Lucchi, R.G., St. John, K.E.K., Ronge, T.A., and the Expedition 403 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 403

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.403.104.2026

Site U16191

![]() K.E.K. St. John,

K.E.K. St. John,

![]() R.G. Lucchi,

R.G. Lucchi,

![]() T.A. Ronge,

T.A. Ronge,

![]() M.A. Barcena,

M.A. Barcena,

![]() S. De Schepper,

S. De Schepper,

![]() L.C. Duxbury,

L.C. Duxbury,

![]() A.C. Gebhardt,

A.C. Gebhardt,

![]() A. Gonzalez-Lanchas,

A. Gonzalez-Lanchas,

![]() G. Goss,

G. Goss,

![]() N.M. Greco,

N.M. Greco,

![]() J. Gruetzner,

J. Gruetzner,

![]() L. Haygood,

L. Haygood,

![]() K. Husum,

K. Husum,

![]() M. Iizuka,

M. Iizuka,

![]() A.K.I.U. Kapuge,

A.K.I.U. Kapuge,

![]() A.R. Lam,

A.R. Lam,

![]() O. Libman-Roshal,

O. Libman-Roshal,

![]() Y. Liu,

Y. Liu,

![]() L.R. Monito,

L.R. Monito,

![]() B.T. Reilly,

B.T. Reilly,

![]() Y. Rosenthal,

Y. Rosenthal,

![]() Y. Sakai,

Y. Sakai,

![]() A.V. Sijinkumar,

A.V. Sijinkumar,

![]() Y. Suganuma, and

Y. Suganuma, and ![]() Y. Zhong2

Y. Zhong2

1 St. John, K.E.K., Lucchi, R.G., Ronge, T.A., Barcena, M.A., De Schepper, S., Duxbury, L.C., Gebhardt, A.C., Gonzalez-Lanchas, A., Goss, G., Greco, N.M., Gruetzner, J., Haygood, L., Husum, K., Iizuka, M., Kapuge, A.K.I.U., Lam, A.R., Libman-Roshal, O., Liu, Y., Monito, L.R., Reilly, B.T., Rosenthal, Y., Sakai, Y., Sijinkumar, A.V., Suganuma, Y., and Zhong, Y., 2026. Site U1619. In Lucchi, R.G., St. John, K.E.K., Ronge, T.A., and the Expedition 403 Scientists, Eastern Fram Strait Paleo-Archive. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 403: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.403.104.2026

2 Expedition 403 Scientists' affiliations.

1. Background and objectives

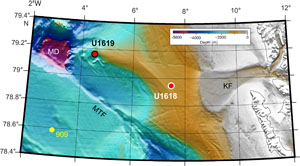

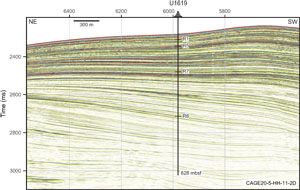

The Vestnesa Ridge is a roughly east–west-oriented prominent bathymetric feature situated in the Fram Strait on the western continental margin of Svalbard (Figure F1). Its evolution is linked to the tectonic, sedimentary, and climatic history of the region, making it a focal point for multidisciplinary scientific research. The 100 km long ridge is a sediment drift generated by persistent bottom currents associated with the West Spitsbergen Current (WSC) (Eiken and Hinz, 1993) that developed over oceanic crust since the Fram Strait opening (17–10 Ma; Jakobsson et al., 2007; Engen et al., 2008; Ehlers and Jokat, 2013). Although the chronology of the Vestnesa Ridge sediment record deposited since the last glacial is well established and regionally correlatable (Lucchi et al., 2023), the chronology prior to approximately Marine Isotope Stages (MISs) 3 and 4 is limited to extrapolation made from seismic data from previously drilled sites on the Yermak Plateau (Ocean Drilling Program [ODP] Site 912) and south of the Molloy Transform Fault (ODP Site 909) (Eiken and Hinz, 1993; Knies et al., 2014; Mattingsdal et al., 2014). Seismic Reflectors R1–R8 were drilling targets for Site U1619 (Figure F2), with a total depth target of 696 meters below seafloor (mbsf).

The sedimentation and geologic development in this area has been heavily influenced by the Pliocene–Pleistocene glaciations, especially the ice sheet extent over Svalbard and the Barents Sea, and the Arctic Ocean sea ice extent (Jakobsson et al., 2014). Depositional facies representing a range of glaciogenic and bottom current depositional processes are well documented in the recent sedimentary record along the western Svalbard continental margin (e.g., Lucchi et al., 2013, 2015; Caricchi et al., 2019) and the Vestnesa Ridge (Schneider et al., 2018; Sztybor and Rasmussen, 2017; Plaza-Faverola et al., 2023; Rasmussen and Nielsen, 2024). The presence of gas hydrates and associated fluid migration are additional controls on the sedimentary record of the Vestnesa Ridge, although they affect the central and eastern areas of the ridge more than the western termination (see Background and objectives in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b]).

The West Vestnesa Ridge is characterized by a larger crest (>10 km wide) than in the eastern termination (~3 km) and contains small, apparently inactive pockmarks, although multidisciplinary investigations point to the presence of methane in the subseafloor (e.g., Hustoft et al., 2009; Bünz et al., 2012; Consolaro et al., 2015; Plaza-Faverola et al., 2015; Sultan et al., 2020).

Site U1619, located on the Vestnesa Ridge West termination, was chosen as the northernmost site in Expedition 403. The site is well situated to provide a record of both high-resolution variability and long-term changes in the northward penetration of North Atlantic waters transported by the WSC at the gateway to the Arctic. The more distal setting of Site U1619, compared to Site U1618, also provides the opportunity to laterally trace glaciogenic deposits originating from the paleo-Svalbard–Barents Sea Ice Sheet (SBSIS) and to examine the history of Arctic sea ice extent into the Fram Strait. For these reasons, sediment drift Site U1619 is ideal for paleoceanographic and paleoclimatic studies that can complement research from prior scientific ocean drilling sites farther north (e.g., ODP Sites 910 and 912 on the Yermak Plateau) and south (e.g., ODP Site 908 on the Hovgaard Ridge and ODP Site 909 in the Molloy Basin) (Myhre et al., 1995).

Because of unfavorable sea ice conditions, Site U1619 comprises only a single hole (U1619A) drilled at a 1676 m water depth and reaching a subseafloor penetration of 628 mbsf. Hole U1619A is positioned at the cross point of two seismic lines: CAGE20-5-HH-11-2D and CAGE20-5-HH-10-2D (Figure F1). No gas hydrate–related bottom-simulating reflector was detected close to Hole U1619A.

The research objectives for this site include the following:

- Definition of a high-resolution sediment stratigraphy since the Late Miocene–Early Pliocene transition;

- Reconstruction of the variability of the WSC transporting warm Atlantic Water to the Arctic;

- Definition of the effect of glacial and tectonic stresses on subseafloor sediment deformation and carbon transport; and

- Investigation of the influence of the WSC variability, ice coverage, and climate on the microbial populations through time and to what extent this is still affecting contemporary geochemical fluxes.

2. Operations

A total of 5.27 days were spent at Site U1619, penetrating to a maximum depth of 627.9 mbsf. This cored interval of 627.9 m resulted in a recovered length of 728.35 m. Site U1619 consists of only one hole on Seismic Line CAGE20-5-HH-10-2D. We took 85 cores in total: 13% with the advanced piston corer (APC) system (11 cores), 13% with the half-length APC (HLAPC) system (11 cores), and 74% with the extended core barrel (XCB) system (63 cores). To minimize magnetic overprinting on the cored sediment, nonmagnetic collars and core barrels were used for all APC and HLAPC coring. Hole U1619A had intervals where the sediments significantly expanded due to the presence of gas, resulting in recoveries often exceeding 100% (Table T1). To mitigate the impact of expansion and the potential for core disturbance and to release the pressure, holes were drilled into the liner by the drill crew on the rig floor and the technical staff on the core receiving platform. In addition, most XCB cores were advanced by 6–8 m to allow for gas expansion. Hole U1619A was terminated at 627.9 mbsf before sea ice began to move into the area. A free-fall funnel (FFF) was deployed in hopes that the ship could reoccupy the hole, but it appeared that the ice would be in the area for at least 10 days, so the hole and site were abandoned. Ultimately, the ice conditions throughout Expedition 403 remained unfavorable, preventing a return to the site.

To more easily communicate shipboard results, core depth below seafloor, Method A (CSF-A), depths in this chapter are reported as mbsf unless otherwise noted.

2.1. Hole U1619A

The vessel made the 36.3 nmi transit to Site U1619 in 3.2 h with an average speed of 11.3 kt. The thrusters were down and secure, and the vessel switched from cruise mode to dynamic positioning (DP) control at 1545 h on 23 June 2024, starting Site U1619 and Hole U1619A. A beacon was deployed, and a depth reading with the precision depth recorder (PDR) was taken as the vessel arrived. The PDR indicated that the seafloor was 1675.4 meters below sea level (mbsl). The crew assembled and deployed an APC/XCB bottom hole assembly. Hole U1619A was spudded at 2210 h (UTC + 2 h) on 23 June. The seafloor was estimated to be 1676.1 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. APC coring continued to 87.4 mbsf. Partial strokes on Cores 10H and 11H determined APC refusal, and the HLAPC system was deployed to advance the hole to 150.1 mbsf (Cores 12F–22F). Partial strokes on Cores 21F and 22F determined HLAPC refusal. The XCB coring system was deployed to advance the hole from 150.1 mbsf to the total depth of 627.9 mbsf on 28 June (Cores 23X–85X). Because expanding cores were an issue when using the APC and HLAPC tools, advances using the XCB system were kept to approximately 7.0 m to allow room in the liner for the core to expand.

On the morning of 28 June, the ice navigators notified the bridge that the marginal sea ice zone had moved to within 3 nmi of the vessel. It was decided to deploy a FFF in case the vessel was forced off location. While deploying the FFF, ice moved into the red zone (closer than 3 nmi) from both the northwest and southwest. Thus, it was decided to terminate coring and end operations until the site cleared. The drill string was pulled to the surface, clearing the seafloor at 1505 h on 28 June. The beacon was released after clearing the seafloor and was recovered at 1600 h. The bit cleared the rig floor at 1940 h, and the rig floor was secure for transit at 1952 h. The vessel was switched from DP to cruise mode at 1955 h on 28 June, ending Hole U1619A and Site U1619.

