Lucchi, R.G., St. John, K.E.K., Ronge, T.A., and the Expedition 403 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 403

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.403.106.2026

Sites U1621–U16231

![]() R.G. Lucchi,

R.G. Lucchi,

![]() K.E.K. St. John,

K.E.K. St. John,

![]() T.A. Ronge,

T.A. Ronge,

![]() M.A. Barcena,

M.A. Barcena,

![]() S. De Schepper,

S. De Schepper,

![]() L.C. Duxbury,

L.C. Duxbury,

![]() A.C. Gebhardt,

A.C. Gebhardt,

![]() A. Gonzalez-Lanchas,

A. Gonzalez-Lanchas,

![]() G. Goss,

G. Goss,

![]() N.M. Greco,

N.M. Greco,

![]() J. Gruetzner,

J. Gruetzner,

![]() L. Haygood,

L. Haygood,

![]() K. Husum,

K. Husum,

![]() M. Iizuka,

M. Iizuka,

![]() A.K.I.U. Kapuge,

A.K.I.U. Kapuge,

![]() A.R. Lam,

A.R. Lam,

![]() O. Libman-Roshal,

O. Libman-Roshal,

![]() Y. Liu,

Y. Liu,

![]() L.R. Monito,

L.R. Monito,

![]() B.T. Reilly,

B.T. Reilly,

![]() Y. Rosenthal,

Y. Rosenthal,

![]() Y. Sakai,

Y. Sakai,

![]() A.V. Sijinkumar,

A.V. Sijinkumar,

![]() Y. Suganuma, and

Y. Suganuma, and

![]() Y. Zhong2

Y. Zhong2

1 Lucchi, R.G., St. John, K.E.K., Ronge, T.A., Barcena, M.A., De Schepper, S., Duxbury, L.C., Gebhardt, A.C., Gonzalez-Lanchas, A., Goss, G., Greco, N.M., Gruetzner, J., Haygood, L., Husum, K., Iizuka, M., Kapuge, A.K.I.U., Lam, A.R., Libman-Roshal, O., Liu, Y., Monito, L.R., Reilly, B.T., Rosenthal, Y., Sakai, Y., Sijinkumar, A.V., Suganuma, Y., and Zhong, Y., 2026. Sites U1621–U1623. In Lucchi, R.G., St. John, K.E.K., Ronge, T.A., and the Expedition 403 Scientists, Eastern Fram Strait Paleo-Archive. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 403: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.403.106.2026

2 Expedition 403 Scientists’ affiliations.

1. Background and objectives

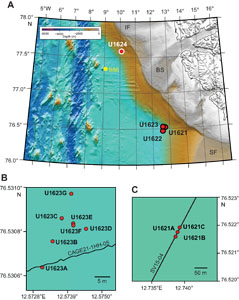

The Bellsund drift coring sites are located on a plastered sediment drift that developed along the lower continental slope (1700–1800 m water depth) of the western margin of Svalbard under the influence of the northward-flowing West Spitsbergen Current (WSC) (Rebesco et al., 2013) (Figure F1). The Bellsund drift has built up over millions of years since the opening of the Fram Strait (17–10 Ma) (Jakobsson et al., 2007; Engen et al., 2008; Ehlers and Jokat, 2013), which determined the onset of the contour current circulation system in the area (Eiken and Hinz, 1993; Gebhardt et al., 2014), with development of sediment drifts covering large areas of the European North Atlantic margin, including the Norwegian Sea, Barents Sea, the western margin of Svalbard, and along the eastern side of the Fram Strait (Laberg et al., 2005). Sediment drifts are depocenters developing under persistent bottom currents (Stow et al., 2002; Rebesco, 2014b) that substantially rework the sediments delivered to the marine environment through terrestrial and marine processes. The bottom currents transport sediments, oxygen, and nutrients along the margin, making the environment ideal for biological productivity with sediments rich in carbonate biogenic fraction if postmortem diagenetic conditions allow for their preservation. The Bellsund drift recorded the continental input associated with the expansion and retreat of the paleo-Svalbard–Barents Sea Ice Sheet (SBSIS) during the past glacial and interglacial cycles (glacial debris flows and sediment-laden meltwater plumes) and the variability of the warm WSC through its effect on the marine biological productivity in the water column (Lucchi et al., 2018; Caricchi et al., 2019; Torricella et al., 2022, 2025; Gamboa Sojo et al., 2024). Its location between the Storfjorden Trough Mouth Fan (TMF) to the south and the Bellsund TMF to the north provided some protection from direct glacigenic input from the paleo-SBSIS during the past glaciations while still capturing a record of the ice sheet dynamics.

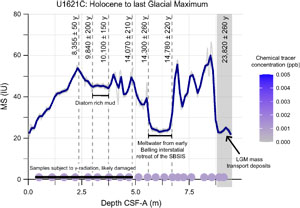

Piston core work in this area demonstrates that the Bellsund drift is an excellent setting to recover continuous, expanded, and datable sedimentary sequences for detailed paleoclimatic and paleoceanographic analyses. The 2014 Eurofleets2-PREPARED project (Lucchi et al., 2014) recovered a long Calypso piston core from the Bellsund drift that contains a continuous, very expanded paleoclimatic record spanning the last 40 ky with up to subcentennial resolution. A robust age model was defined through paleomagnetic and biostratigraphic analyses, the identification of tephras, and radiocarbon dating of the abundant biogenic carbonate fraction (Caricchi et al., 2019, 2020). The sedimentologic analyses indicate the consistent presence of contouritic deposition and the existence of short-lived, abrupt depositional events associated with prominent meltwater events, including the MWP-1A (Lucchi et al., 2013, 2015); the MWP-1A0 (Caricchi et al., 2019), also known as MWP-19ka (Yokoyama et al., 2000, Clark et al., 2004); and Heinrich-like events indicating a highly dynamic paleo-SBSIS during the last 60 ky (Lucchi et al., 2018; Caricchi et al., 2019).

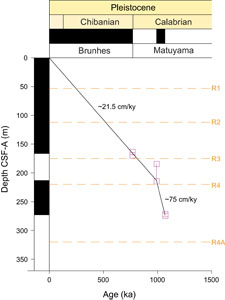

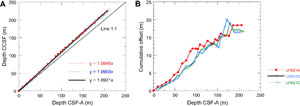

The drill sites on the Bellsund drift (Sites U1621 and U1623) are designed to recover an expanded sedimentary sequence to specifically examine suborbital oscillations of the last 100 ky, the mid-Brunhes event (~400 ka), the mid-Pleistocene transition (~1.2–0.7 Ma), and the primary establishment of shelf edge-glaciation in this area at about 1.3 Ma corresponding to Seismic Reflector R4A (Rebesco et al., 2014a). Site U1621 (Figure F2A) was chosen because seismic profiles indicate a highly expanded sediment record down to Seismic Reflector R3 (~0.75 Ma), with sedimentation rates potentially exceeding 300 m/My. Three holes were drilled at Site U1621 (Figure F1C) down to Seismic Reflector R3 (~225 meters below seafloor [mbsf]) with a maximum penetration depth of 216 mbsf. Because of a discrepancy in coordinate transcription, Site U1622 was drilled into the Storfjorden TMF (~8 km from the intended site) to 46.5 mbsf (Figure F2B). Site U1623 was located ~4.4 km downslope from Site U1621 (Figure F2A) to drill a longer record down to Seismic Reflector R4A (~1.3 Ma; ~347 mbsf). Seven holes were drilled at Site U1623 (Figure F1B) with a maximum drilled depth of 370 mbsf. Water depths at all three sites were between 1636 and 1715 m.

The research objectives for these sites include the following:

- Reconstruction of a high-resolution sediment stratigraphy since the onset of Pleistocene shelf-edge glaciation;

- Study of ocean-cryosphere interactions and forcing mechanisms on the paleo–ice sheet dynamics; and

- Investigation of the influence of the WSC variability through time on the ice coverage, climate, and microbial populations and to what extent this is still affecting contemporary geochemical fluxes.

2. Operations

In total, we spent 4.27 days at Site U1621 and penetrated a maximum depth of 216.1 mbsf with a combined penetration of 639.3 m. The cored interval of 517.3 m resulted in a recovered length of 464.62 m. Site U1621 consists of three holes that stretch across a 40 m interval (20 m between holes). Hole U1621A is located on Seismic Line SV15-04, and the other holes were offset at a bearing of 22° along the seismic line. We took 89 cores in total: 45% with the advanced piston corer (APC) system (40 cores), 24% with the half-length APC (HLAPC) system (21 cores), and 31% with the extended core barrel (XCB) system (28 cores).

At Site U1622, we spent 0.54 days in total and penetrated to a maximum depth of 46.5 mbsf. The cored interval of 46.5 m resulted in a recovered length of 46.26 m. Site U1622 consists of only one hole. During coring operations, it was discovered that the coordinates for proposed Site BED-02B (Lucchi et al., 2023) were not the coordinates of the approved shot point for the site. Upon discovery, coring was terminated, the correct coordinates were calculated, and the vessel departed for Site U1623 (proposed Site BED-02B). We took seven cores in total at Site U1622: 86% with the APC system (6 cores) and 14% with the HLAPC system (1 core).

In total, we spent 10.3 days at Site U1623 and penetrated to a maximum depth of 370 mbsf with a combined penetration of 1422.4 m. The cored interval of 1422.4 m resulted in a recovered length of 1314.38 m. Site U1623 consists of seven holes. Hole U1623A is located on Seismic Line CAGE21-1HH-05. Holes U1623B, U1623C, and U1623G stretch along a 60 m long transect from Hole U1623A at a bearing of 22°. Holes U1623C and U1623D are 20 m apart at a bearing of 110°, with Holes U1623E and U1623F in the middle between Holes U1623C and U1623D. Holes U1623B and U1623E did not recover a good mudline; thus, coring was abandoned after one core. It was determined that Hole U1623F sidetracked into an adjacent hole; thus, coring was terminated after Core 22F. We took 205 cores in total: 29% with the APC system (58 cores), 30% with the HLAPC system (62 cores), and 41% with the XCB system (85 cores).

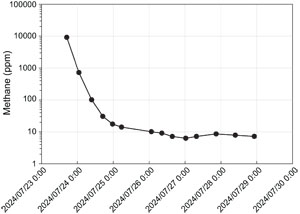

To minimize magnetic overprinting on the cored sediment, nonmagnetic collars and core barrels were used for all APC and HLAPC coring at Sites U1621–U1623. Most holes had intervals where the sediments expanded due to the presence of gas, resulting in recoveries sometimes exceeding 100% as well as intervals of poor recovery due to the presence of clast-rich glacial deposits (Tables T1, T2, T3). To mitigate the impact of expansion and the potential for core disturbance and to release the pressure, holes were drilled into the liner by the drill crew on the rig floor and the technical staff on the core receiving platform. In addition, some XCB cores were advanced by 8 m to allow for gas expansion of the sediments in the liners. Initially, downhole logging was attempted in Hole U1623C with the triple combination (triple combo) and Formation MicroScanner (FMS)-sonic tool strings. However, because an obstruction made it impossible for the logging tools to exit the bottom-hole assembly (BHA), logging was terminated in Hole U1623C. A second downhole logging attempt was successfully completed in Hole U1623D.

