stone) with distinctive dark mottles, green color banding, episodic darker black laminae, and occasional disseminated pumice. In Section 405-C0019M-5H-1, the sediments are softer (less lithified) than, but a similar color to, those in Subunit 1. Subunit 2A is present in Hole C0019M from 33.00 mbsf (5H-1, 0 cm) to 107.50 mbsf and in Hole C0019J from 83.00 to 141.24 mbsf (7K-2, 0 cm) (Figure F29; Table T13). The background mottled siliceous vitric mud(stone) is occasionally interbedded with intervals (several centimeters thick) of inclined and deformed gray ash layers (Figure F36) and coarser grained gray to olive-black graded beds.

Throughout Subunit 2A, dark gray to black mottles (identified in some locations as iron mono-sulfides) and pyrite-rich patches are present and are particularly evident on XCT images. The black mottles disappeared quickly after being exposed to air (~2–3 h after splitting). Sedimentary structures include occasional color banding (0.5–1.5 cm thick), graded sand beds (e.g., Section 405-C0019M-5H-7), interspersed ash horizons (e.g., Section 5H-2), and granule-, cobble-, to boulder-grade intraformational clasts that sometimes internally preserve grading (e.g., Section 8H-3). Many of the sedimentary structures are inclined (see Structural geology), with occasional downward steepening of the dip (e.g., Sections 7H-2, 70 cm, to 7H-4, 102 cm) underlain by a discordant sedimentary contact with the black mottled mudstone (Section 7H-4, 102 cm; Figure F36).

A total of 17 light yellowish gray to light olive-gray ash layers were identified in Subunit 2A, varying from several centimeter-thick wavy layers to discontinuous elongate patches up to a few centimeters long. These layers typically appear bright in XCT images. Disseminated pyritized pumice clasts are common throughout Subunit 2A. The edges of the ash-rich layers exhibit interfingering with the surrounding background sedimentation (siliceous mud) and display occasional silica mineralization. Burrows can also be observed throughout the unit, highlighted by subtle mottling, pyritization, and patches of different colors ranging from olive-brown to dark gray. Isolated, simple, nonbranching burrows in discrete layers visible in core and XCT images are interpreted as Planolites.

4.1.2.1.2. Smear slide petrography

The grain size of the background sedimentation in Subunit 2A predominately plots as mud (Figures F31, F37) with 0%–55% sand, 10%–95% silt, and 5%–89% clay (Table T14). The composition of the background sedimentation is also a variable mixture of siliciclastic (1%–86%), volcanic (0%–49%), and biogenic (1%–95%) material. The siliciclastic material is mostly clay minerals (0%–75%) with subordinate quartz (0%–35%) and mudstone aggregates (0%–32%). Volcanic material is mostly clear glass (0%–48%), colored glass (0%–4%), and pumice (0%–12%). Biogenic material is mostly diatoms (0%–53%), radiolarians (0%–54%), silicoflagellates (0%–7%), and sponge spicules (0%–50%). Other material (0%–25% of total composition) includes occasional pyrite framboids, dense and opaque minerals, and calcite.

The interbedded ash layers are generally coarser and plot as silt to sand (Figure F31) with 0%–60% sand, 40%–100% silt, and 0%–40% clay. Compositionally, they plot in the siliceous to siliceous-vitric mud sections and are composed of siliciclastic (0%–18%), volcanic (61%–98%), and biogenic (0%–20%) material (Table T14).

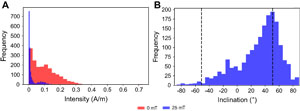

4.1.2.1.3. Mineralogy and sediment geochemistry