Kodaira, S., Conin, M., Fulton, P., Kirkpatrick, J., Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., and the Expedition 405 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 405

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.405.104.2025

Site C00261

![]() M. Conin,

M. Conin,

![]() J. Kirkpatrick,

J. Kirkpatrick,

![]() C. Regalla,

C. Regalla,

![]() K. Ujiie,

K. Ujiie,

![]() P. Fulton,

P. Fulton,

![]() S. Kodaira,

S. Kodaira,

![]() N. Okutsu,

N. Okutsu,

![]() L. Maeda,

L. Maeda,

![]() S. Toczko,

S. Toczko,

![]() N. Eguchi,

N. Eguchi,

![]() P. Bellanova,

P. Bellanova,

![]() C. Brown,

C. Brown,

![]() M. Brunet,

M. Brunet,

![]() M. Castillo,

M. Castillo,

![]() Y.-C. Chang,

Y.-C. Chang,

![]() M.-L. Doan,

M.-L. Doan,

![]() J. Everard,

J. Everard,

![]() A. Fintel,

A. Fintel,

![]() J. Ford,

J. Ford,

![]() R. Fukuchi,

R. Fukuchi,

![]() A. Gough,

A. Gough,

![]() H. Guo,

H. Guo,

![]() D. Gürer,

D. Gürer,

![]() R. Hackney,

R. Hackney,

![]() M. Hagino,

M. Hagino,

![]() Y. Hamada,

Y. Hamada,

![]() H. Hosono,

H. Hosono,

![]() A. Ijiri,

A. Ijiri,

![]() M. Ikari,

M. Ikari,

![]() T. Ishikawa,

T. Ishikawa,

![]() M. Iwai,

M. Iwai,

![]() T. Jeppson,

T. Jeppson,

![]() M.-J. Jurado,

M.-J. Jurado,

![]() N. Kamiya,

N. Kamiya,

![]() T. Kanamatsu,

T. Kanamatsu,

![]() A. LaPlante,

A. LaPlante,

![]() W. Lin,

W. Lin,

![]() A. Miyakawa,

A. Miyakawa,

![]() Y. Morono,

Y. Morono,

![]() Y. Nakamura,

Y. Nakamura,

![]() U. Nicholson,

U. Nicholson,

![]() H. Okuda,

H. Okuda,

![]() P. Pei,

P. Pei,

![]() C. Pizer,

C. Pizer,

![]() T. Rasbury,

T. Rasbury,

![]() R.V.M. Robertson,

R.V.M. Robertson,

![]() C. Ross,

C. Ross,

![]() S. Satolli,

S. Satolli,

![]() H. Savage,

H. Savage,

![]() K. Schaible,

K. Schaible,

![]() S. Shreedharan,

S. Shreedharan,

![]() H. Sone,

H. Sone,

![]() C. Sun,

C. Turel,

C. Sun,

C. Turel,

![]() T. Uchida,

T. Uchida,

![]() A. Yamaguchi,

A. Yamaguchi,

![]() Y. Yamamoto,

Y. Yamamoto,

![]() T. Yoshimoto,

T. Yoshimoto,

![]() J. Zhang,

A. Wspanialy,

J. Zhang,

A. Wspanialy,

![]() E. Le Ber,

E. Le Ber,

![]() M.B. Rydzy, and

N. Schuba2

M.B. Rydzy, and

N. Schuba2

1 Conin, M., Kirkpatrick, J., Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Fulton, P., Kodaira, S., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., Bellanova, P., Brown, C., Brunet, M., Castillo, M., Chang, Y.-C., Doan, M.-L., Everard, J., Fintel, A., Ford, J., Fukuchi, R., Gough, A., Guo, H., Gürer, D., Hackney, R., Hagino, M., Hamada, Y., Hosono, H., Ijiri, A., Ikari, M., Ishikawa, T., Iwai, M., Jeppson, T., Jurado, M.-J., Kamiya, N., Kanamatsu, T., LaPlante, A., Lin, W., Miyakawa, A., Morono, Y., Nakamura, Y., Nicholson, U., Okuda, H., Pei, P., Pizer, C., Rasbury, T., Robertson, R.V.M., Ross, C., Satolli, S., Savage, H., Schaible, K., Shreedharan, S., Sone, H., Sun, C., Turel, C., Uchida, T., Yamaguchi, A., Yamamoto, Y., Yoshimoto, T., Zhang, J., Wspanialy, A., Le Ber, E., Rydzy, M.B., and Schuba, N., 2025. Site C0026. In Kodaira, S., Conin, M., Fulton, P., Kirkpatrick, J., Regalla, C., Ujiie, K., Okutsu, N., Maeda, L., Toczko, S., Eguchi, N., and the Expedition 405 Scientists, Tracking Tsunamigenic Slip Across the Japan Trench (JTRACK). Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 405: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.405.104.2025

2 Expedition 405 Scientists' affiliations.

1. Background and objectives

1.1. Objectives

The primary drilling objective at Site C0026 was to characterize the complete section of the Pacific plate sedimentary rocks and underlying uppermost basement, which are inputs to the subduction zone, using a combination of logging-while-drilling (LWD) measurements and coring. The composition, spatial distribution, and thickness of the sedimentary rocks that reside on the oceanic plate outboard of the trench at a subduction zone are thought to be key controls on the seismogenic behavior of the subduction megathrust, as well as on the long-term evolution of the subduction forearc (e.g., Underwood, 2007). For example, the composition and burial history of sedimentary rocks determines rock mechanical properties such as the frictional strength and cohesion of the rocks, hydrologic properties such as rock porosity and permeability, and the mineral-bound water content, which determines the fluid budget for dehydration reactions during diagenesis and metamorphism. These parameters dictate the overall strength of the sedimentary rocks, so they influence the propagation of the megathrust through the input section. After the input section is subducted, they also dictate the frictional stability of the fault and how it changes with depth. Identifying the input sedimentary rocks and measuring their thicknesses is therefore an important step in understanding the factors that control the magnitude of shallow earthquake slip on subduction zones.

The nearest reference drilling site on the Pacific plate is Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) Leg 56 Site 436 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980), which is located >250 km north-northeast of Site C0026 (see Figure F1 in the Expedition 405 summary chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025b]). Previous comparison of cores recovered from Site 436 provided the basis for interpreting the origin of lithostratigraphic units at Site C0019 (e.g., Rabinowitz et al., 2015). These results indicate Late Miocene to Cretaceous pelagic clay in the input section is a mechanically weak layer that localizes the plate boundary deformation (Chester et al., 2013; Kameda et al., 2015). They also provided insight into the complexity in the plate boundary fault by revealing stratigraphic age reversals in the mudstones that are intercalated within the fault zone (Rabinowitz et al., 2015). However, recovery during Leg 56 was incomplete, and there is known variation in the thickness of the layers of sedimentary rocks on the Pacific plate along the Japan Trench (Nakamura et al., 2023). Furthermore, recent results from International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 386 document Pleistocene to Holocene stratigraphic sequences in basins along the Japan Trench, which indicates there may be stratigraphically equivalent sediments seaward of the trench (Strasser et al., 2023). Site C0026 therefore provides a reference section closer to the location of Site C0019 that can reduce uncertainty in the initial interpretations of Site C0019, provides constraints on the regional-scale variability of the mechanical and hydrologic properties of input material, and additionally facilitates comparisons with the nearby sedimentary records from the trench-fill basins.

1.2. Background

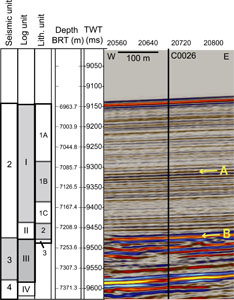

1.2.1. Geologic setting

Site C0026 is located on the Pacific plate ~8 km east of the Japan Trench and approximately 14 km east of Site C0019 (37°55.6′N, 144°04.1′E at a water depth of 6945 m) (Figure F1). The seafloor at this location is a broadly flat plain cut by numerous fault scarps, which are interpreted to be faults accommodating extension associated with flexure at the outer rise. The site was chosen because it is situated between seismically resolvable normal faults that offset sedimentary and volcanic rocks and the seafloor (Figure F2). High-resolution multichannel seismic reflection profile data indicate that the stratigraphy at Site C0026 is not disrupted by this faulting. Based on the interpreted seismic sections, the stratigraphy at Sites C0026 and C0019 was classified into four major seismic units (SU1–SU4) (following Nakamura et al., 2013). The uppermost unit (SU1) is restricted to the landward trench slope and is absent from Site C0026. At Site C0026, the uppermost unit we expected to penetrate was Unit SU2, which is characterized by generally well stratified, parallel, and laterally continuous reflections with relatively weak seismic amplitude. Locally, Unit SU2 shows small-scale internal deformation, and it regionally shows large-scale offset by horst and graben normal faults. Unit SU2 is also intensely deformed in the vicinity of the trench axis. Unit SU2 correlates with hemipelagic/pelagic mud/mudstone and basal pelagic clay recovered at Site 436. Unit SU3 directly underlies Unit SU2 and is characterized by relatively strong reflections with one continuous reflector at the top, all of which are parallel to those of Unit SU2. The base of Unit SU3 is marked by a high-amplitude semicontinuous reflection. In comparison with the stratigraphy at Site 436, Unit SU3 is interpreted to be Cretaceous chert. The lowermost unit (SU4) is the basement, which is interpreted to be the Mesozoic mafic volcanic and igneous crust of the Pacific plate.

1.2.2. Motivation for hole positioning

Hole C0026A was drilled to collect LWD measurements with the goal of characterizing the entire input section from the seafloor to oceanic crust (Figure F1). The motivation for collecting LWD data from Hole C0026A was to fingerprint the lithostratigraphic units with LWD tools to derive primary formation characteristics (composition, density, etc.) and thermal and physical properties and to facilitate the interpretation of the logs at Site C0019. Because of operational problems, only real-time data could be obtained from this hole.

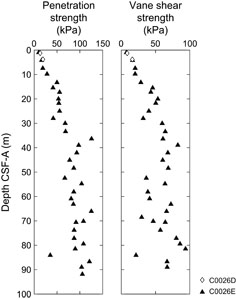

Hole C0026B was drilled with the small diameter rotary core barrel (SD-RCB) system to a total depth of 290.0 meters below seafloor (mbsf). Cores were collected to sample the input section, enable characterization of the lithostratigraphic units, and facilitate comparison with Sites 436 and C0019. Holes C0026C–C0026E were drilled with the hydraulic piston coring system (HPCS) to 6.5, 16.0, and 92 mbsf, respectively, which targeted the sediments at and immediately beneath the seafloor. Formation temperature measurements were taken in Hole C0026E using the advanced piston corer temperature (APCT-3) system. Priorities for postexpedition analysis of cores include but are not limited to measuring the mechanical, elastic, frictional, and hydrological properties of the incoming sedimentary units; establishing constraints on the chronology of the input stratigraphy; and evaluating the potential for sediments distal to the trench to record evidence for past earthquake activity.

