Kodaira, S., Conin, M., Fulton, P., Kirkpatrick, J., Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., and the Expedition 405 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 405

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.405.102.2025

Expedition 405 methods1

![]() J. Kirkpatrick,

J. Kirkpatrick,

![]() P. Fulton,

P. Fulton,

![]() K. Ujiie,

K. Ujiie,

![]() M. Conin,

M. Conin,

![]() C. Regalla,

C. Regalla,

![]() S. Kodaira,

S. Kodaira,

![]() N. Okutsu,

N. Okutsu,

![]() L. Maeda,

L. Maeda,

![]() S. Toczko,

S. Toczko,

![]() N. Eguchi,

N. Eguchi,

![]() P. Bellanova,

P. Bellanova,

![]() C. Brown,

C. Brown,

![]() M. Brunet,

M. Brunet,

![]() M. Castillo,

M. Castillo,

![]() Y.-C. Chang,

Y.-C. Chang,

![]() M.-L. Doan,

M.-L. Doan,

![]() J. Everard,

J. Everard,

![]() A. Fintel,

A. Fintel,

![]() J. Ford,

J. Ford,

![]() R. Fukuchi,

R. Fukuchi,

![]() A. Gough,

A. Gough,

![]() H. Guo,

H. Guo,

![]() D. Gürer,

D. Gürer,

![]() R. Hackney,

R. Hackney,

![]() M. Hagino,

M. Hagino,

![]() Y. Hamada,

Y. Hamada,

![]() H. Hosono,

H. Hosono,

![]() A. Ijiri,

A. Ijiri,

![]() M. Ikari,

M. Ikari,

![]() T. Ishikawa,

T. Ishikawa,

![]() M. Iwai,

M. Iwai,

![]() T. Jeppson,

T. Jeppson,

![]() M.-J. Jurado,

M.-J. Jurado,

![]() N. Kamiya,

N. Kamiya,

![]() T. Kanamatsu,

T. Kanamatsu,

![]() A. LaPlante,

A. LaPlante,

![]() W. Lin,

W. Lin,

![]() A. Miyakawa,

A. Miyakawa,

![]() Y. Morono,

Y. Morono,

![]() Y. Nakamura,

Y. Nakamura,

![]() U. Nicholson,

U. Nicholson,

![]() H. Okuda,

H. Okuda,

![]() P. Pei,

P. Pei,

![]() C. Pizer,

C. Pizer,

![]() T. Rasbury,

T. Rasbury,

![]() R.V.M. Robertson,

R.V.M. Robertson,

![]() C. Ross,

C. Ross,

![]() S. Satolli,

S. Satolli,

![]() H. Savage,

H. Savage,

![]() K. Schaible,

K. Schaible,

![]() S. Shreedharan,

S. Shreedharan,

![]() H. Sone,

H. Sone,

![]() C. Sun,

C. Turel,

C. Sun,

C. Turel,

![]() T. Uchida,

T. Uchida,

![]() A. Yamaguchi,

A. Yamaguchi,

![]() Y. Yamamoto,

Y. Yamamoto,

![]() T. Yoshimoto,

T. Yoshimoto,

![]() J. Zhang,

A. Wspanialy,

J. Zhang,

A. Wspanialy,

![]() E. Le Ber,

E. Le Ber,

![]() M.B. Rydzy, and

N. Schuba2

M.B. Rydzy, and

N. Schuba2

1 Kirkpatrick, J., Fulton, P., Ujiie, K., Conin, M., Regalla, C., Kodaira, S., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., Bellanova, P., Brown, C., Brunet, M., Castillo, M., Chang, Y.-C., Doan, M.-L., Everard, J., Fintel, A., Ford, J., Fukuchi, R., Gough, A., Guo, H., Gürer, D., Hackney, R., Hagino, M., Hamada, Y., Hosono, H., Ijiri, A., Ikari, M., Ishikawa, T., Iwai, M., Jeppson, T., Jurado, M.-J., Kamiya, N., Kanamatsu, T., LaPlante, A., Lin, W., Miyakawa, A., Morono, Y., Nakamura, Y., Nicholson, U., Okuda, H., Pei, P., Pizer, C., Rasbury, T., Robertson, R.V.M., Ross, C., Satolli, S., Savage, H., Schaible, K., Shreedharan, S., Sone, H., Sun, C., Turel, C., Uchida, T., Yamaguchi, A., Yamamoto, Y., Yoshimoto, T., Zhang, J., Wspanialy, A., Le Ber, E., Rydzy, M.B., and Schuba, N., 2025. Expedition 405 methods. In Kodaira, S., Conin, M., Fulton, P., Kirkpatrick, J., Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., and the Expedition 405 Scientists, Tracking Tsunamigenic Slip Across the Japan Trench (JTRACK). Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 405: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.405.102.2025

2 Expedition 405 Scientists’ affiliations.

1. Introduction

This chapter documents the methods used for shipboard measurements and analyses during International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 405, Tracking Tsunamigenic Slip Across the Japan Trench (JTRACK). We conducted riserless operations at Sites C0019 and C0026 (Table T1). Two temperature sensor observatories were installed at Site C0019. Logging while drilling and coring were performed at Sites C0019 and C0026. Methods for postexpedition research conducted on Expedition 405 samples and data will be described in individual scientific contributions published after the expedition.

All shipboard scientists contributed to the completion of this volume. Because of the long length of Expedition 405 (106 days, 6 September–20 December 2024), staffing was staggered. The shipboard science party was divided into two science party staffing windows. Window 1 included 26 scientists (6 September–30 October), and Window 2 included 25 scientists (25 October–21 December). The Window 1 to Window 2 handover occurred during a 6 day crossover period with staggered onboarding and offboarding. Six Co-Chief Scientists served in overlapping shifts of two or three at a time, and at least one Expedition Project Manager was on board at all times.

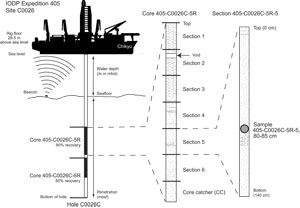

1.1. Numbering of sites, holes, cores, sections, and samples

Sites drilled by the drilling vessel (D/V) Chikyu are numbered consecutively from the first site with a prefix “C.” A site refers to one or more holes drilled while the ship is positioned within 300 m of the first hole, and a letter suffix distinguishes each hole drilled at the same site. The first hole drilled at a given site is assigned the site number modified by the suffix “A,” the second hole takes the site number and the suffix “B,” and so forth (Figure F1). To avoid confusion with numbers and letters, I and O are not used as hole letter suffixes. Hole suffixes are assigned regardless of recovery as long as penetration takes place. Note that during Expedition 405, Chikyu returned to Site C0019, which was previously drilled during Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 343, Japan Trench Fast Drilling Project (JFAST). Therefore, the hole assignments for Expedition 405 begin with C0019F, which continues from the last hole (C0019E) drilled during Expedition 343.

Cores taken from a hole are numbered sequentially from the top of the hole downward. Core numbers and their associated cored intervals are unique in a given hole (Figure F1). The core number is followed by a letter suffix that indicates the type of coring system. The coring systems used during Expedition 405 are as follows:

- A hydraulic piston coring system (HPCS; core type = H). This system is equivalent to the advanced piston corer (APC) system used on the research vessel (R/V) JOIDES Resolution.

- An extended shoe coring system (ESCS; core type = X). This system is equivalent to the extended core barrel (XCB) system used on JOIDES Resolution.

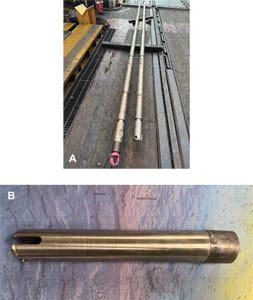

- A small diameter rotary core barrel (SD-RCB) system (core type = K). This system was newly developed for use on Chikyu during Expedition 405.

The cored interval is measured in meters below seafloor according to depth determinations described in IODP Depth Scales Terminology (https://www.iodp.org/policies-and-guidelines). This depth scale is equivalent to the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) meters below seafloor (mbsf) depth scale. In general, depth below seafloor is determined by subtracting the water depth estimated from the initial drill pipe measurement to the seafloor from the total drill pipe measurement. The depth interval assigned to an individual core begins with the depth below seafloor at which coring began and extends to the depth through which coring advanced. For some measurements, depths are reported in meters below rig table (m BRT), such as logging-while-drilling (LWD) data and major faults or lithologic boundaries. This was done to provide a common datum for depth correlations between cores, log, and seismic data, which was necessary where the seafloor was not flat. The rig table on Chikyu is 28.5 m above sea level.