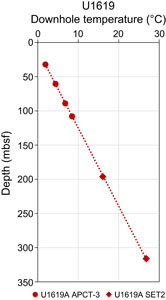

A total of 85 cores were taken over a 627.9 m interval. The APC system was deployed for 11 cores over 98.4 m with 102.33 m of recovery (104%); the HLAPC system was used for 11 cores over a 51.7 interval, recovering 54.13 m of sediment (105%); and the XCB system was deployed for 63 cores over 477.8 m, recovering 571.89 m of sediment (120%). Formation temperature measurements were taken with the advanced piston corer temperature (APCT-3) tool on Cores 4H, 7H, 10H, and 13F and the Sediment Temperature 2 (SET2) tool after Cores 28X (197.0 mbsf) and 44X (317.0 mbsf). A total of 124.50 h (5.2 days) were spent on Hole U1619A.

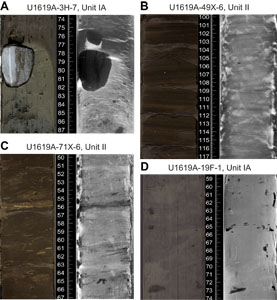

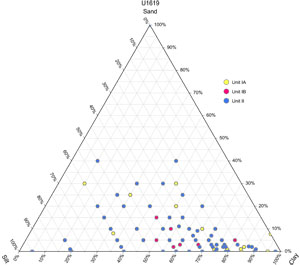

3. Lithostratigraphy

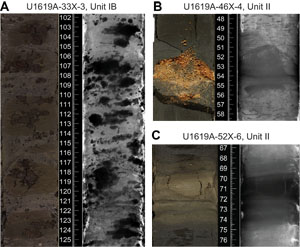

Site U1619 comprises a single hole, and the lithostratigraphy of Site U1619 is based on observations and measurements of 85 cores from Hole U1619A. This cored sequence spans 627.9 m of cored length and, because of gas expansion, 728.35 m of recovered length. The sediments exhibit increasing lithification with depth, with a gradational transition from soft to firm beginning at 68.61 mbsf and a transition to hard sediments at 594.60 mbsf. The sediments are primarily siliciclastic, mainly composed of silty clay, clayey silt, clay, and sandy mud, with fewer intervals of clayey sand, sandy clay, sandy silt, silt, and silty sand. Additionally, there is one interval of calcareous-rich (10%–30%) sediments in Core 403-U1619A-3H, a few intervals of biosiliceous-rich sediments in Sections 19F-1 and 19F-4, and biosiliceous-bearing (5%–10%) sediments in Sections 22F-1 and 22F-3 and all sections of Core 34X. These lithologies vary in color, with biogenic-bearing to biogenic-rich sediments appearing dark greenish-gray (5GY 4/1 and 10GY 4/1; Figure F3A), whereas siliciclastic sediments are most commonly gray (5Y 5/1 and N 5/), dark gray (5Y 4/1, N 4/, 10YR 4/1, and 2.5Y 4/1), very dark gray (10YR 3/1, 2.5Y 3/1, 5Y 3/1, and N 3/), dark greenish gray (10R 3/1 and 10Y 3/1), very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2), and black (2.5Y 2.5/1, 5Y 2.5/1, and 10YR 2/1) (Figure F3B–F3D). These sediments contain varying amounts of authigenic mineral precipitants (Figure F4), detrital clasts (Figure F5A), laminations (Figure F5B), bioturbation (Figure F5C), and dark patches (Figure F5D). Small (<2 cm) to large (>2 cm) clasts are identified throughout cores from visual core description and X-radiograph observations and range in abundance from dispersed (<1%) to common (1%–5%) to abundant (5%–30%). Clast abundance did not reach >30% at Site U1619.

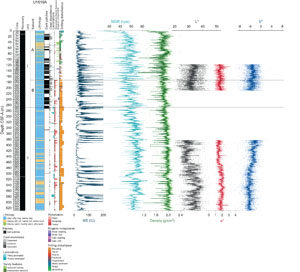

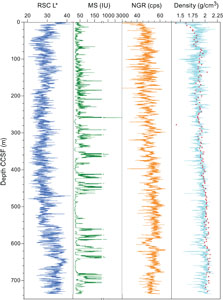

Authigenic mineral precipitants occurred in varying forms at Site U1619, including iron sulfide minerals (Figure F4A); lenses of yellowish orange sand-sized carbonate minerals in Cores 403-U1619A-45X, 46X, 48X, 54X, 57X, and 58X (Figure F4B); and light brownish gray mud layers composed primarily of authigenic carbonates (Figure F4C). Although sedimentary structures are occasionally difficult to identify on the split core surfaces (i.e., described as structureless), primary (e.g., laminations and bioturbation) and secondary (e.g., bioturbation infilled by authigenic minerals; Figure F5C) sedimentary structures are more commonly visible in the X-radiographs. Summary lithologic information for Hole U1619A is plotted alongside magnetic susceptibility (MS), natural gamma radiation (NGR), gamma ray attenuation (GRA) density, and color reflectance (L*, a*, and b*) data in Figure F6. The Section Half Multisensor Logger (SHMSL) was not contacting the sediment core surface while scanning Cores 1H–53X, and thus color reflectance and point MS (MSP) measurements are not reliable uphole of Core 54X. Sedimentologists worked to rescan Cores 16F–30X, and the presented results include these corrected measurements. However, the SHMSL data from these cores remain suspect; therefore, caution is warranted in using the color reflectance and the split core MS SHMSL data from Hole U1619A. MS measured on the Whole-Round Multisensor Logger (WRMSL) is reliable (see Physical properties).

The presence and degree of drilling disturbance varies depending on the depth and drilling technique used. Sediments in the upper ~130 m tend to be slightly to strongly soupy and uparching, with the start of slight to moderate biscuiting below ~156 mbsf. Moderate biscuiting continues in the deeper part of the drilled sequence, where it becomes progressively more severe and is the primary drilling disturbance, along with slightly to moderately fractured intervals. Biscuiting seems to affect fine-grained sediments more than coarse-grained intervals, where the presence of larger clasts seems to stabilize the sediments and prevent them from severe disturbance.

The sediments from Site U1619 exhibit some similarities to ODP Site 909 (Myhre et al., 1995), which is the nearest drilling site. Similar to Site U1619, the primary lithology of Site 909 includes gray to dark gray silty clays, clays, and muds with varying amounts of sand and/or clasts larger than 2 cm, bioturbated intervals, a variety of authigenic carbonate layers and nodules, absent to rare biogenic material, and thinly laminated intervals. Differences between Sites 909 and U1619 arise when comparing depths of large clasts (>2 cm) and the onset of well-defined laminations. Whereas at Site U1619 large clasts occur consistently (minimum every 30 m) from 0 to 260 mbsf and dispersed clasts (<2 cm) occur down to ~280 mbsf and occasionally further downhole, there are no dropstones below 240 mbsf at Site 909. Additionally, laminations occur at shallower core depths at Site U1619 than at Site 909, starting approximately at 258 mbsf at Site U1619 and from about 518 mbsf at Site 909.

Based primarily on differences in clast abundance, dark patches, and laminations, the sediment sequence at Site U1619 is divided into two main lithostratigraphic units.

3.1. Lithostratigraphic unit descriptions

3.1.1. Unit I

The sediment in Lithostratigraphic Unit I is predominantly dark gray (5Y 4/1) and dark to very dark greenish gray (10Y 4/1 to 10Y 3/1) silty clay (Figure F7) throughout with frequent intervals of gray (N 5/) to dark gray (N 4/) clayey silt within the uppermost 70 m of Hole U1619A and occasionally dark gray (5Y 4/1) interbedded silt, black (N 2.5/) sandy silt layers, and reddish gray (10Y 5/1) to dark gray (5Y 4/1) intervals of clay. Although very rare, Unit I contains a few biogenic-bearing and biogenic-rich intervals in notably light greenish-gray intervals. Based on visual observations of the split core surface and examination of X-radiographs, the presence of gravel- to pebble-sized (2–64 mm) clasts is consistent throughout Unit I, ranging from dispersed to abundant downhole. The larger clasts (>2 cm) tend to be angular to subangular when present. Bioturbated sediments are rare throughout the uppermost 174 m of Unit I but become increasingly frequent and range in severity from slight to moderate from 174 mbsf downhole. Authigenic carbonate is observed at ~160 mbsf and continues downhole, occurring throughout the lower intervals of Unit I.

Lithostratigraphic Unit I can be divided into two subunits (IA and IB) based on differences in the occurrence of bioturbation, clasts > 2 cm, silt abundance, and MS data. This subunit boundary is located at the base of Core 403-U1619A-25X at 174.76 mbsf (Table T2).

3.1.1.1. Subunit IA

Lithostratigraphic Subunit IA is the youngest in the stratigraphic sequence and is characterized by relatively soft and soupy silty clay/clayey silt (Figure F7), especially in Cores 403-U1619A-1H through 9H, and is less bioturbated overall, with no evidence of diagenesis and variable presence of dark patches. Dispersed clasts are common. Authigenic carbonate formation begins toward the base of Subunit IA and continues consistently downhole. MS data show relatively low values within Subunit IA to ~130 mbsf. NGR and density display high-amplitude variability in this subunit. The majority of this subunit has little SHMSL analytical coverage; therefore, color reflectance data were not used to determine the lithologic subunit boundary for Site U1619.

3.1.1.2. Subunit IB

Lithostratigraphic Subunit IB is characterized by firm, bioturbated silty clay/clay (Figure F7) sediments, a slight increase in overall clast abundance, a decrease in silt content, and a more consistent presence of dark patches compared to Subunit IA. Bioturbation ranges in severity from slight to moderate throughout Subunit IB and is present in all cores from Core 403-U1619A-25X to the base of the subunit. Rare authigenic iron sulfide minerals and common authigenic carbonate formation in the form of layers, sandy lenses, and laminations continue downhole. Authigenic carbonate minerals sometimes appear as slightly brownish gray on the split core surface but are more easily identified in X-radiographs as dense intervals (Figure F4D). High peaks in MS are common, and the NGR and density values show slightly lower amplitude variabilities than in Subunit IA.

