Arculus, R.J., Ishizuka, O., Bogus, K., and the Expedition 351 Scientists, 2015

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 351

publications.iodp.org

doi:10.14379/iodp.proc.351.102.2015

Expedition 351 methods1

R.J. Arculus, O. Ishizuka, K. Bogus, M.H. Aljahdali, A.N. Bandini-Maeder, A.P. Barth, P.A. Brandl, R. do Monte Guerra, L. Drab, M.C. Gurnis, M. Hamada, R.L. Hickey-Vargas, F. Jiang, K. Kanayama, S. Kender, Y. Kusano, H. Li, L.C. Loudin, M. Maffione, K.M. Marsaglia, A. McCarthy, S. Meffre, A. Morris, M. Neuhaus, I.P. Savov, C.A. Sena Da Silva, F.J. Tepley III, C. van der Land, G.M. Yogodzinski, and Z. Zhang2

Keywords: International Ocean Discovery Program, IODP, JOIDES Resolution, Expedition 351, Site U1438, Izu Bonin Mariana, arc origins, subduction initiation, Earth connections, Amami Sankaku Basin, Kyushu-Palau Ridge, basalt, volcanic ash, breccia-conglomerate, biostratigraphy, magnetostratigraphy, oceanic crust, arc basement, Neogene, Paleogene, foraminifers, radiolarians, volcaniclastic, back arc, tuffaceous mud, hemipelagic, East Asian Monsoon, subduction factory

MS 351-102: Published 25 August 2015

Introduction

This chapter documents the procedures and methods used in the shipboard laboratories during International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 351. This introductory section provides a rationale for the site location and an overview of IODP depth conventions, curatorial procedures, and general core handling/analyses. This information only applies to shipboard work described in this Proceedings volume; methods used in shore-based analyses of Expedition 351 samples and/or data will be described in various scientific contributions in the open peer-reviewed literature and the Expedition research results section of the volume.

Site location

Site U1438 was chosen because we expected (1) remnants of drillable oceanic crust that existed in the region immediately before arc inception, (2) preservation of the initial Izu-Bonin-Mariana (IBM) magmatic record, including geological evidence for inferring the tectonic setting at subduction initiation, and (3) preservation of the temporal variations of magmatism in the rear IBM arc as a sequence of volcaniclastic sediments and tephra.

Once arriving at the site, the ship’s thrusters were lowered and a positioning beacon was dropped to the seafloor. The vessel used a Neutronics 5002 dynamic positioning system with input from the GPS system and triangulation to the seafloor beacon to remain on site. Final hole positions were averages calculated from GPS data collected over a significant period of time while the hole was occupied. Full operational details from Site U1438 can be found in Operations in the Site U1438 chapter (Arculus et al., 2015).

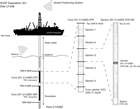

Site, hole, core, and sample numbering

Numbering of the site, holes, cores, and samples followed standard IODP protocol (Figure F1). Drilling sites have been numbered consecutively from the first site drilled by the Glomar Challenger in 1968, and since Expedition 301 the prefix “U” has been used to designate sites cored by the U.S. research vessel JOIDES Resolution. At a site, multiple holes are often drilled, and a letter suffix distinguishes the holes drilled at one site. For example, the first hole would be given the suffix “A,” the second “B,” and so on. During Expedition 351, a letter designation applied to each cored hole (including one jet-in test) and a dedicated logging hole.

Following the hole designation, each recovered core was numbered sequentially. A cored interval is generally ~9.5 m maximum, which is the length of a standard core barrel. However, the half-length advanced piston corer (APC) system employs a core barrel of ~4.7 m. The specific coring system used to recover a core is designated by a letter representing the core type and is a suffix to the core number: H = APC, F = half-length APC, X = extended core barrel (XCB), and R = rotary core barrel (RCB). All of these systems were utilized during Expedition 351.

Each recovered core was cut into ~1.5 m sections. The number of sections is determined by core recovery, and sections are numbered sequentially starting with “1” at the top of the core. Each core is eventually split lengthwise into working- and archive-half sections (described below) designated by either the letter “W” or “A” succeeding the core number. For depth calculations (see below), the top depth of the core is equated with the top depth of the cored interval (in meters below seafloor [mbsf]) to achieve consistency in handling analytical data derived from the cores. Sample intervals are described in centimeters within a core section (typically between 0 and 150 cm) beginning from the top of the core section.

Thus, the full curatorial identifier of a sample consists of the following: expedition, site, hole, core number, core type, section number, section half, piece number (hard rocks only), and interval in centimeters measured from the top of the core section (Figure F1). For example, a sample identified as “351-U1438D-37R-4W, 50–55 cm” represents a 5 cm interval from the fourth section (working half) of Core 37R (cored with the RCB system) from Hole D of Site U1438 during Expedition 351.

Sample depth calculation

During Expedition 351, the cored interval was measured in meters below seafloor as determined by core depth below seafloor, method A (CSF-A). The calculation of this depth scale is defined by protocol (see IODP Depth Scales Terminology at www.iodp.org/program-policies). In general, the depth below seafloor is determined by subtracting the initial drill pipe measurement to the seafloor from the total drill pipe measurement. The core depth interval begins with the depth below seafloor where coring began and extends to the depth that coring advanced. However, if a core has incomplete recovery (<100%), all material is assumed to originate from the top of the cored interval as a continuous section for curation purposes (Figure F1); thus, the true depth interval within the cored interval is unknown and represents a sampling uncertainty in age-depth analysis or correlation with downhole logging data.

Additionally, wireline log depths were calculated from the wireline log depth below seafloor (WSF) and are also reported in meters below seafloor. When multiple logging passes were made (see Downhole measurements), the wireline log depths are matched to one reference pass, creating the wireline log matched depth below seafloor (WMSF). These distinctions in nomenclature between core (curated) and wireline log depth should be noted because the same depth value from different scales does not necessarily refer to the same stratigraphic interval.

Core handling and analysis

Core handling and flow are depicted in Figure F2.

Sediment

Immediately upon arriving on deck, core catcher samples were taken for biostratigraphic analyses. The cores were then cut into 1.5 m sections, after which whole-round samples were taken for shipboard interstitial water measurements and noted by the use of a yellow end cap. Additional samples taken on the catwalk include syringe samples for routine hydrocarbon gas safety monitoring, samples for postcruise microbiological studies, and samples for postcruise redox-sensitive element analyses (see Geochemistry). After the cores equilibrated to laboratory temperature (~4 h), they were run through the Whole-Round Multisensor Logger (WRMSL) for P-wave velocity, magnetic susceptibility, and bulk density measurements, as well as the Natural Gamma Radiation Logger (NGRL). Thermal conductivity measurements were also made when the samples were unconsolidated sediments (see Physical properties).

The core sections were then split lengthwise into archive- and working-half sections. Oriented pieces of more indurated sediments were marked on the bottom with a red wax pencil.

Hard rock

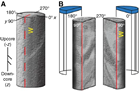

During Expedition 351, cores from the igneous basement were curated as hard rock. On the catwalk, pieces were pushed to the bottom of the sections and the total length was measured as “recovered length,” which was used to calculate recovery. The sections were then brought into the core splitting room, where oriented pieces of core were marked with a wax pencil. In several cases, pieces were too small to be oriented with certainty. Pieces in a section were placed into sample bins separated by plastic core spacers. The plastic spacers were also used to indicate areas of no recovery. Adjacent pieces that could be fit back together were curated as single pieces. Once completed, a designated scientist (usually the paleomagnetist on shift) confirmed the piece matches and drew split lines indicating where/how the pieces should be cut into archive and working halves. The split lines ideally maximized the expression of dipping surfaces on the cut face of the core while preserving representative features in the archive and working halves (Figure F3).

Once the split lines were drawn, the spacers were secured in place with acetone in both archive- and working-half core liners with the angle brace facing uphole. This ensured that the curated interval for each bin matched the top of each piece. The length of each bin was entered into SampleMaster as “bin length,” and the sum of a section’s bin lengths was entered as “curated length.” Additionally, the length of each piece was measured along the longest vertical dimension and entered as “piece length” (Figure F4). Following this, the empty core liner half was placed over the full half and taped together in several places. The cores were allowed to dry and equilibrate to laboratory conditions (~3 h).

The sections were then run through the WRMSL and NGRL before being carefully split into archive and working halves. Piece halves were numbered sequentially from the top of each section, and reconstructed groups of pieces in the same bin were assigned the same number but lettered sequentially. If a piece was oriented with respect to vertical, an arrow pointing to the top of the section was added to the label.