Core depths and recoveries are calculated based on the total advance and recovered core length. For each core, recovery is typically calculated based on a 9.5 m advance, which corresponds to the standard core barrel length for each coring system. However, some Expedition 405 SD-RCB cores had short advances of ~3–5 m to promote core recovery in key intervals. Short advances were applied in the ~20 m above and below the plate boundary to the top of the chert at Site C0019 and in the pelagic clay to chert interval at Site C0026. In addition, HPCS cores may have advances less than 9.5 m if there is partial penetration of the core barrel. Partial penetration of the HPCS core barrel is generally detectable while coring by measuring the pressure drop in the hydraulic system that powers the piston core. Partial pressure drop and gradual release of pressure are used to calculate the estimated penetration depth in these cases. Total recovery may be less than 100% if there are gaps due to nonrecovered material. Total recovery may be greater than 100% if there is core expansion or sucked-in materials, which can be especially prevalent in shallow HPCS cores. Core depths are converted to the core depth below seafloor, Method A (CSF-A), scale, in which overlapping sections are compressed when recovery is >100%. Short cores (incomplete recovery) are all assumed to start from the initial depth of the advance for that core by convention.

A recovered core is typically divided into ~1.4 m long sections that are numbered sequentially from 1, beginning at the top. Section length varies from core to core because the locations for cutting sections are chosen to avoid intervals of scientific interest. Material recovered from the core catcher is assigned to a separate section, labeled core catcher (CC), and placed at the bottom of the lowermost section of the recovered core.

A full identification number for a sample from a core section consists of the following information: expedition, site, hole, core number, core type, section number, and top to bottom interval in centimeters measured from the top of the section. For example, a sample identification of “405-C0026C-6K-5, 80–85 cm,” represents a sample removed from the interval between 80 and 85 cm below the top of Section 5 of the sixth core taken with the SD-RCB from Hole C0026C during Expedition 405 (Figure F1). In this report, sample depths are reported to the nearest 0.5 cm when using full identification numbers. Sample or interval depths reported on the mbsf, meters below sea level (mbsl), or m BRT scales are rounded to the nearest centimeter.

1.2. Core handling

The following sections describe the flow of core from the drill floor through the laboratory. Core handling during Expedition 405 followed the general core flow procedure implemented during recent IODP expeditions on Chikyu but was optimized to process and store the samples properly for the scientific objectives of the expedition. The specific core flow for this expedition is illustrated in Figure F2.

1.2.1. Core cutting area

As soon as a core was retrieved on deck, the core catcher was delivered to the core cutting area. A ~5 cm whole round was taken for micropaleontological analysis, and the remainder of the core catcher sample was packed into a core liner and entered into the general core flow. The core was then transferred to the core cutting area. The recovered core length and the total length of void space were then measured and entered into the J-CORES database, along with core identification information, drilling advance, recovery, and depth information. Void space gas samples were collected if appropriate sample locations were identified. The core was cut into sequentially numbered ~1.4 m long sections. Two small (5 cm3) plugs of sediment were immediately removed from the bottom of appropriate core sections for headspace gas analysis, typically from the base of the first section. In addition, samples of the liner fluid, where present, were collected for geochemical analysis. Each section was then sealed at the top (blue cap and blue tape) and bottom (clear cap and white tape). All sections were marked and labeled, and sections were moved to the core processing deck.

For hard rock cores (405-C0019P-1K through 5K), core flow in the core cutting area was modified. If recovered materials were discontinuous pieces, each piece was extracted from the core liner in the core cutting area, pieces were then pushed to the bottom of the 1.4 m liner sections, and the total rock length was measured. Pieces were subsequently put into split plastic liners in consecutive order. Each piece of core was marked on the bottom with a red wax pencil to preserve orientation through the subsequent core flow. Broken pieces that could be fit together along fractures were curated as single pieces. A watchdog assigned from the structural geology and/or sedimentology visual core description team confirmed piece matches. The split line, which defined how the pieces were to be cut into two equal halves, was marked on all pieces, with a continuous line applied across broken pieces that were fit back together as single pieces. The working half was labeled with the letter “W,” and the archive half was labeled with the letter “A.” For the archive half, a plastic spacer was welded with an ultrasonic welding machine to the split core liner between individual pieces or reconstructed contiguous groups of subpieces. These spacers may represent substantial intervals of no recovery. The length of each section of core, including spacers, was entered into the database as “curated length.”

1.2.2. Core processing deck

All sections except for Section 405-C0019J-4K-1 and Cores 5K–10K were scanned using the X-ray computed tomography (XCT) scanner (GE Healthcare Discovery 750HG) (see Structural geology). For Section 4K-1 and Cores 5K–10K, XCT imaging was only performed on the split section (archive half) and whole-round core samples because of a temporary malfunction of the XCT scanner.

Each shift had a structural geologist acting as a watchdog to oversee the collection and selection of whole-round core samples to identify sections or intervals of special interest or unique characteristics that should be avoided for whole-round sampling to prevent destruction of any critical samples. For sections of sedimentologic interest, a sedimentology computed tomography (CT) watchdog helped approve samples.

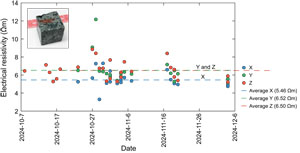

Following XCT scanning and time-sensitive whole-round core sampling, core sections were allowed to equilibrate to ambient laboratory temperature (2–3 h; ~20°C), after which they were run through the Core Measurement Track (COMET; NS Design) (see Physical properties) to measure gamma ray attenuation (GRA) bulk density, P-wave velocity, magnetic susceptibility (MS), and natural gamma radiation (NGR). Thermal conductivity (TeKa TK04) measurements were also made on whole-round core sections for soft-sediment cores. After COMET and thermal conductivity (soft-sediment) measurements, non-time-sensitive whole-round core samples were taken based on examination of the XCT images. Cut section ends were sealed with a yellow cap to indicate removed whole-round core samples.

After completion of all the above measurements and sampling on whole-round cores, the core sections were split axially into working and archive halves. The archive half was subject to lithologic visual core description and smear slide analysis, nondestructive measurements/observation such as digital photo image scanning, and superconducting rock magnetometer (SRM) measurements. Following these analyses, the archive half was covered in plastic film, shrink-wrapped in plastic, and stored at ~4°C until needed for further analysis. The working half was subjected to structural analysis, shipboard sampling (physical properties [PP], paleomagnetism [PMAG], and X-ray diffraction [XRD]/X-ray fluorescence [XRF]/carbonate [CARB] analyses) and measurements (e.g., impedance analyzer, vane shear strength, and anisotropy of magnetic susceptibility [AMS]), and then sampled for postexpedition research. Following completion of sampling, the working half was also wrapped, sealed, and stored at ~4°C in preparation for shipping to the Kochi Core Center (KCC) in Kochi, Japan. All samples collected are labeled, packaged, stored, and shipped to their final destinations according to standard practice.

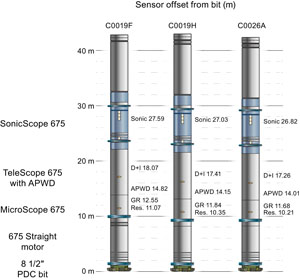

2. Logging while drilling

During Expedition 405, the LWD/measurement-while-drilling (MWD) assembly deployed a combination of three Schlumberger (SLB) logging tools in the following order (from bottom to top): MicroScope HD 675, TeleScope 675, and SonicScope 675. The sections of the bottom-hole assembly (BHA) that include the tools and their respective measurement offsets from the drill bit are illustrated in Figure F3. More details about the location of the sensors are given in Table T2, and the resolution of the measurements are given in Table T3. The tool string collar outer diameter was 6¾ inches (17.526 cm), and it was powered solely by a mud turbine located in the TeleScope 675. Because the tools had no batteries, data collection required fluid circulation greater than 400 gal/min through the TeleScope 675 turbine to power all three tools and send (real-time [RT]) and record (recorded mode [RM]) data. All recorded gamma ray and resistivity and sonic data were stored in the tool memory of the MicroScope and SonicScope, respectively. A lower resolution subset of the data was transmitted to the surface in real time through mud-pulse telemetry. The RT data set also contained a subset of surface drilling parameters (e.g., rate of penetration [ROP], weight on bit, rotations per minute, and torque) that were used for drilling performance monitoring and data quality assessment and control (QA/QC). The memory data were retrieved after recovering the BHA to the surface.