2. Operations

The overall operations at Site C0026 are summarized in Table T1.

2.1. Hole C0026A

The vessel moved from Site C0019 to Hole C0026A by 2115 h on 22 September 2024 and completed preparations for dynamic positioning, such as transponder deployments, calibration, and field arrival check, at 0945 h on 23 September.

The LWD bottom-hole assembly (BHA) was made up with a new drill bit but with the same LWD tools used for Site C0019 operations. It started running at 0945 h. LWD signal tests were performed at 508.0, 2023.0, 5043.0, and 6868.0 m below rotary table (BRT) while running. The underwater TV (UWTV) camera system was run down to 8 m above the drill bit at 2100 h on 24 September for the seabed survey. The seabed survey was conducted for all planned LWD and coring holes, and it confirmed the water depth for each hole by tagging the seafloor with the drill string. The LWD BHA was spudded into Hole C0026A at 6957.0 m BRT at 0019 h on 25 September (see Table T1 in the Expedition 405 summary chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2005b]). We washed down from 6957.0 to 7047.0 m BRT (0–90.0 mbsf) without rotation because the first LWD hole of Site C0026 was planned as a deep hole. Drilling started at 1030 h after the UWTV was recovered to the surface and continued to 7405.0 m BRT (448.0 mbsf) at 2200 h on 27 September, with the rate of penetration (ROP) averaging 10–30 m/h.

High torque and stalled pipe were observed, and the drill string got stuck at 7401 m BRT just after connecting a new drill pipe stand. A total of 10 m3 of seawater gel (SWG) was pumped, followed by multiple attempts to free the drill string until 1000 h on 29 September:

- Overpull of 300 kN observed >45 times while pumping 590 gal/min × 22 MPa;

- Overpull of 500 kN observed >9 times while pumping 590 gal/min × 22 MPa and 20 kN while pumping 590 gal/min × 22 MPa;

- Sweeping 10 m3 of SWG with 716 gal/min × 71.9 MPa;

- Jarring down and applying slack off weight 400 kN >15 times; 900 kN overpull and attempt jarring up 15 times without pumping (fire only one time on the fifth attempt);

- 1250 kN overpull and attempt jarring up >100 times while pumping 7 m3 of kill mud with 600 gal/min × 26.5 MPa; and

- Pumping 7 and 10 m3 of SWG with 600 gal/min × 23 MPa; 1400 kN overpull and attempt jarring up >10 times without pumping.

Because all attempts failed to free the drill string, the final decision to abandon Hole C0026A and LWD operations was made at 1000 h on 29 September. The drill string was severed by a Colliding Tool at 1845 h on 30 September and recovered to the surface at 1145 h on 1 October.

The vessel sailed to an evaluation point soon after recovery of the drill string because of Typhoon 17 (JEBI).

2.2. Hole C0026B

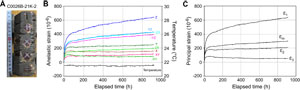

The vessel returned to Site C0026 from Site C0019 at 1200 h on 31 October 2024. The SD-RCB BHA was run in the hole and spudded into Hole C0026B, which lies ~30 m south of Hole C0026A, at 1158 h on 1 November without the use of the UWTV. The center bit was recovered after washing down from 6956.0 to 7036.0 m BRT (0–80.0 mbsf) at 2215 h. Coring began at 2215 h and continued until 1915 h on 6 November. The coring advance was kept at 9.5 or 10 m for Cores 405-C0026B-1K through 15K and then varied between 3.0 and 7.0 m because of observed standpipe pressure increases to improve the chance of successfully coring fragile formations. In total, 32 cores (total length of initial recovery = 101.87 m) were collected from 80.0 to 290.0 mbsf (210.0 m interval) with an average recovery of 48.5% (Table T2). The SD-RCB BHA was pulled out to the surface at 1400 h on 7 November.

2.3. Hole C0026C

A HPCS BHA was made up and run in the hole at 2330 h on 7 November 2024 and spudded into Hole C0026C at 6957.0 m BRT at 1946 h without the UWTV. Core 1H was recovered on deck at 2100 h (Table T2) and successfully collected the surface sediments and mudline with some bottom water. The HPCS BHA was kept in the water while the ship moved to the next hole.

2.4. Hole C0026D

At 2159 h on 8 November 2024, Hole C0026D was spudded in from the same height and location as Hole C0026C (Table T2), again without the UWTV. Core 1H was recovered on deck at 2315 h and found to have successfully collected the surface sediment and mudline, but the bottom water flowed out and was lost when the core barrel was laid down. After cutting the second core, drilling down was required to pull the core barrel out. The sinker bar was recovered but failed to recover the core barrel because of shearing between the sinker bar and the coring line running tool. Attempts were made to recover the core barrel using the backup coring line, and the upper section of the core barrel was recovered. Hole C0026D was abandoned at 0915 h on 9 November because the lower part of the core barrel remained lost in the hole.

2.5. Hole C0026E

Spud-in of Hole C0026E was conducted at 1035 h on 9 November 2024 at the same height and location as Holes C0026C and C0026D without the UWTV. Core 405-C0026E-1H also collected the surface sediment and mudline with the bottom water. Coring continued with full stroke and required the drawworks assist to help pull the inner barrel out for all cores. In total, 10 cores (total length of initial recovery = 92.94 m) were collected from 0 to 92.0 mbsf (92.0 m interval) with an average recovery of 101.0% (Table T3).

The vessel moved back to Site C0019 after the HPCS BHA was pulled out of the hole to the surface at 1545 h on 11 November.

3. Logging while drilling

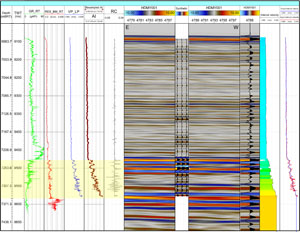

One hole was drilled and logged at Site C0026: Hole C0026A. Logging data were acquired using a LWD/measurement-while-drilling (MWD) assembly consisting of the SLB TeleScope, MicroScope, and SonicScope tools. Hole C0026A was drilled to a maximum depth of 7405.0 m BRT (448.0 mbsf). MWD data were transmitted in real time with a limited set of LWD data through the drilling fluid telemetry system. See Introduction and Logging while drilling, both in the Expedition 405 methods chapter (Kirkpatrick et al., 2025a), for a detailed description of the operations and tools. The LWD tools were not able to be recovered, so no memory data are available for Hole C0026A.

3.1. Depth shift

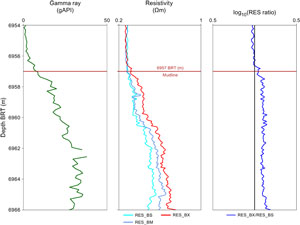

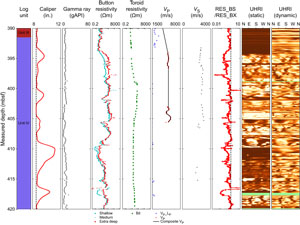

The mudline (seafloor) was identified from the midpoint of the first break in the gamma ray and resistivity logs (Figure F3). A mudline was picked at 6957.0 m BRT in Hole C0026A. All LWD data were converted to the LWD depth below seafloor (LSF) depth scale. In this section, LSF depths are referred to as meters below seafloor (mbsf) based on the mudline depth.

3.2. Data and log quality

3.2.1. Drilling parameters

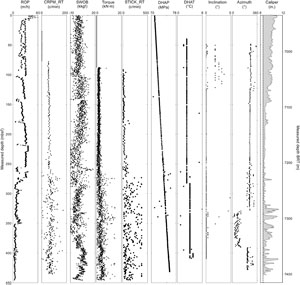

Figure F4 shows the overview of the QC logs, such as drilling parameters and frequency of stick-and-slip. Caliper has been estimated from the resistivity data by the contractor. The uppermost ~275 m was drilled smoothly, with no significant drilling issues. MWD/LWD data quality was good for the upper section, with good quality real-time data from all tools. The interval from 275 mbsf to the total depth was affected by significantly more challenging drilling conditions. The average ROP was ~30 m/h to ~275 mbsf, ~10 m/h to ~350 mbsf, and <5 m/h in the deepest section of the hole. The inclination of the borehole was near vertical, with some spurious spikes in the inclination log. The real-time resistivity borehole images were of moderate to poor quality with broad drilling disturbance and intervals with missing to spotty transmission (e.g., ~246–361 mbsf) (Figure F5). The borehole is significantly enlarged at about 150 mbsf but stays in gage to 315 mbsf. Below this depth, caliper significantly degrades.

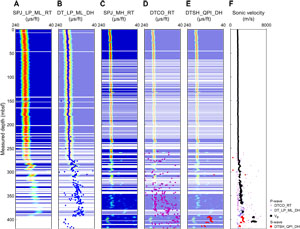

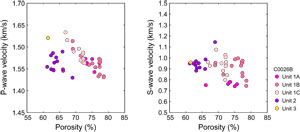

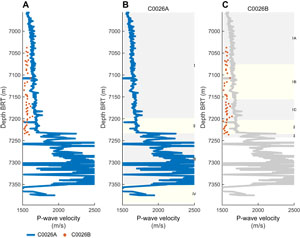

3.2.2. Sonic data

Sonic velocities are provided through four channels in the final dataset delivered by the contractor: a leaky P-wave slowness (DT_LP_ML_DH) picked from low-frequency monopole data (using the coherence plot SPJ_LP_ML_RT), a VP slowness (DTCO_RT) determined from high-frequency monopole data (using the coherence plot SPJ_MH_RT), a shear sonic slowness (DTSH_QPI_DH in μs/ft), and synthetic VP data. Any velocity (V) in meters per second can be computed from the corresponding slowness (DT) with the formula V = 304800/DT. Figure F6 compares these sonic datasets and provides QC plots.