For both sediment and hard rock cores, the working-half sections were used for taking discrete shipboard samples for paleomagnetic, physical properties, geochemical, and thin section analyses (for details, see the individual laboratory group methods in this chapter), as well as science party personal samples for postcruise research. Sampling for postcruise research was based on the sampling plan agreed upon by the science party and the Sample Allocation Committee.

The archive-half core sections were run through the Section Half Imaging Logger (SHIL) and the Section Half Multisensor Logger (SHMSL) for color reflectance and point magnetic susceptibility measurements. The archive halves were described by expedition scientists visually and by smear slide and thin section analyses. Finally, they were measured with the cryogenic magnetometer.

All instrument data from Expedition 351 were uploaded into the IODP Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS), and core description observations were entered using the DESClogik application. DESClogik is an interface used to input visual (macro- and/or microscopic) core descriptions on a core (sediment) or section (igneous basement) scale to be stored in LIMS.

When all shipboard measurements were completed, data uploaded, and samples taken, the cores were wrapped, sealed in plastic, and transferred to cold storage on the ship. At the end of the expedition, the cores were transferred into refrigerated trucks and transported to cold storage at the IODP Kochi Core Center in Kochi, Japan.

Core sample disturbance

Core material has the potential to be disturbed and/or contain extraneous material as a result of the coring process or core handling and analysis. In less consolidated sections, material from intervals shallower in the hole may be washed down by drilling circulation and accumulate at the bottom of the hole; they then are sampled with the recovery of the next core. This is referred to as “fall-in.” In most Expedition 351 cores, there was very little evidence of fall-in, but when present, it affected the upper ~10–20 cm of the cores. Additionally, common coring deformation includes concave appearance of originally horizontal bedding. In more consolidated material, biscuiting is a common core disturbance, where fractured material (“biscuits”) spin within the core barrel. In many cases, drilling slurry can be interjected between the biscuits. Finally, fracturing, fragmentation, and brecciation as a result of the drilling process are also common drilling-induced disturbances. The occurrences of these disturbance types are described in Lithostratigraphy in the Site U1438 chapter (Arculus et al., 2015) and graphically represented on the visual core descriptions (VCDs) (see Core descriptions).

Authorship of methods and site chapters

The sections of the methods and site chapters were written by the following scientists (in alphabetical order):

- Background and objectives: Arculus, Ishizuka

- Operations: Bogus

- Lithostratigraphy: Barth, Brandl, Hickey-Vargas, Jiang, Kanayama, Kusano, Li, Marsaglia, McCarthy, Meffre, Savov, Tepley, Yogodzinski

- Biostratigraphy and paleontology: Aljahdali, Bandini, Guerra, Kender

- Geochemistry: Loudin, Sena, van der Land, Zhang

- Paleomagnetism: Maffione, Morris

- Physical properties: Drab, Gurnis, Hamada

- Downhole measurements: Drab, Gurnis, Hamada, Neuhaus

Lithostratigraphy

Core description process

During Expedition 351, sediments and rocks were described by a team with diverse backgrounds in igneous petrology, volcanology, and volcaniclastic and nonvolcanic sedimentology. Macroscopic descriptions of the core were made on the archive halves of split cores. Observations were tabulated on printouts of high-resolution images from the Section Half Imaging Logger (SHIL) and entered into the LIMS database using DESClogik software. Smear slides and petrographic thin sections were made for selected intervals and described using polarized light microscopy (transmitted and reflected light). Petrographic observations were entered into the LIMS database using DESClogik. Microscopic observations apply rigorously only to the intervals where a smear slide or thin section was made, which is indicated on the visual core descriptions (VCDs).

Core description data are available through the “Descriptive Information” LIMS report (web.iodp.tamu.edu/DESCReport). Standard graphic reports were generated from data downloaded from the LIMS database to summarize each core (typical for sediments) or section half (typical for igneous rocks). A sample VCD is shown in Figure F5. Legends for symbols used on the VCDs are shown in Figures F6, F7, and F8.

Sediment and sedimentary rock classification scheme

Pelagic/hemipelagic and volcaniclastic sediments and sedimentary rocks were the principal sedimentary materials recovered during Expedition 351. The sedimentary classification scheme that was employed emphasizes important descriptors for those sediments and rocks, particularly descriptors that can be quantified and recorded in DESClogik in the same time frame as shipboard core description (“Macroscopic” template, “Sediment” tab). A schematic of the description parameters and scheme is shown in Figure F9.

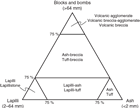

Sediments and sedimentary rocks were classified using an approach that integrates volcanic particles into the sedimentary descriptive scheme typically used by IODP. In our scheme, sediments and sedimentary rocks are divided into four lithologic classes, based on composition (types of particles):

- Volcaniclastic sediment and rocks of pyroclastic origin, containing >75% volcanic particles;

- Tuffaceous volcaniclastic sediment and rocks of sedimentary origin, containing 25%–75% volcanic-derived particles;

- Siliciclastic sediment and sedimentary rocks, containing <25% volcanic siliciclastic particles and <5% biogenic particles; and

- Pelagic to hemipelagic sediment (rock), containing <25% volcanic particles and >5% biogenic particles.

Examples from each of these four lithologic classes were encountered during this expedition. Within each class, the principal lithology name is based on particle size. In addition, appropriate prefixes and suffixes were chosen; for example, the prefix “tuffaceous” was used for the tuffaceous lithologic classes, and prefixes that indicate the dominant biogenic component, determined by microscopic examination, were used for pelagic/hemipelagic sediment and sedimentary rocks. Suffixes were also chosen to indicate minor components within a principal lithologic type.

Principal lithology names

Principal names for sediments and sedimentary rocks of the tuffaceous, nonvolcanic siliciclastic, and pelagic/hemipelagic lithologic classes are adapted from the grain size classes of Wentworth (1922). Principal lithology names for sediment and sedimentary rocks of the pyroclastic lithologic class were adapted from the grain size classes of Fisher and Schmincke (1984) (Table T1). For each grain size class, both a consolidated (semilithified to lithified) and a nonconsolidated term exists; they are mutually exclusive (e.g., mud or mudstone; ash or tuff). For simplicity, Wentworth’s clay and fine silt sizes are combined in a “mud” class; similarly, very fine, fine, medium coarse, and very coarse sand are combined in “fine sand,” “sand,” and “medium to coarse sand” (stone) classes. Silt/siltstone is also used independently.

Table T1. Particle size nomenclature and classifications. Download table in .csv format.

The grain size terms granule, pebble, and cobble (Wentworth, 1922) in lithified sediments are replaced by breccia, conglomerate, and breccia-conglomerate (Table T1). A conglomerate is defined as a rock where the fragments are >2 mm and are exclusively (>95 vol%) rounded and subrounded (Figure F10). A breccia-conglomerate is composed of predominantly rounded and/or subrounded clasts (>50 vol%) and subordinate angular clasts. A breccia is predominantly composed of angular clasts (>50 vol%). For the equivalent pyroclastic lithologic class, the term “agglomerate” would be used in place of conglomerate (Fisher and Schmincke, 1984) (Figure F11). Irrespective of the sediment or rock lithologic class, the average and maximum grain size reported in the VCDs follow Wentworth (1922). For example, an ash can be further described as sand-sized ash or silt-sized ash, whereas a lapilli-tuff can be described as coarse sand sized or pebble sized.

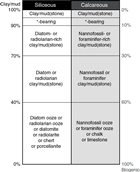

For pelagic and hemipelagic sediments (the nonvolcanic siliciclastic and biogenic classes, 3 and 4 above), a modified version of the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Leg 126 sediment classification scheme was used (Figure F12; Table T1) (Taylor, Fujioka, et al., 1990). Our modified classification uses composition and grain size as the only criteria to define sediment and rock types. The principal lithology name is based on induration and on average grain size as determined macroscopically, supplemented at selected intervals with smear slide observations of the identity and abundances of biogenic particles. For sediments and rocks with <60% biogenic material, the principal name is determined by the relative proportions of nonbiogenic sand-, silt-, and clay-sized particles. If the biogenic component exceeds 60%, the principal name is ooze or an appropriate term that denotes the sediment induration, for example, chert and chalk or limestone.