2.1. LWD/MWD acquisition systems and tools

2.1.1. Depth tracking system

LWD/MWD data are recorded as a function of time. The tool clock is synchronized with the clock inside the SLB Maxwell data acquisition system on board. The Maxwell system is used to communicate with and receive data from the tools downhole using continuous mud-pulse telemetry while fluid circulation greater than 400 gal/min is sustained. In addition, the Maxwell system allows the SLB field engineers to track and monitor depth using a geolograph in combination with the rig’s depth tracking system (utilizing the position of the traveling block from the drill floor, known length of the cable on the drawworks, and known length of the drill pipe). The time-depth correlation created in the Maxwell system can then be used to convert the data timestamps into depth.

For RT data transmission, different configurations were programmed by SLB because the quality and transmission rate of the signal (and its demodulation) received through mud-pulse telemetry can be altered as depth increases. Either MicroScope HD ultrahigh-resolution images (UHRIs) or SonicScope 675 data were to be removed from RT downhole data transmission in case of poor mud-pulse telemetry signal. Tools were set to record data (RM) at three different rates depending on operations. The primary data recording rate was every 10 s, and it decreased to 15 s when drilling progression was slower in harder formation. For the relogged section (Hole C0019H), the rate was set to 1 s.

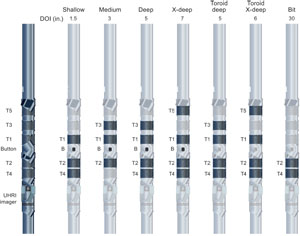

2.1.2. MicroScope HD 675

The MicroScope HD 675 was positioned above the drill bit and mud motor (and in the case of Hole C0019F, a float sub) (Figure F3). Total gamma ray and formation resistivity logs, as well as high-resolution resistivity images, were acquired with the MicroScope HD.

2.1.2.1. Gamma ray

The azimuthal gamma ray tool measures the total background gamma radiation emitted from radioactive elements in the formation. The gamma ray detector is located toward the top of the MicroScope HD (Table T2) and measures the average value of incoming gamma rays across four quadrants (up/down and left/right) in the formation as the tool rotates. The depth of investigation of the logging tool is relatively shallow (often <50 cm) and depends on formation mineralogy. The gamma ray measurements are also impacted by the borehole size, drilling fluid, and tool design. The gamma ray values are delivered in American Petroleum Institute gamma radiation units (gAPI). The axial resolution of the gamma ray tool is 10 inches (25.4 cm), and its measurement accuracy is listed as 5%.

2.1.2.2. Resistivity

The MicroScope HD contains two button electrodes placed 180° apart with three unequally spaced toroid electrodes above and two below (Figure F4). Using different configurations between buttons and toroids (that can also be used as transmitters and receivers), the MicroScope HD generates focused currents and acquires resistivities at seven different depths in the formation: button resistivity (shallow [1.5 inches; 38.1 mm], medium [3 inches; 76.2 mm], deep [5 inches; 126 mm], and extra deep [7 inches; 177.8 mm]), toroid resistivity (deep [5 inches; 126 mm] and extra deep [7 inches; 177.8 mm]), and bit resistivity (30 inches; 762 mm). For the button resistivity measurements, the buttons act as measurement electrodes, two toroids act as transmitters (radial current), and one or two toroids act as monitors (axial current through the tool). For the toroid resistivity measurements, toroids can serve as transmitter, monitor, or measurement electrodes depending on the depth of investigation targeted. When measuring bit resistivity, the closest toroid to the bit induces an axial current that travels down the tool. The current exits at the bit and returns to the second closest electrode to the bit. The geometry of the borehole assembly is taken into account to compute the geometrical factor of the bit resistivity measurement. For more details about the tool measurement principles, refer to Allouche et al. (2010). Resistivity curves were used by SLB to calculate an estimate of the borehole diameter (e-caliper).

2.1.2.3. Resistivity images

Button resistivity measurements (Figure F4) are acquired during downhole tool rotation only. They are recorded and processed to produce a 360° resistivity image of the borehole wall with 56 azimuthal bins. The button electrode measures resistivity at four depths of investigation that depend on the ratio between the resistivity of the invaded zone and the resistivity of the formation. In an 8.5 inch borehole (20.32 cm), SLB tool specification indicates that the shallow, medium, deep, and extra deep button resistivities have depths of investigation of 1.5 inches (38.1 mm), 3 inches (76.2 mm), 5 inches (12.7 mm), and 7 inches (17.8 mm), respectively (Table T3). The MicroScope HD is also mounted with an UHRI sleeve equipped with eight button electrodes. UHRIs are divided into 208 azimuthal bins and have an axial resolution of 0.4 inches (10.16 mm), better than the axial resolution of the resistivity image (1.5 inches = 38.1 mm). The tool’s orientation system uses Earth’s magnetic field as a reference to determine the tool position with respect to the borehole as the drill string rotates.

2.1.3. TeleScope 675

The TeleScope 675 is located above the MicroScope HD and below the SonicScope 675 (Figure F3; Table T2). The tool serves as a power generator for the MWD/LWD present in the BHA, provides mud-pulse telemetry, takes borehole directional surveys, and measures annular pressure and temperature. It contains a hydraulic mud turbine and electrical power generator that generate electricity as the drilling fluid is pumped through the system. The electricity is used to power the other MWD/LWD tools of the BHA and enables intertool communication and data connectivity.

A magnetometer and accelerometer inside the TeleScope 675 measure borehole azimuth and inclination, respectively. Static borehole survey data are taken when the drill pipe is not moving generally after stand connection (i.e., between stands every 90 m). Continuous azimuth and inclination are also acquired during drilling. Because of the drilling-induced vibrations, the continuous inclination values are less accurate than the static values.

RT data transmission is performed through mud-pulse telemetry. A modulator (rotating valve) present in the TeleScope 675 creates a continuous oscillating pressure pulse that propagates through the drilling fluid up the drill pipe. At the surface, the fluid pulse oscillations are decoded into numerical values. The bandwidth of mud-pulse telemetry during Expedition 405 was 3–4 bits per second (bits/s, or bps).

2.1.4. SonicScope

The SonicScope 675 is located at the top of the logging tool assembly (Figure F3). The tool comprises both monopole and quadrupole acoustic transmitters. The monopole transmitter generates a dilatational wave that travels radially out from the tool, and the quadrupole transmitter generates perpendicular dilation and compression. The arrival times of the compressional and shear waves are measured at an array of 48 receivers spaced over 12 levels, 4 inches apart vertically and 90° apart radially (Table T2). The SonicScope 675 has a vertical resolution of 10 inches (Table T3) and stored stacked waveform data from 12 receiver levels at 10 s intervals. First P-wave arrivals were picked from high-frequency monopole data automatically based on semblance and slowness-time-coherence information within the SLB processing workflow. For slow formations, Leaky P analysis was required (Wang et al., 2020). For Leaky P, the reference QC curve is the slowness-frequency analysis obtained from dispersion analysis of the low-frequency band of the monopole waveforms; the picked slowness should lie on the left edge of the slowness-frequency analysis projection (Plona et al., 2006). Shear wave slowness was extracted from model-based inversion of the quadrupole sonic data (Alford et al., 2012). Final P-wave logs were delivered as composite logs, stitching different depth intervals processed with different methods depending on data quality.

2.2. Shipboard data flow and quality check

The RT data is easily accessible to scientists through live on-screen logs and digital files delivered every 12 h. However, the quality of the RT data is somewhat reduced because of the limitations of mud-pulse telemetry. On the other hand, the memory (RM) data sets offer higher resolution measurements to produce a more detailed insight into downhole conditions and geologic structures.

All depth-converted LWD/MWD data were provided in digital log information standard (DLIS) format by the SLB field engineers. Additionally, a subset of RT time-based and both RT and RM depth-based curves were also delivered as log ASCII standard (LAS) files.

Data delivery from SLB consisted of the following:

- RT data displayed on witness screens as drilling progressed, with the possibility to adjust/modify the reference (depth or time) and displayed tracks;

- RT data every 12 h, provided by the field engineers on board as DLIS and LAS files;

- Rush RM data after recovering the tool (consisting of most logs except SonicScope data, processed data, and e-caliper estimation), provided by the field engineers as DLIS and LAS files;

- SonicScope 675 processed RM data, provided from the shore-based analysis and interpretation team as DLIS and LAS files;

- Reprocessed RM MicroScope HD images, provided from the shore-based analysis and interpretation team as DLIS and LAS files (for Hole C0026A where only RT data were available, RT UHRIs were reprocessed by SLB to improve data quality);

- E-caliper estimation from RM MicroScope HD data, provided from the shore-based analysis and interpretation team as DLIS and LAS files (for Hole C0026A where no RM data was recovered, the e-caliper was calculated based on RT data); and

- Final well construction measurement RM field data, provided by the field engineers as DLIS and LAS files.