3.1.2. Unit II

- Interval: 403-U1619A-38X-4, 90 cm, to the bottom of the hole

- Depth: 267.91 mbsf to the bottom of the hole

- Age: Pliocene to Late Miocene

Lithostratigraphic Unit II is composed primarily of dark to very dark greenish gray (10Y 3/1) silty clay (Figure F7) and gray (10YR 5/1) to grayish green clay and clayey silt, with occasional intervals of gray to dark greenish gray (10Y 4/1) sandy mud and intervals without sand fraction (Figure F3B, F3C). The defining feature of Unit II is the presence of thinly (<0.3 cm) to thickly (0.3–1 cm) laminated sediments beginning in Core 403-U1619A-38X and continuing downhole and rare to no dark patches. No biogenic material is observed in smear slides.

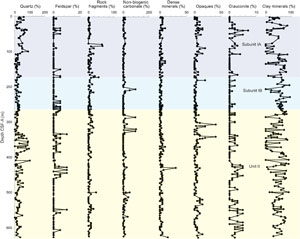

Mineralogy is variable with few differences between lithostratigraphic units. Clay minerals typically are the most abundant component in smear slides, except in samples from coarser lithologies where other mineral components increase in abundance. Quartz abundance tends to be relatively high from ~340 to 480 mbsf, and feldspar abundance is ≥2% every ~100 m throughout the record. Peaks exceeding 30% in dense and opaque mineral abundance in Lithostratigraphic Unit II occur at ~460 and 320–340 mbsf, respectively. Nonbiogenic carbonate is highest from ~300 to 335 mbsf, and glauconite shows an inconsistent pattern of high and low peaks throughout (Figure F8). Based on visual observations of the split core surface and examination of X-radiographs, the presence of gravel to pebble-sized (2–64 mm) clasts is infrequent throughout Unit II and decreases downhole. Overall clast abundance is also lower within this unit, and clasts are typically dispersed, if present. Bioturbation is frequent within Unit II, ranging in severity from slight to heavy. Both NGR and density show a stepwise decrease at the Unit I/II boundary but increase variability again with depth. A slight positive shift at ~470 mbsf in the L* and a* data and a negative shift in the b* data align with increased MS values but do not relate to a noticeable change in lithology. The very high MS values seen in Subunit IA also occur in Unit II, but they are interrupted by 10–80 m long intervals of low MS values. MS does not seem to match patterns in NGR or density within Unit II (Figure F6).

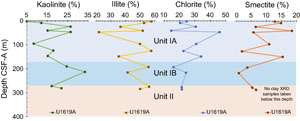

3.2. X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was used to characterize the clay mineral assemblage composed of kaolinite, illite, smectite, and chlorite in the uppermost 300 m at Site U1619 (Figure F9). The relative abundance of kaolinite ranges 5%–33%, with significant variations in the percentage of this clay mineral observed within Subunits IA and IB. There is an overall increase in kaolinite from the top of Subunit IA to the bottom of Subunit IB. Illite varies from 22% to 57%, with values averaging ~47%; a decrease in illite percentages occurs in Subunit IA down to ~46 mbsf, after which the values progressively increase downhole. Smectite shows a gradually decreasing trend in the clay assemblage from Subunit IA to IB, varying from 18% to 1% and showing a significantly lower average of 8% in Subunit IB. Chlorite exhibits a gradual decrease from Subunit IA to Subunit IB, ranging 46%–15%.

Additionally, bulk XRD analysis of select powdered samples confirms that clay minerals and quartz comprise the primary composition of the representative silty clay lithologies (Table T3). It also confirms the compositions of the suspected authigenic mineralogic components such as iron sulfides and iron carbonate (e.g., greigite and siderite, respectively) in Samples 403-U1619A-33X-3, 106–107 cm, 47X-3, 144–145 cm, and 52X-6, 70–71 cm, and carbonates in Sample 45X-5, 2–3 cm.

3.3. Preliminary interpretation

The fine-grained, bioturbated, and sometimes laminated sediments in Unit II suggest ongoing contouritic deposition by bottom currents during the Pliocene (and possibly since the Late Miocene). Occasional intervals of dispersed to common clasts (i.e., ice-rafted debris [IRD]) within Unit II (i.e., during the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene) may be evidence for short-duration glaciations and/or the early (and intermittent) establishment of regional ice caps that became the footholds for hemispheric ice sheet growth. According to chronostratigraphic constraints (see Biostratigraphy and paleoenvironment and Paleomagnetism), the lithostratigraphic boundary between Unit II and Subunit IB that is marked by an uphole increase in clasts may roughly correspond to the expansion of Northern Hemisphere glaciation (~2.7 Ma). Variations in clast abundance and changes in physical properties (e.g., NGR) over the length of Unit I is likely recording the variability of the paleo-SBSIS. Although sediments remain clast-rich at the Subunit IA/IB boundary, bioturbation decreases significantly uphole, potentially suggesting environmental/climate conditions negatively affecting benthic organisms after this time. The presence of authigenic carbonate minerals throughout Unit II and Subunit IB is similar to that observed at ODP Site 909, where carbonates originated in the Fe-reduction, suboxic zone, with additional dissolved carbon from oxidation of marine organic matter during the early stages of methanogenesis (Chow et al., 1996). This diagenesis seemingly decreases near the Subunit IB/IA boundary.

4. Biostratigraphy and paleoenvironment

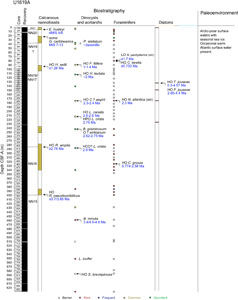

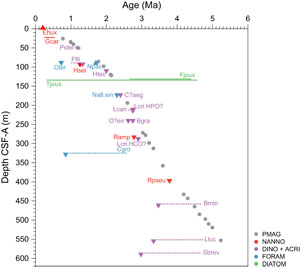

The sediments of Site U1619 were examined for calcareous nannofossils, planktonic foraminifers, diatoms, and dinoflagellate cysts (dinocysts). None of these microfossil groups are consistently present throughout the sediment column, and several levels are barren (Figure F10). Calcareous nannofossils appear intermittently across the entire sequence, within prolonged barren intervals. Diatoms are almost barren except for the core top and some intervals. Planktonic foraminifers are present in the upper part of Site U1619 and in intermittent intervals downcore. Dinocysts are present throughout the sediment column but are absent occasionally. All groups combined contribute to a first biostratigraphic and paleoenvironmental assessment and an age-depth model for Site U1619 (Figure F11; Table T4). Summary key events from all groups, together with paleomagnetic data, indicate that Site U1619 recovered the latest Miocene to the latest Pleistocene sediments.

The latest Pleistocene microfossil assemblages indicate Arctic to polar water with (seasonal) sea ice. Occasionally, the surface waters are influenced by warm Atlantic waters. Because of the many barren intervals and limited assemblage counts, no environmental conclusions could be made from the Early Pleistocene to Late Miocene sediments.

4.1. Calcareous nannofossils

The biostratigraphy of calcareous nannofossils at Site U1619 was produced from the analysis of all 85 core catchers across the site and 80 additional split core samples taken from the working halves (Figure F10). The position of split core samples was selected based on the combination of visual examination of sediments (i.e., color) and the shipboard physical properties of the sediments.

Calcareous nannofossils at Site U1619 are present intermittently between prolonged barren intervals (Figure F10). Nannofossil concentrations range between rare and abundant. Assemblages are characterized by an overall low diversity. The following 12 groups/taxa morphotypes were recognized in the assemblages at Hole U1619A: Emiliania huxleyi, small Gephyrocapsa, Gephyrocapsa caribbeanica, medium Gephyrocapsa, Pseudoemiliania lacunosa, small Reticulofenestra, medium Reticulofenestra, Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus 5–7 µm, R. pseudoumbilicus >7 µm, Coccolithus pelagicus, Calcidiscus leptoporus, and Helicosphaera sellii. Nannofossil preservation ranges between moderate and good. Reworked nannofossil specimens from older stratigraphic levels were not observed to be a prominent feature in the uppermost 22.79 m, but reworking is more prominent below 22.79 mbsf.

Four calibrated calcareous nannofossil events of the global zonation by Martini (1971) were identified at Site U1619 (Figure F10). For the Late Pleistocene, the revised calibrations and biochronology for the Arctic by Razmjooei et al. (2023) were additionally considered. For the Early Pleistocene and the Pliocene, calibration datums were selected according to the biostratigraphic approach in the region (i.e., ODP Leg 151 and Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 303). Complementary information, such as acme events, have been integrated into the calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphic scheme, contributing to placement of the sequence in Hole U1619A within the Late Pliocene to Pleistocene age (Figure F10).

The presence of E. huxleyi in the nannofossil assemblages is the main indicator of Zone NN21 (Martini, 1971). The lowest occurrence (LO) of this taxa has a global calibrated age of 291 ka, during MIS 8 (Thierstein et al., 1977; Rio et al., 1990; Raffi et al., 2006). However, in central Arctic regions, the LO of E. huxleyi is considered to have an age equivalent to MIS 5 (130 ka) (Razmjooei et al., 2023). For Hole U1619A, the LO of E. huxleyi is recorded in Sample 2H-1, 20 cm (Figure F10), allowing the identification of the lowermost MIS 8/MIS 5 boundary at 20 mbsf and the assignment of the uppermost part of the sequence at Site U1619 into Zone NN21 (Martini, 1971).

The species/morphotype G. caribbeanica is observed at 22.79 mbsf in Sample 403-U1619A-3H-CC (Figure F10). Based on its occurrence in the subtropical to subpolar latitudes of the Atlantic Ocean (Flores et al., 2012; González-Lanchas et al., 2023) and the Arctic (Razmjooei et al., 2023), an age between MISs 7 and 13 (191–524 ka) could be assigned to this stratigraphic level (Figure F10). The absence of the species P. lacunosa as a common component of the assemblage in this sample suggests an age younger than MIS 12 (430 ka), based on the highest occurrence (HO) of this species in the low Atlantic latitudes (Thierstein et al., 1977; Backman et al., 2012), or MIS 13 (474 ka), based on its HO in the Arctic (Razmjooei et al., 2023). Thus, Sample 3H-CC belongs to Zone NN20 (Martini, 1971) (Figure F10).