Prefixes

Prefixes were used to indicate the lithologic class of sediment or sedimentary rocks. For pelagic/hemipelagic sediments and sedimentary rocks with 25%–60% biogenic material, prefixes were added to indicate the type and quantity of fossil material, using the classification scheme shown in Figure F12. In this case, prefix categories were based on the percentage of microfossils seen in smear slides taken at selected intervals. For sediments and rocks with 5%–25% biogenic material, either a prefix or suffix was added (see below) to indicate the presence of microfossils as a minor component. Other prefixes may be selected in combination with those for the pyroclastic and tuffaceous lithologic classes. These prefixes are primarily used for sedimentary rocks having clasts (i.e., particles >2 mm) that can be examined by macroscopic observation. The term “monomict” applies to clast compositions of a single type, and “polymict” applies to clast compositions of multiple types. The term “matrix-supported” was used where smaller particles visibly envelop each of the larger particles. In this usage, the word “matrix” is not defined by a specific grain size (e.g., conglomerate may have a sandstone matrix, and sandstone may have a mudstone matrix). The term “clast-supported” was used where clasts form a sediment framework.

Suffixes

A suffix was used for a subordinate but important component that deserved to be highlighted. Suffixes are restricted to a single phrase to maintain a short and effective lithology name containing the most important information only. They are in the form “with ash,” “with clay,” or “with foraminifers” in cases where abundance is between 5% and 25%.

Thin section description of sedimentary rocks

Because of their importance in Expedition 351 cores, a systematic approach was implemented in DESClogik to record microscopic characteristics of volcaniclastic sedimentary rocks (“Microscopic” template, “Sediment TS” tab). The system provides a framework for recording data for both texturally complex (clast-bearing) coarse-grained rocks and less complex lithologies dominated by finer grain sizes (sand, silt, and mud). For tuffaceous breccia-conglomerates and other clast-bearing lithologies, the system provides the opportunity to record modal data for two types of whole-rock matrix and up to five separate clast types. Each matrix or clast type is assigned a domain type and number and is entered on a separate row in DESClogik. Modal components available under the matrix category are minerals, which occur as matrix grains, with additional options such as ash, clay, pumice, scoria, lithics, carbonate, and authigenic mineral (secondary) components. Modal components available under the clast category include the same list of minerals, which occur as phenocrysts, plus groundmass, vesicles, and secondary minerals, which make up the remaining portion of the mode for most volcanic clasts.

Each clast is also assigned the following:

- Grain size category (e.g., granule, pebble, or cobble),

- Clast type, selected from a list of rock names,

- Texture (porphyritic, aphyric, or tuffaceous), and

- Alteration category (absent/fresh, slight, moderate, or high).

The modes for each matrix and clast should total 100%. For texturally simple rock types of more uniform grain size, such as tuffaceous sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone, the pertinent microscopic information is entered into DESClogik as a single matrix domain. An Excel spreadsheet form was developed to facilitate recording of thin section observations by hand (Figure F13). The data on this form was then entered into DESClogik.

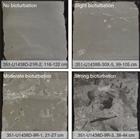

Other parameters

Average and maximum particle size, sediment sorting and grading, the characteristics of bedding planes, the extent of bioturbation, and the presence of sedimentary structures are additional elements that were recorded in macroscopic core descriptions (Figures F10, F14; Table T2). Coring disturbances were also noted and recorded. Disturbance types are primarily brecciation, fracturing, and biscuiting, with some other types as summarized in Figure F15.

Table T2. Bed thickness classifications. Download table in .csv format.

Secondary minerals in sediments and sedimentary rocks

Secondary mineral development in Site U1438 sediments and sedimentary rocks was documented through smear slide, thin section, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) observations. Smear slide and thin section sample preparation steps followed standard and widely accepted practices. Smear slide and petrographic observations of secondary minerals are recorded in both the macroscopic and microscopic areas of DESClogik.

Samples for XRD analysis were freeze-dried for 12 h and then crushed using an agate mortar and pestle. No additional sample preparation steps were taken to aid identification of clay or zeolite mineral species. Diffraction data were generated on the JOIDES Resolution shipboard Bruker D4Endeavor X-ray diffractometer using a generator voltage of 35 kV and current of 40 mA. We collected continuous scans from 4° to 75°2θ for 4276 steps at a rate of 1 s/step. We evaluated diffraction data against the International Center for Diffraction Data database for minerals using the Search/Match component of Bruker’s EVA Diffraction Evaluation software. The diffractogram of a typical sample was usually accounted for by the presence of three to six common minerals or minerals known to be present or considered likely to be present in the samples, based on geologic context and thin section or smear slide observations.

Unit determinations

Sediments and sedimentary rocks, including volcaniclastic, siliciclastic, and biogenic types, were described at the level of (1) the descriptive interval (a single descriptive line in the DESClogik spreadsheet) and (2) the lithostratigraphic unit. A descriptive interval (Table T3) is unique to a specific depth interval and typically consists of a single sediment or rock type distinct from those immediately above and below it, for example, a tuff interval intercalated between mudstone intervals. Less commonly, the same sediment or rock type may be repeated in consecutive descriptive intervals if one or more characteristics differ between them, for example, a planar laminated tuffaceous siltstone below or above cross-laminated tuffaceous sandstone.

Table T3. Definition of lithostratigraphic units, descriptive intervals, and domains. Download table in .csv format.

Lithostratigraphic units are meter-thick to hundreds of meters–thick assemblages of multiple descriptive intervals containing similar sediment or rock types (Table T3). They are numbered sequentially (Unit I, Unit II, etc.) from top to bottom. Lithostratigraphic units are clearly distinguishable from each other by several characteristics, such as composition, bed thickness, grain size class, and internal homogeneity. Lithostratigraphic units are, therefore, informal formations that are not defined by age, geochemistry, or paleontology, although changes in these parameters may coincide with boundaries between lithostratigraphic units.

Sedimentary rock structure and measurement

The methods used during Expedition 351 for documenting the structural geology were simplified from those used during Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 344 (Harris et al., 2013). We documented deformation that was observed on the archive half of the split cores by classifying structures, measuring orientation data, and recording the sense of displacement. These data were logged at the core table and entered into DESClogik under the “Structure” tab or as comments for the interval (for millimeter- to centimeter-scale structures within the interval).

Igneous rocks

Igneous rock description procedures during Expedition 351 generally followed those of IODP Expedition 350, Expedition 344, and other Integrated Ocean Drilling Program and IODP expeditions that encountered volcanic units (e.g., Expedition 350 Scientists, 2014; Expedition 330 Scientists, 2012; Expedition 336 Scientists, 2012; Expedition 340 Scientists, 2013; Harris et al., 2013). Macroscopic observations were coordinated where possible with thin section or smear slide petrographic observations and bulk-rock chemical analyses of representative samples. Data for the macroscopic and microscopic descriptions of recovered cores were entered into the LIMS database using DESClogik. Volcanic rock characteristics were entered through the “Extrusive hypabyssal” tab, and plutonic rocks were entered through the “Intrusive mantle” tab.

Macroscopic descriptions of volcanic rocks recovered during Expedition 351 were entered into the “Macroscopic” template’s “Extrusive hypabyssal” tab. Volcaniclastic sediments that contain igneous particles of various sizes were recovered, for the most part with grain sizes <2 cm; for these sediments, microscopic clast descriptions were entered using the “Microscopic” template’s “Sediment TS” tab, as described in Thin section description of sedimentary rocks. Igneous clasts >2 cm in size and basement volcanic rocks were described using the “Microscopic” template’s “Extrusive hypabyssal” tab.

Volcanic (extrusive hypabyssal) rocks: principal lithology name and descriptive parameters

For macroscopic description of volcanic rocks, we use a simplified classification scheme based on visual characteristics. The lithology name consists of a principal name and optional suffix (Table T4). The principal name depends on the nature of phenocrysts, when present, and/or the color of the groundmass. Three rock categories are defined:

- Basalt: black to dark gray rock containing plagioclase and pyroxene.

- Andesite: dark to light gray rock containing pyroxenes and/or feldspar and/or amphibole and typically devoid of olivine and quartz.

- Rhyolite/dacite: light gray to pale white rocks, usually plagioclase-phyric, and sometimes containing quartz ± biotite.

Table T4. Nomenclature for macroscopic and microscopic description of extrusive and hypabyssal volcanic rocks. Download table in .csv format.

The suffix indicates the nature of the volcanic body: lava, pillow lava, intrusive sheet, or clast. The suffix “hyaloclastite” or “breccia” is used if the rock occurs in direct association with related in situ lava (Table T4). Prefixes are not used for macroscopic description.

Other descriptive parameters that are recorded are rock texture (see below), grain size, phenocryst type and abundance, vesicularity and vesicle shape, secondary minerals, and the nature of contacts between volcanic rock intervals.

Microscopic descriptions are similar to macroscopic observations but are more detailed. Seven primary rock types are defined (basalt, boninite, dolerite, basaltic andesite, andesite, dacite, and rhyolite) (Table T4). Optional suffixes indicate the nature of the volcanic rock body. Phenocryst type, modal abundance, and modal grain size are recorded, together with other parameters used for macroscopic description.