Two QC data are provided by the contractor: slowness-time plane projection for the high-frequency signal of the monopole (SPJ_MH_RT) and for the low-frequency signal of the monopole (SPJ_LP_ML_RT). No plots for slowness-frequency analysis was provided because of the low transmission rate of mud-pulse telemetry. The SPJ_LP_ML_RT coherence signal is strong to 315 mbsf. Below 315 mbsf, a moderate intensity coherence is observed at the same slowness that vanished below 393 mbsf. Leaky P velocity (VP_LP) is in good agreement with the SPJ_LP_ML_RT signal. High-frequency monopole data provide additional information. The SPJ_MH_RT coherency plot is strong down to 275 mbsf, but no DTCO_RT data were picked in this interval. Below this depth, a less coherent signal can be identified, but its intensity corresponds to very low velocities (~1600 m/s). SPJ_MH_RT coherency further decays below 325 mbsf, corresponding to scattered DTCO_RT pickings. Three intervals have high coherence in SPJ_MH_RT: 382–386, 394–396, and 403–405 mbsf. In these intervals, P-wave velocities are estimated at ~2720 m/s, ~5150 m/s, and ~5250 m/s, respectively. Below 405 mbsf, the coherency signal becomes strong again but corresponds to very low velocities (~1500 m/s). The final VP delivered by the contractor is based on the low-frequency monopole data down to 368 mbsf. Below that depth, the final VP data correspond to the high-frequency monopole pickings. The formation between ~276 and ~393 mbsf is interpreted to be chert, and the formation below is interpreted to be basalt based on the comparison to the seismic units defined from high-resolution seismic surveys prior to Expedition 405 (Nakamura et al., 2013). This is the same sequence as at the bottom of Site C0019 or at DSDP Site 436 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980).

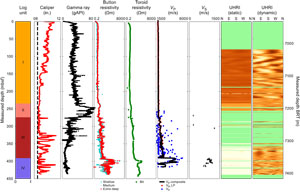

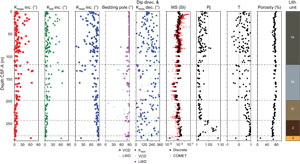

3.3. Logging units

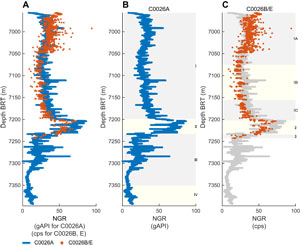

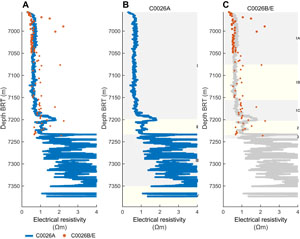

The combination of different MWD/LWD measurements, particularly the gamma ray, resistivity, and sonic logs, allowed us to define four logging units (I–IV) (Figure F5).

3.3.1. Logging Unit I (0–241.90 mbsf)

Unit I is characterized by moderate gamma ray values ranging ~20–45 gAPI, very low resistivity values (typically <1 Ωm), and low VP values (<1700 m/s). Gamma ray, resistivity, and sonic velocity values are relatively consistent with only minor excursions from this range, suggesting that the lithology is similar throughout. Both VP and resistivity values increase slightly downhole to 2010 m/s and 1.5 Ωm, respectively. This is consistent with a burial compaction trend for relatively unlithified sediments. The log values are consistent with those of siliceous mudstone, as observed in the equivalent shallow sequences during DSDP Leg 56 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980) and Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 343 (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013).

3.3.2. Logging Unit II (241.90–276.30 mbsf)

Unit II is characterized by high gamma ray values with an average of ~60 gAPI and a gradual downhole decrease in resistivity values from ~2 to 1 Ωm. Gamma ray values reach a peak of 87 gAPI near the top of the sequence at 245 mbsf, and, overall, values slightly decline farther downhole. The overall pattern of gamma ray and resistivity is consistent with the pelagic clay observed in the equivalent interval from Leg 56 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980), Unit III in Hole C0019B from Expedition 343 (Expedition 343/343T Scientists, 2013), and cores from Hole C0026B (see Lithostratigraphy).

3.3.3. Logging Unit III (276.30–393.60 mbsf)

The top of Unit III is characterized by a sharp decrease in gamma ray values and a significant increase in resistivity log responses. Gamma ray values for this unit are consistently lower than in the units above. They have an average value of 18 gAPI between 275 and 355 mbsf. There is a notable decrease in gamma ray at 356 mbsf and average values of 8 gAPI to the base of the unit. Resistivity values are variable in this unit, from 1 to 10 Ωm, with greater separation between shallow (channel RES_BS) and extra deep resistivity (channel RES_BX) in the deeper section, but the values are higher than those of Unit I. This alternation between high and low resistivity values is compatible with chert lithology, as observed at Site C0019 (see Logging while drilling in the Site C0019 chapter [Regalla et al., 2025]). The real-time velocity data for this section are relatively scattered, particularly for high-frequency P-wave slowness, which appears to be unreliable. VP values increase within this interval from 1760 to 2830 m/s, consistent with values observed in the equivalent interval (Unit IV) at Site C0019. The resistivity borehole images in the upper section of Unit III are extremely poor between 276 and 361 mbsf.

3.3.4. Logging Unit IV (393.60–435.0 mbsf)

The top of Unit IV is characterized by a sharp increase in resistivity values from around 2 to ~100 Ωm (Figure F7). In two intervals (394–396 and 403–405 mbsf), P-wave velocity could be measured at 5150 and 5250 m/s, respectively. S-wave velocities could also be recorded in this interval at ~3030 m/s. Resistivity values vary significantly in this interval, ranging 1–100 Ωm and exhibiting varying degrees of separation between shallow and extra deep resistivity. Resistivity images (real time) are of generally poor quality but indicate nonplanar features, possibly fractures and/or cooling-related structures, similar to the images observed at the bottom of Hole C0019H in a unit interpreted to be basalt (see Logging while drilling in the Site C0019 chapter [Regalla et al., 2025]). Gamma ray values are comparable to those in Unit III, with consistent values of around 8 gAPI between ~360 and 400 mbsf but more variable (ranging 3–20 gAPI) below 400 mbsf. These values are consistent with those expected for altered basalt or interbedded basalt and sedimentary rocks.

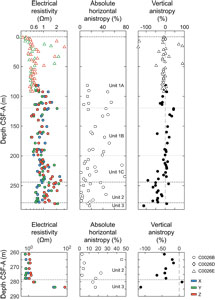

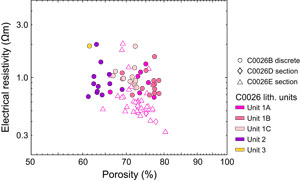

3.4. Physical properties

The LWD data provide information on the natural radioactivity (gamma ray) and electrical resistivity (button and toroid velocities) and an estimate of P-wave velocity. Because only real-time data were available, the data are sparse and irregularly sampled.

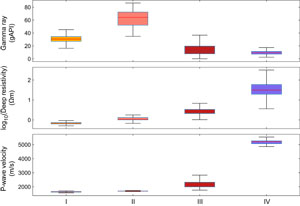

3.4.1. Statistics of physical properties

Table T4 and Figure F8 summarize the variability in the main physical properties observed for Hole C0026A. There are strong petrophysical contrasts along the borehole, for which the mean and the standard deviation are reported. The extra deep resistivity (RES_BX) is considered close to the true resistivity of the formation because of the similarity between RES_BX and the medium resistivity (RES_BM).

The gamma ray values in Unit I are moderate at 31 ± 6 gAPI, which contrasts with the larger values in Unit II (60 ± 2 gAPI) and the very low values in Units III (15 ± 8 gAPI) and IV (8 ± 3 gAPI).

The other physical parameters increase with depth. Electrical resistivity increases from very low values of 0.7 ± 0.1 Ωm in Unit I to low values in Unit II (1.1 ± 0.3 Ωm). Resistivity increases faster in Unit III (2.8 ± 1.1 Ωm) and steps up in Unit IV, where electrical resistivity increases by an order of magnitude to reach 57 ± 9 Ωm.

VP velocities follow a pattern similar to electrical resistivity with a gradual increase in Units I (1640 ± 30 m/s) and II (1700 ± 10 m/s), a faster increase in Unit III (2170 ± 230 m/s), and a step to large values in Unit IV (5030 ± 260 m/s).

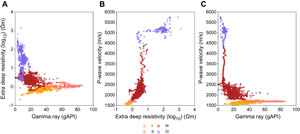

3.4.2. Relations between physical properties

Figure F9 shows crossplots between the main physical properties (gamma ray, VP, and electrical resistivity).

Figure F9A compares electrical resistivity to gamma ray. In this crossplot, Unit I has a moderate gamma ray and the smallest resistivity. Unit II is distinct in its high gamma ray values. Units III and IV contain less radioactive elements, but Unit IV is distinctive in its higher resistivity.

Figure F9B shows a positive correlation between resistivity and P-wave velocity, which is particularly strong for Units I–III. Unit IV is characterized as a high-velocity zone with a positive correlation between the two properties, but the variability is larger because of the large variability in P-wave velocity (Figure F8).

The crossplot between P-wave velocity and gamma ray (Figure F9C) also shows the difference between the four units. Unit I has a moderate gamma ray and small VP. Unit II has low velocity but high gamma ray. Unit III values cluster around low gamma ray and moderate VP, whereas Unit IV has distinctive low gamma ray and in places very large VP.

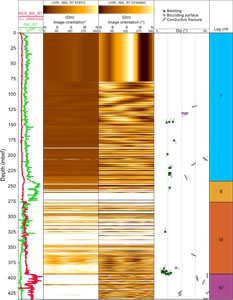

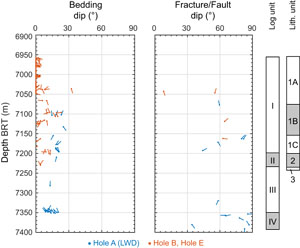

3.4.3. Resistivity image interpretation

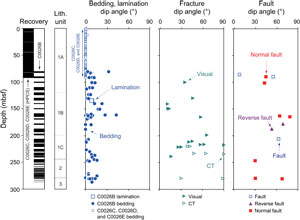

Real-time ultrahigh-resolution images (UHRIs) are available between 79 and 438 mbsf at low resolution from the real-time transmission through the drilling fluid telemetry system. The overall image quality is fair to poor for Hole C0026A. Some geologic features (bedding and fractures) and wellbore failures (breakouts) were identified from the images. However, all features identified in Hole C0026A are of fair quality only because of the low resolution of the images, which limits the possibility of identifying individual features. Image artifacts and missing sections are common throughout the image logs, which hinders interpretation. Between 79 and 145 mbsf, the image quality is poor because of artifacts that may result from tool orbiting, where the tool scrapes diagonally along the borehole wall (Lofts and Bourke, 1999). These diagonal artifacts are less pronounced between 145 and 187 mbsf, resulting in moderate image quality. Horizontal image artifacts are common throughout the entire imaged interval and are thought to be related to the stick and slip of the MicroScope tool as the buttons rotate (Lofts and Bourke, 1999). Image quality between 246 and 361 mbsf is extremely poor with significant data gaps. The interval 361–438 mbsf has improved image quality. All images were oriented to north, and the inclination of the hole was accounted for using continuous MWD data (Figure F4). Geologic features were identified and characterized, and true orientations were reported. Shallow, medium, deep, and extra deep resistivity images are unavailable for Hole C0026A because the memory data were not recovered.