The species H. sellii is present from Sample 403-U1620A-11H-CC at 93.25 mbsf (Figure F10). According to the calibration of Sato and Kameo (1996) in the Fram Strait region, the HO of this species corresponds to an age of 1.26 Ma (Figure F10). Below this boundary to 112.17 mbsf, barren intervals alternate with somewhat productive or better preserved intervals where C. pelagicus is observed. According to Sato and Kameo (1996), this part of the sequence could correspond to any part of the interval between 1.72 and 2.78 Ma (Figure F10).

Specimens belonging to the genus Reticulofenestra are common in the assemblage from Sample 403-U1619A-34X-CC downward (Figure F10). According to Sato and Kameo (1996), this could be indicative of a Pliocene age. In particular, the species Reticulofenestra amplia is observed within the medium Reticulofenestra group from this sample downward in the sequence, indicating an age of 2.78 Ma (Sato et al., 1999) and Zone NN16 in this part of the sequence (see Figures F14 and F17 in the Expedition 403 Site U1620 chapter [St. John et al., 2026]). Based on this information, the interval between the HO of H. sellii and the HO of R. amplia (93.25–242.33 mbsf) could be assigned to Zones NN19–NN16 (Martini, 1971).

The species R. pseudoumbilicus >7 µm is observed in Sample 403-U1619A-55X-CC (Figure F10). The HO of this nannofossil species is a globally calibrated event with an age of 3.7 Ma (Lourens et al., 2004). Biostratigraphic nannofossil studies from subpolar latitudes in the North Atlantic latitudes (i.e., Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expeditions 303/306) corroborate the calibration of 3.85 Ma by Sato et al. (1999). According to these determinations, an age older than 3.7/3.85 Ma can be assigned to this stratigraphic level (Figure F10). Furthermore, the identification of this age boundary places the interval from 398.8 to 627.9 mbsf in Zone NN15 of Martini (1971).

4.2. Diatoms and silicoflagellates

The study of diatoms at Site U1619 is based on the examination of 154 samples taken from the core catcher and additional samples from split core sections. The analyses revealed that Site U1619 is almost barren of diatoms, except the uppermost sections of Hole U1619A and the occasional downcore samples that contain diatoms and/or diatom fragments. In general, the diatom abundance, on those samples containing entire diatoms, varies from common to trace. Preservation is good to poor.

Diatoms are present in Samples 403-U1619A-1H-1, 0 cm, and 1H-1, 40 cm, between 0 and 0.4 mbsf and in Samples 2H-1, 1 cm, 2H-1, 3 cm, 2H-1, 4 cm, and 2H-1, 20 cm, between 3.41 and 3.60 mbsf. In these samples, a well to moderately preserved diatom assemblage is found (Figure F10). The diatom assemblage represents paleoenvironmental conditions similar to those observed today in surface sediments in the Nordic Seas. The most abundant taxa are Chaetoceros in resting spore stage (RS), Fragilariopsis oceanica, Fragilariopsis cylindrus, Coscinodiscus marginatus, Coscinodiscus radiatus, Thalassionema nitzschioides var. nitzschioides, Rhizosolenia hebetata f. hebetata, Shionodiscus oestrupii, Thalassiosira antarctica var. borealis, Bacterosira bathyomphala, and the tychopelagic diatoms Delphineis surirella, Odontella aurita, and Paralia sulcata, which together represent a characteristic assemblage of the study area. The species Neodenticula seminae is not observed at this site.

Deeper in Hole U1619A, four intervals with diatom abundance from trace to common are also observed in Samples 19F-1, 79 cm (132.09 mbsf), 22F-CC (149.815 mbsf), 25X-CC (174.735 mbsf), and 32X-CC (226.945 mbsf). Except for the first sample, they all contain traces of a poor assemblage formed by highly silicified diatoms (P. sulcata and D. surirella). On the other hand, Sample 19F-1, 79 cm (132.09 mbsf), contains a diverse diatom assemblage with species such as Chaetoceros RS, C. marginatus, C. radiatus, F. cylindrus, P. sulcata, T. nitzschioides var. nitzschioides, and T. antarctica var. borealis. The sample contains traces of two biostratigraphic markers, Thalassiosira jouseae and Fragilariopsis jouseae. T. jouseae has a temporal distribution from 4.57 Ma (LO) to 0.3 Ma (HO) and F. jouseae from 4.4 Ma (LO) to 2.65 Ma (HO) (Baldauf, 1987; Koç and Scherer, 1996; Koç et al., 1999). The biostratigraphic and paleomagnetic data generated on board suggest that for Site U1619 this depth should be older than 2.65 Ma and younger than 4.4 Ma.

No silicoflagellates were observed at Site U1619.

4.3. Dinoflagellate cysts and acritarchs

The samples (21) analyzed from Hole U1619A indicate an Early Pliocene (possibly Late Miocene) to latest Pleistocene age. A total of 43 different taxa were encountered. Samples contain few taxa, ranging between 1 and 12 taxa per sample. The number of taxa decreases downhole, which may be an artifact of the nonacid preparation technique, which proved more difficult to extract palynomorphs from the denser lithology in the lowermost part of the hole. Autotrophic taxa are dominant only in the two upper samples (403-U1619A-1H-CC and 2H-1, 20–21 cm). Autotrophic taxa are only rarely found below Sample 30X-CC (i.e., in the Pliocene). On the other hand, small acritarchs are most frequently recorded here.

In the uppermost part of the record, a Late Pleistocene, warm, Atlantic water–dominated assemblage (de Vernal et al., 2020) was encountered in Sample 403-U1619A-2H-1, 20–21 cm.

We recorded Protoperidinium stellatum in high abundance in Sample 403-U1619A-5H-4, 55–56 cm, and it also occurs in Sample 5H-6, 55–56 cm. This species is found around the Jaramillo Subchron at Sites U1618, U1620, and U1623 and ODP Hole 911A (Matthiessen and Brenner, 1996). Its presence around the Jaramillo Subchron may mark its first appearance in the record (Van Nieuwenhove et al., 2020), and it is a good regional biostratigraphic marker for the Fram Strait and potentially the Arctic Ocean.

Filisphaera filifera is present in low numbers in two consecutive samples, with Sample 403-U1619A-10H-CC recording its HO. The F. filifera acme was not identified here, but the HO suggests a maximum age of 1–1.4 Ma (Matthiessen et al., 2018).

Habibacysta tectata is recorded in Samples 403-U1619A-14F-CC, 34X-CC, and 40X-CC. It is the dominant species in Sample 14F-CC, which is also the HO in Hole U1619A. It is likely that this sample corresponds to the highest persistent occurrence (HPO) of H. tectata rather than its HO. In the high-latitude North Atlantic to Arctic region, its HPO occurs around the Olduvai, estimated around ~2 Ma (Matthiessen et al., 2018).

The acritarch Cymatiosphaera? aegirii (HO in Sample 403-U1619A-25X-CC) has a range between 5.62 and ~3 Ma at ODP Site 642, Norwegian Sea, but a range top could not be determined at that site. In the North Atlantic, it occurs between 3.35 and 2.42 Ma (De Schepper and Head, 2014), whereas a recent study shows its HPO at 2.33 Ma in the Labrador Sea (Aubry et al., 2020).

The acritarch Lavradosphaera canalis occurs in Sample 403-U1619A-30X-CC. This acritarch has a very narrow stratigraphic range in the North Atlantic between 2.6 and 2.8 Ma (De Schepper and Head, 2014; Aubry et al., 2020). The uppermost record of Lavradosphaera crista was questionably identified in Sample 30X-CC and could tentatively be linked to its HPO around 2.75 Ma (De Schepper and Head, 2014; Aubry et al., 2020). The record in Sample 30X-CC could correspond to its HPO, suggesting an age of 2.75 Ma (Aubry et al., 2020). Finally, Trinovantedinium sp. A was recorded in the sample. This species was previously reported at Site U1618 (see Figure F17 in the Expedition 403 Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b]) and in the Late Pliocene (~2.7 Ma) of Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Bering Sea Site U1341 (S. De Schepper, unpubl. data, 2024).

Several Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene taxa are present in Sample 403-U1619A-34X-CC. Barssidinium graminosum has its HO in Sample 34X-CC. B. graminosum is recorded in the Early Pleistocene St. Erth Beds (England), but in the more open ocean Pliocene North Atlantic and Nordic Seas it has a range top around 2.75 Ma (Aubry et al., 2020; De Schepper et al., 2017; De Schepper and Head, 2008, 2009). Operculodinium? eirikianum has a range top at 4.5 Ma in the Iceland Sea (Schreck et al., 2012), 3.16 Ma in the Labrador Sea (Aubry et al., 2020), and 2.62 Ma in the North Atlantic (De Schepper and Head, 2008, 2009). In the Norwegian Sea, it is present up to ~3 Ma, but a range top could not be identified there. Using the most conservative age estimate for the range top would indicate an age not younger than 2.62 Ma. In summary, Sample 34X-CC is likely not younger than 2.62–2.75 Ma.

L. crista is positively identified in Sample 403-U1619A-40X-CC. The number of acritarch specimens is too low in our counts to unquestionably determine whether this corresponds to its highest common occurrence (HCO). Nevertheless, here we tentatively assigned this level as its HCO, which is reported at ~2.9 Ma (De Schepper and Head, 2014; Aubry et al., 2020). Ataxiodinium confusum is also present in Sample 40X-CC. This species confirms a Late Pliocene age for this sample because it has a range top at 2.62 Ma in the North Atlantic (De Schepper and Head, 2008, 2009).

Sample 403-U1619A-47X-CC contains two specimens of Selenopemphix islandensis, a species described from the Serripes Biozone in the Tjörnes section in Iceland (Verhoeven and Louwye, 2012). Several age models have been published for this section, and these either place the Serripes Zone in the Late Pliocene (older than ~3 Ma) or in the Early Pliocene (older than 4–4.5 Ma) (e.g., Hall et al., 2023). A conservative age estimate for the occurrence of S. islandensis in Sample 47X-CC would thus be older than 3 Ma.