Plutonic (intrusive mantle) rocks: principal lithology name and descriptive parameters

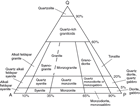

Plutonic rocks are classified according to the International Union of Geological Sciences classification scheme of Le Maitre et al. (2002). The nature and proportion of minerals are used to give a principal lithology name to the sample. Leucocratic rocks dominated by quartz and feldspar are named using the quartz-alkali feldspar-plagioclase (QAP) diagram (Figure F16). For melanocratic plutonic rocks, we used the plagioclase-clinopyroxene-orthopyroxene and olivine-pyroxene-plagioclase triangular plots (Figure F17). In all, 22 principal lithology names are used. Three suffixes, banded, layered, and foliated, may be used to identify macroscopic rock features. Rock texture, overall grain size, modal abundance, and modal grain size of mineral types and intrusive rock contact types are recorded.

Microscopic descriptions are similar to macroscopic observations but are more detailed. A larger list of descriptive suffixes is used, and more options are used for definition of rock texture; maximum grain size and grain size distribution are added characteristics. Constituent minerals are described with modal abundance and modal and maximum grain size.

Igneous texture definitions

Textures are described macroscopically for all igneous rock core sections and microscopically for the subset of intervals having thin sections. Macroscopic textural descriptions applied to volcanic/hypabyssal rocks are holocrystalline, porphyritic, trachytic, flow banding, perlite, glassy matrix, glassy, quench margin, and glomeroporphyritic.

For intrusive/mantle rocks, textural descriptors are

- Equigranular (principal minerals are in the same size range),

- Inequigranular (principal minerals have different grain sizes),

- Porphyritic,

- Poikilitic (larger crystals enclose smaller grains),

- Ophitic (pyroxene encloses plagioclase laths), and

- Subophitic (pyroxene partially encloses plagioclase laths).

In addition, for microscopic descriptions, cryptocrystalline (<0.1 mm) is used.

Prefixes used in microscopic textural descriptions are (Wilcox, 1954)

Glomeroporphyritic texture refers to clusters of phenocrysts.

Magmatic flow textures are described as trachytic when plagioclase laths are subparallel.

Perlite describes rounded hydration fractures in glass.

Quenched margin texture describes a glassy or microcrystalline margin to an otherwise coarser grained interior.

Vesicularity is described according to proportions:

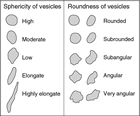

For microscopic observations, the modal size and sphericity of vesicle populations are estimated using appropriate comparison charts, following Expedition 330 Scientists (2012) (Figure F18).

Secondary minerals in igneous rocks

Alteration features in igneous rocks from Expedition 351 are based on macroscopic observations of core, aided by shipboard smear slide, thin section, and XRD and inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) investigations. Secondary minerals in cores were recorded in DESClogik in the macroscopic template under separate tabs for alteration, veins, and halos.

Levels of alteration in groundmass were recorded as

Textures used to define groundmass alteration were patchy, corona, pseudomorphic, and recrystallized.

Colors used to define alteration are black, brown, gray, green, white, and yellow.

Groundmass, glass, and mineral replacement minerals and vesicle filling minerals are classified as dominant, second order, and third order.

Alteration of groundmass includes major mineral products amphibole, biotite, carbonate, chalcedony, chlorite, clay, epidote, feldspar (albite), glauconite, oxide, quartz, sulfide, zeolite, or unknown when the mineral cannot be identified.

Alteration of phenocryst minerals includes iddingsite, prehnite, sericite, serpentine, and talc.

Vesicle-filling minerals include calcite, carbonate, chalcedony, zeolite, clay, chalcopyrite, sulfide, chlorite, prehnite, and unknown and undefined mineral.

Microscopic observations of alteration minerals in igneous rocks are similar but more detailed. Percentages of individual replacement minerals are estimated for each phenocryst mineral, groundmass, and glass.

Descriptions of veins and halos record their mineralogy, geometry, contacts, and crosscutting relationships with the host rock(s).

Vein texture selections are vuggy, cataclastic, saccharoidal, sutures, patchy, banded, comb-structured, overgrowths, fibrous, and brecciated.

Vein geometry selections are splayed, sinuous, irregular, planar, and curved.

Vein contacts may be gradational, sharp-to-gradational, sharp, sutured, and diffuse.

Vein connectivity is described as networked, anastomosing, branched, and isolated.

Vein and halo minerals are described as dominant, second order, and third order.

Unit designations

Igneous rocks are described at the level of the descriptive interval (the individual descriptive line in DESClogik), which ultimately is the lithostratigraphic unit level. A descriptive interval consists of variations in rock characteristics, such as vesicle distribution, igneous textures, mineral modes, and chilled margins. Samples within the volcanic category are massive lavas, pillow lavas, intrusive sheets (i.e., dikes and sills), and volcanic breccias intimately associated with lava flows. Breccias not associated with lava flows and hyaloclastites not associated with pillow lavas are described on the sediment form in DESClogik.

Massive lava is defined as a coherent volcanic body with a massive core and vesiculated (sometimes brecciated or glassy) flow top and/or bottom. Intrusive sheets are defined as dikes or sills cutting across other volcanic bodies. They frequently have holocrystalline groundmass and nonvesiculated chilled margins along their boundaries. Their size varies from several millimeters to several meters in thickness.

Description of workflow

The core description workflow included the following steps:

- Initial determination of intervals in a core section based on macroscopic observation of particle/grain sizes, compositional changes and heterogeneity, igneous and sedimentary structures, and characteristics of contacts.

- Microscopic analyses performed on selected intervals using (a) sediment smear slides or (b) petrographic thin sections.

- Classification of the rock intervals based on macroscopic parameters and microscopic analyses, when available.

- Descriptive summary of the core.

- Integration with XRD and carbonate analyses to verify or correct mineralogical identification.

Biostratigraphy

Paleontological investigations and biostratigraphic determinations during Expedition 351 were carried out on calcareous nannofossils, planktonic and benthic foraminifers, and radiolarians. We followed the Cenozoic planktonic foraminifer biozonation scheme of Wade et al. (2011). Species identification was primarily based on Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Pearson et al. (2006), and Bolli and Saunders (1985). Benthic foraminifer species determination was largely carried out with reference to Kaiho (1992), van Morkhoven et al. (1986), and Holbourn et al. (2013). The standard zonations of Martini (1971) and Okada and Bukry (1980) were used for Cenozoic nannofossil biostratigraphy. The identification of calcareous nannofossils during this expedition followed the taxonomy of Perch-Nielsen (1985), Varol (1998), and Young (1998). The radiolarian low-latitude zonation used during the expedition was based on Sanfilippo et al. (1985) and Sanfilippo and Nigrini (1998). For radiolarians, the primary references for taxonomic identification were Sanfilippo et al. (1985), Hollis (2006), and Jackett et al. (2008). All ages cited in the text and figures for each of the microfossil groups are based on calibration with the timescale of Gradstein et al. (2012). All data were recorded in DESClogik and uploaded to the LIMS database.

Core catcher (CC) samples from all cores were examined. Additional samples were taken from the working-half section as necessary to refine the biostratigraphy, preferentially sampling hemipelagic intervals.

Foraminifers

Sediment volumes of approximately 20 cm3 were collected for analysis of both benthic and planktonic foraminifers. All samples were washed with water over a 63 µm mesh sieve and dried in an oven at ~70°C. Samples that were more lithified were soaked in warm (70°C) water with sodium borate (Borax) for several hours prior to wet sieving. For the most lithified samples, a freeze-thaw method with kerosene was used (adapted from Hermann [1992] and Kennedy and Coe [2014]). The samples were placed in sample bags and broken with a plastic hammer, soaked in water for more than 1 h, and then placed in a freezer at –80°C for several hours. Boiling water was poured over the residue, which was then washed with water over a 63 µm sieve. The residue was placed in a freeze-drier for approximately 24 h to clear the pore spaces and then soaked in kerosene for 24 h. The kerosene was decanted, and the sample was left to soak in deionized water for several minutes before sieving. The water replacement of the kerosene in pore spaces creates pressure that helps disaggregate the clay (Hermann, 1992). All dry coarse fractions were placed in a labeled vial ready for micropaleontological examination.

Examination of foraminifers was carried out on the >150 µm size fraction following dry sieving. The sample was spread over a sample tray and examined for planktonic and benthic foraminifers. The size fraction <150 µm was examined in parts of the record when datum species of smaller sizes were expected. A visual assessment of group and species relative abundances was made, along with their preservation according to the categories defined below. Photomicrographs were taken using a Spot RTS system with IODP Image Capture and commercial Spot software and using a Hitachi TM3000 tabletop scanning electron microscope (SEM).