After defining the position of the mudline on the gamma ray and resistivity logs, all logging data were depth shifted to the seafloor (LWD depth below seafloor [LSF] depth scale). The depth-shifted versions of the LWD/MWD data were made available in DLIS format, and the main scalar logs were also made available as LAS files. All files were distributed to the shipboard scientists using the shipboard intranet data servers. Analyses, integration results, and reports produced by the shipboard scientists were archived on the server for further distribution. The MicroScope HD resistivity images were processed on board Chikyu using the SLB Techlog (version 2023) software package.

Both the SLB field engineers and Logging Staff Scientists used drilling mechanics logs to identify the sequence of drilling events and assess any possible impact on data quality. The SLB engineers informed the Logging Staff Scientists and drilling engineers of any concerns (e.g., MWD signal quality, stick-slip, shock and vibration flags, and ROP/rpm ratio) that could affect overall data quality. The SLB and drilling engineers adjusted drilling parameters accordingly to ensure the best balance between drilling progress and data quality. Drilling mechanics logs include drilling surface parameters (e.g., ROP, surface weight on bit [SWOB], hook load [HKLD], and standpipe pressure [SPPA]) and downhole drilling parameters (e.g., collar [bit] rotation [CRPM], survey data, shock rate [SHKR], and stick ratio [STICKRATIO]). Elapsed time of the main geophysical measurements after bit penetration, including annular pressure and temperature logs, were also assessed to identify any anomalous zones. To obtain the best image quality from the MicroScope HD, the SLB engineers recommended the ratio between ROP (in m/h) and rpm (in c/min) remain below 0.6. These recommendations were followed throughout the majority of the drilling operations during Expedition 405. It is worth noting that the overall quality of the logs and data is good; however, caution should be exercised when interpreting the images because they were affected by stick-slip, shocks, and heave motion.

2.3. Log characterization and log unit definitions

LWD measurements provide in situ petrophysical information on sediment, rock, and pore fluids while the hole is being drilled, as well as 360° oriented images of the borehole wall. These measurements are sensitive to changes in composition, texture, and structure. Changes in the log response are commonly associated with geologic unit boundaries. This section addresses the characterization of LWD measurements and imaging tool response, focusing on dividing the well logs into log units. For Expedition 405, the aim was to provide a preliminary assessment of expected lithostratigraphy from LWD data prior to coring.

2.3.1. Log characterization and identification of logging units: qualitative analysis

The borehole interval over which LWD logs were acquired was separated into log units by qualitative examination of the log responses and downhole trends: the variations in log curve shape and magnitude, as well as peak amplitude and frequency, and thorough examination of the image logs. Natural radioactivity, resistivity, sonic velocities, and borehole images were the main input logs for determining unit boundaries. In addition to defining and characterizing the logging units, the logging team identified any compositional features/variations within each unit and interpreted them in terms of geological features (unit boundaries, transitions, sequences, and likely lithologic composition).

2.3.2. Log-based geologic/lithologic interpretation

After log characterization and classification, logs were lithologically and geologically interpreted using a combination of log characteristics and borehole images. Composition-sensitive logs, such as NGR, were used to determine unit-scale to bed-scale lithology, and resistivity logs were used to identify lithologies with different physical properties, such as mudstone, chert, and basalt. Borehole images provided information used to identify and characterize other geological features such as bedding, sedimentary structures, bed boundaries, and faults. Interpretation was also informed by existing data from nearby ocean drilling sites.

2.4. Physical properties

We present the resistivity, sonic, and gamma ray logs as a function of depth and describe their features and variation, considering information from structural geology and seismic reflection data. Statistical summaries of these petrophysical properties were compiled for each logging unit. Sharp variations in physical properties are of particular interest because they can be indicators of a fault zone, permeable horizon, or lithologic change. Gradual transitions are also potent indicators of damage and compaction trends.

2.5. Structural analysis: bedding, fractures, and faults

Structural analysis was performed primarily on MicroScope resistivity images using Techlog (SLB Ltd.) software. Resistivity images show the borehole wall as a planar “unwrapped” 360° image. The orientations of planar surfaces cutting the borehole (bedding, fractures, and faults) are identified through sinusoidal fitting of the unwrapped image. In identifying bedding, care must be taken to avoid horizontal artifacts caused by problems in data acquisition that appear as sharp horizontal lines. For shipboard analysis, the dips of the picked planar structures were computed using the bit size as the borehole diameter. We distinguished fractures, faults, and bedding from one another by looking for crosscutting relationships. The fractures and faults were classified as to whether they were conductive, resistive, or undetermined/unclassified. Where resolved, the thickness of faults and fractures was noted.

2.5.1. Borehole wall failure analysis

Borehole breakouts and tensile fractures are wall failures that form when the state of the local stress field at the borehole wall exceeds rock/sediment strength (Zoback, 2007). In a vertical borehole, breakouts form along the borehole in the direction of the minimum horizontal stress (Shmin) and perpendicular to the maximum horizontal stress (SHmax). Breakouts are recorded in resistivity images as two parallel conductive vertical features 180° apart. We recorded the orientation and width of breakouts with the available image analysis software, considering all three borehole images (shallow, medium, and deep), and determined the maximum and minimum horizontal stress orientations.

3. Lithostratigraphy

Characterization of sediments encountered during Expedition 405 required the development of a consistent methodology that could (1) be efficiently applied during two shifts and two windows of shipboard scientists during the expedition and (2) produce consistent and informative data for future analysis. To keep consistency with previous IODP expeditions, the applied approach considered previous drilling reports from the Japan Trench area targeting similar sediments across the accretionary prism, the trench, and the incoming plate (e.g., Deep Sea Drilling Project [DSDP] Legs 56 and 57, Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 343/343T, and IODP Expedition 386, [Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980; Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013b; Ikehara et al., 2023]). Several methodologies were used to summarize the lithologies: (1) visual core descriptions to qualitatively document primary observations (e.g., sedimentary structures, textures, color, and composition) at the macroscale, (2) smear slide analysis of sediment to provide a semiquantitative estimate of grain size and relative siliciclastic/biogenic/volcanic components at the microscale, (3) XCT to provide 3D visualization of changes in density, (4) digital linescan imagery and colorimetry values from the Tri-Sensor Core Logger (TSCL), and (5) XRD and XRF analyses to measure the whole-rock mineral and element composition. The data sets were compiled, and the combined information was used to define discrete lithostratigraphic units named for the primary lithology, with color as an additional descriptor to differentiate similar units (see Classification of lithostratigraphic units).

3.1. Visual core description

Visual core description aimed to characterize variations in grain size, texture, sedimentary structures, and color along the cores. Archive-half cores were observed and described after noninvasive measurements (e.g., XCT and COMET), whole-round sampling, core splitting, and imaging with the TSCL (see Core handling). Visual core description for structural whole-round samples not split on board (e.g., Sections 405-C0019J-56K-5 and 87K-2 and 405-C0019K-10K-2) used the whole-round surfaces. Observations were recorded on visual core description (VCD) sheets. VCD sheets for HPCS, ESCS, SD-RCB system, and hard rock all include columns for visual representation, lithologic boundaries, symbology, bioturbation level, grain size, coring disturbance, and Munsell color. Slight modifications to the layout of the sheets for HPCS/ESCS cores were adapted from those used during Expedition 386 to allow more detailed documentation of subtle grain size changes, sedimentary structures, and features encountered in surficial soft sediments. Bioturbation intensity was separated into light (bedding preserved), moderate (bedding disturbed), or heavy (bedding obliterated).

Specific descriptive terminology generally followed Folk (1954) for siliciclastic sediment classification, with modifications for sediment composition based on site-specific observations and previous IODP volumes (e.g., Expeditions 343 and 386). Further descriptions documented variations in predominant and subordinate lithologies; sedimentary structures; and the nature of contacts between layers, textures, and compositions at the millimeter scale. XCT images of each core section were used during visual core description to aid observations linked to changes in density, identify intervals of drilling-induced deformation, and help distinguish sedimentary structures that are difficult to interpret visually. Upon completion, all descriptions were uploaded to the J-CORES database and the VCD sheets were scanned and archived. A concise summary for each core was included at the end of each J-CORES description.

Visual core description of hard rock cores was conducted for Hole C0019P. Descriptions included lithologic classifications, phenocryst size and mineralogy, crystal abundance, and the presence of vitric components. Because thin sections were not available during the visual core description of hard rock cores, the term “basalt” was generally used for fine-grained mafic igneous rocks and was further classified into pillow basalt and massive basalt based on the meter- to centimeter-scale characteristics and textures observed on split core surfaces. The term “dolerite” was applied to crystalline (or holocrystalline) igneous rocks primarily composed of plagioclase and clinopyroxene. For sedimentary rocks, “chert” was used for silica-rich, glassy rocks that could not be scratched with metal tweezers, and “limestone” was applied to rocks primarily composed of carbonate minerals (undifferentiated), as confirmed by smear slide observations.