Batiacasphaera minuta/micropapillata is a well-known marker in the Early Pliocene and occurs in Sample 403-U1619A-63X-CC. It has a range top in the Labrador Sea around 3.6 Ma and in the eastern North Atlantic at 3.83 Ma (De Schepper and Head, 2008, 2009). In the Iceland Sea, it has a HO at 3.42 Ma and a HPO at 4.55 Ma (Schreck et al., 2012). The latter is comparable to the HO in the Norwegian Sea, where it disappears from the record around 4.64 Ma (De Schepper et al., 2015, 2017).

We recorded the acritarch Lavradosphaera lucifer in Sample 403-U1619A-75X-CC. This species has a known stratigraphic range from the mid-Tortonian (Upper Miocene) of the Labrador Sea through the lower Piacenzian (3.2–3.3 Ma) of the eastern North Atlantic (De Schepper and Head, 2014). In the Norwegian Sea, it has a HO at 4.69 Ma (De Schepper et al., 2017).

The lowermost Samples 403-U1619A-80X-CC and 85X-CC contain only the heterotrophic taxa Selenopemphix conspicua, Selenopemphix brevispinosa, Lejeunecysta spp., Trinovantedinium variabile, and round brown cysts. The HO of S. brevispinosa is in Sample 80X-CC. The species is common in the Miocene and has a range top at 4.64 Ma in the Norwegian Sea, but occurrences are reported up to the Late Pliocene around the North Atlantic (De Schepper et al., 2017; De Schepper and Mangerud, 2017).

4.4. Foraminifers

All core catcher samples from the uppermost 220 m of Hole U1619A were analyzed for planktonic foraminifers. An additional 25 core catcher samples below 220 mbsf were analyzed, with special focus on the interval 288–347 mbsf. Planktonic foraminifers are present in intermittent intervals throughout Hole U1619A with rare to frequent abundances, but from ~400 mbsf downcore the analyzed samples are barren (Figure F10). Preservation is moderate with some abrasion/dissolution and/or entrustment. None or very few fragments were observed.

Neogloboquadrina atlantica (sin) is present in all samples from ~400 to 174 mbsf, where this species has its HO (Figure F10). The coiling directions of N. atlantica are an integral part of its use as a biomarker, and the HO of N. atlantica (sin) in the North Atlantic and Norwegian Sea occurs at 2.3 Ma (Spiegler and Jansen, 1989; Weaver and Clement, 1986). Neogloboquadrina pachyderma arises from N. atlantica, and its left-coiled form has been found in the North Atlantic and Norwegian Sea from 1.7 Ma (Spiegler and Jansen, 1989; Weaver and Clement, 1986). In Hole U1619A, the LO of N. pachyderma is at 89.65 mbsf. However, this LO appears after several barren intervals and could be lower in Hole U1619A (Figure F10). N. atlantica (dex) has also been observed in Hole U1619A at 302.11 mbsf. Spiegler and Jansen (1989) suggested two biozones (upper and lower) in the Pliocene based on N. atlantica (dex); however, N. atlantica (dex) is only found in one sample at Site U1619, and it is not possible to establish whether it represents any biozones.

Two additional biostratigraphic markers were identified based on benthic foraminifers in Hole U1619A. Cibicides grossa is present in the lower part of Hole U1619A, and its HO is at 324.95 mbsf. This event is diachronous and occurs between 0.774 and 2.58 Ma in the North Atlantic and Nordic Seas (Anthonissen, 2008). Another benthic foraminiferal event is the HO of Cassidulina teretis, which occurs at 0.733 Ma in the North Atlantic and Nordic Seas (Seidenkrantz, 1995). This event was observed at 89.65 mbsf (Figure F10).

Planktonic foraminifers are consistently present in the upper part of Hole U1619A, and the fauna consists of N. pachyderma. Planktonic foraminiferal assemblages in the Arctic often consist of this species found within Arctic to polar water masses with/without seasonal sea ice (e.g., Husum and Hald, 2012; Pados and Spielhagen, 2014).

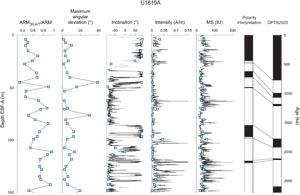

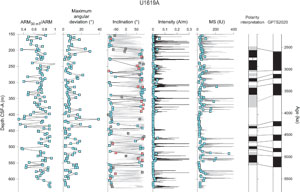

5. Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetism investigation of Site U1619 focused on measurements of natural remanent magnetization (NRM) before and after alternating field (AF) demagnetization of archive-half sections and vertically oriented cube samples. All archive-half sections were measured except a few that had significant visible coring disturbance and the core catchers. Some archive-half sections with high MS (above ~750 IU) were too strong for the NRM to be measured on the superconducting rock magnetometer (SRM) and caused flux jumps even when the track speed was slowed by 10×, thus compromising our ability to collect quality data in these intervals. However, the intensity often was reduced after AF demagnetization, and measurements could then be made.

APC and HLAPC archive-half sections were measured before and after 10 and 20 mT peak AF demagnetization. Because XCB cores do not use nonmagnetic core barrels and are more susceptible to the viscous isothermal remanent magnetization (VIRM) drill string overprint (Richter et al., 2007), XCB archive-half sections required higher AF demagnetization steps to remove this overprint and were measured before and after 15 and 30 mT peak AF demagnetization. The NRM of the oriented discrete cube samples were stepwise demagnetized to 50 mT using the in-line AF demagnetizing system of the SRM. These measurements were supplemented by measurement of MS and anhysteretic remanent magnetization (ARM) on all samples. Select samples were given isothermal remanent magnetizations (IRMs) at 100, 300, and 1000 mT direct current fields and −100 and −300 mT backfield direct current fields. Two intact but unoriented iron sulfide nodules were also sampled and subjected to NRM AF demagnetization, MS, ARM, IRM, XRD, and scanning electron microscope/energy dispersive spectrometry (SEM/EDS) analyses.

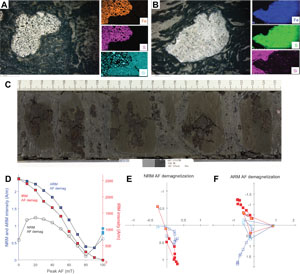

5.1. Sediment magnetic properties

Site U1619 has similar magnetic properties to Site U1618 (see Paleomagnetism in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b]) that likely reflect contribution from detrital and authigenic sources. Although sediments are mostly lithogenic in origin (see Lithostratigraphy) and magnetic characterization of the uppermost samples is consistent with (titano)magnetite, rock magnetic data and visual evaluations of the split core surfaces indicate that authigenic iron sulfides are also present. These iron sulfide minerals sometimes occur as nodules that are centimeter scale in diameter or are associated with infilled burrows. In some cases, the former type of massive nodule is associated with the highest observed MS values at Site U1619, including values >1000 IU and up to ~4500 IU measured on the WRMSL. MS values greater than 500 IU become common below about 165 mbsf (Figure F19), and these intervals are often associated with high-density materials in X-ray images and black to gray nodules on the split core surface. Two intervals with visible iron sulfide nodules were studied in greater detail. The first was an infilled burrow (Core 403-U1619A-32X; 220.92 mbsf) with lower MS (60–80 IU in the surrounding centimeter) measured on the WRMSL (Figure F12A). Thin section analysis of this deposit showed that these have sand-sized silicate minerals included within the iron sulfide and are consistent with pyrite-infilled burrows. The second was from an interval with concentrated centimeter-scale nodules (Core 33X; ~229.1–225.3 mbsf) with high MS values in this interval that range ~1800–4300 IU (measured on the WRMSL) (Figure F12B–F12F). In thin section, these nodules were massive and uniform in composition, and XRD analysis found their composition to be 99.5% greigite (Figure F12B). More detailed magnetic measurements of a subsample of the nodule confirmed the strong magnetization and showed similar magnetic properties to the previously studied nodule from Core 403-U1618B-25X (see Paleomagnetism in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b]). Although still quite resistant to AF demagnetization, magnetic measurements indicate this nodule had slightly lower coercivity than the nodule measured at Site U1618, with a ratio of the ARM after 30 mT peak AF demagnetization to the initial ARM (ARM30mT/ARM) of 0.86, ARM median destructive field of 59.6 mT, and IRM median destructive field of 54.4, but it also had an S-ratio of 1 (IRM after a 300 mT backfield normalized by a saturating IRM at 1000 mT; Stober and Thompson, 1979) (Figure F12D; Table T5), consistent with previously reported magnetic properties for sedimentary greigite (Peters and Thompson, 1998; Roberts et al., 2011; Horng, 2018). Although the Site U1618 sample crumbled and was mounted as randomly oriented particles, the Site U1619 sample was removed and mounted as an intact piece, allowing us to also study the NRM of the nodule. The NRM contained two roughly antiparallel components, which resulted in apparent acquisition up to 20 mT peak AF demagnetization (Figure F12D, F12E). This is likely explained as a VIRM drill string overprint (Richter et al., 2007). Because the VIRM typically induces a magnetization consistent with a steep positive inclination, the antiparallel nature may indicate that the nodule hosts a reverse magnetization. At high peak AF, the NRM acquired a magnetization in the horizontal plane perpendicular to the Z (vertical) orientation of the last applied AF, consistent with a gyroremanent magnetization (GRM). Interestingly, AF demagnetization of the ARM also showed remanence acquisition in the horizontal plane of a similar magnitude at high AF (Figure F12F). After 100 mT peak AF demagnetization in the +X-, +Y-, and then −Z-directions, following the approach of Stephenson (1993), we subjected the sample to 100 mT peak AF demagnetization in the −X, −Y, and +Z orientations, measuring the sample after each step. In each case, the sample acquired a remanence in the plane perpendicular to the last applied AF, confirming that the sample was acquiring a GRM.