The relative abundance of both planktonic and benthic foraminiferal species in the biogenic fraction >150 µm was estimated as follows:

The proportion of either planktonic or benthic foraminifer specimens in each slide (>150 µm) was estimated as follows:

- Barren = no foraminifers present.

- Present = <1%.

- Rare = 1%–5%.

- Few = 5%–10%.

- Common = 10%–30%.

- Abundant = >30%.

Preservation of planktonic and benthic foraminiferal assemblages was estimated using the following categories:

- G = good (>90% of specimens unbroken with only minor evidence of diagenetic alteration; diagnostic characteristics fully preserved).

- M = medium (30%–90% of specimens are unbroken; dissolution and/or secondary overgrowth present).

- P = poor (strongly recrystallized or dominated by fragments and broken or corroded specimens).

Calcareous nannofossils

Calcareous nannofossils were examined in smear slides prepared directly from unprocessed samples using standard techniques. The slides were analyzed between crossed polars (PPL), phase contrast, and between crossed polars (XPL) using a Zeiss Axiophot light microscope at a magnification of 1000×. One traverse (~100 fields of view) was used to estimate relative abundance and to ensure rare species were recorded. For coarse material, the fine fraction was separated from the coarse fraction by settling through water before the smear slide was prepared. Photomicrographs were taken using a Spot RTS system with the IODP Image Capture and Spot commercial software.

The overall and individual nannofossil abundances were determined using the following criteria:

- B = barren (no nannofossils).

- R = rare (1 specimen per >10 fields of view).

- VF = very few (1 specimen per 2–10 fields of view).

- F = few (2–10 specimens per 2–10 fields of view).

- C = common (1–10 specimens per field of view).

- A = abundant (11–100 specimens per field of view).

- V = very abundant (>100 specimens per field of view).

- * = reworked occurrence.

The following basic criteria were used to qualitatively provide a measure of preservation of the nannofossil assemblage:

- E = excellent (no dissolution is seen; all specimens can be identified).

- G = good (little dissolution and/or overgrowth is observed; diagnostic characteristics are preserved and all specimens can be identified).

- M = moderate (dissolution and/or overgrowth are evident; a significant proportion [up to 25%] of the specimens cannot be identified to species level with absolute certainty).

- P = poor (severe dissolution, fragmentation, and/or overgrowth has occurred, most primary features have been destroyed, and many specimens cannot be identified at the species level).

Radiolarians

Radiolarian assemblages were examined and described from all core catcher samples and from selected additional samples. Lithified samples were initially crushed with a hammer into millimeter-sized fragments. All samples were then disaggregated in a warm (70°C) solution of 10% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to remove any organic material, with the addition of a squirt of Borax, which acts as a clay dispersant. After effervescence, samples were sieved and washed through a 63 µm mesh. Residues of more lithified samples were returned into a beaker with a similar solution, sieved, and washed a second time. If calcium carbonate was evident, a 10% solution of hydrochloric acid (HCl) was added after effervescence decreased to dissolve the calcareous fraction. A portion of the residue was placed with a pipette directly onto a glass microscope coverslip. The coverslip was then dried on a hot plate. After drying but while still warm, the coverslip was gently mounted onto a glass microscope slide with Norland optical adhesive (Number 61) and placed under an ultraviolet lamp for about 10 min. Strewn slides were examined using a Zeiss Microscope (Model AX 10) coupled with a Diagnostic Instruments (Model 15.2 64 Mp Shifting Pixel) photomicrograph camera system.

When radiolarian skeletons were recrystallized as quartz, clay minerals, or zeolites filled by matrix or cement, they could not be examined using standard transmitted-light techniques. These residues were sieved, dried, and examined using reflected-light methods and a Hitachi TM3000 tabletop scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Total abundances of radiolarian assemblages on a slide were estimated using the following categories:

- B = barren (absent).

- R = rare (>0–500 specimens per slide).

- F = few (>500–2,000 specimens per slide).

- C = common (>2,000–10,000 specimens per slide).

- A = abundant (>10,000 specimens per slide).

Abundances of individual taxa per sample were estimated using the following categories:

- ?r = possibly reworked.

- R = rare (1% or less of slide).

- F = few (>1%–5% of slide).

- C = common (>5%–15% of slide).

- A = abundant (>15%–30% of slide).

- D = dominant (>30% of slide).

Preservation of the radiolarian assemblage was estimated using the following categories:

- G = good (most specimens complete; fine structures preserved).

- M = moderate (minor evidence of dissolution and/or breakage).

- P = poor (common crystal overgrowth, dissolution, and/or breakage).

Geochemistry

Shipboard geochemical analyses were performed on samples from Holes U1438A, U1438B, U1438D, and U1438E. These analyses included inorganic chemical analysis of the interstitial water present in the pores and fractures of the cored sediments and rocks, hydrocarbon analysis of headspace gas, and organic and inorganic chemical analysis of the solid matrix.

Headspace analysis of hydrocarbon gases

One sample per sediment core was routinely taken for headspace hydrocarbon gas analysis as part of the standard shipboard safety monitoring procedure as described in Kvenvolden and McDonald (1986) and updated by Pimmel and Claypool (2001). Regular shipboard monitoring of the hydrocarbon content of the cores ensured an assessment of the probable risks of an uncontrolled release of hydrocarbons while drilling.

A 5 cm3 sediment sample was collected from the core immediately after sectioning on deck, placed in a 20 cm3 glass vial, and sealed with a Teflon/silicon septum and a crimped aluminum cap. During Expedition 351, the location of the headspace sample was typically taken at the top of Section 4 (Figure F19). A 5 cm3 aliquot of the evolved hydrocarbon gases was extracted from the headspace vial with a standard gas syringe and then manually injected into an Agilent/Hewlett Packard 6890 Series II gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector set at 250°C. The column (2 mm inner diameter; 6.3 mm outer diameter) was packed with 80/100 mesh HayeSep (Restek). The gas chromatograph oven program remained at 80°C for 8.25 min, was taken to 150°C at 40°C/min, and then was kept isothermal for 5 min, resulting in a total run time of 15 min.

Results were collected using the Hewlett Packard 3365 ChemStation data processing software. The chromatographic response was calibrated with nine different gas standard analyses and checked daily. The concentration of the analyzed hydrocarbon gases was reported as parts per million volume (ppmv).

Interstitial water analyses

Sampling

A whole-round core sample was taken immediately after core sectioning on deck, typically at the bottom of Section 3, for the subsequent extraction of interstitial water (IW) in the Geochemistry laboratory (Figure F19). The length of the whole-round core taken for IW analysis varied from 5 cm in the upper sediments, where the extracted volume of IW was enough for performing the shipboard analyses, to 20 cm in the deeper sediments and rocks, where the volume of extracted IW was more limited.

The whole-round samples collected were processed under atmospheric conditions. After extrusion from the core liner, contamination from seawater and sediment smearing was removed by scraping the core surface with a spatula. In APC cores, ~0.5 cm of material from the outer diameter and the top and bottom faces was removed, whereas in XCB and RCB cores, where borehole contamination is higher, as much as two-thirds of the sediment was removed from each whole round. The remaining inner core (~150–300 cm3) was placed into a titanium squeezer (modified after Manheim and Sayles, 1974) and compressed using a laboratory hydraulic press to extract the interstitial pore water, using a total pressure <20 MPa.

The IW extracted from the compressed sediment sample was filtered through a prewashed Whatman No. 1 filter situated above a titanium mesh screen. Approximately 20 mL of IW was collected in precleaned plastic syringes attached to the squeezing assembly and then filtered through a Gelman polysulfone disposable filter (0.45 µm). In deeper sections, IW recovery was as low as 5 mL after squeezing the sediment for as long as ~2 h. After extraction, the squeezer parts were cleaned with shipboard water, rinsed with deionized water, and dried thoroughly prior to the next use. Sample allocation was determined based on the IW volume recovered and analytical priorities based on the expedition objectives.

Shipboard IW analyses

IW samples were analyzed on board following the protocols in Gieskes et al. (1991), Murray et al. (2000), and the IODP user manuals for shipboard instrumentation. Precision and accuracy were tested using International Association for the Physical Sciences of the Oceans (IAPSO) standard seawater with the following composition: alkalinity (2.353 mM), Ca (10.54 mM), Mg (54.1 mM), K (10.46 mM), Sr (93.0 µM), sulfate (28.94 mM), Cl (559.6 mM), Na (480.7 mM), and Li (26.4 µM) (Leeman Prodigy ICP-AES: User Guide).

The IW extracted from the compressed sediment sample was split into aliquots for the following analyses: (1) ~50 µL for salinity measurement with a refractometer, (2) 3 mL for pH and alkalinity, (3) 2 mL for the analysis of major, minor, and trace elements by inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES), 100 µL for ion chromatographic (IC) analysis of major anions and cations, (4) 500 µL for chloride titration, (5) 10–15 mL for oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) measurement, (6) 100 µL for ammonium analysis, and (7) 300 µL for phosphate analysis by spectrophotometry.

Salinity, alkalinity, and pH

Salinity, alkalinity, and pH were measured immediately after IW extraction, following the procedures in Gieskes et al. (1991). Salinity was measured using a Fisher temperature-compensated handheld refractometer (Fisher Model S66366). A transfer pipette was used to transfer two drops of IW to the salinity refractometer, and the corresponding salinity was recorded in the log book.

The pH was measured with a combination glass electrode, and alkalinity was determined by Gran titration with an autotitrator (Metrohm 794 basic Titrino) using 0.1 M HCl at 20°C. Certified Reference Material 104 was used for calibration of the acid. IAPSO standard seawater was used for calibration and was analyzed at the beginning and end of the sample set for each site and after every 10 samples. Repeated measurements of IAPSO standard seawater alkalinity yielded a precision <0.8%.

Oxidation-reduction potential

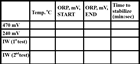

ORP was measured immediately after IW extraction from sediment in order to avoid oxidation of the IW by air. The ORP meter used during Expedition 351 comprised a glass electrode with a platinum pointer filled with an electrolyte of 3.5 M KCl + AgCl. The HANNA Instruments reference for this electrode is HI3131B, and it is coupled to the pH/ORP meter (reference HI9025). A temperature probe with a metallic pointer was coupled to the pH/ORP meter. The ORP electrode operates from –100° to +100°C, and the output ranges from –399.9 to +399.9 mV. Both ORP and temperature readings were recorded.

Standard solutions of 470 mV (reference HI7022) and 240 mV (reference HI7021) were measured before each IW sample analysis (Figure F20). If the ORP reading was more than 20 mV above the high standard value, the electrode was inserted into the reducing pretreatment solution (reference HI7091) for approximately 1 min, followed by rinsing with deionized water. Similarly, if the ORP reading was more than 20 mV below the low standard value, the electrode was inserted into the oxidizing pretreatment solution (reference HI7092) for 1 min, followed by rinsing with deionized water. When not in use, the ORP electrode was kept in a storage solution (reference HI703000).

Each IW sample was measured twice for ORP. Between measurements, the ORP and temperature electrodes were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water and dried carefully with clean, soft paper. As ORP is the measured oxidation-reduction potential in millivolts referred to the platinum electrode with an electrolyte of 3.5 M KCl + AgCl, it was converted to Eh values referred to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE), using the following equation (Nordstorm and Wilde, 2005):

where EhSHE is the redox potential (mV) referred to the standard hydrogen electrode and Ehref is the reference electrode potential (mV) corrected for the sample temperature. Whenever the sample temperature was between the listed values, a linear interpolation between two consecutive values of Table T5 was applied to calculate the corresponding Ehref value.

Table T5. Reference redox potentials for a platinum electrode with the electrolyte 3.5 M KCl + AgCl, as a function of temperature. Download table in .csv format.

Chloride

Chloride concentrations in IW samples were measured through titration using a Metrohm 785 DMP autotitrator and silver nitrate (AgNO3) solutions calibrated against repeated titrations of an IAPSO standard. Where fluid recovery was ample, a 0.5 mL sample aliquot was diluted with 30 mL of nitric acid (HNO3) solution (92 ± 2 mM) and titrated with 0.1015 M AgNO3. In all other cases, a 0.1 mL aliquot was diluted with 10 mL of 90 ± 2 mM HNO3 and titrated with 0.1778 M AgNO3. IAPSO standard solutions analyzed interspersed with the unknowns yielded a precision <0.5%.

Ion chromatography: chloride, sulfate, bromide, sodium, magnesium, potassium, and calcium

Major ions in IW samples were analyzed on a Metrohm 850 Professional II ion chromatograph equipped with a Metrohm 858 Professional sample processor, an MSM CO2 suppressor, and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). For anion (Cl, SO42–, and Br) analyses, a Metrosep C6 column (100 mm length × 4 mm inner diameter) was used, and 3.2 mM Na2CO3 and 1.0 mM NaHCO3 solutions were used as the eluent. For cation (Na, Mg, K, and Ca) analyses, a Metrosep A supp 7 column (150 mm length × 4 mm inner diameter) was used, and 1.7 mM HNO3 and 1.7 mM PDCA (pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid, CAS# 499-83-2) solutions were used as the eluent.

The calibration curve was established by diluting the IAPSO standard by 100×, 150×, 200×, 350×, and 500×. An aliquot of 100 µL IW sample was diluted 1:100 with deionized water. For every 10 samples, an IAPSO standard with specific dilution was run as unknown to ensure accuracy. Repeated measurement of anion and cation concentrations in IAPSO standard seawater yielded the following precision for each ion: Cl < 0.5%, SO42– < 0.48%, Br < 2.94%, Na < 0.36%, Mg < 0.61%, K < 14.57%, and Ca < 4.62%. The poor precision of K was due to a software integration problem, and K data obtained from ion chromatographic measurements were discarded.

Ammonium and phosphate

Concentrations of ammonium and phosphate in IW were determined on an Agilent Technologies Cary Series 100 UV-Vis spectrophotometer equipped with a sipper sample introduction system, following the protocol in Gieskes et al. (1991). The determination of ammonium in 100 μL of IW was based on diazotization of phenol and subsequent oxidation of the diazo compound by Clorox to yield a blue color, measured spectrophotometrically at 640 nm.

The determination of phosphate concentration was based on the reaction of orthophosphate with Mo(VI) and Sb(III) in an acidic solution that forms an antimony-phosphomolybdate complex, which is subsequently reduced by ascorbic acid to form a blue color. The absorbance is measured spectrophotometrically at 885 nm (Gieskes et al., 1991). For phosphate analysis, 300 µL of IW was diluted prior to color development so that the highest concentration was <1000 µM.

ICP-AES: major and minor elements

A 2 mL aliquot of IW from each sample was acidified immediately with two drops of ultrapure HNO3 after sampling and analyzed on a Teledyne Leeman Labs Prodigy high-dispersion ICP-AES for major and minor elements. The general method for shipboard ICP-AES analysis is described in ODP Technical Note 29 (Murray et al., 2000) and the user manuals for shipboard instrumentation, with modifications as indicated.

Blanks and standard solutions of known concentrations were added to each analytical run. The raw-intensity values were corrected for instrument drift and blank values. Drift correction was applied to each element by linear interpolation between the drift-monitoring solutions, except sodium, for which a second-order regression was used to accurately account for instrument response. Whenever possible, multiple wavelength analyses of an element were performed, and wavelengths generating the least scatter and smallest deviations from the certified standard values were selected. The wavelengths performed for each major and minor element in the IW samples and the wavelength selected for reporting the analytical data of each element are shown in Table T6. Major and minor elements were run in triplicate for both unknowns and standards.

Table T6. List of wavelengths performed for major and minor element analysis of the IW samples by ICP-AES. Download table in .csv format.

IW samples and IAPSO seawater standards were diluted 1:100 in a matrix solution with 2% HNO3 spiked with 10 ppm Y for major element analyses (Na, K, Mg, and Ca). For minor element analyses (Li, B, Al, Mn, Fe, Sr, Ba, and Si) IAPSO seawater standards were diluted 1:20 using the same matrix solution. Major element standards were produced by diluting IAPSO standard seawater to 120%, 100%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 10%, 5%, and 2.5% relative to the 1:100 primary dilution ratio (for more details, see Harris et al., 2013). Each IAPSO seawater dilution was run four times as unknowns throughout each analytical batch to determine the precision and accuracy. The precisions for major elements were Ca < 0.7%, K < 1.1%, Mg < 0.7%, and Na < 0.8%, and the relative deviations were Ca ± 1.0%, K ± 0.1%, Mg ± 0.6%, and Na ± 1.5%.

For minor element analysis, a stock solution was prepared by diluting ultrapure primary standards (SPC Science PlasmaCAL) of the selected minor elements (Li, B, Al, Mn, Fe, Sr, Ba, and Si) in acidified synthetic seawater from which serial dilutions of 100%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 10%, 5%, 2.5%, and 1% were prepared. IAPSO standards were analyzed as unknowns interspersed with IW samples in a batch to ensure the precision and accuracy. Calibration standards were analyzed in triplicate and yielded an average precision of B < 2.1%, Ba < 1.8%, Li < 8.2%, Si < 2.5%, Mn < 0.8%, and Sr < 1.3%. Relative deviations were B ± 2.9%, Ba ± 16.1%, Li ± 0.4%, Si ± 0.6%, Mn ± 0.7%, and Sr ± 2.0%.

The calibration standards analyzed in triplicate for Fe and Al yielded a precision of Fe < 1.3% and Al < 2.2%, whereas the accuracy was Fe < 1.0% and Al < 1.2%. The detection limits for Fe and Al were 2.08 and 0.38 µM, respectively. Given the fact that all the IW samples analyzed were below the detection limit for both Fe and Al, data for these elements are not reported.

When preparing the IW for a second set of analyses, white and translucent crystals were observed in 15 of the 67 IW samples acidified after sampling. These crystals were photographed and identified by smear slide and X-ray diffraction (for more details, see Geochemistry in the Site U1438 chapter [Arculus et al., 2015]). However, no crystals formed in the untreated ion chromatography splits for these samples. The splits were acidified and prepared for ICP-AES as described above.

Sediment bulk geochemistry

An aliquot of the “squeeze cake” produced when compressing the sediments for IW extraction was freeze-dried for ~24 h to remove water and then ground to powder to ensure homogenization. This aliquot was used for sediment bulk geochemical analyses.

Carbonate content

Inorganic carbon content was determined by acidifying approximately 11 mg of the bulk powder with 5 mL of 2 M HCl at 40°C and measuring the amount of CO2 generated on a UIC 5015 CO2 coulometer. Its volume was determined by trapping the CO2 with ethanolamine and titrating coulometrically with the hydroxy-ethylcarbamic acid. The end-point of the titration was determined by a photodetector, where the change in light transmittance is proportional to the inorganic carbon (IC) content of the sample. The weight percent of carbonate was calculated from total inorganic carbon by:

CaCO3 (wt%) = IC (wt%) × 8.33.

All CO2 was assumed to derive from dissolution of CaCO3. No corrections were made for other carbonate minerals.

Total carbon, total organic carbon, and total nitrogen

Approximately 10 mg of bulk powder was weighed into a tin capsule to determine the total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) content. The powder was combusted in an oxygen gas stream at 900°C on a Flash EA-1112 Series Thermo Electron Corporation carbon-hydrogen-nitrogen-sulfur (CHNS) analyzer equipped with a Thermo Electron packed column CHNS/NCS and a TCD for TC and TN. Reaction gases were passed through a reduction chamber to reduce nitrogen oxides to N2, and the mixture of CO2 and N2 was separated by gas chromatography and detected by the TCD. Calibration was based on the Thermo Fisher Scientific NC Soil Reference Material standard that contains 2.29 wt% C and 0.21 wt% N. This standard was chosen because the elemental C and N compositions in the standard are close to those expected at Site U1438. Total organic carbon was calculated by subtracting weight percent of inorganic carbon from TC obtained with the CHNS analyzer.

Sampling and analysis of igneous and volcaniclastic rocks with ICP-AES

The ICP-AES protocols for sample digestion and analysis used during Expedition 351 are outlined in Murray et al. (2000). Representative samples of igneous, volcaniclastic rocks and volcaniclastic sediments were selected in collaboration with shipboard igneous petrologists/core describers and analyzed for major and trace element contents using ICP-AES.

Sample preparation

Igneous rocks (~2–8 cm3) were cut from the core with a diamond saw blade. A thin section billet was taken from the same or adjacent interval. To remove altered rinds and surface contamination, all cutting surfaces were ground on a diamond-impregnated disk. Igneous rock blocks were placed in a beaker containing trace-metal-grade methanol and washed in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min. The methanol was decanted, and the samples were washed in deionized water for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were placed in an ultrasonic bath of Barnstead deionized water (~18 MΩ·cm) for 10 min. The cleaned pieces were dried for 10–12 h at 110°C.

After drying, the igneous samples were crushed to <1 cm between two Delrin plastic disks in a hydraulic press. The chips were ground to a fine powder in a SPEX 8515 Shatterbox with a tungsten carbide lining. An aliquot of sample powder was weighed to 1000.0 ± 0.5 mg and then ignited at 700°C for 4 h to determine weight loss on ignition.

Volcaniclastic sediments and ash layers were sampled by scooping, whereas lapilli-sized pumice clasts were hand-picked, targeting a total sample volume of ~5 cm3. Volcaniclastic sediments and ashes were freeze-dried (10–12 h). The samples were ground to a fine powder in the SPEX 8515 Shatterbox, and an aliquot of sample powder weighing 1000.0 ± 0.5 mg was ignited at 700°C for 4 h to determine loss on ignition.

Each sample and standard was weighed on a Cahn C-31 microbalance to make 100.0 ± 0.2 mg splits; weighing errors were estimated to be ±0.05 mg under relatively smooth sea-surface conditions. Splits of ignited whole-rock powders were mixed with 400.0 ± 0.5 mg of LiBO2 flux (preweighed on shore). During each ICP-AES analysis, standard rock powders and full procedural blanks were interspersed with unknowns (among the elements reported, contamination from the tungsten carbide mills is negligible) (Shipboard Scientific Party, 2003).

Aqueous LiBr solution (10 mL of 0.172 mM) was added to the flux and rock powder mixture as a nonwetting agent prior to sample fusion to prevent the fused bead sticking to the crucible during cooling. Samples were fused individually in Pt-Au (95:5) crucibles for ~12 min at a maximum temperature of 1050°C in an internally rotating induction furnace (Bead Sampler NT-2100).

The beads were transferred into 125 mL high-density polypropylene (HDPE) bottles and dissolved in a 50 mL solution containing 10% HNO3 and 10 ppm Ge. The solution bottle was placed in a Burrell wrist-action shaker for 1 h to aid dissolution. Next, 20 mL increments of the solution were passed through a 0.45 µm filter into a clean 60 mL wide-mouth HDPE bottle. From the filtered solution, 1.25 mL was pipetted into a scintillation vial and diluted with 8.75 mL of dissolution solution containing 10% HNO3. The final solution-to-sample dilution factor was 4000; this solution was used to analyze both major and trace elements. For standards, stock standard solutions were placed in an ultrasonic bath for 1 h prior to final dilution to ensure a homogeneous solution.

Analysis and data reduction

Major (Si, Ti, Al, Fe, Mn, Mg, Ca, Na, K, and P) and trace (Sc, V, Cr, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Rb, Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Ba, Ce, and Nd) element concentrations of samples and standards were measured on a Teledyne Leeman Labs Prodigy ICP-AES instrument.

Whenever possible, multiple wavelength analyses of an element were performed (e.g., Si at 250.690 and 251.611 nm), and the wavelength with the least scatter and smallest deviations from the certified standard concentration was selected (Table T7).

Table T7. Wavelengths performed for major and trace element analysis of rock samples by ICP-AES. Download table in .csv format.

To allow the instrument to stabilize, the plasma was ignited at least 30 min before each ICP-AES run. A zero-order search was performed to check the mechanical zero of the diffraction grating, and then the mechanical step positions of emission lines were tuned by automatically searching with a 0.002 nm window across each emission peak using single-element solutions. No alignment solutions were available for Ce and Nd; therefore, each wavelength corresponding to the element was scanned manually while analyzing a standard, and the closest reproducible value was chosen. The ICP-AES data were acquired using the Gaussian mode of the instrument software. Each sample was analyzed in quadruplicate within a given sample run. Between analyses, a 10% HNO3 solution was introduced for 90 s. Blank solutions aspired during each run were below the detection limit.

A typical ICP-AES run included a subset from 13 certified rock standards (AGV, BCR-2, BHVO-2, GSP-2, JB-2, JG-2, JG-3, JP-1, JR-1, JR-2, Nod-A-1, STM-1, and VS-N) interspersed with the samples in quadruplicate. The criteria for standard selection were to best cover the range of chemical compositions and matrixes for Expedition 351 samples. Standard JB-2 is from the Izu-Bonin arc, so it was analyzed as an unknown because its composition could potentially match the Expedition 351 samples (Table T8).

Table T8. JB-2 check standard data for ICP-AES analysis. Download table in .csv format.

For drift correction, a solution containing Standard JR-2 was analyzed at the beginning and end of each run and interspersed in the sequence. Measured raw intensities were corrected offline for instrument drift using the shipboard ICP Analyzer software. A linear calibration line for each element was calculated using the results for the certified rock standards. Element concentrations in the samples were then calculated from the relevant calibration lines. Data were rejected if volatile-free major element weight percentages were outside 100 ± 5 wt%. Sources of error included weighing (particularly in rougher seas), sample and standard dilution, and instrumental instabilities. Major element data were reported normalized to 100 wt% total. Total iron was stated as Fe2O3t.

Major element standards were analyzed as unknowns in the batch of sediment and rock samples to check the precision of the method. Calibration standards were analyzed in quadruplicate and yielded a precision of Al < 0.4%, Ca < 0.6%, Fe < 0.5%, K < 0.6%, Mg < 0.5%, Mn < 0.6%, Na < 1.5%, Si < 0.4%, Ti < 0.5%, Ba < 1.5%, Cr < 6.6%, Sr < 0.9%, Sc < 1.6%, V < 9.7%, Y < 1.0%, and Zr < 1.7%.

Processing samples for onshore analysis

Interstitial water splits for onshore analysis

From the volume of IW remaining after shipboard analysis splits, additional splits were made for onshore analyses. These included

- 2 mL for onshore metal trace element analysis,

- 1 mL for oxygen isotopes (18O/16O) of water,

- 1 mL for hydrogen isotopes (2H/1H) of water, and

- 3 mL for carbon isotopes (13C/12C) of dissolved inorganic carbon.

In addition, the IW residue generated after titration with HCl for alkalinity determination and the residue generated from the ORP measurements (which is a nondestructive method) were subsequently processed for onshore analysis of 34S/32S isotopes from dissolved sulfate and sulfide.

Processing IW samples for onshore stable isotope analyses

IW samples were processed onboard for postexpedition stable isotope analyses. Following the methods proposed in Clark and Fritz (1997) for the determination of 13C/12C in dissolved inorganic carbon, 3 mL of IW was stored in a glass vial covered with opaque tape (to keep the IW sample dark) and spiked with a minor amount of Na-azide (NaN2, less than the tip of a spatula) to prevent biological activity inside the vial. For the determination of 34S/32S in dissolved sulfate and sulfide, the residue from ORP measurements was used, and whenever the recovery of IW volume was too low, the residue from alkalinity measurements was used. In order to fix aqueous sulfide, IW left from ORP measurements was spiked with zinc acetate (1–2 g) to precipitate ZnS. This precipitate was filtered through a 0.45 µm filter, dried, and stored in a polypropylene bottle. In order to fix aqueous sulfate, the filtered solution was acidified by adding 1 M HCl until a pH of 4–5 was reached, and then BaCl2·2H2O was added to prevent BaCO3 precipitation. The BaSO4 precipitate was allowed to settle for 4 h, after which it was decanted and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter. After drying, the BaSO4 precipitate was stored in a polypropylene bottle.

Sediment and IW sampling for postexpedition dissolved trace metal analysis

For the onshore analyses of dissolved trace metals (e.g., Mo, Co, Re, and U), two 10 mL syringe samples per core were taken from undisturbed sediments at the bottom of Sections 1 and 5 of each core immediately upon retrieval. When later core splitting revealed that the sediments at these depths were disturbed, they were replaced by 10 cm3 scoop samples from the split core. To minimize oxidation, wet samples were frozen and freeze-dried on board.

A 2 mL aliquot of IW was acidified by adding 10 µL of concentrated HNO3 and stored at room temperature. A quarter of the sediment residue after IW extraction was freeze-dried for later postexpedition trace metal analysis.

Processing of sediments for onshore microbiological analyses

For onshore microbiological analyses of sediments and rocks collected during Expedition 351, approximately 30 cm3 of sediment was collected with a minicorer (sterilized syringe with its pointer cut off), normally from the lower part of Section 3, immediately above the whole round that was taken for IW (Figure F19). A total of 21 samples were collected in Hole U1438B, three samples in Hole U1438D, and three samples in Hole U1438E.

Immediately after sampling on the catwalk, the samples were taken to the Geochemistry laboratory and were split into two subsamples: 20 cm3 for pyrosequencing of DNA and 10 cm3 for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

From the subsample taken for pyrosequencing, approximately 0.5 g of sediment was stored in a sterilized Eppendorf tube filled with glycerol at 40%. The remaining amount of sediment collected for pyrosequencing was stored in a sterilized Falcon tube. The two subsamples for pyrosequencing were stored and shipped frozen at −80°C.

The 10 cm3 of sediment and/or rock collected for FISH was fixed shipboard using three solutions:

- D17 water, filtered with a membrane filter with pore size of 0.22 µm and sterilized (i.e., autoclaved) with formaldehyde, at a final concentration of 2%;

- 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution (CAS 7647-14-5); and

- 1× PBS with 80% ethanol at a ratio of 1:1.

Fixation of the sediment samples for FISH was done by splitting each sample into 10 subsamples of 1.0 g, each weighed in a 4 mL Eppendorf tube, and then following the steps below:

- 3.0 mL of D17 water with formaldehyde was added to each Eppendorf tube.

- The sediment with D17 water with formaldehyde was stored for 4 h, shaking the samples every hour (manually or with the aid of a shaker).

- After completing the 4 h period of fixation, the Eppendorf tubes were centrifuged for 2 min at a relatively high rotation rate (2600 rpm). The objective of this step was to separate the aqueous solution from the solid particles. In this context, after centrifuging the Eppendorf tubes, the aqueous solution was discarded, leaving only the solid phase at the bottom.

- 3.0 mL of the solution 1× PBS was added to each Eppendorf tube. In order to suspend the sediment and mix it well with the 1× PBS solution, each Eppendorf tube was shaken in the shaker.

- The Eppendorf tubes were then centrifuged again for 2 min (2600 rpm) in order to separate the solution from the sediment. After centrifugation, the aqueous solution was discarded, leaving only the solid phase at the bottom.

- Steps 4 and 5 were repeated.

- After repeating Steps 4 and 5, the aqueous solution (i.e., supernatant) was discarded and 3.0 mL of the solution 1× PBS with 80% ethanol at 1:1 was added to each Eppendorf tube.

- The mixture of the sediment with the solution 1× PBS with ethanol (80%) at 1:1 was suspended in the shaker, and the Eppendorf tubes were stored at –80°C.

Paleomagnetism

During Expedition 351, routine shipboard paleomagnetic and magnetic anisotropy experiments were carried out. Remanent magnetization was measured on archive section halves and on discrete cube samples taken from the working halves. Continuous archive section halves were demagnetized in an alternating field (AF), whereas discrete samples were subjected to stepwise AF demagnetization or low-temperature demagnetization followed by thermal treatment. Because the azimuthal orientations of core samples recovered by rotary drilling are not constrained, all magnetic data are reported relative to the sample core coordinate system (Fig. F3). In this system, +x points into the working section half (i.e., toward the double line), +z is downcore, and +y is orthogonal to x and z in a right-hand sense.

Archive section-half remanent magnetization data

Measurement

The remanent magnetization of archive section halves was measured at 2 cm intervals using the automated pass-through direct-current superconducting quantum interference device (DC-SQUID) cryogenic rock magnetometer (2G Enterprises model 760R). An integrated inline AF demagnetizer (2G model 600) capable of applying peak fields up to 80 mT was used to progressively demagnetize the core. Variable demagnetization step intervals from 2 to 40 mT were adopted, based on the type of material being analyzed: steps of 25, 35, and 40 mT were used on sediment sections (after pilot experiments demonstrated that only a drilling-induced remanence was present up to 25 mT), but more detailed experiments using 2 and 5 mT steps were performed on basement samples (made possible by the slow rate of hard rock core recovery). Demagnetization in AFs > 40 mT was not attempted because of a well-documented problem with the SRM demagnetization coils that has been a characteristic of the SRM system observed on several Integrated Ocean Drilling Program expeditions (e.g., see Expedition 335 Scientists, 2012), which results in acquisition of spurious, laboratory-imparted anhysteretic remanent magnetizations (ARMs) along the z-axis of the SRM system at higher applied fields (and which was found to still persist during Expedition 351).

For sedimentary sections, a magnetometer track velocity of 10 cm/s was used to optimize the rate at which core could be processed. With more strongly magnetized materials, the maximum intensity that can be reliably measured (i.e., with no residual flux counts) is limited by the slew rate of the sensors. At a track velocity of 2 cm/s, it is possible to measure archive section halves with a magnetization as high as ~10 A/m (Expedition 304/305 Scientists, 2006; Expedition 330 Scientists, 2012), and so the track velocity was reduced to 2 cm/s in the more intensely magnetized igneous basement rocks.

The compiled version of the LabView software (SRM section) used during Expedition 351 was SRM version 318. In this version (Expedition 330 Scientists, 2012), the speed at which the archive section is moved when not measuring is set at 20 cm/s, and simultaneous sampling of the magnetometer axes is incorporated.