For both sediments and hard rocks, the J-CORES database was used to provide stratigraphic summaries of all data sets and samples alongside XCT and TSCL images. To condense the detailed visual core descriptions, several simplifications were required:

- Distinct layering of sediments with slightly different grain size and composition is present throughout the cores (e.g., graded layers of sands and silts). For simplicity, a minimum thickness of >2 cm was adopted for entering this information into the J-CORES database. Layers thinner than 2 cm were recorded using the laminae lithology symbol.

- The lithology of each siliciclastic layer was entered based on its visually estimated grain size descriptor (e.g., clay, sand, or mud) because grain size could be visually estimated for the entire core, whereas composition could only be quantified at discrete locations with smear slide samples (see Smear slide analysis). The volcaniclastic material was grouped under the term “ash.” Lithology was recorded alongside sedimentary features such as bioturbation, color banding, pumice clasts, and so on. Symbology for all lithologies and sedimentary features is shown in Figure F5.

- Subvertical to vertical bedding may result in the coexistence of coarse- and fine-grained layers at the same depths. These intervals were recorded in the J-CORES database based on the dominant grain size composition alongside the chaotic lithology symbology.

- Distinguishing a clear boundary between unconsolidated sediment and lithified rock was challenging because of the gradual nature of consolidation during burial and the interbedding of different lithologies. For all holes except Hole C0019P, individual layers in the J-CORES database were named without differentiation between sediments and rocks. The suffix “-stone” was applied for summarizing the name of the lithostratigraphic units in core sections that required a band saw for splitting.

- Ash layers were assigned in the database as a distinctive lithology (also for thicknesses <2 cm). A single consistent lithology, “ash,” irrespective of grain size differences, was used for clarity and to avoid introducing redundant symbols.

These criteria ensured systematic classification while still reflecting the lithologic characteristics of the sites. Data from the J-CORES database were compiled to make stratigraphic logs using Strater software.

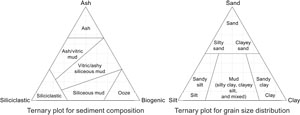

3.2. Smear slide analysis

Smear slide analysis aimed to provide semiquantitative insights into grain size and composition of biogenic, volcanic, and siliciclastic material. One or two smear slides per section were collected from the archive-half cores, targeting representative lithologies. Occasional nonrepresentative samples were collected from specific areas of interest, such as ash layers, calcite veins, and clasts. These samples were clearly marked to ensure they did not influence the overall compositional analysis. Sample depths were recorded and entered into the J-CORES database with a sample code of SS.

Slides were examined in transmitted light using an Axioskop 40A polarizing microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi1 digital camera. At least one representative photograph was taken per sample. Observations were recorded on preformatted sheets (subsequently scanned and archived) for consistent tracking across all samples. The relative percentages of different constituents were estimated with the help of a visual comparison chart (Rothwell, 1989) (Figure F6), while recognizing the presence of personal bias and associated uncertainty in the results. Each major compositional component was divided based on the following criteria:

- Siliciclastic material was divided into quartz, feldspar, clay minerals, and lithic grains, including sedimentary lithics (e.g., chert, mudstone, siltstone/sandstone, and limestone), metamorphic lithics, and plutonic lithics.

- Volcanic material was divided into clear glass, colored glass, pumice, volcanic lithics (e.g., felsitic, microlitic, and lathwork), and altered volcanics.

- Biogenic material was divided into pelagic grains and other bioclasts. The pelagic grains were divided into calcareous microfossils (nannofossils and foraminifers) and siliceous microfossils (diatoms, radiolarians, silicoflagellates, and sponge spicules).

- Other material was divided into other carbonate allochems (e.g., peloids, ooids, etc.), minor grain types (e.g., dense minerals, micas, glauconite, opaque minerals, etc.), and authigenic components (e.g., pyrite, calcite, zeolites, and Fe/Mn oxides).

Visual estimation of grain size also used comparison charts (Rothwell, 1989). However, sand-sized particles may be underrepresented because of potential preferential removal during smear slide preparation, so quantitative estimates may be biased toward fine-grained fractions. Results were uploaded to an abridged spreadsheet for plotting ternary diagrams and downhole trends.

The results from the smear slide analysis were used to summarize the composition of different lithologies. Two sets of ternary plots were used to illustrate the composition and grain size of each unit in the accretionary prism (Site C0019) and incoming plate (Site C0026). Ternary diagrams used for grain size and compositions were adapted from Folk (1954) and Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 308 (Expedition 308 Scientists, 2006), enabling variations in different components across units to be more effectively highlighted. Within the adapted ternary diagram for composition, each apex represents 100% of each respective end-member sediment type (Figure F7). The principal end-members of siliciclastic, biogenic, and volcanic components are therefore normalized to 100% in reported figures. This means sediment compositions dominated by more than two-thirds (>66.6%) of a single component are classified as ash, siliciclastics, or ooze, respectively. For sediments containing one- to two-thirds (~33.3%–66.6%) siliciclastic, volcanic, or biogenic components, a compositional modifier (vitric, siliceous, or siliceous vitric) was added to further characterize intermediate sediment. The terms “vitric” and “siliceous” were used instead of “ashy” and “biogenic” because most of the volcanic grains observed during Expedition 405 were vitric (i.e., mainly volcanic glass and pumice; rare lithic and volcanic minerals), and most of the biogenic grains were siliceous (i.e., diatom, radiolarian, siliceous spicule, or silicoflagellate); however, we noted the presence of calcareous nannofossils and foraminifers where present.

The adapted ternary diagram for grain size distinction was governed by three visually distinguishable end-members of sand (>63 µm), silt (63–4 µm), and clay (<4 µm). Sediment composed of >50% sand was classified as sand. Three segments divide the remaining <50% siliciclastic portion between silt and clay end-members. Between the >75% end-member silt and clay portions, “mud” was used to summarize sediments with mixed composition (e.g., silty-clay, clayey-silt, and equally mixed). The combination of composition and grain size descriptors from these two ternary plots defined the sediment type for each smear slide sample.

3.3. Split core digital photography

Split core digital photography imaging on the TSCL acquires color spectrophotometry and illustrates color variations across different units. The NS Design TSCL was used to capture continuous digital linescan imagery of each archive-half core. TSCL imaging was conducted as soon as possible after core splitting to avoid time-dependent color changes resulting from sediment drying and oxidation. Cores were prepared by carefully removing bumps, dust, and (core splitting–related) plastic particles on the split core surface. TIFF-formatted images were obtained with a spatial resolution of 100 pixels/cm (2K) and occasionally at 200 pixels/cm (4K) in sections with high-resolution changes. Scanned images and data were uploaded to the J-CORES database so that image files could be observed through the Composite Log Viewer. Linescans were modified to enhance image contrast using the plugin Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) in the open-source Fiji image processing package (LOCI University ImageJ). This plugin enhances contrast by applying histogram equalization to small, localized regions (tiles) of the image rather than the entire image. This method is particularly effective for improving visibility in areas with poor contrast or uneven illumination. To prevent noise amplification, CLAHE includes a clipping threshold that limits the enhancement of high-frequency variations, ensuring a balanced and clear result. Applying this plugin to linescans allowed us to distinguish color changes, structures, and contacts that might be difficult to see with the naked eye. In addition to TIFF images, the camera provides a measure of 16 bit red-green-blue (RGB) colorimetry. Quantitative colorimetry data are available for Holes C0019J and C0019K but not for some cores from Holes C0026B, C0019E, C0019L, C0019M, and C0019P because of a failure of the sensor partway during operations.

3.4. X-ray computed tomography

XCT offers a 3D view of sediment cores. Shipboard XCT scanning was performed on whole-round cores directly after section cutting. The shipboard medical-grade XCT scanner (Discovery CT 750HD) acquires radiographic images with a slice thickness of 0.625 mm. The resulting data consist of core-axis-normal planes of X-ray attenuation values recorded at a resolution of 512 pixels × 512 pixels per slice. The results are a sequence of radiographic images collected from a 360° perspective, generating 2D cross-sectional core images. Raw data were stored on the server in the Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine (DICOM) format.

Initially, a preliminary 3D model reconstructed from stacked radiographic images was used to guide the selection of sections for whole-round shipboard sampling. Afterward, raw XCT data were processed using HOROS software and the Fiji package. Images are displayed in grayscale, with brighter areas indicating higher CT numbers (e.g., sand/ash layers) and darker areas showing lower CT numbers (e.g., bioturbated intervals, air, or fractures). The CT number (also known as the Hounsfield unit [HU]) is a measure of the relative density of scanned materials (Renter, 1989), and its variations represent the attenuation of X-ray beams while passing through different materials (e.g., air CT number = −1000; water CT number = 0). Variations in the downcore CT number can therefore be used as an additional quantitative proxy for distinguishing density differences and boundaries between lithostratigraphic units. Thus, the resulting 2D images were used to support visual core descriptions by highlighting sedimentary and structural features that were obscured or invisible on the split core surface.

3.5. X-ray diffraction

To further characterize sediment composition within lithostratigraphic units, bulk powder XRD analysis was conducted to examine downcore trends in mineralogy. At least one 2–2.5 cm long quarter-round bulk sample for XRD, XRF, and CARB per core was taken from representative intervals within each unit. Bulk samples were vacuum-dried at room temperature for 24 h before being crushed to a fine powder with a tungsten ball mill. The powdered sample was divided into three glass vials, one each for XRD, XRF, and CARB measurements, with approximately 4 g of the powder reserved for XRD. The XRD sample was mounted to a backload-type sample holder as a pressed powder and measured using a PANalytical CubiX3 X-ray diffractometer. The instrument settings were as follows:

- Generator = 40 kV and 45 mA.

- Tube anode = Cu.

- Wavelength = 1.54184 Å (CuKα).

- Step spacing = 0.01°2θ.

- Rate = 0.1 s/step.

- Slits = automatic.

- Measuring diameter = 10 mm.

- Scanning range = 2°–60°2θ.

XRD spectra were exported from the PANalytical X’Pert software with labels highlighting peaks corresponding to the individual mineral phases present in the samples. To provide semiquantitative estimates for relative abundances of four major mineral components (quartz, plagioclase, calcite, and clay), a least-squares best-fit approach was used against a reference XRD spectrum defined from standards (Underwood et al., 2003) prepared by Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 316 Scientists for the Nankai Trough sediments (Expedition 316 Scientists, 2009a). However, there are many potential limitations in estimating a range of mineral components from XRD in this way, largely related to the difference in peak response between poorly crystalline minerals at low diffraction angles (e.g., clay minerals) and highly crystalline minerals at higher diffraction angles (e.g., quartz and plagioclase). It should also be noted that these approximations also do not allow for the detection of other components such as glass or alkali feldspar from volcanic sources or opaline biogenic silica and therefore should be considered as the upper bounds. These issues are extensively reported by Expedition 316 Scientists (2009a), but the use of this analysis remains valuable for rapidly approximating relative proportional mineralogy during expeditions, hence its inclusion alongside figures of bulk XRD spectra for Expedition 405.

3.6. Loss on ignition and X-ray fluorescence

Approximately 10 g of dried powder was subsampled for XRF and loss on ignition (LOI) analyses from the same sample used for XRD and CARB. The subsampled powder was weighed, heated to 100°C for 2 h to remove moisture, and reweighed. Samples were then ignited at 1000°C for 3 h to remove all volatiles and reweighed a final time. Weight differences of the samples between the two heating processes were used to calculate the LOI, reported as weight percent of the original mass of the sample. LOI provides an estimate of organic material, carbonate minerals, or other volatiles that are removed during heating of sediment samples to high temperatures. This analysis can be done during the preparation of glass beads for XRF spectrometry, which provides data on the bulk sample elemental composition.

Subsamples (0.8950–0.9040 g) of the ignited material were fused with 4.5 g of Spectromelt A12 flux for 7 min at 1150°C to create glass beads for XRF analysis. Measurements were performed on the wavelength dispersive XRF spectrometer Zetium (PANalytical) equipped with a 2400 W rhodium anode X-ray tube at 60 kV and 100 mA. Data were reported as total counts on the peak and as semiquantitative oxide weight percent (Na2O, MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, P2O5, K2O, CaO, TiO2, MnO, and Fe2O3).

3.7. Classification of lithostratigraphic units

The primary criteria used to classify boundaries between lithostratigraphic units were variations in grain size and/or composition, as defined from visual core description and smear slide analysis. However, because much of the sediment described displayed only subtle variations in composition, color changes identified during visual core description and confirmed with colorimetry values (where available) were also considered as differentiating criteria. For example, several boundaries were characterized by gradual rather than abrupt changes in composition and color. As a result, many lithostratigraphic units include a zone of gradational changes in both color and composition. Units with internal gradational color changes that were not necessarily accompanied by major compositional changes were separated into subunits.

After depth boundaries were defined, lithostratigraphic units were numbered from the top to the bottom of the cored interval at each site. For Holes C0019J, C0019L, and C0019M, continuous unit numbers were adopted to reconstruct the longest possible composite lithostratigraphy section through Site C0019. However, Hole C0019K was described separately (unit names are prefaced with the letter K) because it was recovered from an overlapping depth interval with Hole C0019J but showed clear differences, indicating heterogeneity between holes. Hole C0019P was also described separately (unit names are prefaced with the letter P) because the coring depth interval for Hole C0019P was much deeper and different lithostratigraphic units were targeted.

Each lithostratigraphic unit and subunit was assigned an overall descriptor based on the predominant lithology, which we interpret to correspond to the background sedimentation during deposition, and a summary of the following:

- Color: from the Munsell chart defined during visual core description (e.g., olive-black [10Y 2/1]).

- Composition: from ternary plot of smear slides (e.g., siliceous vitric).

- Grain size: from ternary plot of smear slides, cross-checked with visual core description (e.g., mud).

This system provides an overarching summary (e.g., olive-black siliceous vitric mud) of the background lithology of each unit. However, most units contain not only the background sedimentation but also intercalated diverse components (e.g., ash beds, clasts, graded layers, etc.). All are described in detail in the complete lithologic descriptions as sedimentary structures (e.g., soft-sediment deformation and chaotic bedding) and features (e.g., mottling and ichnofacies).

4. Structural geology

4.1. X-ray computed tomography

XCT imaging provided real-time information, which was used to guide time-sensitive and whole-round core sampling during Expedition 405. The methods for collecting XCT imagery followed those in the measurement manual prepared for the Institute for Marine-Earth Exploration and Engineering (MarE3) by laboratory technicians from Marine Works Japan (3D X-ray CT Scanning, Version 3.00, 24 March 2015; based on GE Healthcare, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c; Mees et al., 2003; Nakano et al., 2000).

The XCT instrument on Chikyu is a Discovery CT 750HD (GE Medical Systems) capable of generating 16 cross-sectional images of the core at 0.625 mm spacing every 0.5 s, the time for one revolution of the X-ray source around the sample (Table T4). As a result of the high scanning rate, 1.5 m sections of core were typically imaged in 3 min. The imagery generated for each core consists of 512 × 512 pixel axis-normal images of X-ray attenuation values with 0.176 mm pixel resolutions. These data were stored as DICOM format files.

4.1.1. Background

The theory behind XCT has been well established through medical research and is briefly outlined in Carlson (2006). X-ray intensity (I) varies as a function of X-ray path length and the linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) of the target material:

- I = transmitted X-ray intensity,

- I0 = initial X-ray intensity,

- µ = LAC of the target material, and

- L = X-ray path length through the material.

LAC is a function of the chemical composition and density of the target material. The basic measure of attenuation, or radiodensity, is the CT number given in Hounsfield units (HU):

where µt is the LAC of the target material and µw is the LAC of water.

The distribution of attenuation values mapped to an individual slice comprises the raw data that are used for subsequent image processing. Successive 2D slices yield a representation of attenuation values in 3D pixels, referred to as voxels. Visualizations are generally accomplished by varying how the distribution of CT numbers is assigned to 256 shades of gray or a color palette. In general, high CT numbers correspond to bright colors in CT images, representing relatively high bulk density that may be caused by high density and/or an increase in elements with relatively higher atomic numbers (e.g., Fe). Shipboard analysis of CT images was done using both the Advantage Workstation (Lightspeed Ultra 16; General Electric Medical Systems) and the Horos 32-bit DICOM viewer running on a Macintosh computer (OSX 13.1).

Every 24 h during coring operations, an acrylic core mockup (calibration standard) was used to calibrate the XCT. The core mockup enables the calibration of the CT numbers for air (CT number = −1000), water (CT number = 0), and aluminum (2477 < CT number < 2487). For each calibration analysis, the CT number was determined for a 24.85 mm2 area at fixed coordinates near the center of the cylinder.

4.1.2. XCT scan data usage

XCT scans were used routinely during Expedition 405 throughout the core processing workflow for the following:

- To provide an assessment of core recovery and liner integrity for drilling operations,

- To inform and guide destructive whole-round sampling and provide an archival record of samples taken for whole-round sampling, and

- To support real-time lithologic and structural visual core description and structure measurement in the core description laboratory.

XCT scans were initiated immediately after core sections were cut so that ideal sections for time-sensitive whole-round samples could be identified using XCT imagery. In this way, all core sections were screened using 3D XCT imagery prior to whole-round sampling and core splitting to avoid destructive testing on sections of core that may contain key structural or sedimentary features necessary for core interpretation. This included identification of critically important intervals (e.g., thin principal slip zones and sequences of graded beds) that warranted detailed study and special handling during visual core description and sampling. Furthermore, collecting XCT imagery prior to whole-round sampling provided key archival data for all recovered core sections. The use of XCT screening also ensured that the selection of whole-round samples for shipboard and personal measurements included sections with minimal drilling disturbance and targeted relatively homogeneous representative sections of core for interstitial water (IW), mechanical properties, or microbiological analyses.

XCT imagery was used extensively throughout lithologic and structural visual core descriptions because many subtle or obscured features in split core faces may be easier to identify in XCT imagery. The reconstructed 3D XCT volumes were used to determine 3D geometries, crosscutting and other spatial relations, and orientation of primary and secondary structures. Fractures and other planar features that can be identified in the XCT scans can be oriented directly from the imagery by measuring the apparent dip and dip directions strike in various 2D sections (e.g., transverse, coronal, and sagittal) (Figure F8). Finally, XCT imagery was used to distinguish drilling-induced breccia from tectonic breccia.

4.2. Visual core description

We documented the preserved structures in the cores using VCDs and by measuring the apparent structure orientations on the working half of split core faces and whole cores (from the XCT images). Our methods and procedures follow those outlined in previous ODP, Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, and IODP expeditions (e.g., ODP Legs 131, 170, and 190; Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expeditions 315, 316, 319, 322, 333, 338, 343, and 348; and IODP Expeditions 358 and 370). We documented the primary and secondary structures observed by classifying structure type, determining the depth extent, measuring the orientation relative to the orientation of the core, and identifying and measuring any sense-of-slip indicators. These VCD data were hand logged onto a printed form at the core table, entered into an electronic spreadsheet, and entered into the J-CORES database using existing symbology. Where possible, the orientation data were also reoriented in the geographical coordinate system using shipboard discrete sample paleomagnetic declination and inclination information.

4.2.1. Core description and orientation data collection

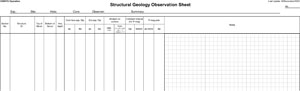

Each structure was recorded manually on a structural description sheet that was modified from similar tables used during Expedition 316 and subsequent expeditions (Figure F9). We used a plastic protractor for orientation measurements (Figure F10) and provided detailed observations, sketches, and core descriptions on the observation sheets. Using the working half of the split core provided greater flexibility to remove and cut (if necessary) pieces of the core for more careful study and measurement.

4.2.2. Orientation data analysis and true north correction

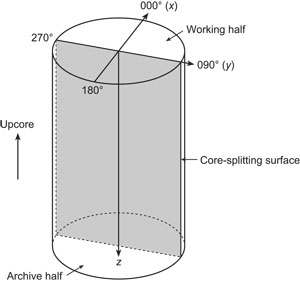

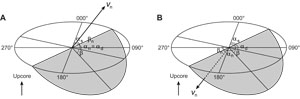

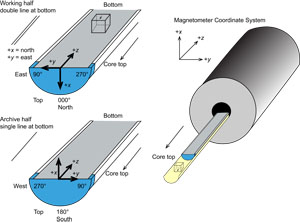

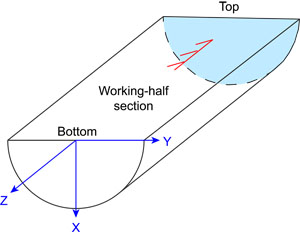

During Expedition 405, we adopted the spreadsheet template for orientation data calculation in the core reference frame (Figure F11). The core reference frame is such that the upcore direction is vertical upward, the core-splitting plane is 90°–270° and vertical, and the double line points toward 0° (Figure F8).

4.2.2.1. Calculation of plane orientation

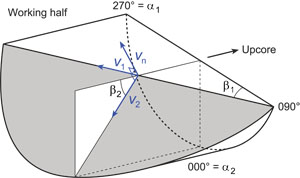

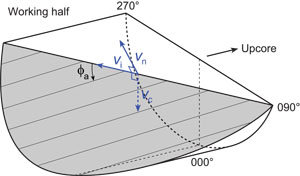

For planar structures (e.g., bedding or faults), two apparent dips on two different surfaces (e.g., one being the split core surface, which is 90°–270° and vertical, and the other being the horizontal or 0°–180° vertical surface) were measured in the core reference frame as trends (measured clockwise from 0°, looking down) and plunges. An xyz coordinate system was defined in such a way that the positive x-, y-, and z-directions coincide with 0°, 90°, and vertical downward, respectively (Figure F8). If the trends and plunges of the two apparent dips are given as (α1, β1) and (α2, β2), respectively, as in Figure F12, then the unit vectors representing these two lines (v1 and v2) are

The unit vector normal to this plane (vn) is then defined as follows:

The azimuth (αn) and plunge (βn) of vn are given by

The dip direction (αd) and dip angle (β) of this plane are αn and 90° + βn, respectively, when βn < 0° and αn ± 180° and 90° − βn, respectively, when βn ≥ 0° (Figure F13). The right-hand rule strike of this plane (αs) is then given by αd − 90°.

4.2.2.2. Calculation of slickenline rake

For a fault with slickenlines, the apparent rake angle of the slickenline (ϕa) is measured on the fault surface from either the 090° or 270° direction of the split core surface trace (Figure F14). The fault orientation was measured as described above. Provided that vn and vc are unit vectors normal to the fault and split core surfaces, respectively, the unit vector of this intersection line (vi) is perpendicular to both vn and vc and therefore defined as follows:

Knowing the right-hand rule strike of the fault plane (αs), the unit vector (vs) toward this direction is

The rake angle of the intersection line (ϕi) measured from the strike direction is given by

The rake angle of the slickenline (ϕ) from the strike direction is ϕi ± ϕa, depending on which direction the apparent rake was measured from and which direction the fault plane dips toward (Figure F15). ϕa should be subtracted from ϕi when the fault plane dips toward 270° and ϕa was measured from either the top or 090° direction or when the fault plane dips toward 90° and ϕa was measured from either the bottom or 090° direction. On the other hand, ϕa should be added to ϕi when the fault plane dips toward 90° and ϕa was measured from either the top or 270° direction or when the fault plane dips toward 270° and ϕa was measured from either the bottom or 270° direction.

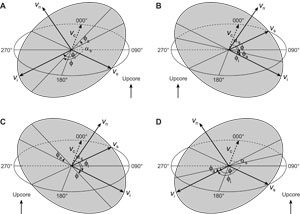

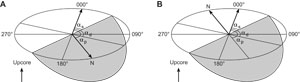

4.2.2.3. Azimuth correction based on paleomagnetic data

Discretely sampled paleomagnetic data were used where possible to correct drilling-induced rotations of the cored sediments. Provided that a core is vertical, its magnetization is primary, and a planar structure is horizontal (approximately <10°), the strike and dip direction of the plane can be rotated about a vertical axis in a geographic reference frame to restore it back to an in situ orientation. In a time of normal geomagnetic polarity, when the paleomagnetic inclination (βp) is ≥0°, the in situ strike (αs*) and in situ dip direction (αd*) of a plane in the geographic reference frame can be represented as the following (Figure F16A):

- αs = apparent strike,

- αd = apparent dip direction, and

- αp = direction of magnetic north (paleomagnetic declination).

When the geomagnetic polarity is reversed and the paleomagnetic inclination is βp < 0° (Figure F16B), the in situ strike and dip direction are represented as

If the structure is not approximately horizontal within the core, the plane must first be rotated back to horizontal (about a horizontal axis), thus rotating its paleomagnetic declination by the same degree with respect to the bedding plane, to obtain the original geographic orientation. The structure is then rotated around the vertical axis back to magnetic north. Each rotated structure must be contained within the same coherent interval in which the discrete paleomagnetic samples were taken.

4.2.3. Description and classification of structures

The VCD interface in the J-CORES database provides a compilation of the visual (macroscopic and/or microscopic) descriptions of core structures at a given section index and a record of planar structures in the core reference frame. In general, we described and classified the structures observed using the J-CORES and Expedition 316 terminology, which in turn is based on the J-DESC VCD scheme and ODP Legs 131, 156, 170, and 190 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1991, 1995b, 1997, 2001b). Terminologies were also kept consistent with Expedition 343 as much as possible to facilitate comparison. Below, we further clarify how individual primary and secondary structures are classified.

4.2.3.1. Primary structures

We measured the orientations of primary sedimentary structures, including (1) planar bedding, (2) chaotic and/or convolute bedding, (3) laminations, and (4) contacts. Bedding was defined by parallel, centimeter- to meter-scale layers of sediment that coincide with compositional layering, fining-upward sequences, and/or color banding. Chaotic and/or convolute bedding was noted where layering within a single sedimentary bed changed orientation within millimeter- to centimeter-scale lengths within cores and was often associated with small centimeter-scale folds and cobble- to boulder-sized block-in-matrix textures. Chaotic bedding was measured on fragments where a plane could be approximated. Laminations were defined where sequences of planar sedimentary layers were <1 cm thick. Contacts were measured where there was a well-defined planar boundary between lithologic variations that were not associated with secondary deformational structures.

4.2.3.2. Secondary structures

Secondary deformation-related structures are classified into six major categories:

- Major and minor faults with reverse, normal, or undetermined senses of slip;

- Fractures and fracture networks;

- Sediment-filled veins;

- Dark seams and dark seam networks;

- Scaly fabric; and

- Mineral veins.

4.2.3.3. Major faults

Major faults are defined by a local increase in the spatial density of deformation structures, a sharp change in bedding orientations, the presence of a major lithologic boundary, and/or a spatial correlation to intervals with distinct age reversals defined from biostratigraphy. Major faults are frequently co-located with centimeter- to tens of centimeters–thick intervals of fault rocks such as fault-related breccias, fault gouge, and/or scaly fabrics (described below). It may be difficult to distinguish natural faults from drilling-induced fractures. Helicoidal striated surfaces (i.e., polished surfaces showing striations that diverge outward) most likely indicate drilling-induced fracturing resulting from torque exerted by the bit on sediments. In contrast, faults that display more planar geometries, parallel lineations, and orientations that are compatible with preferred orientations displayed by multiple nearby faults are likely natural features. Lastly, when multiple orientation measurements are plotted in stereographic projection, natural minor faults are expected to display preferred orientations that may define coherent strain axes, whereas drilling-induced faults are expected to yield random orientation distributions or preferred orientation 60° from vertical.

In the Japan Trench, fault rocks generally include three types of deformed rocks: breccias, microbreccias, and fault gouge. Breccias are composed of fracture-bounded fragments that have clearly rotated with respect to each other. The presence of a matrix may be difficult to ascertain because of pervasive intrusion of incohesive material by drilling mud or washing away near the core surface by circulating fluids. Breccia fragments are typically more rounded than protobreccias, may have striated surfaces, and may contain opening incipient fractures. Microbreccias consist mainly of fragments of millimeters to <1 mm size. With increasing clay content and decreasing size of fragments, microbreccia can transition to fault gouge with a groundmass that is extremely fine grained compared to the visible clasts and grain size of the surrounding rocks, comprising 70% of the rock volume. The recognition of natural breccias and gouges in cores is important because it constitutes a straightforward means to locate fault zones and, more precisely, principal slip zones where strain reaches a maximum. This recognition, easily done in the field, is less trivial in cores, mainly because of frequent drilling- or splitting-induced brecciation and/or drilling-mud injection; both processes tend to produce structures that mimic natural products. During Expedition 405, the distinction between natural and induced breccias was based on a set of criteria that includes the following:

- Fragments observed in natural breccias commonly show polished or striated faces, whereas fragments in drilling-induced breccia commonly lack such features, except for spiral slickenlines (concentric circular slickenlines) that result from the rotational motion of the coring process.

- Fragments in natural breccias tend to be more rounded than those from drilling-induced breccias.

- Natural breccias are often bounded by and grade into less fractured rock, and the fracture fabrics in the bounding rocks display preferred orientations.

- Differential rotation of planar features is identified in XCT scans of drilling-induced breccias.

- Tectonic breccias show low contrast in XCT images between clasts and matrix with high XCT numbers, whereas XCT images of drilling-induced breccias are marked by spherical voids and bright clasts in a much darker matrix with low XCT numbers (Expedition 316 Scientists, 2009b).

4.2.3.4. Minor faults

We identify minor faults as planar structures that crosscut and truncate other structures on split core surfaces and XCT images and often have small subcentimeter-scale offsets. Minor faults are classified into three subcategories based on their sense of displacement: normal, reverse, and unidentified. The magnitude and sense of offset were measured, where possible (commonly in the XCT imagery), by reconstructing piercing points of bedding, fractures, or clasts or measuring striations along the fault plane surface.

4.2.3.5. Fracture and fracture networks

We generally labeled cracks as “fractures” when neither opening mode nor shear sense of motion (e.g., offset features, truncated bedding, striations, and presence of gouge) could be determined. Fracture networks were identified where multiple parallel and/or conjugate sets of crosscutting fractures produce zones of fragmented rock. The spacing and orientations of fractures in fracture networks may be highly variable.

4.2.3.6. Sediment-filled veins

Sediment-filled veins are identified as anastomosing structures that are vertically oriented and arranged in bed-perpendicular arrays with millimeter- to centimeter-scale intervein spacings. These sigmoidal, curviplanar veins are composed of denser material that appears bright on XCT images. The vein-filling material primarily consists of mud to clay-sized particles. Similar sediment-filled vein structures have been identified at other subduction zone settings within the accretionary prism, slope, and fore-arc basins of Nankai, Costa Rica, and offshore Oregon (Hanamura and Ogawa, 1993; Maltman et al., 1993; Shipboard Scientific Party, 2001a; Expedition 334 Scientists, 2012; Druitt et al., 2024). Analog experiments have shown that these structures may be related to earthquake shaking (Brothers et al., 1996).

4.2.3.7. Dark seams and dark seam networks

Dark seams are identified as individual black curviplanar structures that are commonly <1 mm thick. Although dark seams have low color contrast to the darker sediments that form in the Japan Trench prism, they are easily identifiable from XCT images because of their higher density compared to surrounding sediments, which suggests that they may be related to a localized reduction in porosity through compaction (Fossen et al., 2007; Kirkpatrick et al., 2015). Similarly, dark seam networks are identified as high-density zones of dark seams, where many anastomosing dark seams may form curviplanar web-like zones, ranging in width from 1 to 10 mm, and appear as distinctly bright features in XCT images. Our classification of dark seam networks is structurally similar to deformation bands, which have been widely documented at subducting margins globally, including the Nankai Trough (e.g., Maltman et al., 1993; Maltman, 1998; Ujiie et al., 2004; Conin et al., 2014), Chile (Rochford et al., 1995), and Costa Rica (Vannucchi and Tobin, 2000). However, the mechanisms of formation of the dark seams remain poorly constrained.

4.2.3.8. Scaly fabrics

Scaly fabric occurs in foliated clay-rich rocks with an anastomosing network of curviplanar, striated shear surfaces. The intensity of the fabric is generally a function of several parameters, including but not limited to strain, sediment composition, and compaction (Vannucchi et al., 2003). Clay-rich beds or clay-rich matrix material in breccia may contain a scaly fabric, which is included in the descriptions to indicate evidence of shear strain. Scaly fabrics often consist of millimeter- to centimeter-scale angular to subrounded fragments or phacoids with little to no matrix in between. Fragment surfaces may be polished or striated. These deformation characteristics are similar to the phacoids identified in the plate boundary fault in the Nankai, off shore the Muroto Peninsula, Japan (Morgan and Karig, 1995; Ujiie et al., 2003).

4.2.3.9. Mineral veins

Abundant mineral veins were identified in cores recovered from basaltic compositions, and less commonly, veins were also identified in sediments and sedimentary rocks. For all observed veins, we note the width, composition, and orientation of each structure. We also note if there is evidence for multiple stages of vein formation using the interpretation of crosscutting relationships or variation in mineral compositions.

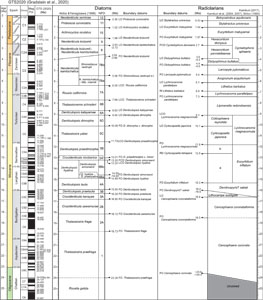

5. Biostratigraphy

5.1. Timescale/Chronological framework

During Expedition 405, diatoms and radiolarians were studied to assess biostratigraphic age and environmental constraints of the sedimentary sections at Sites C0019 and C0026. Shipboard biostratigraphic age assignments were principally based on the analysis of core catcher samples. Where appropriate, additional samples from split core sections were analyzed, mostly as smear slides for diatoms and as acid clean slides for radiolarians, to refine biostratigraphic boundaries, examine critical intervals, or work with the lithostratigraphy and structural geology teams to analyze sedimentary clasts or investigate significant lithologic transitions including faults.