The magnetic properties of 150 vertically oriented sediment cube samples provide insight to the magnetic mineralogy that hosts the NRM. ARM coercivity, tracked by the ARM30mT/ARM ratio, shows a wide range of values from 0.31 to 1.00 and has a bimodal distribution, with modes centered around 0.45 and 0.72 (Figure F13). Values nearest the sediment water interface and above the depths of the first near-zero interstitial water sulfate value around 18.7 mbsf (Figure F29) have an average ARM30mT/ARM ratio of 0.48 (n = 4) and are consistent with values expected for detrital (titano)magnetite assemblages. Previous work has indicated that both greigite and magnetite can have a wide range of ARM coercivities but greigite values are generally greater (Peters and Thompson, 1998). Thus, based on our direct observation of Site U1618 and U1619 Vestnesa Ridge greigite nodules with an average ARM30mT/ARM ratio of 0.89 (n = 2) and near-surface sediments above sulfate reduction depths of 0.46 (n = 8), we interpret this wide range of ARM coercivities to reflect varying contribution of greigite (high ARM30mT/ARM) versus detrital magnetic minerals (lower ARM30mT/ARM). Comparison with IRM data indicates that Vestnesa Ridge magnetic mineral assemblages may be more complex than just two components, and the ARM30mT/ARM does not show a clear linear mixing with other rock magnetic parameters, such as the 100 mT IRM/300 mT IRM (IRM100/IRM300) ratio or the saturation isothermal remanent magnetization (SIRM)/ARM ratio (Figure F13). Nearby Site U1618 shows many samples with a harder IRM acquisition coercivity (low IRM100/IRM300 ratios) and also samples with low S-ratios, indicating that hematite and/or pyrrhotite may be present in varying concentrations. Comparison of SIRM/ARM and ARM30mT/ARM ratios indicates presence of a magnetic mineral with high ARM coercivity and low IRM intensity relative to ARM intensity. These magnetic properties are not consistent with our limited observation of the greigite nodules, our estimate for the primary detrital assemblage, or samples with low S-ratios (Figure F13). However, the samples with high SIRM/ARM values are associated with high MS and may be important for understanding the paleomagnetic record at Site U1619 and how formation of the greigite nodules may influence its fidelity. Thus, further work using temperature-dependent, in-field, mineralogical, and SEM/EDS methods will be needed to gain a more complete understanding of the magnetic minerals present at these Vestnesa Ridge sites (U1618 and U1619).

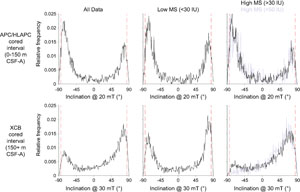

5.2. Natural remanent magnetization

Of NRM intensities at Site U1619, 95% are between 1.0 × 10−3 and 4.1 × 10−1 A/m, with APC/HLAPC sections between 2.0 × 10−4 and 6.6 × 10−2 A/m after 20 mT peak AF demagnetization and XCB sections between 1.0 × 10−4 and 8.8 × 10−2 A/m after 30 mT peak AF demagnetization. Following the 20 mT AF demagnetization step, the distributions of measured inclinations from APC/HLAPC cores have a pronounced bimodal distribution with peaks at −76° and 78°, slightly less than the ±84.5° predicted for a geocentric axial dipole (GAD) field at this latitude (Figure F14). Following the 30 mT AF demagnetization step, the distributions of measured inclinations from XCB cores also have a bimodal distribution with peaks at −76° and 76°, but it is less pronounced and has significantly more values at intermediate inclinations, between ±45°. This may be related in part to the difference in coring disturbance, core quality, and VIRM drill string overprint between the APC/HLAPC and XCB methods, but it may also reflect other complications related to NRM acquisition below 165 mbsf where very high MS values (above 500 IU) become common and greigite nodules are commonly observed on the split core surface. We observe that in the XCB-cored interval the distribution of measured inclination in intervals with low MS (<30 IU) shows a more pronounced bimodal distribution that is more similar to the distribution observed for APC/HLAPC cores (Figure F14). Conversely, the distribution of MS values from intervals with MS higher than 30 IU is not strongly bimodal and instead is a skewed distribution with a peak around 70° and a significant amount of values at intermediate inclinations. Intervals with MS higher than 50 IU do not have any peak at steep negative inclinations. APC/HLAPC cored intervals (all shallower than 150 mbsf) do not show a significant difference between low and high MS intervals. Based on these observations, our rock magnetic investigation, and the visual and XRD observation of large greigite nodules associated with high MS, we suspect that low MS intervals have the best chance to record a high-fidelity remanent magnetization. Like nearby Site U1618 (see Paleomagnetism in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b]), we suspect that many intervals at Site U1619 may be remagnetized by a late-forming chemical remanent magnetization (CRM) that would be younger than the detrital remanent magnetization of the surrounding sediments. Further work is needed to fully characterize the remanence carriers at Site U1619 and their implications for the fidelity of our magnetostratigraphic interpretation.

5.3. Magnetic stratigraphy

Because of the clear evidence for authigenic greigite at Site U1619 and the wide range of sediment magnetic properties that indicate a complex mixture of authigenic and detrital minerals, we recognize the potential for late-forming CRMs and interpret Site U1619 paleomagnetic data cautiously. Although there are uncertainties that we are not able to fully assess at this stage, shipboard analysis indicates great potential for future evaluation and refinement of the magnetic stratigraphy with additional sampling and detailed study of Site U1619 remanence carriers. To guide our magnetostratigraphic interpretation, we began by locating polarity boundaries between our discrete cube samples and then further refined the top and bottom depth range using archive-half data if possible (Figures F15, F16). Polarity boundaries are provided in Table T6 with top and bottom depths indicating the uncertainty range of our estimates and midpoint of this range. Depth uncertainty varies considerably from <1 to 40 mbsf.

The Chron C1n onset (Matuyama/Brunhes boundary; 773 ka) was recovered in heavily disturbed Core 403-U1619A-4H, which experienced a split liner and was extruded on the drill floor (Figure F15). The archive section half data show a clear transition from positive to negative inclinations downcore, and we define the boundary using two discrete cube samples that were taken from intervals that visually had minimal disturbance (midpoint = 25.89 mbsf). The subchrons of the Matuyama are fairly well defined in archive-half data between Cores 5H and 17F, with excellent definition of Subchrons C1r.1n (Jaramillo; 990–1070 ka) and C2n (Olduvai; 1775–1925 ka). The shorter Subchrons C1r.2n (Cobb Mountain; 1180–1215 ka) and C2r.1n (Feni; 2116–2140 ka) are identified; however, noisy directions above where we identify C1r.2n and above and below C2r.1n may require additional investigation to evaluate if this variability is geomagnetic, related to core disturbance, or related to potential remagnetization.

MS peaks that could be associated with greigite nodules become more common in the XCB interval, and typical XCB coring disturbance added significant noise to the archive-half paleomagnetic measurements (Figure F16). However, the discrete cube samples with well-defined characteristic remanent magnetizations (ChRMs) are typically always steep and negative or steep and positive, consistent with what would be expected at these latitudes for a GAD. In our interpretation, we avoid samples with higher MS (>5 IU) because these have a greater possibility of influence from the high-MS greigite nodules. The discrete cube samples we use in our interpretation are mostly normal between ~200 and 340 mbsf and mostly reverse between 380 and 430 mbsf and from 560 mbsf to the base of recovery, with an interval of alternating polarity between 430 and 560 mbsf. We broadly interpret this pattern to represent Chrons C2An (Gauss; 2595–3596 ka), C2Ar (upper Gilbert; 3596–4187 ka), C3n (middle Gilbert; 4187–5235 ka), and C3r (lower Gilbert; 5235–6023 ka) (Figure F16). The largest uncertainty of these chron boundaries is associated with the onset of Chron C2An (Gilbert/Gauss boundary; 3696 ka) for which there is an interval between 338.01 and 377.62 mbsf with cube sample ChRM inclinations and archive-half inclinations that flip between normal and reverse polarity. Reverse polarity within Chron C2An (Gauss) defined by multiple samples are interpreted to be the C2An.1r (Kaena; 3032–3110 ka) and C2An.2r (Mammoth; 3207–3330 ka) Subchrons. Four normal polarity intervals within Chron C3n (middle Gilbert) are interpreted to be Subchrons C3n.1n (Cochiti; 4187–4300 ka), C3n.2n (Nunivak; 4493–4631 ka), C3n.3n (Sidufjall; 4799–4896 ka), and C3n.4n (Thvera; 4997–5235 ka). In both cases, our placement of these subchron sequences indicate fairly linear accumulation rates within Chrons C2A and C3 (Figure F17). Given the discussed uncertainties, the exact placement of the reversal boundaries will need to be tested and refined during postcruise research.

The Site U1619 magnetic stratigraphy indicates that we recovered a sequence capturing the entire Pliocene and Pleistocene that is particularly expanded during the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The base of recovery captured sediments deposited in the latest Miocene during Chron C3r (lower Gilbert), younger than 6023 ka. In the current geologic timescale (Gradstein et al., 2020), the Miocene/Pliocene boundary is located five precession-related cycles below the onset of Subchron C3n.4n (Thvera), whose boundary we identify between 548.32 and 557.5 mbsf. Long-term accumulation rates change by a factor of ~5 and can be described with four linear segments with good fit to our magnetic stratigraphy interpretation (Figure F17). We estimate long-term accumulation rates are ~3 cm/ky (0.0–1.0 Ma), ~7 cm/ky (1.0–2.0 Ma), ~16 cm/ky (2.0–3.8 Ma), and ~11 cm/ky (3.8–5.9 Ma).

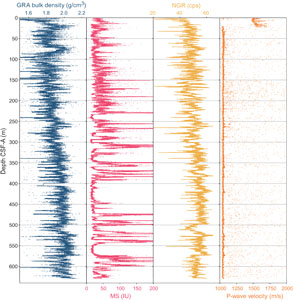

6. Physical properties

The physical properties measured shipboard for Site U1619 included nondestructive whole-round measurements using the Special Task Multisensor Logger (STMSL), WRMSL, and Natural Gamma Radiation Logger (NGRL), as well as thermal conductivity and discrete P-wave velocity measurements on working-half sections after cores were split. GRA bulk density and MS were measured on the STMSL immediately after core recovery and then on the WRMSL after thermally equilibrating for a minimum of 4 h. Core 403-U1619A-56X was excluded from GRA bulk density measurements due to its selection for sedimentary ancient DNA (sedaDNA) sampling and the need to avoid exposure to the radioactive cesium source. Physical properties data from the STMSL were used for initial site-to-site stratigraphic correlation (see Stratigraphic correlation) to aid in near-real-time drilling and sampling (e.g., sedaDNA and biostratigraphic smear slide sampling) decisions but are not further evaluated and reported here. Further use of STMSL data is discouraged because WRMSL and SHMSL data, collected after allowing for thermal equilibration, are available in the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) database. Aside from one 10 cm interval that was sampled for anelastic strain recovery (ASR) analysis, P-wave velocity was measured on the WRMSL for all core sections. Results from whole-round scans are compiled in Figure F18. Whole-round physical property data were also used for stratigraphic correlation and splicing (see Stratigraphic correlation).