To more easily communicate shipboard results, core depth below seafloor, Method A (CSF-A), depths in this chapter are reported as mbsf unless otherwise noted.

2.1. Site U1621

2.1.1. Hole U1621A

The vessel completed the 138.0 nmi transit from Site U1620 in 11.5 h at an average speed of 12.0 kt. Thrusters were down and secure and the vessel in full automatic dynamic positioning (DP) mode at 0743 h local time (UTC + 2 h) on 7 July 2024, beginning operations at Site U1621. Site U1621 was initially planned for two cored holes, both to the approved depth of 397.0 mbsf. Three holes were eventually cored. However, a gravel layer caused coring to be terminated prior to the approved depth in all three holes. An APC/XCB BHA was assembled, and Hole U1621A was spudded at 1320 h. The seafloor depth was calculated to be 1638.6 meters below sea level (mbsl) based on recovery from Core 1H. Coring continued with the APC system to 86.3 mbsf (Cores 1H–10H). Because of gas expansion in the cores, it was decided to switch to the XCB system and use advances of 8.0 m to allow for expansion of the sediments in the liners. The XCB system was used to core from 86.3 to 108.8 mbsf (Cores 11X–14X), and coring was switched back to the APC system due to poor recovery. The APC system was then used to 139.8 mbsf (Cores 15H–18H). Partial strokes were noted on Cores 16H–18H, and a broken liner was noted on Core 17H. Coring was switched to the HLAPC system to advance the hole to 157.1 mbsf (Cores 19F–22F). Partial strokes were recorded on Cores 21F and 22F; therefore, these were advanced by recovery and ended HLAPC coring. Hole U1621A was advanced to its total depth of 215.3 mbsf using the XCB system (Cores 23X–28X). The rate of penetration slowed, and recovery was low for the final two cores. It appeared that the bit had reached a gravel layer. Coring was terminated after Core 28X, and the bit was pulled out of the hole, clearing the seafloor at 1745 h on 8 July and ending Hole U1621A.

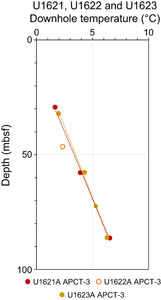

A total of 28 cores were taken over a 215.3 m interval with 180.40 m of recovery (84%) (Table T1). The APC system was used for a total of 14 cores over a 117.3 m interval with 124.78 m of recovery (106%). The HLAPC system was used for 4 cores over a 17.3 m interval with 18.06 m of recovery (104%). The XCB system took 10 cores over an 80.7 m interval with 37.56 m of recovery (47%). The advanced piston corer temperature (APCT-3) tool was deployed on Cores 4H, 7H, and 10H. Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores.

2.1.2. Hole U1621B

The vessel was offset 20 m at a bearing of 22°, and Hole U1621B was spudded at 2038 h on 8 July 2024. The seafloor depth was calculated to be 1636.5 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. Coring continued with the APC and HLAPC systems to 139.9 mbsf (Cores 1H–20F), when the XCB system was used to adjust for correlation purposes on Core 21X for an advance of 2.5 m. The HLAPC system was then deployed for Core 22F, for which a partial stroke was recorded. The XCB system was again used for Cores 23X–33X to advance the hole to its total depth of 216.1 mbsf, where the same gravel layer was encountered and coring was terminated. The bit was pulled out of the hole, clearing the seafloor at 0812 h on 10 July and ending Hole U1621B.

A total of 33 cores were taken over a 216.1 m interval, recovering 203.39 m of sediment (94%) (Table T1). The APC system was deployed for 10 cores over a 92.9 m interval with 98.16 m of recovery (106%); the HLAPC system was deployed for 11 cores over a 51.7 m interval with 55.23 m of recovery (107%); and the XCB system was deployed for 12 cores over a 71.5 m interval, recovering 50.00 m of sediment (70%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC cores. Total time spent on Hole U1621B was 38.50 h (1.6 days).

2.1.3. Hole U1621C

The vessel was offset 20 m at 22° from Hole U1621B, and Hole U1621C was spudded at 1012 h on 10 July 2024. The seafloor was calculated to be 1635.9 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. The HLAPC system was deployed for Core 2F to support sediment recovery for microbiology sampling in the hole, after which APC coring continued to 147.9 mbsf (Cores 3H–17H), where partial strokes on Cores 16H and 17H signaled APC refusal. The HLAPC system was then redeployed and advanced the hole to 171.4 mbsf. The XCB system was deployed to advance the hole to its total depth of 207.9 mbsf (Cores 23X–28X), where the same gravel layer was encountered and coring was terminated. The bit was pulled out of the hole, clearing the seafloor at 1415 h on 11 July and ending Hole U1621C, and the vessel began a 4.6 nmi DP transit to Site U1622.

A total of 28 cores were taken over a 207.9 m interval, recovering 195.18 m of sediment (94%) (Table T1). The APC system was deployed for 16 cores over a 143.2 m interval with 148.5 m of recovery (104%); the HLAPC system was deployed for 6 cores over a 28.2 m interval with 30.90 m of recovery (110%); and the XCB system was deployed for 6 cores over a 36.5 m interval, recovering 15.83 m of sediment (43%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores. A total of 30 h (1.3 days) were spent on Hole U1621C.

2.2. Site U1622

2.2.1. Hole U1622A

The vessel made the 4.6 nmi transit from Site U1621 to Site U1622 in DP mode, beginning the transit when the bit cleared the seafloor at Hole U1621C. The bit was pulled to the rig floor during the transit and changed for an APC roller-cone bit. The bit was deployed to depth while in transit and was ready upon arrival. The vessel arrived on site at 0012 h on 12 July 2024. Hole U1622A was spudded at 0244 h on 12 July. The seafloor was calculated to be 1707.5 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. APC coring continued to 41.8 mbsf. A gravel layer was encountered almost immediately, causing partial strokes on Cores 4H–6H. The HLAPC system was then deployed for Core 7F to 46.5 mbsf. At this time, it was determined that the coordinates in Lucchi et al. (2023) did not agree with the shotpoint listed as a reference. Calculations were done, and new coordinates were determined. The bit was pulled out of the hole to three stands above seafloor. The bit cleared the seafloor at 1305 h, and the vessel was underway to the coordinates for Site U1623 at 1312 h on 12 July, ending Hole U1622A.

A total of seven cores were taken over a 46.5 m interval, recovering 46.26 m of sediment (99%) (Table T2). The APC system was deployed for six cores over a 41.8 m interval with 41.15 m of recovery (98%), and the HLAPC system was deployed for one core over a 4.7 m interval with 5.11 m of recovery (109%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores. Total time spent on Hole U1622A was 13.0 h (0.5 days).

2.3. Site U1623

2.3.1. Hole U1623A

The vessel began the 4.4 nmi move from Site U1622 to Site U1623 in DP mode when the bit cleared the seafloor at 1315 h on 12 July 2024 and arrived on location at 1800 h on the same day, making the transit in 4.4 h with an average speed of 0.92 kt.

The bit was lowered to the seafloor, and Hole U1623A was spudded at 1920 h on 12 July. The seafloor depth was calculated to be 1707.5 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. Coring continued with the APC system to 58.2 mbsf (Cores 1H–8H). Core 8H was a partial stroke with 0.43 m of recovery, and it was decided to attempt a HLAPC core to determine if the formation had changed or if a stiff layer was encountered. Core 9F was a full stroke, and another APC core was tried for Core 10H. This resulted in a partial stroke, and it was decided to continue to advance the hole using the HLAPC system. The HLAPC system was deployed from 72.1 to 142.6 mbsf (Cores 11F to 25F), where two partial strokes determined HLAPC refusal. The XCB system was then deployed to extend the hole from 146.2 mbsf to a final depth of 369.3 mbsf with Core 51X at 2200 h on 14 July. The bit pulled out of the hole, clearing the seafloor at 0011 h on 5 July and ending Hole U1623A.

A total of 51 cores were taken over a 369.3 m interval, recovering 330.72 m of sediment (90%) (Table T3). The APC system was deployed for 9 cores over a 67.4 m interval with 67.65 m of recovery (100%); the HLAPC system was deployed for 16 cores over a 75.2 m interval with 78.71 m of recovery (105%); and the XCB system was deployed for 51 cores over a 226.7 m interval, recovering 184.36 m of sediment (81%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores. Total time on Hole U1623A was 54.25 h (2.3 days).

2.3.2. Hole U1623B

The vessel was offset 20 m at a bearing of 22°, and the drill string was flooded with perfluorocarbon tracer (PFT) for microbiology sampling on the hole. Hole U1623B was spudded at 0238 h on 15 July 2024 with Core 1H, recovering 0.05 m of rock and gravel. Hole U1623B was terminated at 0300 h in favor of achieving a better mudline. Total time on Hole U1623B was 2.75 h (0.1 days) (Table T3).

2.3.3. Hole U1623C

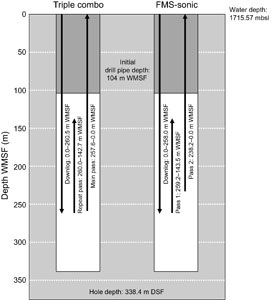

The vessel was offset 20 m at a bearing of 22°, and the drill string was flooded with PFT for microbiology sampling on the hole. Hole U1623C was spudded at 0320 h on 15 July 2024. The seafloor was estimated to be 1706.4 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. APC coring continued to 79.9 mbsf (Cores 1H–9H). Partial strokes on Cores 8H and 9H signaled APC refusal. The HLAPC system was then deployed to extend the hole to 163.4 mbsf (Cores 10F–28F), and the XCB system was deployed for a 7 m interval (Core 18X) for correlation purposes. Partial strokes on Cores 27F and 28F signaled HLAPC refusal. The XCB system was deployed to extend the hole to its final depth of 369.0 mbsf (Cores 29X–55X) at 0545 h on 17 July. The hole was then prepared for logging by pumping a 70 bbl sweep of sepiolite mud, and the bit was pulled to a logging depth of 65.5 mbsf. The Schlumberger equipment was rigged up, and the triple combo tool string was assembled and deployed. The tool string tagged an obstruction in the drill pipe approximately 80 m prior to exiting the bit. Efforts to pass the obstruction were unsuccessful, and the tool string was pulled to the surface. The top drive was picked up, moving the bit by about 2 m, and connected to the drill pipe, and the driller pressured up the drill string to approximately 1800 psi to clear the obstruction. Once the pressure returned to normal, a deplugger was deployed to verify that the drill string was clear. The bit was again placed at 65.5 mbsf, and the triple combo tool string was again deployed. The tool string encountered an obstruction as it was exiting the bit and was unable to pass. Logging was terminated, and the tool string was recovered and rigged down. The bit was recovered, clearing the seafloor at 1830 h and the rig floor at 2050 h on 17 July. The rig floor was secured for transit, and the vessel switched from DP to cruise mode at 2319 h on 17 July, ending Hole U1623C.

A total of 55 cores were taken over a 369 m interval, recovering 322.38 m of sediment (87%) (Table T3). The APC system was deployed for 9 cores over a 79.9 m interval with 73.68 m of recovery (93%); the HLAPC system was deployed for 18 cores over a 76.5 m interval with 75.90 m of recovery (99%); and the XCB system was deployed for 28 cores over a 212.6 m interval, recovering 172.8 m of sediment (91%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores. Total time on Hole U1623C was 65.5 h (2.9 days). At this point, coring operations shifted to Site U1624.