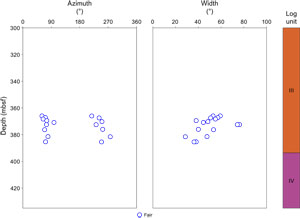

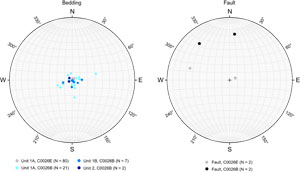

3.4.4. Bedding and fractures

Structural and sedimentary features were identified and interpreted using the low-resolution real-time UHRIs (Figure F10). Each pick was critically examined by three simultaneous observers to confirm (1) sinusoids on the unwrapped images of the cylindrical borehole wall and (2) consistent criteria for structural and bedding interpretation. Our interpretation was guided by the structural picks in Hole C0019H (see Logging while drilling in the Site C0019 chapter [Regalla et al., 2025]), for which high-resolution memory images are available. Features in the logs were divided into three categories: bedding, conductive or resistive fracture, and bounding surface:

- Bedding: a series of sinusoids with consistent orientation and resistivity signatures that are visible from the static and dynamic UHRIs. The sinusoid can be traced over the full image width (see Figure F23 in the Site C0019 chapter [Regalla et al., 2025]).

- Conductive/Resistive fracture: a planar feature, visible as a sinusoid in the flattened image, that may or may not host shear displacement. Its orientation crosscuts the orientation of nearby bedding. We note whether the fracture is predominantly resistive or conductive.

- Bounding surface/feature: when a crosscutting relationship is not evident but a planar discontinuity or distinctive change in resistivity (i.e., more conductive to less conductive across a sinusoidal feature) is clear, we note the feature as a bounding surface. This may be indicative of a change in bulk rock properties (e.g., the bounding surface may be an unconformity, a fault/fracture aligned with adjacent bedding, or a fracture), especially in Unit IV, which was interpreted to be basalt.

All bedding identified in Hole C0026A is low angle, with an average dip of 16° ± 4° (Table T5). Bedding orientation in Unit I varies in what is interpreted to be relatively unlithified sediments. However, accurately determining the orientation of subhorizontal features in the low-resolution logs is particularly challenging, which may lead to significant uncertainty in the bedding orientation measurements and, potentially, bias toward higher dip angles. High-angle conductive fractures are identified in Unit I with dips between 44° and 80°. Bedding identified in Unit III dips shallowly northwest, which is consistent with the dip of reflections in the nearby seismic data (see Core-log-seismic integration).

The five bounding surfaces identified in Hole C0026A are structures that may indicate fractures formed along weakened bedding planes or represent a change in bulk rock properties (Figure F10). However, we did not classify these features as either bedding or fractures because there were no observed crosscutting relationships with adjacent bedding planes.

The UHRIs in Unit IV, interpreted to be basalt or mixed basalt and sedimentary rocks, are highly resistive with a chaotic behavior of nonplanar conductive features that cut vertically and horizontally across the unwrapped resistivity image (Figure F10). One bounding surface and seven conductive fractures are identified in Unit IV; however, we are unable to distinguish if these features are related to tectonic deformation, cooling, or basalt characteristics. The conductive fractures are predominantly high angle and dip east, which is consistent with the orientation of conductive fractures identified in Hole C0019H in Unit V.

3.4.5. Wellbore failure

In Hole C0026A, LWD images show distinct conductive tracks approximately 180° apart that are consistent with borehole breakouts (Figure F10; Table T6) (Zoback, 2007). Breakouts occur between 365 and 385 mbsf in Unit III. Poor image quality and artifacts in the real-time images result in uncertain breakout picks. A quality code of "fair" is assigned to all breakout picks in Hole C0026A, following the criteria outlined for Site C0019 (see Logging while drilling in the Site C0019 chapter [Regalla et al., 2025]). Identified breakouts are frequently overprinted by horizontal image artifacts, and both tracks are not always visible at the depths picked. A total of 16 breakouts were identified in the images with a cumulative length of ~5 m, corresponding to ~1% of the total borehole depth (Figure F11). Breakout widths range 28°–76° with a mean value of 50° (±13° standard deviation), whereas breakout azimuth ranges 70°–90°.

4. Lithostratigraphy

Site C0026 consists of four holes: C0026B–C0026E. Hole C0026B was drilled using the SD-RCB system to core from 80.00 to 290.00 mbsf (equivalent to the core depth below seafloor, Method A [CSF-A] depth scale). In contrast, Holes C0026C–C0026E were cored with the HPCS, with coring depths from the seafloor to 6.50 and 92.00 mbsf, respectively.

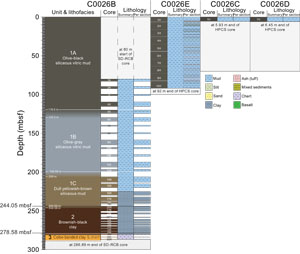

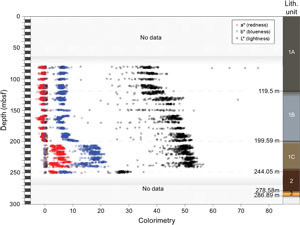

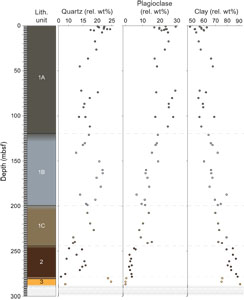

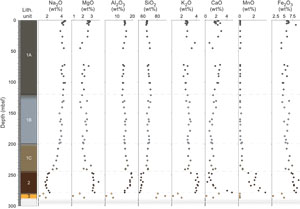

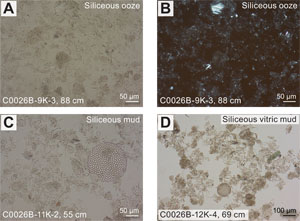

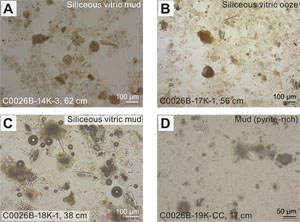

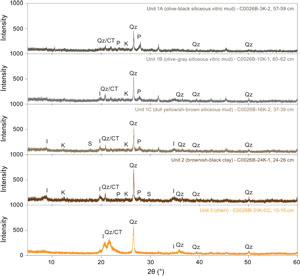

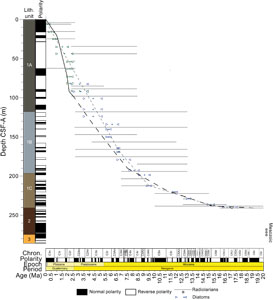

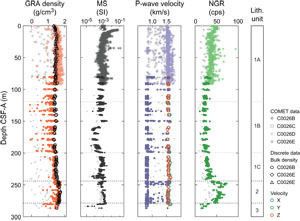

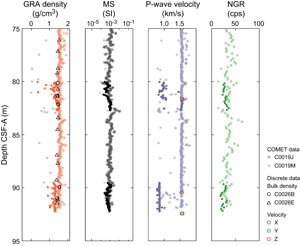

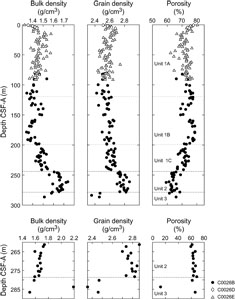

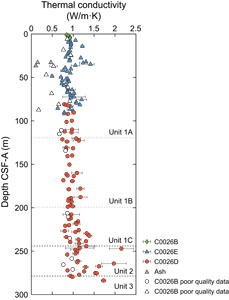

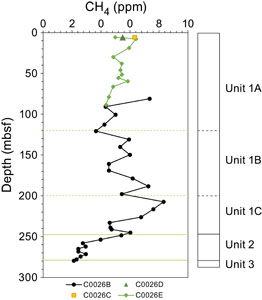

Three main lithostratigraphic units were identified at Site C0026 (Figure F12). Lithostratigraphic units are numbered 1–3 from the seafloor to the bottom of the cored interval (Table T7). They were distinguished based on grain size and sediment composition, supported by color variations (see Lithostratigraphy in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025a]). Representative intervals of each unit and unit boundaries are illustrated in Tri-Sensor Core Logger (TSCL) linescan images, modified linescan images, and X-ray computed tomography (XCT) images (Figures F14, F22, F24). Specific sedimentary features (e.g., soft-sediment deformation structures such as flame structures, load casts, and fining upward) are shown in Figure F17. Sediment compositions, derived from visual core descriptions and smear slides, are summarized in ternary diagrams (Figure F15; Table T8) and selected microscopic images (Figures F16, F20, F21, F23, F25). The grain size ranges presented for each subunit below record the range between the lowest (L) recorded and highest (H) recorded percent of each grain size fraction (displayed as L%-H%). It is noted that this smear slide analysis semiquantitative and further grain size distribution analysis is needed. Core colorimetry data from the TSCL display color variations across the units (Figure F13); however, TSCL colorimetry data is only available for Cores 405-C0026B-1K through 21K (80.00–250.42 mbsf). Variations in mineral assemblages and chemical compositions throughout the holes are documented using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Figures F18, F26; Table T9) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis (Figure F19; Table T10).

4.1. Unit 1

Because of the similar sediment composition and grain size of the background sedimentation throughout Unit 1, the division into Subunits 1A–1C is primarily based on color variations ascertained from visual core description and colorimetry (Figure F13), with Subunit 1C exhibiting a slightly higher proportion of siliceous biogenic material.

4.1.1. Subunit 1A

- Interval: 405-C0026B-1H-1, 0 cm, 405-C0026C-1H-1, 0 cm, 405-C0026D-1H-1, 0 cm, and 405-C0026E-1H-1, 0 cm, to 405-C0026B-5K-1, 0 cm

- Depth: 0–119.50 mbsf

- Age: 0.30–5.10 Ma (diatoms); 0.43–9.1Ma (radiolarians)

- Lithology: olive-black siliceous vitric mud

4.1.1.1. Visual core description lithology

Subunit 1A encompasses the entire cored interval of Holes C0026C–C0026E and the upper part of Hole C0026B. Based on visual core description, smear slide analysis, and XCT images, the recovered stratigraphic sequence correlates well across these cores (Figures F12, F14, F15, F16). As a result, we integrated the observations and data from the four cored intervals for Subunit 1A.

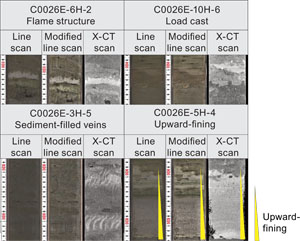

Subunit 1A is composed of olive-black siliceous vitric mud with common volcanic ash-rich layers, color banding, and extensive bioturbation. Color changes between the olive-black (7.5Y 3/1) background sedimentation and grayish olive (7.5Y 5/3), olive-gray (10Y 4/2), and dark greenish gray (7.5GY 4/1) define centimeter to decimeter compositional layers that contain variations in the abundance of volcanic and siliceous biogenic material (as demonstrated by the large scatter of the datapoints in the compositional ternary diagram displayed in Figure F15). Color changes from brownish to greenish in the color bands usually correlate with a higher abundance of volcanic glass, which is typically altered. In Cores 405-C0026E-2H through 10H, more than 120 ash-rich layers were identified, with thicknesses varying from 1 to 30 cm. Fining-upward grain size trends are commonly associated with thick, ash-rich layers but can occasionally be observed in siliciclastic beds. Soft-sediment deformation, such as load and flame structures, are typically observed at the top and bottom of the ash-rich layers (Figure F17).

The olive-black background sedimentation of Subunit 1A is moderately to heavily bioturbated, identifiable by subhorizontal and near-vertical lighter or darker mottles (Figure F14). Some burrows show black coloration, possibly due to the presence of pyrite or iron monosulfides. Silt-filled burrows are also visible in the XCT image and appear round to ellipsoidal in cross section, with simple, unlined, and unbranched structures suggesting Planolites. In particular, bioturbation with distinct crosscutting relationships is often concentrated above, through, and under ash-rich layers.

Ash-rich layers are (1) dark green–black banded (usually <5 cm thick), (2) light gray and almost 100% glass composition (2–30 cm thick), and (3) dark gray to brown, containing pumice and heavy minerals (2–10 cm thick), as well as combinations of the above. Most thick ash-rich layers exhibit sharp basal contacts with upward grading. Soft-sediment deformation structures, particularly flame structures, are often observed where the upper boundary of an ash-rich layer is well defined. Further investigations are needed to determine whether the occasionally irregular basal boundary of ash-rich layers is created by load structures or burrows. It is noted that these features could be more evident in these layers due to the color differentiation. The abundance of ash-rich layers appears to decrease in the lower part of Subunit 1A (Hole C0026B) compared to the upper part (Hole C0026E). However, it is unclear whether this difference reflects a genuine temporal variation or is due to the lower recovery rate of the SD-RCB coring system used in Hole C0026B compared to the higher recovery rate of the HPCS used in Hole C0026E. In addition to volcanic ash-rich layers, subrounded pumice clasts are disseminated throughout Subunit 1A with sizes from several millimeters to centimeters. These clasts are usually light gray-green but are occasionally brown and sometimes black if pyritized (Figure F14).

4.1.1.1.1. Smear slide petrography

The grain size of the Subunit 1A background sedimentation is predominately mud and ranges between sand (0%–40%), silt (15%–92%), and clay (5%–85%). The sand-sized fraction usually comprises large centric diatoms and pumice (Figure F16). The composition of the background sedimentation in Subunit 1A is siliceous to siliceous vitric mud composed of a range of siliciclastic (7%–74%), volcanic (3%–64%), and biogenic (5%–82%) material (Table T8; Figure F15). Other minor components (0%–20%) include dense or opaque minerals, framboidal pyrite, mica, glauconite, and calcite. Siliciclastic grains are mostly clay minerals (0%–62%) with small amounts of quartz (1%–35%) and mud aggregates (0%–35%), as well as minor contributions of feldspar (0%–2%). The biogenic portion is a mixture of diatoms (0%–50%), radiolarians (0%–35%), silicoflagellates (0%–20%), and sponge spicules (1%–38%). The volcanic portion of Subunit 1A is mostly clear glass (0%–55%), colored glass (0%–10%), and pumice (0%–15%). The dominant grain size of ash-rich layers is silt (65%–97%) with minor sand (1%–27%) and clay (0%–15%) size fractions.

4.1.1.1.2. Mineralogy and sediment geochemistry

A total of 22 bulk samples representative of Subunit 1A were collected for XRD analysis (Figure F18; Table T9). For each sample, the semiquantitative mineral mode by weight was estimated (see Lithostratigraphy in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025a]). Clay mineral content dominates the composition and ranges 48–69 wt%. Plagioclase ranges 17–29 wt%, and quartz ranges 14–25 wt%. The proportion of the three components is relatively consistent throughout Subunit 1A and supports observations of mostly clay minerals in the siliciclastic component from smear slides.

XRF and loss on ignition (LOI) analyses were performed in the same intervals, yielding ranges of 3.86–4.54 wt% Na2O, 1.70–2.82 wt% MgO, 13.53–16.04 wt% Al2O3, 64.78–70.71 wt% SiO2, 0.07–0.12 wt% P2O5, 2.27–3.80 wt% K2O, 1.15–2.80 wt% CaO, 0.43–0.69 wt% TiO2, 0.06–0.14 wt% MnO, 4.15–8.51 wt% Fe2O3, and 5.38–8.69 wt% LOI (Figure F19; Table T10). The high concentration of SiO2 is consistent with the relatively high proportions of volcanic glass and siliceous biogenic components observed in smear slides throughout Subunit 1A.

4.1.1.1.3. Summary and preliminary interpretation

The composition of Subunit 1A is dominated by siliceous biogenic material (diatoms and sponge spicules) with varying siliciclastic and volcanic components, indicating a hemipelagic depositional environment. Thick ash-rich layers have sharp contacts with concentrated bioturbation at the upper boundary and tend to display a fining-upward grain size distribution. Further work is required to distinguish the depositional mechanism for these event beds (e.g., primary volcanic ash fall or remobilization), but grain size trends and erosive basal contacts indicate higher energy compared to background sedimentation. The presence of sediment-filled veins and soft-sediment deformation structures (e.g., load and flame structures) further suggests possible links to past seismic activity.

4.1.1.2. Subunit 1B

- Interval: 405-C0026B-5K-1, 0 cm, to 13K-CC, 18.5 cm

- Depth: 119.50–199.59 mbsf

- Age: 3.5–9.1 Ma (diatoms); 2.3–16.6 Ma (radiolarians)

- Lithology: olive-gray siliceous vitric mud

4.1.1.2.1. Visual core description lithology

Subunit 1B is composed of olive-gray siliceous vitric mud characterized by a mixture of siliceous biogenic and vitric components (Figures F12, F14, F15, F20). A notable increase in the colorimetry lightness values in Core 405-C0026B-5K defines a color transition that is interpreted to represent a gradational lithologic contact between Subunits 1A and 1B (Figure F13). Features such as bioturbation, color banding, and volcanic ash-rich layers are commonly identified throughout Subunit 1B. Layering is defined by color changes between olive-gray (7.5Y 4/1), grayish olive (7.5Y 5/3), olive-gray (10Y 4/2), and dark greenish gray (7.5GY 4/1), which result from variations in the relative abundance of volcanic and biogenic material. Although soft-sediment deformation structures are less common than in Subunit 1A, graded (usually ash-rich) beds with flame structures at the top and erosive basal surfaces (e.g., Section 8K-2) (Figure F17) remain present, indicating deposition from higher energy sedimentary events was interspersed with the background sedimentation (as in Subunit 1A).

The olive-gray background sediments of Subunit 1B are moderately to heavily bioturbated and identifiable by subhorizontal and subvertical lighter or darker mottles (Figure F14). Some burrows show black coloration due to the presence of pyrite or iron monosulfides. Silt-filled burrows are also visible in the XCT image and appear round to ellipsoidal in cross section, with simple, unlined, and unbranched structures suggesting Planolites. In particular, bioturbation with distinct crosscutting relationships is often concentrated above, through, and below ash-rich layers.

A total of 13 ash beds are identified in Subunit 1B, most of which are thinner (1–3 cm) and darker than the lighter and thick ash-rich layers identified in Subunit 1A.

4.1.1.2.2. Smear slide petrography

The Subunit 1B background sedimentation grain size is predominantly mud and ranges between sand (2%–35%), silt (20%–75%), and clay (15%–60%), which is overall less silty compared to Subunit 1A (Figure F15; Table T8). The sand-sized fraction usually comprises large centric diatoms or pumice (Figure F20). The average sediment composition is siliciclastic (18%–80%), volcanic (2%–70%), and biogenic (0%–70%) material, reflecting a significant variability. Siliciclastic grains are mostly clay minerals (5%–49%) and mud aggregates (0%–35%) with small amounts of quartz (0%–15%) and feldspar (0%–7%). The volcanic portion of Subunit 1B is mostly clear glass (2%–50%), colored glass (0%–20%), and pumice (0%–30%). The biogenic portion of Subunit 1B is a mixture of diatoms (1%–42%), radiolarians (0%–15%), and sponge spicules (0%–35%). Other minor components (0%–21%) consist of dense or opaque minerals and framboidal pyrite.

The dominant grain size of ash-rich layers is silt (40%–80%), with variable amounts of sand (15%–40%) and clay-sized (5%–25%) fragments. This result is less silty and slightly clayey compared to the ash-rich layers in Subunit 1A (Table T8; Figure F15). The ash layers are volcanic and contain 65%–90% volcanic components, alongside siliciclastic (8%–15%) and biogenic (0%–10%) components. The volcanic component is made up of clear glass (20%–75%), colored glass (0%–5%), and pumice clasts (10%–60%).

4.1.1.2.3. Mineralogy and sediment geochemistry

A total of 13 bulk samples representative of Subunit 1B were collected for XRD analysis (Table T9). Clay mineral content dominates the composition and ranges 60–80 wt% (Figure F18). Plagioclase ranges 8–15 wt%, and quartz ranges 12–19 wt%. Notably, the proportions of the two components gradually change throughout Subunit 1B, with plagioclase content decreasing downcore as clay content increases.

XRF analyses and LOI measurements were performed for the same intervals as XRD measurements to obtain major and minor element concentrations. The results indicate ranges of 3.72–4.31 wt% Na2O, 1.70–2.48 wt% MgO, 13.38–16.02 wt% Al2O3, 65.89–71.17 wt% SiO2, 0.07–0.10 wt% P2O5, 2.64–3.23 wt% K2O, 1.15–2.08 wt% CaO, 0.44–0.64 wt% TiO2, 0.07–0.34 wt% MnO, 4.45–6.52 wt% Fe2O3, and 5.83–7.28 wt% LOI (Figure F19; Table T10). The concentration of SiO2 is consistent with the relatively high proportions of volcanic glass and siliceous biogenic components in this unit.

4.1.1.2.4. Summary and preliminary interpretations

The olive-gray siliceous vitric mud of Subunit 1B is compositionally differentiated from Subunit 1A by reduced volcanic clasts. Approximately 13 ash beds are identified in Subunit 1B, most of which are thinner and darker compared to Subunit 1A. Bioturbation remains prominent throughout Subunit 1B, but soft-sediment deformation structures are less abundant. The age of Subunit 1B (3.54–9.10 Ma) (see Biostratigraphy) and the compositional shift between Subunits 1A and 1B suggest a similar hemipelagic depositional environment dominated by biogenic source but with decreased volcanic input, potentially resulting from either (1) increased distance from volcanic sources or (2) reduced volcanic activity.

4.1.1.3. Subunit 1C

- Interval: 405-C0026B-13K-CC, 18.5 cm, to 20K-1, 5 cm

- Depth: 199.585–244.050 mbsf

- Age: 9.30–17.50 Ma (diatoms); 2.70–20.00 Ma (radiolarians)

- Lithology: dull yellowish brown siliceous mud

4.1.1.3.1. Visual core description lithology

Subunit 1C is a siliceous mud similar in composition to Subunit 1B but differentiated by a notable change in color from the typical olive-gray siliceous mud lithology of Subunit 1B to a dull yellowish brown siliceous mud (10YR 5/4) (Figures F12, F13). The precise depth and nature of the transition from Subunit 1B to Subunit 1C are uncertain because of the lack of continuous core recovery between Cores 405-C0026B-13K (199.59 mbsf) and 14K (206.00 mbsf). However, the provisional boundary is interpreted to lie within the unrecovered 6.6 m interval between the base of Section 13K-CC and the top of Section 14K-1. The background sediment composition remains generally consistent across the color change and throughout Subunit 1C, but there is a notable downcore decrease in the proportion of volcanic material and the number of ash-rich layers compared to Subunit 1B. Based on these changes, the dull yellowish brown mud lithology was defined as Subunit 1C.

A total of 13 ash-rich layers were described throughout Subunit 1C and are identifiable by their dark color and silt-sized glass shards. Ash-rich layers in Subunit 1C contain more brown glass (17%) compared to Subunit 1B. Bioturbation often occurs throughout the ash-rich layers, with many burrows appearing black because of pyritization.

4.1.1.3.2. Smear slide petrography

The Subunit 1C background sediment grain size plots predominantly as mud and ranges between sand (1%-50%), silt (20%–57%), and clay (10%–74%). However, this unit is characterized by a downward increasing proportion of clay-sized grains with depth, accompanied by gradually increasing biogenic material through the unit that is absent in the previous two subunits (Figure F15; Table T8). Overall, Subunit 1C has a similar composition to Subunit 1B, featuring a mix of ranges of siliciclastic (3%–74%), volcanic (0%–67%), and siliceous biogenic (10%–85%) material (Figure F21). The proportion of biogenic components increases downcore in Subunit 1C (e.g., Core 405-C0026B-18K). Notably, a spike in radiolarians is observed in smear slides from Cores 16K and 17K. The volcanic component in the representative background mud (excluding ash-rich layers) decreases downcore to <5%, whereas clay minerals and mud aggregates/clasts dominate (>80%) near the base. This shift is accompanied by an increase in dense minerals, and pyrite.

4.1.1.3.3. Mineralogy and sediment geochemistry

Six bulk samples representative of Subunit 1C were collected for XRD analysis (Table T9). The trends in mineralogy noted in Subunit 1B continue to the bottom of Subunit 1C, with an increase in clay average for Subunit 1C (~74 wt%) and a decrease in average plagioclase (~11 wt%) (Figure F18). These results are in agreement with observations of increased clay from smear slide analysis.

XRF analyses conducted at the same intervals as XRD measurements for Subunit 1C reveal a decrease in SiO2 consistent with the increasing clay content observed in XRD data. The results show ranges of 2.78–3.53 wt% Na2O, 1.98–2.91 wt% MgO, 15.32–17.07 wt% Al2O3, 65.16–67.35 wt% SiO2, 0.08–0.19 wt% P2O5, 2.48–3.22 wt% K2O, 1.20–1.99 wt% CaO, 0.55–0.66 wt% TiO2, 0.10–0.42 wt% MnO, 5.42–7.41 wt% Fe2O3, and 6.44–8.33 wt% LOI (Figure F19; Table T10). Overall, the geochemical composition of the top of Subunit 1C shows a continuation of the characteristics from Subunit 1B. However, samples at the base of Subunit 1C reflect relative clay enrichment and a reduction in the biogenic component, indicated by the decrease in SiO2 and increase in Fe2O3.

4.1.1.3.4. Summary and preliminary interpretations

Subunit 1C is a dull yellowish brown siliceous mud(stone) that is marked by a further decrease in the volcanic component from Subunit 1B. Biogenic material in Subunit 1C shows a notable increase in radiolarians to ~232 mbsf, where biogenic material decreases to almost 0% at the base of the unit. The lower abundance of ash-rich/vitric components, decreased biogenic material, and lack of significant soft-sediment deformation structures indicate a low-energy depositional environment. This places Site C0026 at a location farther from the active margin than Subunits 1A and 1B (Moore et al., 2015).

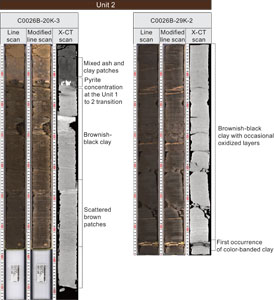

4.1.2. Unit 2

- Interval: 405-C0026B-20K-1, 5 cm, to 29K-2, 65 cm

- Depth: 244.050–278.575 mbsf

- Age: TBD (the occurrence of radiolarians that lived only in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods is noted)

- Lithology: brownish black clay

4.1.2.1. Visual core description lithology

Unit 2 is a dark brown to brownish black clay. The transition from Subunit 1C to Unit 2 is transitional and is defined by an intercalation of the yellowish brown and brownish black clay layers in Sections 405-C0026B-20K-1, 5 cm, through 20K-3, 13 cm (i.e., 2.53 m thick interval). However, the sharpest color change occurs in Section 20K-3, 13 cm (246.58 mbsf), where a ~1 cm thick concentration of pyrite marks the transition (Figure F22). Below this depth, the dull yellowish brown lithology is no longer present. The clay in Unit 2 displays a consistent brownish black color (7.5YR 2/2), with slight variations ranging from dark brown (7.5YR 2/3) to black (7.5YR 2/1). The clay is relatively structureless and occasionally contains rare thin layers and interspersed orange-brown (10YR 5/2) patches, typically less than ~2 cm in diameter. Bioturbation, mottling, and biogenic material are rare in Unit 2. No identifiable ash-rich layers were found in Unit 2. Fossilized fish teeth were found in Section 26K-1 at 3.5 and 5.6 cm.

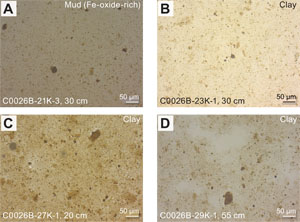

4.1.2.2. Smear slide petrography

Smear slide analysis indicates that the grain size is much finer than in Unit 1 and plots as clay (Table T8). The grain size ranges between clay (68%–83%), silt (15%–30%), and sand (0%–4%) are in the color change zone at the top of Unit 2 (Cores 405-C0026B-20K and 21K), and most of the visible grains are lithic fragments and secondary pyrite growth (Figures F22, F23A). However, coarse-grained particles are nearly absent toward the bottom of the unit, where the sediment consists mostly of clay (60%–100%) with some silt (0%–38%) and sand (0%–10%). Unit 2 is predominantly composed of siliciclastic grains (67%–100%), with minimal volcanic (0%–11%) and biogenic (0%–10%) components (Figure F15). Other minor components (0%–32%) include rare occurrences of dense and opaque minerals, framboidal pyrite, and Fe oxides. Siliciclastic grains are mostly clay minerals (59%–100%), with some quartz (0%–2%) and mud aggregates/clasts (0%–7%).

4.1.2.3. Mineralogy and sediment geochemistry

A total of 10 bulk samples representative of Unit 2 were collected for XRD analyses (Table T9). Unit 2 features a dominance of clay minerals (79%–89%) and a substantial reduction in quartz (7%–16%) and plagioclase (2%–6%) compared to Unit 1 (Figure F18). XRD data support the observations from smear slides that Unit 2 consists predominantly of clay.

The same samples were analyzed for major and minor element contents using XRF (Table T10). The results range 1.75–2.36 wt% Na2O, 3.05–3.77 wt% MgO, 15.04–19.73 wt% Al2O3, 55.71–60.92 wt% SiO2, 0.16–2.35 wt% P2O5, 3.26–4.30 wt% K2O, 0.86–4.29 wt% CaO, 0.68–1.08 wt% TiO2, 1.24–3.67 wt% MnO, 7.19–9.34 wt% Fe2O3, and 7.40–8.70 wt% LOI (Figure F19). Increased MgO, Al2O3, and K2O content can be related to the predominance of clay in Unit 2. The enrichment of Fe/Mn oxides and pyrite is reflected by the MnO and Fe2O3 values. Lower SiO2 is consistent with the near absence of siliceous biogenic material and reduced abundance of vitric fragments and ash-rich layers.

4.1.2.4. Summary and preliminary interpretations

Unit 2 reflects a change to a clay-dominated lithology, contrasting significantly with Unit 1. Unit 2 contains >90% siliciclastic components (mostly clay minerals), and compositions are rich in Fe oxides and pyrite. The absence of biogenic components (radiolarians and diatoms) and ash-rich layers in this unit also marks a clear shift from previous units. Occasional thin layers and orange-brown patches are likely due to localized chemical alterations or subtle depositional variations. The enrichment of Fe oxides and occasionally observed pyrite indicates both oxic and localized anoxic conditions during deposition. Because of the dominance of very fine grained clay, coupled with the near absence of biogenic material, Unit 2 is interpreted to be pelagic clay that accumulated on the Pacific plate in an area far from continental margins.

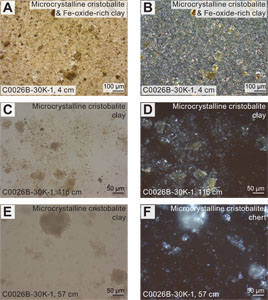

4.1.3. Unit 3

- Interval: 405-C0026B-29K-2, 65 cm, to 32K-CC, 20 cm

- Depth: 278.575–286.885 mbsf

- Age: Mesozoic (identified from the occurrence of radiolarians that lived only in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods)

- Lithology: color-banded clays and chert

4.1.3.1. Visual core description lithology

Unit 3 consists of color-banded clays intercalated with intervals of chert, recovered as broken fragments. The top of Unit 3 is characterized by a gradual transition from the dark-brown clay of Unit 2 to a color-banded clay (Figures F12, F24). This transition is marked by the first appearance of a 1 cm thick band of dull yellowish brown clay, including a clast of greenish clay in Section 405-C0026B-29K-2, 65 cm (Figure F22). Colors in the banded clay interval include black (7.5YR 2/1), brownish black (7.5YR 2/2), brown (7.5YR 4/6), dull orange (7.5YR 3/3), and light yellow (5Y 1/3). The color bands become progressively thicker (millimeter to centimeter thick), brighter, and more lithified downcore, with millimeter-scale brown and dull orange laminations to the first chert in Section 30K-1, 105 cm. The chert fragments are lithified, and fragmentation is interpreted to result from coring. The appearance of the chert is variable. In Core 31K, the chert is light yellow and intercalated with a light yellow porcellanitic clay. In Section 30K-CC, the chert is color-banded with brownish black, brown, and light yellow bands crosscut by a silica vein. Although intervals of chert appear more often toward the base of Unit 3, color-banded clays persist to the bottom of Hole C0026B. Notably, following the recovery of chert from Sections 30K-CC through 32K-1, the deepest recovered lithology in Section 32K-CC reverts to banded clay, suggesting alternations between chert and clays in Unit 3.

4.1.3.2. Smear slide petrography

Observations from smear slides indicate that Unit 3 is largely composed of clay and SiO2 microlites (Figures F15, F25). Smear slide data suggest the proportion of clay minerals in the brownish black clay is higher than that in the light yellow porcellanitic clay. Conversely, the light yellow porcellanitic clay exhibits a slightly higher proportion of SiO2 compared to the dark brown clay. The Unit 3 background sedimentation grain size is mud and ranges between sand (0%–10%), silt (8%–70%), and clay (23%–92%). The average sediment composition is composed of siliciclastic (82%–98%) and volcanic (0%–3%) material (Table T8). Other minor components (0%–17%) consist of dense minerals and pyrite. Siliciclastic grains are mostly quartz (5%–86%) with clay minerals (0%–75%), chert (0%–12%), and mud aggregates (3%–20%).

4.1.3.3. Mineralogy and sediment geochemistry

Three samples, one from the color-banded clay (Sample 405-C0026B-30K-1, 62–64 cm), one from the yellow porcellanite (Sample 31K-CC, 13–15 cm), and one from the dark brown clay (Sample 32K-1, 10.5–12.5 cm), were sampled for XRD analysis (Figure F26; Table T9). Results of semiquantitative mineral abundance analyses are similar between the color-banded clays and porcellanite samples with approximately 75% clay minerals, 20%–25% quartz, and <5% plagioclase (Figure F18).

The same samples were analyzed for element composition using XRF (Table T10; Figure F19). The results are broadly similar between the color-banded clays and dark brown clay, ranging 1.48–1.82 wt% Na2O, 1.64–2.14 wt% MgO, 6.45–7.50 wt% Al2O3, 78.85–80.95 wt% SiO2, 0.84–1.39 wt% P2O5, 1.50–2.01 wt% K2O, 1.68–2.47 wt% CaO, 0.29–0.41 wt% TiO2, 0.02–0.04 wt% MnO, 4.28–4.97 wt% Fe2O3, and 5.88–6.09 wt% LOI. Results for the light yellow porcellanitic clay samples are quite different at 0.96 wt% Na2O, 0.89 wt% MgO, 3.12 wt% Al2O3, 91.36 wt% SiO2, 0.39 wt% P2O5, 0.87 wt% K2O, 0.73 wt% CaO, 0.16 wt% TiO2, 0.01 wt% MnO, 1.68 wt% Fe2O3, and 4.01 wt% LOI. This difference likely reflects the increased concentration of SiO2 associated with chert formation.

4.1.3.4. Summary and preliminary interpretations

Unit 3 presents a transition from the dark brown clay into color-banded clays and lithified chert. Unit 3 lacks biogenic and volcanic components. The presence of millimeter-scale laminae in the color-banded clays suggests minimal transport and/or disturbance of Unit 3. The color banding in the Unit 3 clays reflects different levels of SiO2 present in the laminae, suggesting that the degree of silicification in these clays varies over centimeter length scales. The increasing content of SiO2 microlite and transitional occurrence of color-banded clay, porcellanitic clay, and chert suggest that silicification/lithification processes that transform the clay into chert are ongoing.

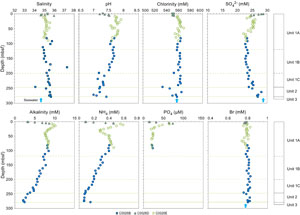

4.2. Summary and preliminary assessment

Four boreholes were drilled at Site C0026 (Holes C0026B–C0026E), with overall very good recovery (>50%). Together, the cores recovered from these holes provide a relatively complete record of the entire sequence of subseafloor sediments that overlie the incoming Pacific plate at the Japan Trench from 0 to 290 mbsf. Three primary lithostratigraphic units were identified as part of the stratigraphic sequence, all of which are consistent with deposition in an open marine setting. Biostratigraphic correlations indicate the sediments range from Cretaceous to present age (see Biostratigraphy). The Cretaceous color-banded clay and chert (Unit 3) and Cretaceous to Miocene brownish black pelagic clay (Unit 2) are composed predominantly of silica and clay minerals, respectively, with a notable absence of biogenic and volcaniclastic material, suggesting they were deposited in a deepwater hemipelagic setting. The transition from the Miocene to present-day mudstone in Unit 1 is marked by an increase in the biogenic and volcaniclastic components and represents a change in depositional environment to relatively undisturbed background sedimentation in a hemipelagic environment, with an increase in sediment provided from volcanic sources. All units lack calcareous nannofossils, suggesting they were deposited below the carbonate compensation depth. This stratigraphic progression is consistent with changes in depositional environments controlled by the motion of the Pacific plate as Site C0026 was translated toward the continental margin over time (e.g., Moore et al., 2015).

The sediments recovered at Site C0026 are similar to those recovered at DSDP Site 436, the nearest drilling site that can be used as a comparison, which is located >250 km north of Site C0026 off northern Honshu (Shipboard Scientific Party, 1980). Site 436 consists of three lithostratigraphic units: Subunits 1A and 1B (vitric diatomaceous silty clay and claystone), Unit 2 (radiolarian diatomaceous claystone), and Subunits 3A and 3B (pelagic clay with chert and porcellanite). Based on the lithologies and ages of these units, the Site 436 units correspond with Site C0026 Subunits 1A and 1B, Subunit 1C, and Units 2 and 3, respectively. However, the unit thicknesses are different. For example, the interval to the base of the upper Miocene, which corresponds approximately to Subunits 1A and 1B at Site 436 is 312 m thick at Site 436 (according to the depth of the base of Site 436 Subunit 1B), whereas the equivalent interval in Subunits 1A and 1B at Site C0026 is ~200 m thick (according to the depth of the base of Site C0026 Subunit 1B). Dacite pebbles were recovered in the Pliocene to late Miocene cores at Site 436 but were absent at Site C0026.

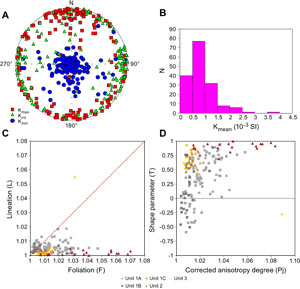

5. Structural geology

Cores recovered from Site C0026 sampled the sedimentary inputs on the incoming Pacific plate from 0 to ~290 mbsf, outboard of the Japan Trench (note that all depths in this section are provided on the mbsf depth scale, which is equivalent to the CSF-A scale). Generally, the deformation of these incoming sedimentary input units was minimal, consisting mostly of fractures, some minor faults, sediment-filled veins, and scaly fabric in pelagic clays. For all structures, orientations were obtained on the working-half sections of cores for Holes C0026B–C0026E using visual core description and complemented by measurements using XCT. In selected coherent sections, discrete samples were analyzed paleomagnetically (see Paleomagnetism) to correct the orientation of the core to the geographic reference frame, allowing strikes of planar features to be estimated for true in situ alignment.

5.1. Hole C0026C

Hole C0026C cored the sedimentary rocks on the incoming Pacific plate from 0 to 5.90 mbsf. The sedimentary rocks in this hole consist of olive-black siliceous vitric mud (Lithostratigraphic Subunit 1A). Primary structures consisted of planar bedding. Secondary structures related to deformation were not identified in Section 1H.

5.1.1. Bedding and laminae

The orientation of one subhorizontal bed was measured (Figure F27).

5.1.2. Deformation structures

No deformation structures were identified.

5.2. Hole C0026D

Hole C0026D penetrated the sedimentary rocks on the incoming Pacific plate. Hole recovery was from 0 to 6.45 mbsf. The sedimentary rocks in this hole consist of olive-black siliceous vitric mud (Lithostratigraphic Subunit 1A). Primary structures consisted of planar bedding. Secondary structures related to deformation were not identified in Section 1H.

5.2.1. Bedding and laminae

The orientations of eight horizontal to subhorizontal bedding planes were measured (Figure F27).

5.2.2. Deformation structures

No deformation structures were identified.

5.3. Hole C0026E

Hole C0026E penetrated the sedimentary rocks on the incoming Pacific plate. Hole recovery was from 0 to 92.39 mbsf. The sedimentary rocks at this site consist of olive-black siliceous vitric mud (Lithostratigraphic Subunit 1A). Two minor faults were identified in Sections 9H-8 and 10H-6, both with undetermined senses of slip. A total of 10 sediment-filled veins were identified in Cores 2H–4H. Additionally, sand injections were identified in Section 2H-5.

5.3.1. Bedding and laminae

The strike and dip of 102 beds were measured. The average orientation was subhorizontal (Figure F27).

5.3.2. Deformation structures

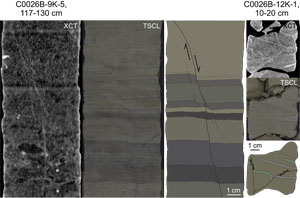

5.3.2.1. Fractures and minor faults

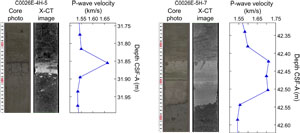

Two minor faults were visible in the core at 81.93 mbsf (Section 405-C0026E-9H-8) and 89.53 mbsf (Section 10H-6). These faults are only weakly expressed on split core faces. However, they are easily discernible on XCT images, appearing as bright, planar structures that truncate planar bedding. The higher XCT number associated with fault planes is attributed to a higher density material along the fault plane compared to the surrounding material, potentially due to compaction of the materials at the fault plane or to mineralization. The identified minor faults have an undetermined sense of motion and have true dips of 8° and 53°, respectively.

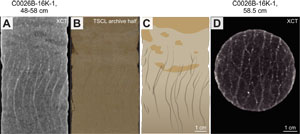

5.3.2.2. Sediment-filled veins

A total of 10 intervals of sediment-filled veins were identified in Sections 405-C0026E-2H-6, 3H-2, 3H-5, 4H-3, 4H-5, and 4H-7. These sediment-filled veins appear as parallel to subparallel, vertical to subvertical, curvilinear to sigmoidal millimeter thick bands. Traces of the veins in axial sections through the core anastomose, indicating the veins are interconnected. Their vertical length varies between 2 and 21 cm with average intervein spacings of 2–10 mm. The veins have a higher XCT number than the surrounding rocks, indicating denser material.

5.4. Hole C0026B

Core recovery in Hole C0026B was from 80.0 to 286.69 mbsf. The sedimentary rocks in this hole consist of siliceous muds (Lithostratigraphic Subunits 1A–1C), brownish-black clay (Unit 2), and color-banded clay and chert (Unit 3). The sedimentary rocks are well stratified and largely undeformed. Features observed and measured in cores (using visual core description and/or XCT) include bedding planes, minor faults, fractures, sediment-filled veins, scaly fabric, and laminae. The distribution of structures is illustrated in Figure F27.

5.4.1. Bedding and laminae

In total, 84 bedding and laminae orientations were measured. The average dip of bedding and laminae in Hole C0026B is 7° (total range = 0°–32°) (Figure F27). One normally oriented flame structure was noted inside a 7 cm long biscuit at 110.66 mbsf (Section 405-C0026B-4K-2).

5.4.2. Deformation structures

5.4.2.1. Fractures and minor faults

The strike and dip of 20 fractures and 11 minor faults were measured in Hole C0026B. We labeled cracks as "fractures" when neither opening mode nor shear sense of motion (e.g., offset features, truncated bedding, striations, and presence of gouge) could be determined. Minor faults were identified as planar structures with measurable millimeter- to centimeter-scale offsets of piercing points defined by truncation and displacement of bedding, other fractures, or bioturbation or by the presence of striations. Of the 11 minor faults, 2 had reverse offset, 8 had normal offset, and 1 did not have identifiable sense-of-slip indicators. The average dip angles for fractures and faults were ~45° and ~60°, respectively, and there was no difference in the dip of normal and reverse structures (Figure F27). Representative minor faults are shown in Figure F28. The fracture dip angle increases slightly with increasing depth in the core.

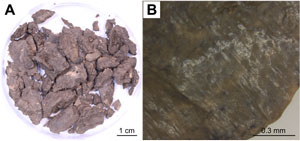

5.4.2.2. Scaly fabric

Between 245.74 and 246.74 mbsf (Sections 405-C0026B-20K-2 and 20K-3), scaly fabric was observed in whole-round samples in dull yellowish brown siliceous mud (Subunit 1C) and brownish black clay (Unit 2) in the transitional interval where these two lithologies are interbedded. The scaly fabric is composed of wedge- to discoidal-shaped clay phacoids. These phacoids have subangular to subrounded edges and a bimodal size distribution such that larger phacoids are generally 2–4 cm long and 1–1.5 cm wide and smaller phacoids are generally 0.4–0.6 cm long and 0.3–0.5 cm wide. Phacoid surfaces are moderately polished and frequently have parallel striations (Figure F29). Below Section 20K-3, it was difficult to assess whether the scaly fabric was present because of clay smearing when the core was split; therefore, we could not determine whether scaly fabric continues downsection.

5.4.2.3. Sediment-filled veins

Sediment-filled veins were observed in bioturbated, dull yellowish brown mud (Lithostratigraphic Subunit 1C). Five areas of sediment-filled veins were documented at 225.09–229.21 mbsf (in Sections 405-C0026B-16K-1, 16K-3, and 16K-4). The veins identified in Hole C0026B are geometrically similar to veins observed in Hole C0026E and are characterized by several parallel to subparallel, interconnected, vertical to subvertical, curviplanar to sigmoidal millimeter-scale bands (Figure F30). The vertical length of the vein arrays ranges 1–16 cm with an average intervein spacing of 1–10 mm. These veins are easily identifiable on XCT images as bright, white features related to a higher XCT number representative of the higher density of the vein-filling sediment.

5.4.2.4. Orientations of deformation structures

Core rotation during drilling operations produces incorrect structural orientations in recovered core. To correct for this rotation within a single coherent interval, the declination of the paleomagnetic vector was used to rotate the orientations of structural features to true in situ alignments (see Structural geology in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025a]). A total of 32 primary and secondary structural orientations in Hole C0026B were corrected to paleomagnetic north, and in situ strikes were calculated with respect to true north (Figure F31). The corrected orientations of the bedding are subhorizontal. Only four of the aforementioned faults were measured in sections where paleomagnetic discrete data were collected. Therefore, in situ orientations for the other deformational structures could not be determined.

5.5. Drilling-induced deformation

Drilling-related disturbances were commonly observed in Site C0026 cores. The disturbances to core structures and lithologies caused by piston coring primarily manifested as laminar arching of primary layering and flow-in. Flow-in was notably pronounced below a particular ash layer (56.54–56.80 mbsf) (Figure F32). In the SD-RCB coring section of Hole C0026B, biscuiting and drilling breccias were observed at intervals of several tens of centimeters. These drilling disturbances were identified on working-half and archive-half core surfaces and from CT images, and they were described as a distinct category separately from primary deformation structures.

5.6. Interpretation

The three stratigraphic units that form the sedimentary part of the incoming Pacific plate stratigraphy are identified in the cored units from Holes C0026B–C0026E. Minor faults, fractures, and scaly clay most likely form because of compaction during burial, as evidenced by predominantly normal-sense faulting and subhorizontal fabric in clays. Sediment-filled veins are commonly found in sediments in subduction zones such as the Nankai Trough (Tobin et al., 2020), Miura-Boso accretionary prism (Hanamura and Ogawa, 1993; Maltman et al., 1993), and Anafi Island Basin (Druitt et al., 2024). Based on field and experimental studies, such veins are thought to form because of shaking and dewatering during earthquakes (Hanamura and Ogawa, 1993; Brothers et al., 1996). We infer that the formation of sediment-filled veins on the incoming Pacific plate outboard of the Japan Trench is analogous to sediment-filled veins identified along other seismically active subduction margins.

6. Biostratigraphy

All core catcher samples drilled with the SD-RCB system in Hole C0026B and the HPCS in Holes C0026C–C0026E were examined for radiolarian biostratigraphy. For diatom biostratigraphy, core catcher samples from all cores in Holes C0026B and C0026E were examined.

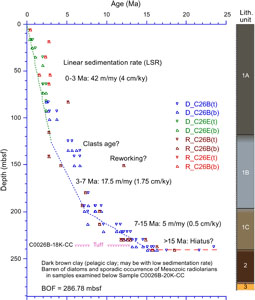

Diatoms and radiolarians were continuously observed in the Pleistocene to lower Miocene section down to Sample 405-C0026B-19K-CC (~241.2 mbsf), but samples between Samples 20K-CC (~247.5 mbsf) and 30K-CC (~280.8 mbsf) are barren of diatoms and only contain sporadic occurrences of Mesozoic radiolarians. Below Sample 31K-CC (~283.90 mbsf) to the bottom of the hole at 286.75 mbsf, no microfossils were detected at Site C0026. The results of diatom (Tables T11, T12) and radiolarian (Tables T13, T14, T15, T16) biostratigraphy from the Pleistocene through Miocene at Site C0026 is almost consistent, although some offset data may be caused by a differentiation between matrix/clast age and/or reworking of age diagnostic species (Figure F33).

DSDP Site 436 (39°55.96′N, 145°33.47′E; 5240 m water depth), drilled at the Japan Trench outer rise, is located ~240 km north-northeast from Site C0026. The site penetrated to 397.50 mbsf and collected cores that were well dated by diatom and radiolarian biostratigraphy. Barron et al. (1980) documented that Pleistocene through Miocene sediments were recovered from 0 to 360 mbsf and Miocene to Paleogene sediments from 360 to 378 mbsf above early radiolarian-rich Cretaceous chert (378–397 mbsf) containing pore microfossils. Compared to the diatom (Harper, 1980) and radiolarian biostratigraphy (Sakai, 1980) at Site 436, our observations at Site C0026 suggest that the thickness of Pleistocene–Miocene biosiliceous sediments at Site 436 is 1.5 times thicker; however, there are no significant differences detected on the timing of accumulation of siliceous microfossils between Sites 426 and C0026.

6.1. Diatoms

All core catcher samples obtained from Site C0026 in November 2024 were sent once per week to the Marine Core Research Institute (MaCRI) at Kochi University (Japan). For samples from Holes C0026B and C0026E, smear slides were made in the onshore laboratory and examined for diatom biostratigraphy (Table T11) (see Biostratigraphy in the Expedition 405 methods chapter [Kirkpatrick et al., 2025a]). Samples from Holes C0026C and C0026D will be examined during postexpedition research to reconfirm the age determination for the Pleistocene interval.

Common to abundant diatoms are found in all samples from Hole C0026E and in Samples 405-C0026B-1K-CC to 16K-CC, which corresponds to a Pleistocene through middle Miocene section. Diatoms were rare in Samples 17K-CC and 19K-CC and correspond to the deeper lower Miocene. Samples 18K-CC and 20K-CC through 32K-CC, toward the base of Hole C0026B, are barren of diatoms (Table T11). Chaetoceros resting spores, considered a seasonal upwelling indicator, are common to abundant in samples from the Pleistocene section obtained from Hole C0026B. Middle Miocene diatoms are detected as reworked diatoms in the Pliocene to Pleistocene section; however, there is no signal of Paleogene–Cretaceous diatoms in any sample examined at Site C0026 (Figure F33).

Diatom biohorizons/datums tentatively recognized during the expedition are summarized in Table T12.

6.1.1. Hole C0026E

The occurrence of Pleistocene boreal diatoms such as Thalassiosira gravida, Neodenticula seminae, and Shionodiscus oestrupii (without Neodenticula koizumii) in Sample 405-C0026E-1H-CC, 17.0–22.0 cm (6.12–6.17 mbsf), indicates this sample can be placed in North Pacific diatom (NPD) Zones NPD12–NPD10 (0–2.0 Ma). The occurrence of Fragilariopsis doliolus in this sample supports this interpretation. Reworked Miocene diatoms such as Crucidenticula punctata, Denticulopsis dimorpha var. areolata, and Fragilariopsis jouseae are observed, along with common and various neritic and freshwater diatoms such as Aulacoseira spp., Actinocyclus spp., Cocconeis spp., Cyclotella spp., Cymbella spp., Delphineis spp., Diploneis spp., Gramatophora spp., and Paralia sulcata.