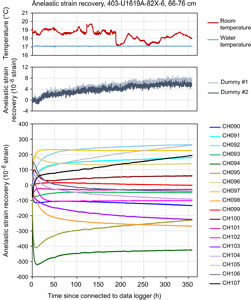

Discrete P-wave measurements were initially made on Sections 403-U1619A-2H-3 and 3H-4 using the Section Half Measurement Gantry (SHMG). However, below these cores, SHMG measurements ceased due to poor data quality. Thermal conductivity measurements were made on all Hole U1619A cores using a puck probe on the split face of working-half sections. Working-half sections from Hole U1619A were sampled for moisture and density (MAD) analyses. Intervals with minimal coring disturbances were targeted for MAD sampling. Archive halves were measured with the SHMSL for MS and color reflectance and X-ray scanned using the X-Ray Linescan Logger (XSCAN) (see Lithostratigraphy). One 10 cm interval from Section 403-U1619A-82X-6 (66–76 cm) was selected and sampled for ASR measurements.

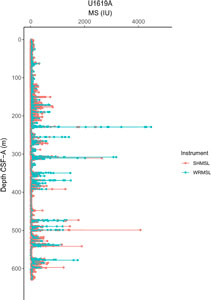

6.1. Magnetic susceptibility

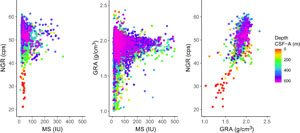

MS was measured on whole-round sections using a pass-through loop sensor on the WRMSL track and on split archive-half sections using a point-source sensor on the SHMSL track. Sections were measured at 2.5 cm increments on the WRMSL and 5 cm increments on the SHMSL. WRMSL and SHMSL MS measurements yielded similar values and downhole variability (Figure F19). MS values range 0.71–4471.87 instrument units (IU). The average MS values for both WRMSL and SHMSL data are significantly lower than the maxima, with 49.57 IU for WRMSL and 36.95 IU for SHMSL.

In the uppermost interval, from the seafloor to ~150 mbsf, MS is generally low, with a WRMSL-derived average of ~36.68 IU. Below ~150 mbsf, large MS peaks appear in the record; below ~225 mbsf, MS peaks become higher in magnitude, with values reaching from several hundred to several thousand instrument units. These outsized peaks in MS are often associated with nodules of authigenic iron sulfide minerals (e.g., greigite identified in rock magnetic and XRD analyses) (see Lithostratigraphy, Geochemistry, and Paleomagnetism). These peaks do not exhibit a correspondence in the NGR or GRA bulk density profiles (Figure F20), indicating that magnetically strong constituents are hosted in material with variable composition and degree of compaction. Below ~240 mbsf, several intervals of low MS (<50 IU) occur, both within units of higher NGR and GRA bulk density (e.g., ~400–425 mbsf) and units of lower NGR and GRA bulk density (e.g., ~500–525 mbsf).

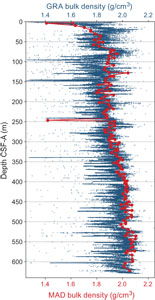

6.2. Gamma ray attenuation bulk density

Except for Core 403-U1619A-56X, which was sampled for sedaDNA, every whole-round section was measured at 2.5 cm intervals on the WRMSL. Excluding outliers related to voids or coring disturbances, measured GRA bulk density values range ~1.6 to ~2.1 g/cm3, with a strong mode at ~1.8–1.9 g/cm3. Values increase rapidly from the seafloor (~1.6 g/cm3) to ~20 mbsf (1.8–1.9 g/cm3), and the overall GRA bulk density trend is toward higher values downcore (Figure F18), consistent with sediment compaction at depth. GRA bulk density values have a positive linear correlation with NGR (Figure F20). The bulk density record shows the widest range of variability in the uppermost ~150 m, corresponding to Lithostratigraphic Subunit IA. Below ~150 mbsf, GRA bulk density is less variable, which may be associated with the transition to XCB cores.

6.3. Natural gamma radiation

NGR was measured on all whole-round core sections at 10 cm intervals. Measured NGR values range ~19 to ~65 counts/s (average = 51 counts/s) (Figure F18). Throughout Hole U1619A, NGR variability appears to be cyclic, with some changes in the amplitude of the variability and the average values downhole. From ~10 to 300 mbsf, variability is of greater amplitude, ranging ~20–65 counts/s. Between ~300 and 500 mbsf, NGR variability is of lower amplitude, ranging 25–65 counts/s and centered around a mode of 54 counts/s. A broad interval of low NGR occurs from ~500 to 530 mbsf, below which depth there is an interval of higher NGR from ~530 to 570 mbsf. From ~570 mbsf to the base of Hole U1619A, NGR returns to lower amplitude variability centered around a mode of 52 counts/s. These trends are also present in GRA bulk density, although the GRA density trends are somewhat muted by the gradual downcore increase in density. A linear relationship between GRA bulk density and NGR is clear (Figure F20), split between a shallower population in the interval ~0–50 mbsf and deeper sections from ~60 mbsf to the base of Hole U1619A. NGR was important for identifying relationships between physical properties and lithostratigraphy, especially because the MS data were interspersed with authigenic iron sulfide peaks and GRA density measurements were omitted in one of the cores.

6.4. P-wave velocity

Whole-round sections were measured for compressional P-wave velocity on the WRMSL at a resolution of 2.5 cm for all core sections from Site U1619. Values predominantly range between 1500 and 1700 m/s in the uppermost 20 m. Below ~20 mbsf, the signal becomes dominated by noise and values were mostly outside of the typical range expected for marine sediments. Persistent issues with void spaces and gas expansion, which required reinforcing the core liners, along with the switch to XCB cores led to variability in liner thickness and core diameter. This compromised P-wave velocity calculations from WRMSL measurements (see Physical properties in the Expedition 403 methods chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026a]). P-wave velocity data below ~20 mbsf should not be used.

Discrete P-wave measurements were made using the SHMG in intervals that excluded excessive coring disturbances, voids, cracks, or large clasts. Measurements were made for Sections 403-U1619A-2H-3 and 3H-4. Because of noise in the signal, P-wave velocity waveforms were manually selected. Values range from ~1490 m/s at the seafloor to ~1600 m/s at ~20 mbsf. Below ~20 mbsf, however, P-wave measurements on the SHMG were abandoned due to increasing noise and eventual lack of a detectable signal. We suspect the abundance of large clasts (IRD) and authigenic mineral formations (e.g., greigite nodules and authigenic carbonates), as well as free gas trapped in isolated pore spaces, contribute to signal depletion below ~20 mbsf.

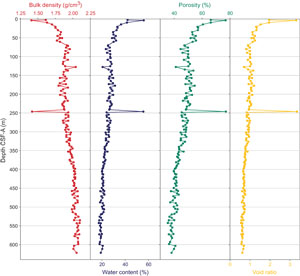

6.5. Moisture and density

MAD analyses were conducted using 146 discrete samples collected from the working section halves of split cores from Hole U1619A (see Physical properties in the Expedition 403 methods chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026a]). Several parameters, including porosity, water content, and bulk density, were calculated using the measurements of wet mass, dry mass, and volume from samples (Figure F21). Notable low bulk density values of ~1.4 g/cm3 are captured in both MAD and GRA bulk density (Figure F22) at ~245 mbsf, close to the boundary between Lithostratigraphic Subunit IB and Unit II (see Lithostratigraphy). This low is likely related to increased biscuiting and may not represent in situ sediments. MAD bulk density increases downcore from ~1.6 g/cm3 at the sediment surface to ~1.8 g/cm3 at ~40 mbsf, likely related to sediment compaction. Bulk density increase occurs in parallel with decreasing porosity (66% to 53%), water content (42% to ~30%), and void ratio (1.9 to 1.1). From ~40 mbsf to the base of Hole U1619A, MAD bulk density ranges 1.4–2.1 g/cm3 (average = ~1.9–2.0 g/cm3). Overall MAD bulk density values increase downcore. Highest MAD bulk density values are found from ~530 mbsf to the base of Hole U1619A, with an average of ~2.1 g/cm3. MAD bulk density values have a negative correlation with the other MAD parameters and correspond well to GRA bulk density trends downcore.

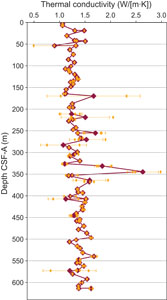

6.6. Thermal conductivity

To calculate heat flow and interpolate temperature data, thermal conductivity measurements were made using the TK04 system for one section per core from Hole U1619A. A puck contact probe was placed on the split face of working section halves. To ensure good contact with the probe, a small amount of deionized water was added and/or the face was swept with a spatula. Homogeneous intervals lacking large clasts, voids, cracks, and sediment disturbances were targeted (see Physical properties in the Expedition 403 methods chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026a]). Three measurements were made on the same interval, but we encountered a few failed measurements from the TK04 meter. Some cores did not have suitable intervals for thermal conductivity, especially in XCB cores, which often had small biscuiting, large clasts, and cracks on the surface of split core halves. Therefore, there may be some gaps in thermal conductivity data downcore. Thermal conductivity values display some oscillations between higher and lower values (e.g., ~1.6–1.1 W/[m·K] from ~250 to 275 mbsf and ~1.8–1.1 W/[m·K] from ~325 to 350 mbsf). Overall, thermal conductivity increases gradually from ~1.0 W/(m·K) at the seafloor to ~1.6 W/(m·K) at the base of Hole U1619A (Figure F23). This trend is consistent with an increase in sediment compaction downcore and agrees with the downcore decline in porosity observed in MAD samples.