2.3.4. Hole U1623D

Following coring operations at Site U1624, the decision was made to return to Site U1623 for additional coring and to reattempt logging at a new hole. The vessel was moved to coordinates that located it 20 m southeast of Hole U1623C, and an APC/XCB BHA was assembled and deployed. Hole U1623D was spudded at 0108 h on 22 July 2024. The seafloor was calculated to be 1715.6 mbsl based on recovery in Core 1H. Coring continued with the APC coring system to 103.9 mbsf (Cores 1H–13H). The HLAPC system was used once in this interval (Core 3F) for correlation purposes. There were partial strokes on Cores 6H, 10H, and 13H. The HLAPC system was then used to extend the hole to 156.4 mbsf (Cores 14F–25F). Partial strokes were recorded on Cores 17F, 23F, and 25F. The XCB coring system was then deployed to extend the hole to the total depth of 370 mbsf at Core 56X. On 23 July, XCB coring was paused for 1.5 h while the core winch depth indicator was repaired; the downtime occurred between Cores 34X and 35X.

After coring was completed on 24 July, the hole was conditioned for logging and the bit was pulled to a logging depth of 98.4 mbsf. The triple combo logging tool string was rigged up and deployed at 1230 h on 24 July. The tools reached 249.8 mbsf and began logging from that point. The triple combo run was completed, and the tools were recovered. The FMS-sonic tool string was rigged up and deployed at 1800 h on 24 July. The first pass of the FMS-sonic string reached 249.8 mbsf, but the second pass was only able to reach 227.8 mbsf before tagging an obstruction. The logging runs were completed, and the tools were recovered at 2200 h. The bit was then pulled out of the hole, clearing the seafloor at 2331 h on 24 July and ending Hole U1623D.

A total of 56 cores were taken over a 370 m interval, recovering 351.06 m of sediment (95%) (Table T3). The APC system was deployed for 12 cores over a 99.2 m interval with 100.62 m of recovery (101%); the HLAPC system was deployed for 13 cores over a 57.2 m interval with 60.94 m of recovery (107%); and the XCB system was deployed for 31 cores over a 213.6 m interval, recovering 189.50 m of sediment (89%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores. The total time on Hole U1623D was 76.75 h (3.2 days).

2.3.5. Hole U1623E

The vessel was offset 10 m at a bearing of 292° from Hole U1623D, locating it approximately halfway between Holes U1623C and U1623D. Hole U1623E was spudded at 0238 h on 25 July 2024, with Core 1H recovering 9.6 m of core. The seafloor was calculated to be 1707.2 mbsl. However, with a full core barrel, it was decided to abandon the hole in favor of obtaining a better mudline core. The hole was ended at 0300 h on 25 July. Total time on Hole U1623E was 3.50 h (0.1 days) (Table T3).

2.3.6. Hole U1623F

The vessel was offset 1.5 m at a bearing of 180°, and Hole U1623F was spudded at 0323 h. The seafloor depth was calculated to be 1706.8 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. APC coring continued to 120.0 mbsf (Cores 1H–13H). There was poor recovery on Cores 11H–13H, and it was decided to use the HLAPC system to advance the hole in an attempt to increase recovery. The HLAPC system was deployed for Cores 14F–22F to 162.3 mbsf. Cores 11H–22F were very unconsolidated, and no weight on bit was required to drill ahead after coring. It was concluded that the bit sidetracked into an adjacent hole. Thus, for most sampling requirements, Cores 11H–22F should be avoided. Coring in Hole U1623F was terminated, and the bit was pulled to the surface, clearing the seafloor at 2105 h on 25 July 2024 and ending Hole U1623F.

A total of 22 cores were taken over a 162.3 m interval, recovering 147.04 m of sediment (86%) (Table T3). The APC system was deployed for 13 cores over a 120 m interval with 103.47 m of recovery (86%), and the HLAPC system was deployed for 9 cores over a 42.3 m interval with 43.57 m of recovery (103%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores. Total time on Hole U1623F was 18.00 h (0.75 days).

2.3.7. Hole U1623G

It was decided to offset 20 m at a bearing of 22° from Hole U1623C. The vessel was in position at 2130 h on 25 July 2024, and Hole U1623G was spudded at 2245 h. The seafloor depth was calculated to be 1704.9 mbsl based on recovery from Core 1H. APC coring continued to 113.9 mbsf (Cores 1H–13H). Partial strokes were recorded on Cores 8H, 10H, and 13H. The HLAPC system was deployed to the total depth of 142.1 mbsf (Cores 14F–19F). Under the applause of all JOIDES Resolution Science Operator (JRSO) staff and scientists, the final core of Expedition 403 and the last core of JOIDES Resolution under JRSO was on deck at 1220 h. The bit was pulled to the surface, clearing the seafloor at 1500 h and the rig floor at 2015 h. The rig floor was secured for transit, and the vessel switched from DP to cruise mode at 2036 h, ending Hole U1623G and Site U1623.

A total of 19 cores were taken over a 142.1 m interval, recovering 153.50 m of sediment (108%) (Table T3). The APC system was deployed for 13 cores over a 113.9 m interval with 123.16 m of recovery (108%), and the HLAPC system was deployed for 6 cores over a 28.2 m interval with 30.34 m of recovery (108%). Nonmagnetic core barrels were used on all APC and HLAPC cores. Total time on Hole U1623G was 23.50 h (1.0 days).

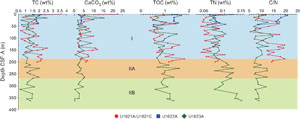

3. Lithostratigraphy

This lithostratigraphic summary characterizes Sites U1621–U1623, which are located with a distance between sites of 8.6 km (Sites U1621 and U1622), 8.2 km (Sites U1622 and U1623), and 4.4 km (Sites U1621 and U1623). Sites U1621 and U1623 were drilled into the same drift body along Seismic Lines SV15-04 and CAGE21-1HH-05, respectively, and at different relative distances to the adjacent Storfjorden TMF characterized by frequent occurrence of mass transport deposits (MTDs) (Figure F2). Site U1622 was located slightly off Seismic Line CAGE21-1HH-03 (Figure F2B) and penetrated a thick sequence of MTDs of the northwestern fringes of the Storfjorden TMF. The sediments recovered at all three sites yielded comparable lithologies. Because the chapter outlines the lithologies of three different sites, common and discriminating features are discussed here prior to characterizing the units and subunits.

The recovered sequence at Site U1621 consists of 89 cores in a total of three holes with 639.3 m of sediment cored and 578.97 m recovered. At Site U1622, only one hole was drilled, and seven cores with a total cored length of 46.5 m and recovered length of 46.26 m were retrieved. The sequence at Site U1623 consists of 205 cores from a total of seven holes, with a total cored length of 1422.4 m and a recovery of 1314.38 m. In Hole U1623B, only 0.05 m of sediment was retrieved in the first core for the mudline, which was considered insufficient for continued coring, whereas Hole U1623E recovered 9.63 m in the first core over 9.6 m of core length, which did not allow for identification of the mudline. Hence, Hole U1623E was abandoned, and another mudline detection was performed on the adjacent Hole U1623F.

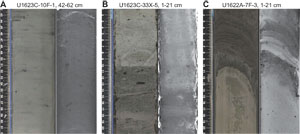

Sediments throughout all Sites U1621–U1623 holes are mainly siliciclastic, primarily composed of (dark) gray to greenish gray silty clay (Figure F3A, F3B), with coarser intervals containing reddish gray to dark reddish gray sandy mud (Figure F3C). The lithologies contain varying amounts of detrital clasts < 2 cm, and some single large clasts > 2 cm were identified from visual core descriptions and X-radiographs (Figure F4A, F4B). Clast abundance ranges from none to dispersed (<1% of the split core surface) to common (1%–5%) to abundant (5%–30%). When clast abundance is between 1% and 30% and clasts > 2 cm are observed on the split core surface, the lithology is designated as a diamicton (Figure F4C). Small intervals of diamicton (<2 m thickness) were observed in different cores and sites, with a major change to thicker diamictic layers below ~170–190 mbsf at Site U1621 and below ~300 mbsf at Site U1623.

The uppermost ~190 m of Sites U1621 and U1623 are characterized by the occurrence of sand patches (<5 mm) of predominantly white color (10YR 8/1) (Figure F5A). The same depth range also contains intervals of interbedded layers of mostly gray silty clay with white (10YR 8/1) silt that are either thinly (<0.3 cm) or thickly (0.3–1 cm) laminated (Figure F5B).

Between ~180 and 270 mbsf at Site U1623, bioturbation is distinctly stronger than above or below that depth range, mostly varying between heavy and complete (Figure F5C). Clasts also vary from absent to abundant.

Below ~270 mbsf at Site U1623, most intervals show no apparent bioturbation or they are slightly to moderately bioturbated. Clast occurrence increases downhole toward ~300 mbsf, where silty clay matrix with abundant clasts transitions into diamicton for a thickness of ~40 m. Below ~340 mbsf, silty clays with dispersed to common clasts form the deepest part of the drilled sequence in Holes U1623A and U1623C, whereas in Hole U1623D, diamicton was encountered below ~360 mbsf.

In contrast to Sites U1618–U1620, diagenetic overprint plays only a minor role in the sediments of Sites U1621–U1623. Only small iron sulfide minerals and sparse patches of authigenic carbonates are observed on the split core surface in the deeper part of the stratigraphic sequences.

The degree of core recovery, coring disturbance, and gas expansion differs between sites and varies with depth and type of coring method employed. APC sediment from all holes exhibits slight to moderate coring disturbances, whereas most XCB cores are slightly to moderately disturbed with the finer grained intervals being more affected than intervals with coarser material.

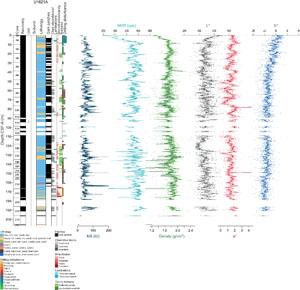

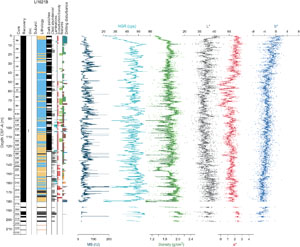

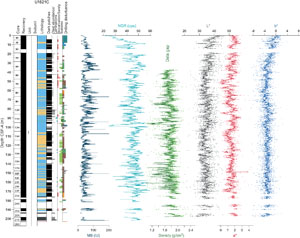

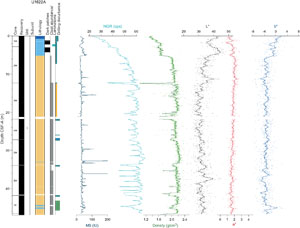

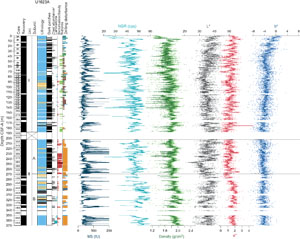

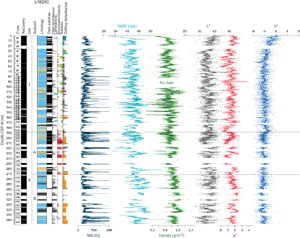

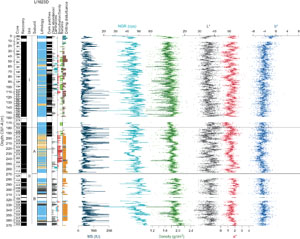

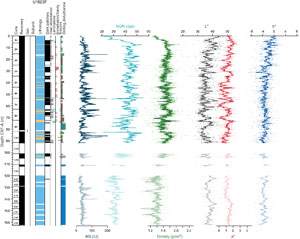

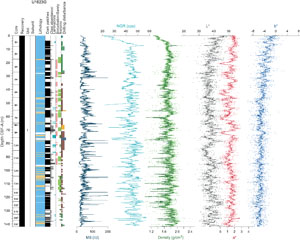

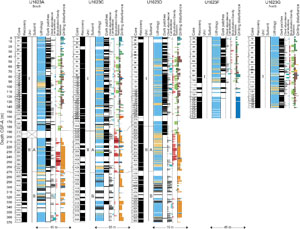

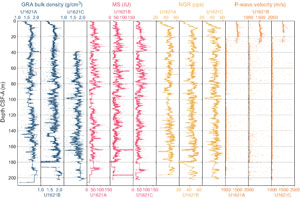

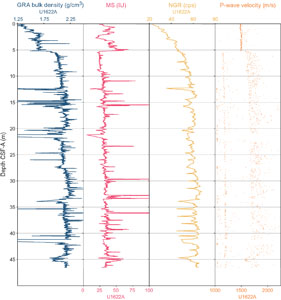

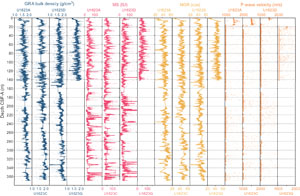

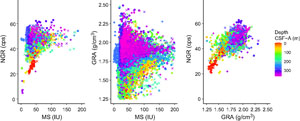

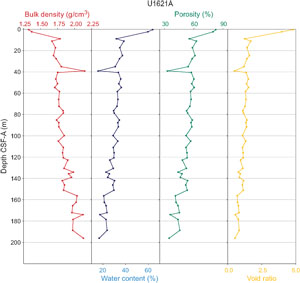

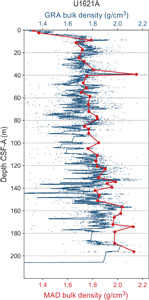

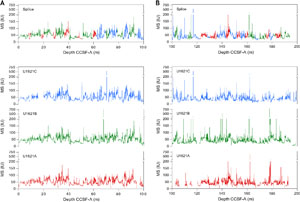

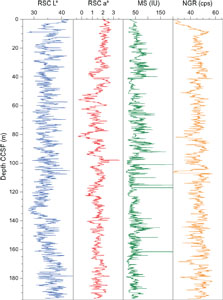

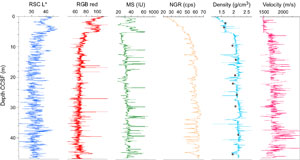

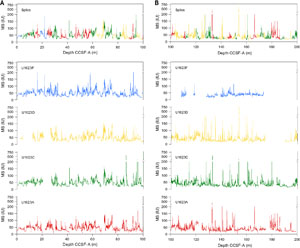

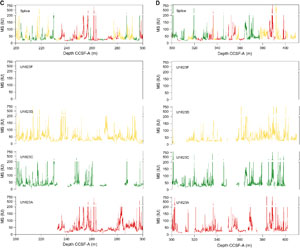

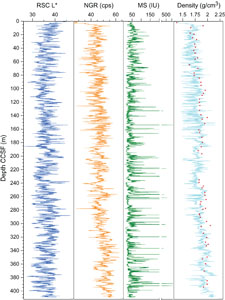

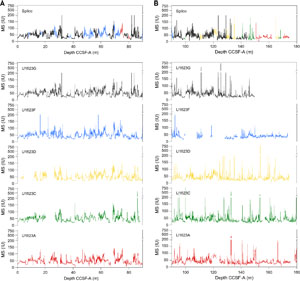

Sedimentary structures are not always visible on the split core surface (i.e., described as structureless), but primary (e.g., lamination) and secondary (e.g., iron sulfide minerals) structures are often observed in the X-radiographs. The sedimentologic characteristics of Site U1621 (Holes U1621A–U1621C) are summarized in Figures F6, F7, and F8; Site U1622 (Hole U1622A) in Figure F9; and Site U1623 (Holes U1623A, U1623C, U1623D, U1623F, and U1623G) in Figures F10, F11, F12, F13, and F14. These figures include information on core recovery; lithology as inferred from observations of the split core surfaces, X-radiographs, and smear slides; clast abundance; occurrence of sand patches and interbedded silty clay/silt layers; laminations; bioturbation; and drilling disturbance. Summary lithologic information for each hole is plotted along with select physical properties data, including magnetic susceptibility (MS), natural gamma radiation (NGR), gamma ray attenuation (GRA) density, and sediment color reflectance (CIELAB L*, a*, and b*).

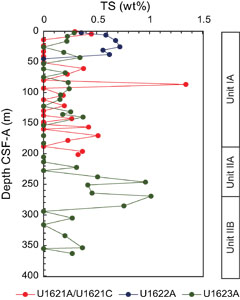

Based on the lithologic characteristics, sediments recovered from Sites U1621–U1623 are divided into two primary lithostratigraphic units and additional subunits (Figures F15, F16; Table T4). Hole U1623A was chosen as the primary site for subdivision, except between ~186 and 202 mbsf where there was poor core recovery; for this depth interval, Hole U1623C was used as the primary source for lithologic information.

Lithostratigraphic Unit I is dominantly composed of soft to firm (dark) gray to greenish gray silty clay with abundant slightly coarser intervals of (dark) reddish gray sandy mud and some diamicton intervals occurring near the unit base (Figures F12, F13). Sand patches (e.g., sediment pellets) and interbedded silty clay and silt layers are characteristic for this unit and are not observed below. Clast content ranges from dispersed to abundant. The unit exhibits variable mineralogy, with some intervals having higher percentages of biogenic material (both calcareous and biosiliceous) and slight to moderate bioturbation that varies largely between different holes and sites. Physical properties (MS, NGR, density, and CIELAB a*) show some cyclic fluctuations between lower and higher values.

Lithostratigraphic Unit II is characterized by a high degree of bioturbation in its upper part that is observed in dark greenish gray to black sediments, whereas its lower part contains increasing amounts of sandy mud that transition into diamicton. Physical properties are variable but without the cyclicity seen in Unit I. Unit II is divided into two subunits (IIA and IIB) with the boundary between the two subunits identified where a significant change in degree of bioturbation from heavy to complete (IIA) to slight (IIB) is encountered.

3.1. Lithostratigraphic unit descriptions

3.1.1. Unit I

- Intervals: 403-U1621A-1H-1 to the bottom of the hole; 403-U1621B-1H-1 to the bottom of the hole; 403-U1621C-1H-1 to the bottom of the hole; 403-U1622A-1H-1 to the bottom of the hole; 403-U1623A-1H-1 through 30X; 403-U1623C-1H-1 through 31X; 403-U1623D-1H-1 to 29X-2, 74 cm; 403-U1623F-1H-1 to the bottom of the hole; 403-U1623G-1H-1 to the bottom of the hole

- Depths: Hole U1621A = 0–206.06 mbsf; Hole U1621B = 0–211.24 mbsf; Hole U1621C = 0–203.19 mbsf; Hole U1622A = 0–46.91 mbsf; Hole U1623A = 0–187.35 mbsf; Hole U1623C = 0–191.63 mbsf; Hole U1623D = 0–178.13 mbsf; Hole U1623F = 0–162.20 mbsf; Hole U1623G = 0–141.86 mbsf

- Age: Holocene to Pleistocene

Sediments of Lithostratigraphic Unit I are predominantly dark gray (5Y 4/1) to gray (5Y 5/1) to greenish gray (10Y 5/1) silty clays with coarser intervals of (dark) reddish gray sandy mud (10R 4/1 to 10R 5/1) (Figures F15, F16, F17). Lithification increases with depth, transitioning from soft to firm in Hole U1621A (139.8 mbsf), Hole U1621B (99.0 mbsf), Hole U1621C (57.2 mbsf), Hole U1623A (82.08 mbsf), Hole U1623C (82.88 mbsf), Hole U1623D (75.40 mbsf), and Hole U1623G (85.79 mbsf).

This unit is characterized by the presence of gravel-sized dispersed to abundant clasts progressively increasing in abundance downhole (Figures F15, F16). At Site U1621, sandy mud with clasts transitions to sandy diamicton at ~190 mbsf. In Hole U1621B, the transition between sandy mud and diamicton occurs also in another four intervals 17–248 cm thick located below ~130 mbsf. Sand patches (<5 mm) and intervals of intercalated silty clay with white silt (<0.3–1 cm) are a dominant feature of Unit I. Clast-rich intervals are generally (but not always) associated with high and fluctuating values of MS, whereas intervals with stable, low values of MS are mostly fine grained with few or no clasts. In Hole U1622A, the uppermost 5.19 m are characterized by silty clay with dark patches; in addition, a nannofossil ooze occurs at ~0.2 mbsf, and the interval 5.19–46.91 mbsf contains mostly very dark gray sandy mud with common clasts. Based on visual observations of the split core surface and examination of X-radiographs, Unit I is generally slightly to moderately bioturbated but also contains large intervals in which no bioturbation is detected; bioturbation is not consistent between holes, and some intervals are thinly to thickly laminated.

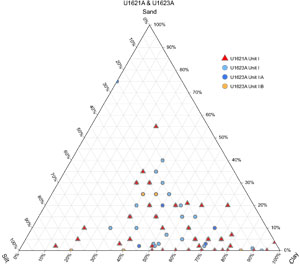

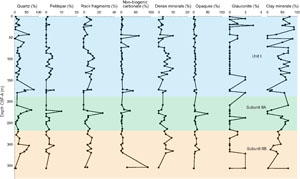

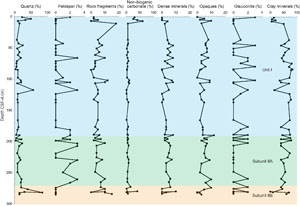

The most common minerals observed in smear slides are clay minerals and quartz. Rock fragments, micas, and dense minerals occur in varying amounts throughout. Glauconite (1%–5%) and opaque minerals (1%–15%), including iron sulfide minerals, are observed discontinuously throughout the sections (Figures F18, F19). Iron sulfide minerals are also sporadically observed on the surface throughout Unit I. Some minor intervals were found to contain high amounts of biogenic components, which indicate a diatom ooze in Core 403-U1623A-7H-3 (51.237 mbsf) and two layers of nannofossil oozes in Cores 10H-6 (70.51 mbsf) and 403-U1622A-1H-1 (0.2 mbsf).

Sand patches are observed in Holes U1621A, U1621B, and U1621C, to 149.16, 125.49, and 190.27 mbsf, respectively, as well as Holes U1623A (186.81 mbsf), U1623C (187.29 mbsf), U1623D (194.40 mbsf), U1623F (90.04 mbsf), and U1623G (126.04 mbsf). Distinct intervals of interbedded silty clay and silt layers occur in the same depth range of the sand patches in Holes U1623A, U1623C, and U1623D but not in Holes U1623F and U1623G, which recovered a shallower stratigraphic record.

Diamicton intervals were described in the lowermost parts of Unit I at Site U1621, downhole of 190.19, 128.03, and 175.87 mbsf in Holes U1621A, U1621B, and U1621C, respectively, and at Site U1623, downhole of 168.58 and 137.21 mbsf in Holes U1623A and U1623C, respectively. Sharp boundaries divide diamicton intervals from the underlying finer grained sediments. The loose gravel and cobble described at the bottom of all holes at Site U1621 are most likely matrix-depleted diamicton that was washed away during drilling.

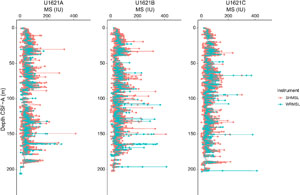

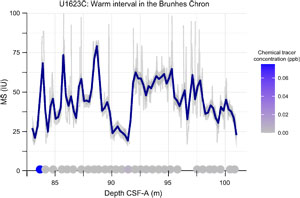

MS in Unit I is mostly in the range of 0–100 IU (Figures F6, F7, F8, F10, F11, F12, F13, F14). The downhole MS curve is characterized by the repeated occurrence of short intervals (as long as 4 m) of stable low values alternating with longer intervals (as long as 10 m) with higher, fluctuating values of MS, mostly corresponding to higher amounts of clasts. Similar near-cyclic changes can also be observed in NGR and density data (Figures F6, F7, F8, F10, F11) as well as in CIELAB a*. CIELAB b* is generally slightly bluish (i.e., slightly negative values) except for the uppermost ~5 m.

3.1.2. Unit II

- Intervals: 403-U1623A-30X to the bottom of the hole; 403-U1623C-31X to the bottom of the hole; 403-U1623D-29X-2, 74 cm, to the bottom of the hole

- Depths: Hole U1623A = 187.35–369.15 mbsf; Hole U1623C = 191.63–366.97 mbsf; Hole U1623D = 178.13–369.54 mbsf

- Age: Pleistocene

Similar to Lithostratigraphic Unit I, sediments of Unit II are predominantly dark gray (5Y 4/1) to gray (5Y 5/1) to greenish gray (10Y 5/1) silty clay with coarser intervals of (dark) reddish gray sandy mud (10R 4/1 to 10R 5/1) (Figures F15, F16, F17) and occasional intervals of diamicton. Unit II is divided into Subunits IIA and IIB based on the distinct occurrence of heavy bioturbation in Subunit IIA. The predominantly firm sediments transition to hard at 349.9 mbsf in Hole U1623A.

The pattern of MS in Unit II differs from Unit I in that the intervals with low MS values are longer but the peaks are slightly more pronounced (Figures F10, F11, F12, F13, F14).

3.1.2.1. Subunit IIA

- Intervals: 403-U1623A-30X through 41X-2; 403-U1623C- 31X through 43X; 403-U1623D-29X-2, 74 cm, through 41X

- Depths: Hole U1623A = 187.35–268.98 mbsf; Hole U1623C = 191.63–271.24 mbsf; Hole U1623D = 178.13–266.61 mbsf

Lithostratigraphic Subunit IIA is characterized by heavily bioturbated sediments, mostly visible from the split core surface, whereas the bioturbation is imperceivable in the X-radiographs (Figure F5C). The sediments appear generally dark in color and are described as dark greenish gray (5GY 4/) to black (N 1/); this is also reflected in lower CIELAB L* values. Clast occurrence in this interval ranges from dispersed to abundant with an associated decrease in bioturbation and absence of laminations.

3.1.2.2. Subunit IIB

- Intervals: base of 403-U1623A-41X-2 to the bottom of the hole; base of 403-U1623C-43X to the bottom of the hole; base of 403-U1623D-41X to the bottom of the hole

- Depths: Hole U1623A = 268.98–369.15 mbsf; Hole U1623C = 271.24–366.97 mbsf; Hole U1623D = 266.61–369.54 mbsf

Lithostratigraphic Subunit IIB is generally characterized by a lower degree of bioturbation and the occurrence of some thinly or thickly laminated intervals. Clasts occur in higher amounts than in Subunit IIA and increase in size downhole; the sediments were hence classified either as matrix (mostly silty clay or sandy mud) with common to abundant clasts or as a diamicton if clasts are >2 cm. These intervals are characterized by slightly higher density values. CIELAB a* shows a distinct downcore increase from values ~1 to ~2 at ~270 mbsf (i.e., slightly more reddish sediments).

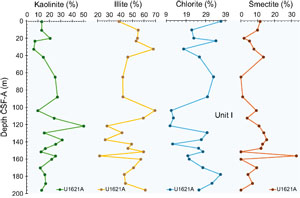

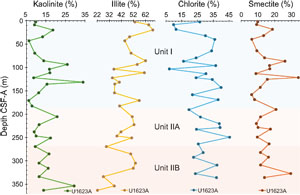

3.2. X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were used to characterize the relative abundances of clay mineral kaolinite, illite, smectite, and chlorite in Holes U1621A and U1623A (Figures F20, F21). The relative abundance of kaolinite ranges 6%–50% (standard deviation [SD] = 9) in Hole U1621A and 7%–34% (SD = 6.21) in Hole U1623A with no significant variation within Lithostratigraphic Unit I, whereas a gradual downhole increase in kaolinite is observed for Unit II. Illite varies from 22% to 69% (SD = 12) in Hole U1621A and 22.2% to 68% (SD = 11) in Hole U1623A, showing a gradual downhole decrease throughout the units. Smectite shows a gradual downhole increase in relative abundance throughout the units, varying from 0% to 33% (SD = 7) in Hole U1621A and 0% to 27% (SD = 7) in Hole U1623A. Chlorite exhibits a gradually increasing trend downhole throughout the units, varying from 11% to 37% (SD = 8) in Hole U1621A and 7.12% to 45% (SD = 10) in Hole U1623A.

Additionally, bulk XRD analysis of select powdered samples confirms that quartz comprises the primary composition of the representative lithologies at given depths (Table T5).

3.3. Preliminary interpretation

The sediments of Lithostratigraphic Unit II are characterized by changes between silty clay without clasts, clast-bearing silty clays, sandy muds with variable amounts of clasts, and diamictons. Physical properties data exhibit cyclicity with relatively long periods, most likely related to glacial–interglacial cycles during the mid-Pleistocene. The lowermost interval (Subunit IIB) is slightly more reddish than the overlying younger sequence, which might point to a change in provenance starting at the Subunit IIB/IIA boundary. One of the delivery areas for sediments of Subunit IIB might be the Barents Sea area, which was subaerial before ~1 Ma when it became a shallow sea (Butt et al., 2002). The presence of diamictons suggests an early glacial influence and a proximal location of an ice sheet or glacier to the drilled site.

The high-bioturbation interval encountered in Subunit IIA coincides with the Jaramillo Subchron (i.e., between Marine Isotope Stages [MISs] 19 and 31), possibly indicating more favorable (warmth and nutrient) conditions during this interval. The base of Unit I contains a glacial diamicton at the approximate depth of Seismic Reflector R3 (0.75 Ma). The presence of this diamicton on the slope is evidence of shelf edge glaciation. It could possibly be associated with a large MIS 20 ice sheet that was also described from north of Svalbard where ice was grounded to ~82°N on the Yermak Plateau (Gebhardt et al., 2011). Unit I at Sites U1621 and U1623 displays uphole changes from clast-bearing silty clays and reddish gray sandy muds and from minor diamictons to homogeneous silty clay without clasts accompanied by changes in MS, NGR, density, and CIELAB a*. These changes most likely represent changes in terrestrial delivery of sediments as MTDs (glacial debris flows) or meltwater plumes, with variable influence in bottom current (WSC) strength (i.e., glacial–interglacial cycles on orbital timescales). The cyclicity of physical properties data, however, is different from Unit II with shorter periodicity, which most likely points at a different style of the glacial–interglacial pattern starting around the mid-Pleistocene transition. Unlike Unit II, sand patches are encountered throughout Unit I sediments. In earlier publications regarding the Norwegian and Greenland seas, similar sand patches were named sediment pellets and interpreted as ice-rafted debris (IRD) (Goldschmidt et al., 1992). Whether the sediment pellet IRD at the Bellsund sites were iceberg or sea ice transported is to be determined.

Site U1622 was drilled ~8 km from Sites U1621 and U1623 at a water depth of 1705 m. Its uppermost ~5 m contain silty clays without clasts but include a nannofossil-rich uppermost layer. The entire sequence below ~5 m consists of sandy mud with mostly common clasts. This site most likely recovered a post–last glacial sequence overlaying a thick (>40 m) glaciogenic debrite that is part of the Storfjorden TMF.

4. Biostratigraphy and paleoenvironment

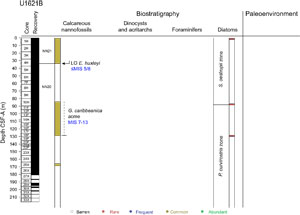

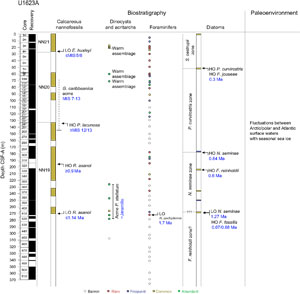

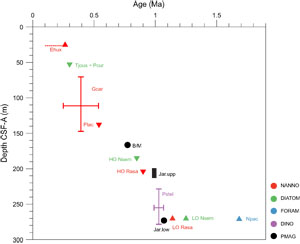

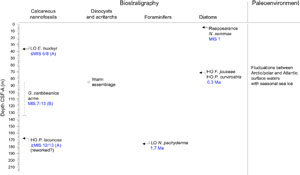

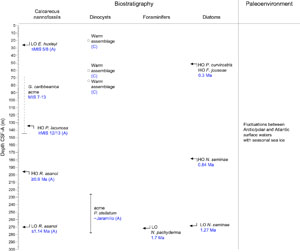

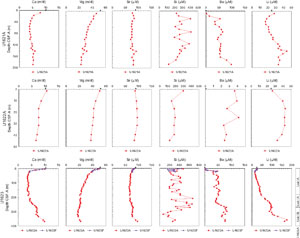

Biostratigraphic and paleoenvironmental characterization of Sites U1621–U1623 was conducted with the analysis of calcareous nannofossils, dinoflagellate cysts (dinocysts), diatoms, and planktonic foraminifers. For calcareous nannofossils and diatoms, all core catchers from Hole A at Sites U1621–U1623 were studied, as well as the deepest core catcher in Hole U1623D, which is located at an absolute CSF-A depth below Hole A. Additional samples were selected for smear slide analyses from the working halves of Holes U1621A–U1621C, U1622A, U1623A, and U1623C. Planktonic foraminifers were studied in all core catchers from Holes U1621A and U1623A, in addition to the uppermost five core catcher samples from Hole U1622A. Additional samples from targeted levels, based on lithologic and physical properties, as well as the shipboard biostratigraphic evidence from other micropaleontological groups, were analyzed for foraminifers and dinocysts in Holes U1621A and U1623A. Dinocysts were analyzed at targeted levels, based on the same evidence as described, in Holes U1621A, U1623A, and U1623C. Additional dinocyst analysis was carried out to identify mid-Pleistocene biostratigraphic events using selected core catcher samples from Hole U1623A. Site U1622 was not investigated for dinocysts (Figures F22, F23, F24, F25, F26). Calcareous nannofossils are generally present at Sites U1621–U1623 but regularly alternate with barren intervals in the record. The studied sites are almost barren of diatoms, except for some intervals with high abundances. Planktonic foraminifers are found continuously in the upper part of Holes U1621A and U1623A (Figures F22, F27), partially downhole, and then completely disappear in the lowermost part of both sites. Compared to calcareous nannofossils, planktonic foraminifers disappear higher in the holes and earlier at both sites. Most of the studied samples have abundant dinocysts, but a few are barren (Figures F22, F23, F24, F25, F26). Combined biostratigraphic information from all groups, together with paleomagnetic data, indicates a Late/Middle Pleistocene age for the sediments recovered at Sites U1621 and U1622 and mid-Pleistocene age for Site U1623 (Figures F25, F27, F28, F29, F30; Tables T6, T7, T8). All microfossil groups together indicate a surface Arctic–polar paleoenvironment under the influence of Atlantic waters and (seasonal) sea ice conditions.

4.1. Calcareous nannofossils

The analysis of calcareous nannofossils at Sites U1621–U1623 is based on the examination of 26 core catchers from Hole U1621A (Figure F22), 7 from Hole U1622A (Figure F25), and 51 from Hole U1623A (Figure F26). In addition, 140 levels were selected from split core sections (working halves) from Site U1621 (Holes U1621A–U1621C), 7 from Hole U1622A, and 163 from Site U1623 (Holes U1623A and U1623C) for smear slide preparation and calcareous nannofossil analysis (Figures F22, F23, F24, F25, F26). The strategy for sample selection from the working halves followed the dominant patterns in sediment color and physical properties (i.e., changes in MS and/or NGR).

The representation of calcareous nannofossils in sediments from Site U1621 is generally constant, with a few exceptions. In the uppermost ~25 m of the three holes, the concentration of specimens in samples ranges between abundant and common (Figures F22, F23, F24). The abundances of calcareous nannofossils decrease toward the lowermost sections. Alternance of barren or almost barren intervals becomes a prominent feature below ~30 mbsf in the three holes (Figures F22, F23, F24). Overall, when the calcareous nannofossils are present below ~30 mbsf, the abundance is frequent to common. Additionally, there are few levels with an abundant concentration of calcareous nannofossils (Figures F22, F23, F24). Calcareous nannofossils are abundant to common in the uppermost 2.98 m of Hole U1622A and barren toward the bottom of the hole (Figure F25). At Site U1623, calcareous nannofossil specimens are generally present with some intermittent barren intervals in Hole U1623A. A more continued barren interval is registered at this site from 272.25 mbsf toward the end of the section (Figures F26, F30). The concentration of specimens in samples generally ranges between frequent and common, in addition to some few levels recording an abundant representation of nannofossils (Figure F26).

Calcareous nannofossil assemblages at Sites U1621–U1623 show low diversity. A total of 10 groups/taxa compose the studied assemblages, including Emiliania huxleyi, small Gephyrocapsa, Gephyrocapsa caribbeanica, medium Gephyrocapsa, Pseudoemiliania lacunosa, Reticulofenestra asanoi < 6 µm and R. asanoi > 6 µm, Coccolithus pelagicus, Calcidiscus leptoporus, and Helicosphaera carteri (Figures F25, F28, F30). The state of preservation is good to moderate. Reworked nannofossils from older stratigraphic levels are intermittently present in the sequences, with an abundance that ranges from frequent to common.

Two calibrated events were identified in the three holes at Site U1621, one in Hole U1622A, and four in Hole U1623A (Figures F25, F28, F30). The determination of these calibrated events is complemented with the identification of acme events and age ranges extracted from the presence of additional species in the studied assemblages. Calcareous nannofossil information suggests a Late Pleistocene age for Sites U1621 and U1622 (Figures F25, F28) and a Middle to Late Pleistocene age for Site U1623 (Figure F30).

The lowest occurrence (LO) of E. huxleyi is observed in Holes U1621A–U1621C (Samples 403-U1621A-5H-6, 53 cm, 403-U1621B-4H-6, 31 cm, and 403-U1621C-4H-5, 37 cm) (Figures F22, F23, F24, F28); in Hole U1622A (Sample 2H-1, 18 cm) (Figure F25); and in Hole U1623A (Sample 4H-4, 54 cm) (Figures F26, F30). According to the global calibration for this event, the 280 ka boundary, at MIS 8, can be identified (Thierstein et al., 1977). Because the regional biostratigraphic characterization of this species for Arctic sediments (Razmjooei et al., 2023) places its LO up to MIS 5 (130 ka), a younger age ranging up to this boundary could be established for the uppermost section of Sites U1621–U1623. Following the zonation by Martini (1971), this boundary determines the transition between Zones NN21 and NN20 and the correspondence to Zone NN21 of Martini (1971) for the uppermost sections from Holes U1621A (37.49 mbsf), U1621B (35.27 mbsf), U1621C (25.34 mbsf), U1622A (2.98 mbsf), and U1623A (27.48 mbsf) (Figures F22, F26, F30).

The acme event of G. caribbeanica is identified between 83.89 and 132.43 mbsf in Holes U1621A–U1621C (Figures F22, F23, F24, F28) and between 69.77 and 146.14 mbsf in Hole U1623A (Figures F26, F30). The observation of this acme episode determines an age interval spanning between MISs 7 and 13 (191–524 ka) for the indicated depth interval (Flores et al., 2012; González-Lanchas et al., 2023; Razmjooei et al., 2023). The highest occurrence (HO) of P. lacunosa is recorded in Samples 403-U1621A-24X-CC, 175.90 cm, and 403-U1621C-22F-80, 171.32 cm (Figures F22, F23, F28). However, a high abundance of reworked specimens from various older stratigraphic intervals, including Cretaceous, Miocene/Pliocene, and also the Early to Middle Pleistocene (i.e., R. asanoi) hampers the complete discrimination of P. lacunosa specimens as in situ or reworked at the indicated levels, obscuring the assignation of the calibrated 430/524 ka boundary (Thierstein et al., 1977; Backman et al., 2012; Razmjooei et al., 2023) and the identification of the Zone NN20–NN21 transition (Martini, 1971). As such, the lowermost sequence in Holes U1621A–U1621C is placed in Zone NN20 (Figure F28). At Site U1623, the HO of P. lacunosa is recorded at 138.72 mbsf (Sample 24F-CC, 54 cm) in Hole U1623A. According to the global calibration (Thierstein et al., 1977; Backman et al., 2012) and regional revision of this event (Razmjooei et al., 2023), the 440/524 ka boundary, within MISs 12/13, could be identified at 138.72 mbsf in Hole U1623A. This depth marks the transition between Zones NN20 and NN19 by Martini (1971) (Figure F25).

The HO and LO of R. asanoi > 6 µm is registered for Hole U1623A in Samples 33X-2, 59 cm, and 41X-3, 107 cm, respectively (Figures F25, F27). Following the global calibration and determinations about the occurrence of this taxa (Wei, 1993; Raffi, 2002; Bown, 1998), an age range spanning between 0.9 and 1.14 Ma could be assigned to the interval constrained by the presence of this species, between 204.05 and 270.05 mbsf (Figures F25, F27). Following this determination, this part of the section is identified to correspond to Zone NN19 by Martini (1971). The lowest core catcher in Hole U1623D (Sample 56X CC) is located at 369.2 mbsf, below the maximum depth drilled in Hole U1623A. The species R. asanoi was not identified in this sample, possibly determining an age older than the 1.14 Ma boundary. Specimens belonging to large Gephyrocapsa were identified in this sample, indicating an age that could span between 1.25 and 1.6 Ma, according to the calibration by Raffi et al. (2006). Further examination at a higher resolution in Hole U1623D is required to accurately determine this tentative lowermost boundary.

4.2. Diatoms and silicoflagellates

The study of diatoms at Sites U1621–U1623 is based on the examination of 26 core catchers from Site U1621 (Figures F22, F23, F24), 7 from Site U1622 (Figure F25), and 44 from Site U1623 (Figure F26). Additionally, 295 samples selected from split core sections were considered: 143 from Site U1621 (Holes U1621A–U1621C) (Figures F22, F23, F24), 7 from Site U1622 (Figure F25), and 163 from Site U1623 (Holes U1623A, U1623C, and U1623D) (Figure F26). The analyses reveal that most of the samples from all sites are almost barren of diatoms, except in the uppermost sections and particular levels at Sites U1621 and U1623 (Figures F22, F23, F24, F26, F30).

In the uppermost parts of Sites U1621–U1623, the diatom record displays a diverse and well-preserved diatom assemblage. Abundance varies from frequent to abundant, and the preservation ranges between moderate and good. The most abundant species belong to the genus Chaetoceros in resting spore stage (RS). This species is common in nutrient-rich waters but, due to its degree of silicification, is also resistant to dissolution (Barron et al., 2016). Moreover, the assemblage includes species Bacteriosira bathyomphala, Fragilariopsis oceanica, Fragilariopsis cylindrus, Fragilariopsis regina-jahniae, or Thalassiosira nordenskioeldii, which have a preference for seasonal sea ice; species such as Thalassiosira antarctica var. borealis, Actinocyclus curvatulus, Coscinodiscus radiatus, Rhizosolenia hebetata f. hebetata, and Shionodiscus trifultus, which are related to Arctic–subpolar waters (Oksman et al., 2019); and a third group of species related to north-flowing Atlantic water within the North Atlantic and Norwegian Atlantic currents, such as Coscinodiscus marginatus, Shionodiscus oestrupii, and Thalassionema nitzschioides var. nitzschioides (Oksman et al., 2019) (Figures F22, F23, F24, F25, F26). The presence of Neodenticula seminae was only observed at Site U1623 (Samples 403-U1623A-1H-1, 1 cm, and 1H-2, 67 cm; 0.01–2.14 mbsf), documenting the reentrance of the species in the region at the onset and during MIS 1 (Reid et al., 2007; Miettinen et al., 2013; Matul and Kazarina, 2020) (Figure F26).

The silicoflagellate species Stephanocha speculum is also recorded in the uppermost part of Hole U1621A (Samples 1H-1, 1 cm, and 1H-1, 5 cm) and indicates the presence of cooler and nutrient-rich waters (Rigual-Hernández et al., 2010) (Figure F22).

A second interval with a well-preserved diatom assemblage, with rare to abundant diatom abundance, is similarly observed at Sites U1621 and U1623. At Site U1621, this interval is located between 73.49 and 73.89 mbsf in Hole U1621A (Samples 9H-5, 77 cm, 9H-5, 99 cm, and 9H-5, 117 cm) and between 74.62 and 76.27 mbsf in Hole U1621C (Samples 9H-7, 56 cm, 9H-7, 102 cm, and 10H-1, 7 cm) (Figures F22, F24). In Hole U1621B, only fragments of Proboscia curvirostris were found in Sample 10H-6, 89 cm (88.27 mbsf) (Figure F23). At Site U1623, this interval is recognized in Hole U1623A at 51.5 mbsf (Sample 7H-3, 55 cm). Assemblages are composed of abundant C. marginatus, A. curvatulus, and Thalassiothrix longissima, in addition to less abundant B. bathyomphala, F. cylindrus, F. oceanica, Paralia sulcata, S. trifultus, T. nordenskioeldii, T. nitzschioides var. nitzschioides, and Chaetoceros. This fossil assemblage is similar to modern assemblages in the region (Oksman et al., 2019).

The calibrated events HO of P. curvirostris and the HO of Thalassiosira jouseae were identified in the upper part of the interval described above at Sites U1621 and U1623. Koç et al. (1999) described both events to be synchronous between the middle and high latitudes of the North Atlantic, the North Pacific, and the Nordic Seas, with a calibrated age of 0.3 Ma, at MIS 9. Following the aforementioned study, this observation indicates an age older than 0.3 Ma for the top of the interval and the identification of the base of the S. oestrupii Zone, as well as the top of the P. curvirostris Zone, at 73.49 mbsf in Hole U1621A and 51.5 mbsf in Hole U1623A (Figures F22, F23, F24).

A third interval with diatom content is recorded at Site U1623 between 58 and 61.5 mbsf in Samples 403-U1623A-8H-CC, 15 cm, 8H-CC, 30 cm, 8H-CC, 9F-1, 25 cm, 9F-2, 38 cm, 9F-2, 68 cm, and 9F-3, 55 cm (Figures F26, F30). The species P. curvirostris and T. jouseae are identified, constraining this interval within the P. curvirostris Zone. The diatom assemblage at this part of the sequence contains North Atlantic–Norwegian surface waters–related taxa, such as C. marginatus, S. oestrupii, and T. nitzschioides var. nitzschioides, indicating interglacial conditions (Oksman et al., 2019).

The HO of P. curvirostris (0.3 Ma) defines the top of the P. curvirostris Zone (Koç and Flower, 1998), whereas the base is defined for the HO of N. seminae (0.84–0.85 Ma). In this study, the HO of N. seminae was observed in Hole U1623A in Sample 30X-CC (187.32 mbsf), allowing the identification of the base of the P. curvirostris Zone at this site (187.32 mbsf; Figure F26). The species Fragilariopsis reinholdii and Fragilariopsis fossilis are scarce along this hole, probably due to poor preservation. The HO of both species was identified at 208.1 and 270.1 mbsf. According to Koç et al. (1999), the HO of F. reinholdii is located within MIS 15, with an estimated age of 0.6 Ma, and the HO of F. fossilis at around 0.675/0.687 Ma at the end of MIS 17. However, the scarcity of our record along the sequence does not allow the identification of these boundaries in Hole U1623A.

The N. seminae Zone is defined by the HO of N. seminae at the top and the LO of N. seminae at the base, between 1.25 and 1.26 Ma (Koç et al., 1999). This biozone was identified by the recognition of these events in Hole U1623A (Figure F26). Within this zone, as well as toward the base of the P. curvirostris Zone, five intervals with a good to moderately preserved diatom assemblage were observed (Figure F26). The first interval extends from 176.33 to 187.32 mbsf in Samples 403-U1623A-29X-7, 96 cm, and 30X-CC. The second interval was observed between 204.05 and 211.225 mbsf in Samples 33X-2, 59 cm, and 33X-CC. A third interval of shorter extent was observed from 235.925 to 236.57 mbsf in Samples 36X-CC to 37X-2, 117 cm. The fourth interval extends from 249.51 to 253.45 mbsf in Samples 36X-CC to 37X-2, 117 cm. The fifth interval was recognized between 268.06 and 272.275 mbsf in Samples 41X-2, 57 cm, to 41X-CC (Figure F26). The LO of N. seminae was recorded at 270.05 mbsf (Core 41X). All samples analyzed are barren of diatoms below this level, obscuring the determination of this LO event.

The remaining flora accompanying the marker species is mostly composed of the species S. oestrupii, T. nitzschioides var. nitzschioides, C. marginatus, and Hemidiscus cuneiformis. These species are related to Atlantic waters of Norwegian–North Atlantic origin (Barron et al., 2016; Miettinen, 2018; Oksman et al., 2019). Complementary, the species B. bathyomphala or T. antarctica var borealis, S. trifultus, and R. hebetata f. hebetata were observed in samples. These species constitute an Arctic water assemblage with seasonal sea ice influence (Barron et al., 2016; Miettinen, 2018; Oksman et al., 2019) (Figure F30).

Holes U1623C and U1623D were targeted to find preserved diatoms during supposed interglacial periods. The HO of P. curvirostris was recorded in Sample 403-U1623C-36X-2, 65 cm, and indicates an age older than 0.3 Ma. Aside from this observation, most of the analyzed samples in these holes are barren of diatoms, except Samples 12F-2, 75 cm (89.32 mbsf), 36X-1, 121 cm (210.01 mbsf), and 36X-2, 65 cm (210.95 mbsf), where traces to rare entire diatoms were observed.

Except in the uppermost part of Hole U1621A, silicoflagellates are absent across the three sites.

4.3. Dinoflagellate cysts and acritarchs

Sites U1621 and U1623 were expected to recover sediments from the Late Pleistocene, a time interval that has no clear dinocyst biostratigraphic markers. Here, however, interglacial stages can be detected using ecostratigraphy, specifically using elevated dinocyst concentrations and/or the peak abundance of index species (e.g., Matthiessen et al., 2018). Concentration maxima are usually associated with interglacials (e.g., Matthiessen and Knies, 2001; Van Nieuwenhove et al., 2011). Unfortunately, concentrations could not be calculated with the nonacid preparation technique we used. Interglacials are often characterized by a high abundance of cysts of Protoceratium reticulatum, but this is an opportunistic species that can also be occasionally abundant during glacials (e.g., Matthiessen et al., 2018).

Dinocysts were analyzed in a total of 28 samples from Holes U1621A (7), U1621C (4), U1623A (13), and U1623C (4) (Figures F22, F24, F28, F30). A targeted sampling strategy was used to identify interglacial intervals, based on lithologic and physical properties, together with evidence from the study of other microfossil groups. Core catchers were analyzed in Hole U1623A to identify mid-Pleistocene biostratigraphic events (e.g., around the Jaramillo Subchron) because that drill hole went deeper than the holes at Site U1621.

Most samples contain abundant dinocysts. Samples 403-U1621A-4H-CC and 5H-2 and Core 50X are barren. A total of 22 different dinocyst taxa were recorded. Assemblages are low in diversity (1–14 taxa per sample), and most have good to excellent preservation. The number of cysts per sample is rather high, suggesting the nonacid preparation method works rather well in the Pleistocene of this region. Acritarchs were not encountered. Occasionally, the freshwater algae Pediastrum was recognized in Hole U1623A. Remains of terrestrial material are common in almost all the studied samples. Reworked terrestrial palynomorphs occur in most samples and are always more abundant than reworked dinocysts and acritarchs.

The dinocyst assemblages from Sites U1621 and U1623 are dominated by round brown cysts (RBCs), Brigantedinium, and P. reticulatum. Frequently encountered taxa are Bitectatodinium tepikiense, Nematosphaeropsis labyrinthus, and Spiniferites (Spiniferites mirabilis and Spiniferites spp.). Islandinium brevispinosum is dominant in Sample 403-U1623A-3H-5, 50–51 cm. Cysts of Protoperidinium stellatum are abundant in the lower part of Hole U1623A, around the Jaramillo Subchron.

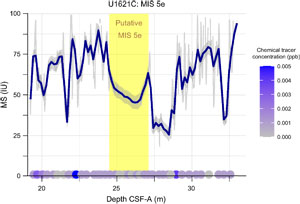

Establishing an ecostratigraphy that identifies Pleistocene interglacials requires high-resolution sampling (Matthiessen et al., 2018). This was not possible during Expedition 403 due to time constraints. Initially, most investigated samples indicated nutrient-rich environments and cool, arctic water conditions with (seasonal) sea ice cover. Those samples were dominated by heterotrophic taxa like Brigantedinium and RBCs, as well as I. brevispinosa (Sample 403-U1623A-3H-6, 25–26 cm). After fine-tuning the targeted sampling strategy, using lithologic and physical properties, and biostratigraphic evidences from other microfossil groups, it was observed that several investigated samples record a warm, interglacial assemblage characterized by the abundant to dominant P. reticulatum (e.g., Samples 403-U1621A-10H-7, 44–45 cm, 403-U1621C-11H-2, 80–90 cm, 403-U1623A-3H-5, 50–51 cm, 9F-2, 68–69 cm, and 42X-CC) and/or S. mirabilis (e.g., Samples 403-U1621A-10H-7, 44–45 cm, 403-U1621C-4H-5, 55–65 cm, and 403-U1623A-10H-6, 90–91 cm). In Hole U1623C, a succession of a sea ice–covered environment was documented (Sample 3H-6, 25–26 cm), followed by an Atlantic water–dominated environment (Sample 3H-5, 50–51 cm) and a cool–temperate environment (Sample 3H-4, 45–46 cm) as the most abundant species changed from I. brevispinosum to P. reticulatum and finally B. tepikiense. This sequence may correspond to MIS 5 (de Vernal et al., 2020). Warm conditions with Atlantic water influence identified deeper in the record likely correspond to the MIS 7–11 interglacials (e.g., Samples 403-U1621A-10H-7, 44–45 cm, 403-U1621C-11H-2, 80–90 cm, and 403-U1623A-10H-6, 90–91 cm) and possibly to MIS 29–37 (Samples 42X-CC and 45X-CC). Further analyses on high (millennial-scale) resolution will be required to identify each MIS.

In Samples 403-U1623A-35X-CC, 38X-4, 52–53 cm, 41X-CC, and 42X-CC, P. stellatum was recorded. This species is present in higher abundance in Sections 38X-4 and 42X-CC. Comparable to its record at Sites U1618–U1620 and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Hole 911A (Matthiessen and Brenner, 1996), it also occurs here around the Jaramillo Subchron paleomagnetic boundary, further confirming its potential as a good regional biostratigraphic marker. In Hole U1623A, it appears to be present during the entire Jaramillo Subchron, but the uppermost occurrence may range higher than Section 35X-CC.

4.4. Foraminifers

All core catcher samples from Holes U1621A (25) and U1623A (39) were analyzed for planktonic foraminifers. Some additional samples (12) from the split core sections (working halves) were also analyzed to help identify targeted interglacial periods at these holes. Additional samples from split core sections (working halves) from Hole U1623C (3) were selected for this purpose.

Planktonic foraminifers are continuously present in the upper part of Holes U1621A and U1623A. Barren intervals are encountered downcore at both sites, becoming increasingly frequent toward the bottom of the holes (Figures F22, F27). Observations show that the tests are highly abraded, encrusted, and/or dissolved. There are none or very few fragments. Neogloboquadrina pachyderma is present in all samples with a foraminiferal content, placing Holes U1621A and U1623A within the Pleistocene (Weaver and Clement, 1986). N. pachyderma strongly dominates all samples, and Globigerinita bulloides was also observed in most of the samples, but with rare occurrences. Turborotalita quinqueloba is also present in some samples.

The observed fauna assemblage is common for Arctic regions, indicating an influence of Arctic–polar surface water masses and seasonal sea ice (e.g., Husum and Hald, 2012; Schiebel and Hemleben, 2017). Additional samples were taken from Hole U1621A in the working halves of Cores 3H–7H, between 18.7 and 53.4 mbsf, to identify potential interglacial conditions (Figure F22). All samples are dominated by N. pachyderma with the presence of G. bulloides and T. quinqueloba, but one sample at 37.5 mbsf (Sample 5H-6, 52–54 cm) shows increased and frequent abundance of T. quinqueloba. T. quinqueloba is found mainly within warmer Atlantic water masses in this region and is highly abundant at oceanographic fronts (e.g., Husum and Hald, 2012). However, its current abundance is not high enough to resemble fully interglacial conditions (e.g., Pados and Spielhagen, 2014; Chauhan et al., 2014). Similar additional sampling at assumed interglacial periods were also carried out from Hole U1623A in Cores 3H (18.7–20.8 mbsf), 9F (60.2–63.1 mbsf), 10H (70.6 mbsf), and 30X (186.4 mbsf) (Figure F27). All samples are also dominated by N. pachyderma with presence of G. bulloides and T. quinqueloba, but nothing seemed to indicate the warmer water masses. It must be mentioned that T. quinqueloba is a relatively small species that may be underrepresented in the current >125 μm size fraction (e.g., Carstens and Wefer, 1992; Bauch, 1994; Husum and Hald, 2012).

Four core catcher samples from Hole U1622A were prepared and analyzed with regard to planktonic foraminifers before the site was ended. Only the two uppermost samples (1H-CC and 2H-CC) contain foraminifers, ranging from frequent to rare. The dominant species is N. pachyderma. A few specimens of G. bulloides and T. quinqueloba were also observed. Preservation is relatively poor with tests showing a high degree of abrasion and/or dissolution. Sample 2H-CC also contains some few benthic foraminifers. Overall, both faunas seemed to have been reworked. The remaining two core catcher samples (3H-CC and 4H-CC) are barren.

5. Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetic investigation at Sites U1621–U1623 focused on measurements of the natural remanent magnetization (NRM) before and after alternating field (AF) demagnetization of archive-half sections and vertically oriented discrete cube samples. All archive-half sections were measured except some that had significant visible coring disturbance and the core catchers. APC and HLAPC archive-half sections were measured before and after 10 and 15 mT peak AF demagnetization, except Cores 403-U1623C-1H (all sections) and 2H (Sections 1–3), which were accidentally demagnetized to 30 mT peak AF. Because XCB cores do not use nonmagnetic core barrels and are more susceptible to the viscous isothermal remanent magnetization (VIRM) drill string overprint (Richter et al., 2007), XCB archive-half sections required higher AF demagnetization steps to remove this overprint and were measured before and after 15 and 30 mT peak AF demagnetization. Several XCB cores were measured with the APC core protocol by mistake, including all sections of Cores 403-U1621B-21X, 23X, 24X, and 403-U1621C-23X through 27X, and only experienced peak AF demagnetization of 15 mT.

Although not as common as at previous sites drilled during Expedition 403 (see Paleomagnetism in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b], Paleomagnetism in the Site U1619 chapter [St. John et al., 2026a], and Paleomagnetism in the Site U1620 chapter [St. John et al., 2026b]), some archive-half sections from Sites U1621 and U1623 with high MS (above ~750 IU) had NRM intensities that were too strong to be measured on the superconducting rock magnetometer (SRM) and caused flux jumps (Bowles, 2009) even when the track speed was slowed by 10×, thus compromising our ability to collect quality data in these intervals. However, at Sites U1621 and U1623, the problem was only observed in XCB-cored intervals, and the 30 mT peak AF demagnetization step was typically great enough to reduce the magnetization to levels that could be measured without causing flux jumps.

The archive section half data were supplemented by the study of discrete cube samples for which we could be more selective with the sampling interval, subject to more detailed AF demagnetization of the NRM, and study the rock magnetic properties of the sediment. In Hole U1623A, noisy archive-half data suggested the potential for reverse and normal polarity intervals in XCB cores recovered below around 160 mbsf; however, this noise could largely be attributed to coring disturbance, limiting our ability to confidently identify polarity zones and boundaries. Based on previous success with discrete cube samples at Site U1620 for defining polarity intervals in shallower XCB cores below the depths of APC refusal but above where sediments become more consolidated and have better XCB recovery (see Paleomagnetism in the Site U1620 chapter [St. John et al., 2026b]), we sampled this interval from Cores 403-U1623A-27X through 43X at higher resolution (~1 sample per section when possible), targeting larger intact biscuits and intervals of lower MS. Lower MS intervals were targeted to avoid potential iron sulfide nodules that have been commonly observed at deeper depths (greater than ~100–200 mbsf) in the region (see Paleomagnetism in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b], Paleomagnetism in the Site U1619 chapter [St. John et al., 2026a], and Paleomagnetism in the Site U1620 chapter [St. John et al., 2026b]; c.f. ODP Leg 151 results [Shipboard Scientific Party, 1995]). This strategy likely imposes a bias toward the magnetic properties of these lower MS in our shipboard results, and future work should consider this limitation. The NRMs of the oriented discrete cube samples were stepwise demagnetized before and after 0, 5*, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50* mT peak AF using the SRM and in-line AF demagnetization system (* = the 5 and 50 mT steps were not used for Hole U1623A samples to keep up with core flow). These measurements were supplemented by measurements of the MS and anhysteretic remanent magnetization (ARM). ARMs of APC/HLAPC-cored and some XCB-cored sections were measured before and after 0, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40 peak AF demagnetization to allow for comparison between NRM and ARM coercivity. ARMs of the remaining XCB-cored sections were measured before and after 30 mT peak AF demagnetization.

An additional sample was taken from Section 403-U1623D-55X-2 where we observed an authigenic nodule that was associated with high MS (>1500 IU). The sample was unoriented, but it was removed as an intact piece and mounted in a paleomagnetic cube. Bulk MS, frequency-dependent MS, ARM, and isothermal remanent magnetizations (IRMs) were measured to compare this nodule to previous nodules that were studied in detail at Sites U1618 and U1619.

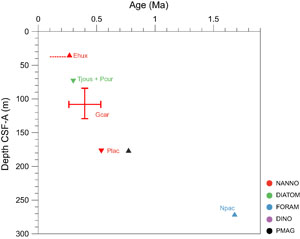

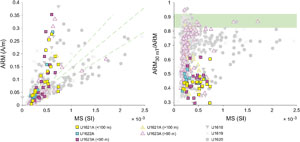

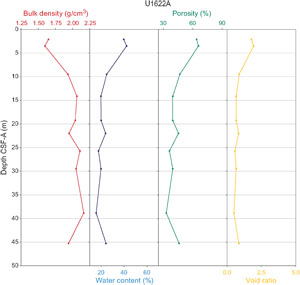

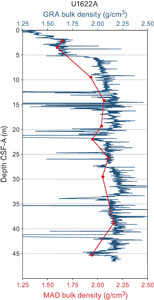

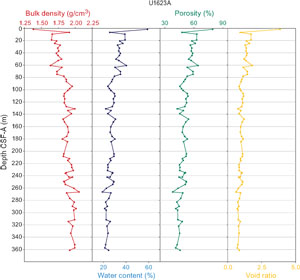

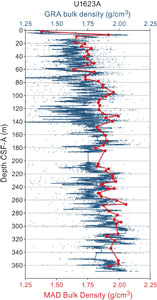

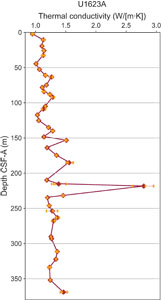

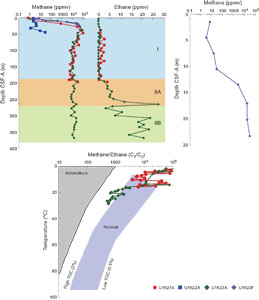

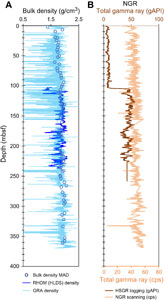

5.1. Sediment magnetic properties

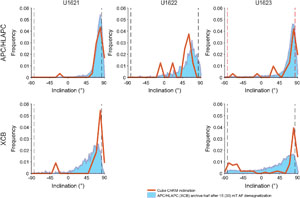

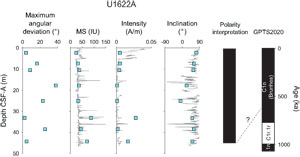

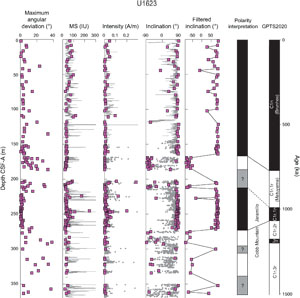

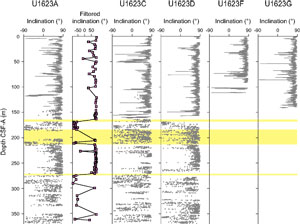

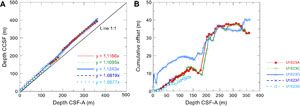

Sites U1621–U1623 have magnetic properties that likely represent contributions from detrital and authigenic sources with some similarity, but also major differences, to previous sites drilled during Expedition 403 (see Paleomagnetism in the Site U1618 chapter [Lucchi et al., 2026b], Paleomagnetism in the Site U1619 chapter [St. John et al., 2026a], and Paleomagnetism in the Site U1620 chapter [St. John et al., 2026b]). Based on MS and ARM data, Sites U1621 and U1623 can broadly be classified into three magnetic zones with similar depth ranges (Figure F31). Magnetic Zone 1 (Hole U1621A = 0–38 mbsf; Hole U1623A = 0–25 mbsf) is characterized by higher and variable ARM intensities, low ARM coercivity (tracked by the ratio of the ARM after 30 mT peak AF demagnetization and the initial ARM [ARM30mT/ARM]), and high ARM/MS ratios. Magnetic Zone 2 (Hole U1621A = 38–100 mbsf; Hole U1623A = 25–90 mbsf) has similar lower ARM coercivities but also lower ARM intensity. Data from Hole U1622A, which only recovered material in the uppermost 50 m, are similar to those in these two magnetic zones, but they do not show a clear transition between the two. Some of the variability observed in these units may be related to sampling specific lithology and could be explored further with additional higher resolution sampling. Magnetic Zone 3 (Hole U1621A = below 100 mbsf; Hole U1623A = below 90 mbsf) is defined by higher and more variable ARM coercivities. In Hole U1623A, we divide this interval into two subzones (Magnetic Zones 3a and 3b) because Whole-Round Multisensor Logger (WRMSL) MS values from 90 to 212 mbsf are similar to those observed in Magnetic Zones 1 and 2, whereas below 212 mbsf there are frequent peaks in the WRMSL MS greater than 500 IU (see Figure F45). Hole U1621A did not reach similar depths and does not have MS peaks of this magnitude.