6.7. Anelastic strain recovery

ASR experiments were conducted using a 10 cm sample from Section 403-U1619A-82X-6 (66–76 cm). After STMSL and NGR scanning, the core liner was cut on the core receiving platform (catwalk) and the sample was pushed out of the core liner. To attach 16 strain gauges, soft materials surrounding the core samples were removed and the surfaces were flattened. Gauges were glued onto the surfaces, wrapped with plastic bags, and put into a thermostatic water bath. Then, all the strain gauges were electrically connected to the data logger to collect 3D strain recovery. All sample preparation procedures were completed within 3–4 h after core recovery. Gauges remained connected to the samples to monitor strain value for ~14 days to fully record the recovery. Preliminary results show that after temperature equilibrium, strain released logarithmically but several channels suffered from shrinking, suggesting pore pressure changes due to continuous degassing (Figure F24). Postexpedition, inversion analysis will be conducted to convert the raw strain data set to 3D strain, which will be combined with azimuths of core samples by paleomagnetism to determine actual principal stress azimuths.

6.8. Physical properties summary

There is generally good correspondence between data collected at higher resolution on the MS loop sensor and data collected at lower resolution on the MSP sensor. The MSP measurements picked up additional peaks in MS that were missed during the averaging in WRMSL measurements. There is also good correspondence between GRA bulk density and discrete MAD sample measurements. Due to issues with gas, as discussed above, P-wave velocity data are not considered reliable, and there is no detectable signal in discrete nor logger data below ~20 mbsf. Thermal conductivity generally increases with depth, in agreement with a decline in sediment porosity.

A notable feature of Site U1619 is the prevalence of peaks with MS values that are orders of magnitude higher than the background. The outsized peaks are infrequent in the upper part of the record, appear at ~ 150 mbsf, and become more prominent below ~250 mbsf. These MS maxima are likely associated with authigenic iron sulfide nodules (see Paleomagnetism) similar to those observed at Site U1618 (see Physical properties in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b]) and likely indicate diagenetic alteration.

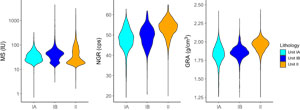

MS, NGR, and GRA density data by lithostratigraphic units (see Lithostratigraphy) are summarized in Figure F25. MS is generally low in Subunit IA, indicating this subunit lacks a strong postdepositional alteration signal. MS has two modes in Subunit IB and Unit II, where a lower mode may represent primary depositional processes and a higher mode may represent secondary postdepositional processes. The Subunit IB high MS mode is larger than the low MS mode. In contrast, the Unit II low MS mode is larger than the high MS mode, which is consistent with observed broad stratigraphic intervals of low MS (<50 IU) alternating with shorter stratigraphic intervals of large MS peaks. Higher NGR and GRA bulk density in Unit II, combined with both low and high MS modes, suggest that clay-rich (high NGR) compacted sediments (high GRA bulk density) are less likely to accommodate fluid movement, leading to greater retention of a primary magnetization (low MS) flanked by horizons associated with the formation of authigenic minerals (high MS). NGR and GRA bulk density are good markers of lithologic changes downcore. Subunit IA displays the highest variability in both parameters. Subunit IB has a tighter mode in GRA bulk density, whereas Unit II has overall higher NGR and GRA density values. Variability in these properties is likely associated with changes in clay content due to changes in sediment delivery and depositional processes across glacial–interglacial cycles. Further studies onshore are necessary to interpret the relationship between physical properties measured on board, depositional lithofacies, and postdepositional alteration.

7. Stratigraphic correlation

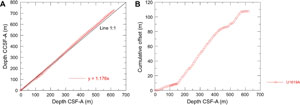

Only a single hole was occupied at Site U1619, and therefore no correlation was applied. The 85 cores reached a depth of 627.9 mbsf and were positioned in stratigraphic order relative to their advance and curated length when recovery was greater than 100%. This resulted in a total core composite depth below seafloor, Method A (CCSF-A), of 736.66 m (Figure F26; Table T7).

The offset between the CCSF-A and CSF-A depth scales is nearly linear (Figure F27A), but close inspection of the cumulative offset as a function of depth (mbsf) (Figure F27B) shows relatively low growth rate in the upper part of the hole (0 to ~150 mbsf). The recovery below ~150 mbsf is strongly affected by gas expansion, leading to growth rates of ~1.18. In general, recovery for Hole U1619A was very good and often >100%. We appended subsequent cores by their expansion, assuming minimal coring gaps between cores except for several cores with <100% recovery.

In summary, despite being a site with a single hole, the very good recovery and minimal gaps provide a good record for long-term reconstructions. Calculation of mass accumulation rates based on the CCSF scale should account for the expansion by dividing apparent depth intervals by the appropriate growth factor.

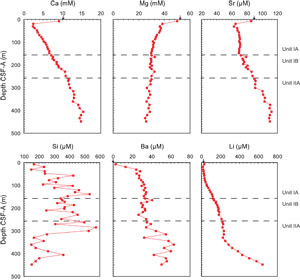

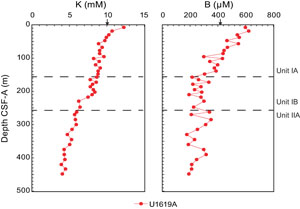

8. Geochemistry

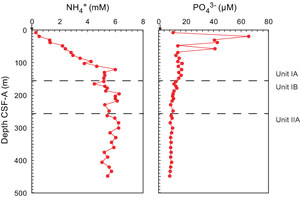

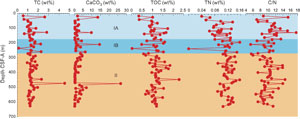

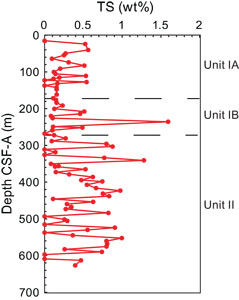

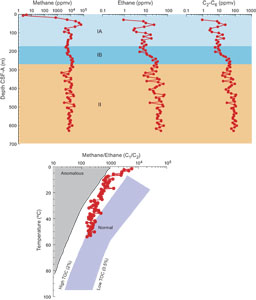

Samples for IW chemistry, bulk sediment geochemistry, and headspace gas were analyzed at Site U1619. The main findings from IW analysis are reflective of the gas hydrate and free gas system, fluid flow, and diagenetic reactions. Additionally, a few measured analytes in the IWs appear to correlate with changes in lithostratigraphic units. There are some high peaks of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), possibly derived from authigenic carbonate, and total organic carbon (TOC)/total nitrogen (TN) (C/N) ratios indicate that the organic matter is primarily of marine algae origin. Methane concentrations peaked sharply at 57 mbsf, due to microbial methanogenesis, and ethane and heavier hydrocarbons (C2–C6) indicated nonbiological diagenesis with increasing depth.

8.1. Interstitial water chemistry

A total of 41 IW samples were squeezed from 5 or 10 cm whole-round samples, yielding 10 cm3 of water for subsequent analysis. Major and trace elements, as well as anions and cations (Table T8), were measured following established International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) geochemistry methods (see Geochemistry in the Expedition 403 methods chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026a]).

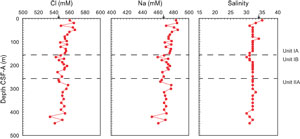

8.1.1. pH, chloride, sodium, and salinity

pH was measured and maintained a value of ~8, similar to Site U1618, with the exception of an inflection at 110.14 mbsf, where a pH value of 4 was recorded. Conservative tracers of chloride (Cl), sodium (Na), and salinity can be useful indicators of gas hydrate dissociation and formation within sediments, where gas hydrate dissociation is a process by which hydrates are broken down within the sediments, resulting in freshening of IWs within the sediment column (e.g., Ussler and Paull, 2001; Kastner et al., 2008). The Cl and Na concentrations show variability with depth; however, the general trend of these conservative tracers is decreasing slightly with depth. Chloride concentrations decrease from ~560 mM at 7.7 mbsf to ~541 mM at 448.35 mbsf. Sodium concentrations measured via ion chromatography (IC) decrease from ~483 mM at 7.7 mbsf to ~458 mM at 448.35 mbsf. Although Na was measured via both inductively coupled plasma (ICP) spectroscopy and IC, the mean of both analysis types is equivalent (~471 mM). Additionally, there is small variability in the salinity data, and decreases from 35 at 7.7 mbsf to 31 at 448.35 mbsf. The two minimum salinity concentrations are located at 164.65 and 404.82 mbsf, where salinity reaches a value of 30. The geochemistry profiles of Cl, Na, and salinity (Figure F28) are likely reflective of slight freshening of the IWs, possibly indicating some gas hydrate and free gas processes at depth.

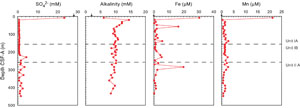

8.1.2. Sulfate, alkalinity, iron, and manganese

The depth of the sulfate–methane transition zone (SMTZ) is a qualitative proxy for the upward flux of methane, where a shallow (near the sediment/water interface) SMTZ occurs in locations with high methane supply (Borowski et al., 1996; Graves et al., 2017). The SMTZ is characterized by the onset of methane increase in the headspace combined with sulfate depletion in the pore waters. Sulfate at Site U1619 is rapidly depleted from ~23 mM at 7.7 mbsf to ~0.6 mM at 18.69 mbsf, where sulfate remains at values ≤ 1 mM to 209.81 mbsf. Sulfate concentrations deeper than 209.81 mbsf range between 1 and 4 mM.

The rapid depletion of sulfate in the IWs between 7.7 and 18.69 mbsf corresponds to an increase in methane in the headspace samples (see Headspace gas geochemistry), suggesting the SMTZ at Site U1619 is shallow and likely located between 7.7 and 18.69 mbsf. Additionally, the alkalinity data support the shallow SMTZ interpretation. Alkalinity increases from ~6 mM at 7.7 mbsf to ~14 mM at 18.69 mbsf, which is consistent with bicarbonate production occurring within the SMTZ likely due to anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM).