Hodell, D.A., Abrantes, F., Alvarez Zarikian, C.A., and the Expedition 397 Scientists

Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program Volume 397

publications.iodp.org

https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.397.102.2024

Expedition 397 methods1

![]() F. Abrantes,

F. Abrantes,

![]() D.A. Hodell,

D.A. Hodell,

![]() C.A. Alvarez Zarikian,

C.A. Alvarez Zarikian,

![]() H.L. Brooks,

H.L. Brooks,

![]() W.B. Clark,

W.B. Clark,

![]() L.F.B. Dauchy-Tric,

L.F.B. Dauchy-Tric,

![]() V. dos Santos Rocha,

V. dos Santos Rocha,

![]() J.A. Flores,

J.A. Flores,

![]() T.D. Herbert,

T.D. Herbert,

![]() S.K.V. Hines,

S.K.V. Hines,

![]() H.-H.M. Huang,

H.-H.M. Huang,

![]() H. Ikeda,

H. Ikeda,

![]() S. Kaboth-Bahr,

S. Kaboth-Bahr,

![]() J. Kuroda,

J. Kuroda,

![]() J.M. Link,

J.M. Link,

![]() J. McManus,

J. McManus,

![]() B.A. Mitsunaga,

B.A. Mitsunaga,

![]() L. Nana Yobo,

L. Nana Yobo,

![]() C.T. Pallone,

C.T. Pallone,

![]() X. Pang,

X. Pang,

![]() M.Y. Peral,

M.Y. Peral,

![]() E. Salgueiro,

E. Salgueiro,

![]() S. Sanchez,

S. Sanchez,

![]() K. Verma,

K. Verma,

![]() J. Wu,

J. Wu,

![]() C. Xuan, and

C. Xuan, and

![]() J. Yu2

J. Yu2

1 Abrantes, F., Hodell, D.A., Alvarez Zarikian, C.A., Brooks, H.L., Clark, W.B., Dauchy-Tric, L.F.B., dos Santos Rocha, V., Flores, J.-A., Herbert, T.D., Hines, S.K.V., Huang, H.-H.M., Ikeda, H., Kaboth-Bahr, S., Kuroda, J., Link, J.M., McManus, J.F., Mitsunaga, B.A., Nana Yobo, L., Pallone, C.T., Pang, X., Peral, M.Y., Salgueiro, E., Sanchez, S., Verma, K., Wu, J., Xuan, C., and Yu, J., 2024. Expedition 397 methods. In Hodell, D.A., Abrantes, F., Alvarez Zarikian, C.A., and the Expedition 397 Scientists, Iberian Margin Paleoclimate. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 397: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.397.102.2024

2 Expedition 397 Scientists’ affiliations.

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the procedures and methods employed for coring operations and in the shipboard laboratories of the R/V JOIDES Resolution during International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 397. The laboratory information applies only to shipboard work described in the Expedition Report section of the Expedition 397 Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program volume that includes the shipboard sample registry, imaging and analytical instruments, core description tools, and the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) database. The shipboard workflow followed standard IODP procedures (as previously described by, e.g., Huber et al., 2019; Winckler et al., 2021; Planke et al., 2023), with revisions and refinements as described in this chapter. Methods used by investigators for shore-based analyses of Expedition 397 data will be documented in separate publications.

All shipboard scientists contributed to this volume with the following primary responsibilities (authors are listed in alphabetical order; see Expedition 397 scientists for contact information):

Summary chapter: Expedition 397 Scientists

- Background and objectives: F. Abrantes, D. Hodell

- Operations: C.A. Alvarez Zarikian, K. Grigar

- Lithostratigraphy: H.L. Brooks, J.M. Link, J. McManus, C. Pallone, X. Pang, E. Salgueiro, V. dos Santos Rocha, J. Yu

- Biostratigraphy: C.A. Alvarez Zarikian, W. Clark, J.-A. Flores, M. Peral, K. Verma

- Paleomagnetism: L. Dauchy-Tric, C. Xuan

- Geochemistry: S. Hines, B. Mitsunaga, L. Nana Yobo, J. Wu

- Physical properties and downhole measurements: H.-H.M. Huang, H. Ikeda, J. Kuroda, S. Sanchez

- Stratigraphic correlation: T. Herbert, H.-H.M. Huang, S. Kaboth-Bahr

This introductory section provides an overview of drilling and coring operations, core handling, curatorial conventions, depth scale terminology, and the sequence of shipboard analyses. Subsequent sections of this chapter document specific laboratory instruments and methods in detail.

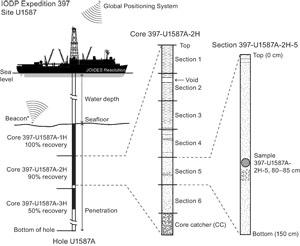

1.1. Operations

The IODP Environmental Protection and Safety Panel (EPSP) approved four primary and two alternate drilling sites for Expedition 397 as described in the expedition Scientific Prospectus (Hodell et al., 2022). The proposed sites encompass a depth transect (1304–4686 meters below sea level [mbsl]) off the Portuguese margin across the Promontório dos Principes de Avis. The shipboard GPS navigation system (WGS84 datum) was used to position the vessel at Expedition 397 sites. A SyQwest Bathy 2010 CHIRP subbottom profiler was used to monitor seafloor depth during the approach to each site to confirm the seafloor depth once on site. Once the vessel was positioned at a site, the thrusters were lowered and a seafloor positioning beacon was prepared for deployment in case it was needed. Dynamic positioning control of the vessel was constrained by the navigational input from the GPS system (Figure F1). No seafloor positioning beacons were deployed during this expedition. The final hole position was calculated as the mean position of at least 1000 GPS position fixes since the hole was occupied. The ship’s position is better than 1 m, but the exact position of the hole is less certain because of the deviation of the pipe below the ship, which can vary depending on water currents, tides, and water depth; the hole position is thus known typically within 10 m accuracy.

Drilling sites were numbered according to the series that began with the first site drilled by the D/V Glomar Challenger in 1968. Starting with Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 301, the prefix “U” designates sites occupied by JOIDES Resolution. When drilling multiple holes at a site, hole locations were offset from each other by ~20–100 m. A letter suffix distinguishes each hole drilled at the same site. The first hole drilled is assigned the site number modified by the suffix “A,” the second hole takes the site number and the suffix “B,” and so forth. During Expedition 397, we occupied three new sites, U1586, U1587, U1588, and reoccupied Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 339 Site U1385 and drilled 16 new holes.

1.2. JOIDES Resolution standard coring systems

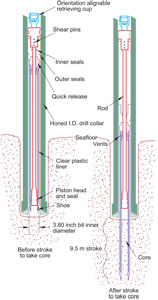

The advanced piston corer (APC), half-length APC (HLAPC), and extended core barrel (XCB) systems were used during Expedition 397 (Figures F2, F3). These tools and other drilling technology are documented in Graber et al. (2002).

The APC and HLAPC systems cut soft-sediment cores with minimal coring disturbance relative to other IODP coring systems. After the APC/HLAPC core barrel is lowered through the drill pipe and lands above the bit, the inside of the drill pipe is pressured up until one or two shear pins that hold the inner barrel attached to the outer barrel fail. The inner barrel then advances into the formation at high speed and cuts a core with a diameter of 66 mm (2.6 inches) (Figure F2). The driller can detect a successful cut, or full stroke, from the pressure gauge on the rig floor because the excess pressure accumulated prior to the stroke drops rapidly. The depth limit of the APC system, often referred to as APC refusal, is indicated in two ways: (1) the piston fails to achieve a complete stroke (as determined from the pump pressure and recovery reading) because the formation is too hard, or (2) excessive force (>60,000 lb) is required to pull the core barrel out of the formation. When a full stroke cannot be achieved, one or more additional attempts are typically made, and each time the bit is advanced by the length of the core recovered (note that for these cores, this results in a nominal recovery of ~100%). When a full or partial stroke is achieved but excessive force is insufficient to retrieve the core barrel, it can be drilled over, meaning that after the inner core barrel was successfully shot into the formation the drill bit is advanced to total depth to free the APC barrel.

The standard APC system uses a 9.6 m long core barrel, whereas the HLAPC system uses a 4.7 m long core barrel. The HLAPC typically is deployed after the standard APC has repeated partial strokes. During use of the HLAPC, the same criteria is applied in terms of refusal as for the APC system. Nonmagnetic core barrels were used for all APC and HLAPC coring. APC cores were oriented using the Icefield MI-5 core orientation tool when coring conditions allowed.

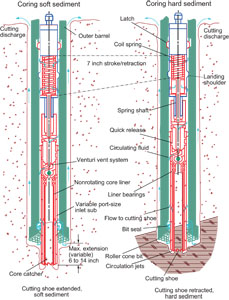

The XCB system is typically used when the APC/HLAPC system has difficulty penetrating the formation and/or damages the core liner or core. The XCB system can also be used to either initiate holes where the seafloor is not suitable for APC coring or interchanged with the APC/HLAPC when dictated by changing formation conditions. The XCB system is used to advance the hole when APC or HLAPC refusal occurs before the target depth is reached or when drilling conditions require it.

The XCB system has a small cutting shoe that extends below the large rotary APC/XCB bit (Figure F3). The smaller bit can cut a semi-indurated core with less torque and fluid circulation than the main bit, optimizing recovery. The XCB cutting shoe (bit) extends ~30.5 cm ahead of the main bit in soft sediment but retracts into the main bit when hard formations are encountered. It cuts cores with a nominal diameter of 5.87 cm (2.31 inches), slightly less than the 6.6 cm diameter of APC cores. XCB cores are often broken (torqued) into biscuits, which are disc-shaped pieces a few to several centimeters long with remolded sediment (including some drilling slurry) interlayering the discs in a horizontal direction and packing the space between the discs and the core liner in a vertical direction. This type of drilling disturbance may give the impression that the XCB cores have the same thickness (66 mm) as the APC cores.

The bottom-hole assembly (BHA) used for APC and XCB coring during Expedition 397 was composed of an 11⁷⁄₁₆ inch (~29.05 cm) polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) bit, a bit sub, a seal bore drill collar, a landing saver sub, a modified top sub, a modified head sub, 8¼ inch control length drill collars, a tapered drill collar, two stands of 5½ inch transition drill pipe, and a crossover sub to the drill pipe that extended to the surface.

During Expedition 397, the HLAPC was only used at Site U1586 because the cores retrieved with this system showed severe coring disturbance. Instead, we opted to use the XCB rotary system to advance the holes when the full APC system reached refusal because the XCB performed significantly better than expected with a PDC bit and cutting shoe; biscuiting was typically light to moderate, and the core quality was superior to that obtained with the HLAPC.

1.3. Drilling disturbance

Cores may be significantly disturbed by the drilling process and contain extraneous material because of the coring and core handling process. In formations with loose granular layers (sand, ash, foraminifer ooze, chert fragments, shell hash, etc.), granular material from intervals higher in the hole may settle and accumulate in the bottom of the hole because of drilling circulation and be sampled with the next core. The uppermost 10–50 cm of each core must therefore be examined critically for potential fall-in.

Common coring-induced deformation includes the concave-downward appearance of originally horizontal bedding. Piston action may result in fluidization (flow-in) at the bottom of, or sometimes in, APC cores. Retrieval of unconsolidated (APC) cores from depth to the surface typically results to some degree in elastic rebound, and gas that is in solution at depth may become free and drive core segments in the liner apart. When gas content is high, pressure must be relieved for safety reasons before the cores are cut into segments. Holes are drilled into the liner, which forces some sediment and gas out of the liner. As noted above, XCB coring typically results in biscuits mixed with drilling slurry. During Expedition 397, the main drilling disturbance observed was APC-induced flow-in and XCB coring–induced biscuiting. Severe gas expansion at Site U1588 prompted us to adopt a strategy of half advances of the XCB system and allowing the sediment to expand in the empty liner. We refer to this method as half XCB. Drilling disturbances are described in the Lithostratigraphy section of each site chapter and are indicated on graphic core summary reports, also referred to as visual core descriptions (VCDs).

1.4. Downhole measurements

1.4.1. Formation temperature

Formation temperature measurements were taken at specified intervals with the advanced piston corer temperature (APCT-3) tool (see Downhole measurements) embedded in the APC coring shoe. These measurements were used to obtain temperature gradients and heat flow estimates. During Expedition 397, formation temperature measurements were taken in Holes U1586A, U1587A, and U1588A. No temperature measurements were taken at Site U1385 because they were previously taken during Expedition 339. Information on downhole tool deployments is provided in the Operations, Physical properties, and Downhole measurements sections of each site chapter.

1.4.2. Wireline logging

During wireline logging operations, downhole logs are recorded with Schlumberger and IODP logging tools combined into tool strings, which are lowered into the hole after the completion of coring operations. Only the modified triple combination (triple combo) tool string was used during Expedition 397. It included the Hostile Environment Litho-Density Sonde (HLDS), Hostile Environment Natural Gamma Ray Sonde (HNGS), Enhanced Digital Telemetry Cartridge (EDTC), High-Resolution Laterolog Array (HRLA), Magnetic Susceptibility Sonde version B (MSS-B), and Dipole Sonic Imager (DSI). These tools measure gamma radiation, porosity, density, resistivity, magnetic susceptibility (MS), and P- and S-wave velocity. The tool string contains a telemetry cartridge for communicating through the wireline to the Schlumberger multitasking acquisition and imaging system (MAXIS) on the ship.

In preparation for logging, the boreholes were flushed of debris by circulating drilling fluid and were at least partially filled with seawater-based logging gel (sepiolite mud mixed with seawater) to help stabilize the borehole walls in sections where instability was expected from drilling and coring disturbance. The BHA was pulled up to ~80 m drilling depth below seafloor (DSF), where it protected the unstable upper part of the hole. The triple combo tool string was then lowered downhole on a seven-conductor wireline cable before being pulled up at a constant speed of 550 m/h to provide continuous log measurements of several properties simultaneously. Further details on the logging operations are described in the Downhole measurements sections of each site.

1.5. Core and section handling

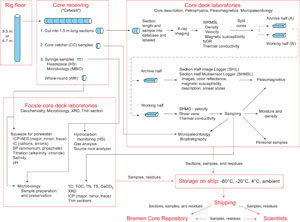

1.5.1. Whole-round cores

When a core barrel reached the rig floor, the core catcher from the bottom of the core was removed and taken to the core receiving platform (catwalk), and a sample was extracted for paleontological analysis. Next, the sediment core was extracted from the core barrel in its plastic liner. The liner was carried from the rig floor to the core processing area on the catwalk outside the core laboratory, where it was split into ~1.5 m sections. The exact section length was noted and entered into the database as created length using the Sample Master application. This number was used to calculate core recovery.

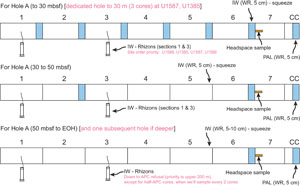

Once the core was cut into sections, whole-round samples were immediately taken for interstitial water (IW) chemical analyses from the bottom of selected core sections and headspace samples were taken from the top of a selected section (typically one per core) using a syringe for immediate gas analyses according to the IODP hydrocarbon safety monitoring protocol. When catwalk sampling was complete, liner caps (blue = top; colorless = bottom; yellow = bottom if a whole-round sample was removed from the section) were glued with acetone onto liner sections and sections were placed in core racks for analysis. IW samples also were taken with Rhizon samplers (Seeberg-Elverfeldt et al., 2005) from whole-round cores at selected sites (see Geochemistry for details on the Rhizon sampling program).

The curated length of the sediment cores was set equal to the created length and was updated very rarely (e.g., in cases of data entry errors or when section length kept expanding by more than ~2 cm). Depth in hole calculations are based on the curated section length (see Depth calculations).

The core sections then were placed in a core rack in the laboratory, core information was entered into the database, and the sections were labeled. All core sections were run through the Whole-Round Multisensor Logger (WRMSL) for MS and gamma ray attenuation (GRA) bulk density (see Physical properties). The core sections were also run through the Natural Gamma Radiation Logger (NGRL), and thermal conductivity measurements were taken once per core when the material was suitable.

1.5.2. Core section halves

After completion of whole-round section analyses, the sections were split lengthwise from bottom to top into working and archive halves. Cores were split with a wire or saw. Investigators should note that older material can be transported upward on the split face of a section during splitting. This was particularly true of pyritized burrows that can be dragged upward by the wire. The overall flow of cores, sections, analyses, and sampling implemented during Expedition 397 is shown in Figure F4.

Discrete samples were then taken from the working half of each core for moisture and density (MAD), paleomagnetic (PMAG), X-ray diffraction (XRD), carbonate (CARB), and inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) analyses. Samples were not collected when the core lithology was a high-priority interval for expedition or postcruise research, the core material was unsuitable, or the core was severely deformed. During the expedition, samples for personal postcruise research were taken where they concerned ephemeral properties (e.g., IW). We also took a limited number of personal or shared pilot samples (1) to determine if an analytical method works and yields interpretable results and how much sample is needed to guide postcruise sampling and (2) to generate low spatial resolution pilot data sets that can be incorporated in proposals and, potentially, increase their chances of being funded.

The archive half of each core was scanned on the Section Half Imaging Logger (SHIL) to provide line-scan images and then measured for point MS (MSP) and reflectance spectroscopy and colorimetry on the Section Half Multisensor Logger (SHMSL). Selected archive-half core sections were X-ray imaged. Labeled foam pieces were used to denote missing whole-round intervals in the SHIL images. The archive-half sections were then described visually and by means of smear slides for sedimentology. Finally, the magnetization of archive-half sections and working-half discrete pieces was measured with the cryogenic magnetometer and spinner magnetometer.

When all steps were completed, the cores were wrapped, sealed in plastic D-tubes, boxed, and transferred to cold storage space aboard the ship. At the end of the expedition, all working halves were shipped to the IODP Bremen Core Repository at the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (MARUM) (Germany). The archive halves of the cores were sent to various institutions for X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis: Site U1586 (Lisbon), Site U1385 (Cambridge), Site U1587 (Texas A&M), and Site U1588 (Bremen). Once core scanning XRF is completed, all cores will be returned to the IODP Bremen Core Repository for permanent storage.

1.6. Sample naming

1.6.1. Editorial practice

Sample naming in this volume follows standard IODP procedure. A full sample identifier consists of the following information: expedition, site, hole, core number, core type, section number, section half, and offset in centimeters measured from the top of the core section. For example, a sample identification of “397-U1586A-1H-2W, 10–12 cm,” represents a sample taken from the interval between 10 and 12 cm below the top of the working half of Section 2 of Core 1 (“H” designates that this core was taken using the APC system) of Hole U1586A during Expedition 397.

The drilling system used to obtain a core is designated in the sample identifiers as follows: H = APC, F = HLAPC, and X = XCB. Integers are used to denote the core type of drilled intervals (e.g., a drilled interval between Cores 2H and 4H would be denoted by Core 31).

When working with data downloaded from the LIMS database or physical samples that were labeled on the ship, three additional sample naming concepts may be encountered: text ID, label ID, and printed labels.

1.6.2. Text ID

Samples taken on JOIDES Resolution are uniquely identified for use by software applications using the text ID, which combines two elements:

- Sample type designation (e.g., SHLF for section half) and

- A unique sequential number for any sample and sample type added to the sample type code (e.g., SHLF30495837).

The text ID is not particularly helpful to most users but is critical for machine reading and troubleshooting.

1.6.3. Label ID

The label ID is used throughout the JOIDES Resolution workflows as a convenient, human-readable sample identity. However, a label ID is not necessarily unique. The label ID is made up of two parts: primary sample identifier and sample name.

1.6.3.1. Primary sample identifier

The primary sample identifier is very similar to the editorial sample name described above, with two notable exceptions:

- Section halves always carry the appropriate identifier (397-U1587B-20X-2A and 397-U1587B-20X-2W for archive and working half, respectively).

- Sample top and bottom offsets, relative to the parent section, are indicated as “35/37” rather than “35–37 cm.”

1.7. Depth calculations

Sample and measurement depth calculations were based on the methods described in IODP Depth Scales Terminology v.2 (https://www.iodp.org/policies-and-guidelines/142-iodp-depth-scalesterminology-april-2011/file) (Table T1). The definition of multiple depth scale types and their distinction in nomenclature should keep the user aware that a nominal depth value at two different depth scale types (and even two different depth scales of the same type) generally does not refer to exactly the same stratigraphic interval in a hole. The SI unit for all depth scales is meters (m).

Depths of cored intervals were measured from the drill floor based on the length of drill pipe deployed beneath the rig floor and referred to as drilling depth below rig floor (DRF), which is traditionally referred to as meters below rig floor (mbrf). The depth of each cored interval, measured on the DRF scale, can be referenced to the seafloor by subtracting the seafloor depth measurement (on the DRF scale) from the cored interval (on the DRF scale). This seafloor referenced depth of the cored interval is reported on the DSF scale, which is traditionally referred to as meters below seafloor (mbsf). In the case of APC coring, the seafloor depth was the length of pipe deployed minus the length of the mudline core recovered.

Depths of samples and measurements in each core were computed based on a set of rules that result in the core depth below seafloor, Method A (CSF-A), depth scale. The two fundamental rules for this scale are that (1) the top depth of a recovered core corresponds to the top depth of its cored interval (top DSF depth = top CSF-A depth) regardless of type of material recovered or drilling disturbance observed and (2) the recovered material is a contiguous stratigraphic representation even when core segments are separated by voids when recovered, the core is shorter than the cored interval, or it is unknown how much material is missing between core pieces. When voids were present in the core on the catwalk, they were closed by pushing core segments together whenever possible. The length of missing core should be considered a depth uncertainty when analyzing data associated with core material.

When core sections were given their curated lengths, they were also given a top and a bottom depth based on the core top depth and the section length. Depths of samples and measurements on the CSF-A scale were calculated by adding the offset of the sample (or measurement from the top of its section) to the top depth of the section.

Per IODP policy established after the introduction of the IODP Depth Scales Terminology v.2, sample and measurement depths on the CSF-A depth scale are commonly referred to with the custom unit mbsf, just like depths on the DSF scale. The reader should be aware, however, that the use of mbsf for different depth scales can cause confusion in specific cases because different mbsf depths may be assigned to the same stratigraphic interval. For example, a soft-sediment core from less than a few hundred meters below seafloor often expands upon recovery (typically by a few percent to as much as 15%), and the length of the recovered core exceeds that of the cored interval. Therefore, a stratigraphic interval in a particular hole may not have the same depth on the DSF and CSF-A scales. When recovery in a core exceeds 100%, the CSF-A depth of a sample taken from the bottom of the core will be deeper than that of a sample from the top of the subsequent core (i.e., some data associated with the two cores overlap on the CSF-A scale). To overcome the overlap problem, core intervals can be placed on the core depth below seafloor, Method B (CSF-B), depth scale. The CSF-B approach scales the recovered core length back into the interval cored, from >100% to exactly 100% recovery. If cores had <100% recovery to begin with, they are not scaled. When downloading data using the JOIDES Resolution Science Operator (JRSO) LIMS Reports (https://web.iodp.tamu.edu/LORE), depths for samples and measurements are by default presented on both the CSF-A and CSF-B scales. The CSF-B depth scale was particularly useful for Site U1588, which had severe gas expansion issues, prompting the use of the half XCB method to allow sediment to expand into empty liner.

Wireline logging data are collected at the wireline log depth below rig floor (WRF) scale, from which a seafloor measurement is subtracted to create the wireline log depth below seafloor (WSF) scale. For Expedition 397, the WSF depth scale was only used for preliminary data usage on the ship. Immediately after data collection was completed, the wireline logging data were transferred to the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Borehole Research Group (LDEO-BRG), where multiple passes and runs were depth matched using the natural gamma radiation (NGR) logs. The data were returned to the ship using the wireline log matched depth below seafloor (WMSF) scale, which is the final and official logging depth scale type for investigators.

During Expedition 397, all core depths below seafloor were initially calculated according to the CSF-A depth scale. Unless otherwise noted, all depths presented are core depths below seafloor calculated as CSF-A and reported in meters on the CSF-A scale. For Site U1588, depths are reported in meters on the CSF-B scale.

Core composite depth below seafloor (CCSF) depth scales are constructed for sites with two or more holes to create as continuous a stratigraphic record as possible. This also helps to mitigate the CSF-A core overlap problem and the coring gap problem. Using shipboard core logger–based physical properties data verified with core photos, core depths in adjacent holes at a site are vertically shifted to correlate between cores recovered in adjacent holes. This process produces the CCSF depth scale. The correlation process is achieved using the Correlator program (version 4.0 was used during Expedition 397) and results in affine tables that indicate the vertical shift of cores on the CCSF scale relative to the CSF-A scale or CSF-B scale in the case of Site U1588. Once the CCSF scale is constructed, a splice that best represents the stratigraphy of a site by utilizing and splicing the best portions of individual sections and cores from each hole is defined. Because of core expansion, the CCSF depths of stratigraphic intervals are typically 10%–15% deeper than their CSF-A depths. CCSF depth scale construction also reveals that coring gaps on the order of 1.0–1.5 m typically occur between two subsequent cores, despite the apparent >100% recovery. For more details on construction of the CCSF depth scale, see Stratigraphic correlation.

2. Lithostratigraphy

This section outlines the procedures for documenting the sedimentology of cores recovered during Expedition 397, including core description, sediment classification, smear slide preparation and description, and portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (pXRF) measurements. Only general procedures are outlined. All observations and data were uploaded directly into the IODP LIMS database using the GEODESC application. LIMS Information Viewer (LIVE) is a graphic display for core data (e.g., digital images of section halves, principal lithology, and drilling disturbance) that was used for quality control of the uploaded data sets.

2.1. Core preparation and digital color imaging

Prior to core description and high-resolution digital color imaging, the quality of the split surface of the archive half of each core was assessed and the surface was scraped lightly with a flexible metallic plate as needed. Cleaned core sections were then described in conjunction with images obtained using the SHIL, smear slide analysis, and measurements obtained using the SHMSL (see Physical properties).

The cleaned archive half was imaged with the SHIL as soon as possible to avoid sediment color changes caused by oxidation and drying. In cases of watery or soupy sediment, the surface was dried sufficiently to avoid light reflection prior to scanning. A high-resolution JPEG with a grayscale and depth ruler and a low-resolution cropped JPEG showing only the core section surface were created from the high-resolution TIFF files. These images were uploaded in LORE as Images > Core sections (LSIMG), and the RGB data were uploaded in LORE under Physical properties > RGB channels (RGB).

2.2. Smear slides

Smear slide microscopic analysis was used to determine biogenic and terrigenous components and abundance to aid in lithologic classification. For the first hole of each site, toothpick samples were taken at a frequency of at least two samples per core, or one sample per core in the case of HLAPC drilling. When sediments were highly disturbed, the number of smear slides per core was optionally reduced or nonexistent. For slide preparation, the sediment was mixed with distilled water, spread on a glass coverslip or glass slide, and dried on a hot plate at 120°C. The dried sample was then mounted with Norland optical adhesive Number 61 and fixed with ultraviolet light. Smear slides were examined with a transmitted-light petrographic microscope equipped with a standard eyepiece micrometer. Several fields of view (FOVs) were examined at some combination of 5×, 10×, 20×, and 40× along a transversal section to assess the abundance of detrital, biogenic, and authigenic components following standard petrographic techniques as stated in Rothwell (1989) and Marsaglia et al. (2013, 2015). The relative percent abundance of the sedimentary constituents was visually estimated using the techniques of Rothwell (1989). The texture of siliciclastic lithologies (e.g., relative abundance of sand-, silt-, and clay-sized grains) and the proportions and presence of biogenic and mineral components were recorded in the smear slide worksheet in GEODESC Data Capture. Components observed in smear slides were categorized as follows:

- TR = trace (≤1%).

- R = rare (>1%–10%).

- C = common (>10%–25%).

- A = abundant (>25%–50%).

- D = dominant (>50%).

Smear slides provide only a rough estimate of the relative abundance of sediment constituents. Occasionally, the lithologic name assigned on the basis of smear slide observation does not match the macroscopic designation because a small sample may not be representative of a much larger sediment interval. Additionally, very fine and coarse grains are difficult to observe in smear slides, and their relative proportions in the sediment can be altered during slide preparation. Therefore, intervals dominated by sand and larger sized components were examined by macroscopic comparison to grain size reference charts. Photomicrographs of all smear slides were taken and uploaded to the LIMS database.

2.3. Visual core description and standard graphic report

Macroscopic descriptions of each section (nominally 0–150 cm long) were input into GEODESC Data Capture. Two templates were constructed (drilling disturbance and macroscopic sediment), and columns were customized to include relevant descriptive information categories. For the macroscopic sediment template, these include lithology, sedimentary structures, diagenetic features, bioturbation intensity, deformational structures, and trace and macro fossils. A summary description was created for each core.

A simplified one page graphical representation of each core, or VCD (Figure F5), was generated using the LIMS2Excel application and a commercial program (Strater, Golden Software). VCDs are presented with the core depth below seafloor (CSF) depth scale, split-core photographs, graphic lithology, and columns for core disturbance, deformational structures, average grain size, sedimentary structures, diagenetic features, bioturbation, shipboard samples, age, MS, NGR counts, and color reflectance (L*a*b*). The graphic lithologies, sedimentary structures, and other visual observations are represented on the VCDs by graphic patterns and symbols (Figure F6). Each VCD also contains the summary description for the core. Only major lithologies are shown on the summary figure for each chapter.

2.4. Drilling disturbance

Drilling disturbances were described in a separate template in GEODESC Data Capture. The definitions of terms are paraphrased or taken from GEODESC and are consistent with the nomenclature of Jutzeler et al. (2014) and the methods described in Expedition 339 Scientists (2013) unless otherwise noted.

- Fall-in: debris in the top of a core that fell into the borehole from shallower depths during the coring process.

- Up-arching: soft-sediment layers in the plastic core liner bending down around the cut periphery due to friction when the core barrel is shot in sediment.

- Basal flow-in: flow structures and fabrics dominated by vertical banding in the lower portion of a piston core, which are interpreted to have flown or been sucked in by the piston action.

- Flow-in: identified based on vertical flow banding in the bottom of a piston core, caused by the suction action if the core fails to separate from the formation.

- Along-core gravel/sand contamination: gravel/sand is dragged or washed up or down between the in situ core material and the core liner.

- Gas expansion: may be indicated in piston cores (1) by voids several centimeters long that are observed in the core liner before the core is sectioned and curated, which are closed in processing and not accounted for in core recovery, or (2) when core recovery exceeds 110%, which is unlikely to be caused by elastic rebound and mechanical stretching alone.

- Soupy: intervals are water saturated and have lost all aspects of original bedding.

- Slurry: intervals are water saturated but maintain some aspects of original bedding.

- Mousse-like: very soft sediment, typically ooze, apparently remolded by the coring process through flowage with the core liner.

- Biscuiting: breakage of semilithified core into disc-shaped pieces, often separated by remolded mud that is a mixture of ground up sediment and drill fluid, resembling a macaroon biscuit.

- Crack: firm sediments that are broken but not displaced or rotated significantly.

- Brecciated: firm sediments that are pervasively broken and may be displaced or rotated.

- Void: an interval that has no core material, typically with a Styrofoam spacer with the word VOID marked on it.

- Disturbed bedding: sediments visibly mixed by the coring process.

- Fractured or fragmented: sediment displaying breakage.

- Core extension: a piston core that is extended or expanded to some degree by a combination of elastic rebound, gas expansion, and friction along the core liner.

- Punctured: displaying damage in the form of holes or slots.

- Mixed sediment: sediments are visibly mixed by the coring process.

- Sediment flowage: a collective term for structures resulting from the act of sediment flowing. Flowage is typically a result of piston coring action.

Drilling disturbances were also classified into four categories:

- Slightly disturbed (<1%),

- Moderately disturbed (1%–10%),

- Strongly disturbed (10%–50%), and

- Severely disturbed (50%–100%).

If a core or interval did not present any drilling disturbance type, a comment in the core summary was written to inform that drilling disturbance was absent and no description was entered into the GEODESC Data Capture spreadsheet.

2.5. Lithologic classification scheme

The principal lithologic name was assigned on the basis of the relative abundances of biogenic and terrigenous clastic grains and was noted in the microscopic and macroscopic sediment templates in GEODESC Data Capture. The Wentworth (1922) scale was used to define grain-size classes:

- The principal name of sediment with <50% biogenic grains was based on the dominant grain size of both the terrigenous and biogenic grains. This grain size was largely determined by analysis of smear slides.

- The principal name of sediment with ≥50% biogenic grains was classified as an ooze, modified by the most abundant specific biogenic grain type that forms 50% or more of the sediment. For example, if nannofossils exceed 50%, then the sediment was classified as nannofossil ooze. Biogenic constituents of similar composition were grouped together to exceed this 50% abundance threshold. For example, if nannofossils are 40% of the sediment and foraminifers are 20%, then the sediment was termed calcareous ooze or, in the case where the two components were clearly distinguishable, foraminifer-nannofossil ooze.

Major and minor modifiers were applied to any of the principal granular sediment names. Minor modifiers were those components with abundances >10% and <25% and were used in the lithology suffix followed by “with.” When more than one minor modifier is present, the component with the higher abundance is followed by the component with less abundance and so forth and linked with “and.” Major modifiers are those components with abundances >25% and <50% and were used in the lithology prefix. If the dominant component was siliciclastics, the modifier was based on the grain-size characteristics of both the terrigenous clastic and the biogenic grains. For example, if the sediments were dominantly (>50%) siliciclastic and contained (for all grains) 60% clay, 30% silt, and 10% sand, the lithology would be silty clay. If the component was biogenic, then the most specific biogenic grain type that exceeds the percentage threshold was used. The term “mud” or “muddy” was only used when clay and silt were mixed or could not be determined (i.e., not distinguishable without a smear slide).

Lower contacts between lithologies within sections were also described in the macroscopic sediment template in GEODESC Data Capture. Bioturbation, color, cut-and-fill, firmground, grain size, and sharp erosive contacts or boundaries were described. Contact shapes were described as curved, irregular, straight to irregular, straight, or wavy. Contacts were described as gradational, sharp to gradational, or sharp.

2.6. Stratification and sedimentary structures

The presence of sedimentary structures was noted in the macroscopic sediment template in GEODESC Data Capture. The definitions of terms were paraphrased from GEODESC:

- Lamination: a formation of lamina or laminae.

- Color banding: bands of different colors caused by layers of alternating textures or compositions, possibly emphasized by diagenetic alteration.

- Graded bedding: each layer displays a gradual and progressive change in particle size, usually from coarse at the base of the bed to fine at the top.

- Lens: a geologic deposit bounded by converging surfaces (at least one of which is curved), thick in the middle and thinning out toward the edges, resembling a convex lens.

- Patch: a section of sediment distinct from its surroundings, often due to lithology or color.

Stratification and sedimentary structures were characterized by the following thicknesses, similar to Stow (2005):

- Thin lamination (<0.3 cm),

- Thick lamination (0.3–1 cm),

- Very thin bed (1–3 cm),

- Thin bed (3–10 cm),

- Medium bed (10–30 cm),

- Thick bed (30–100 cm), and

- Very thick bed (>100 cm).

2.7. Deformational structures

The presence of deformational structures was noted in the macroscopic sediment template in GEODESC Data Capture. The definitions of terms were paraphrased from GEODESC:

- Churned or chaotic strata: soft-sediment deformation; irregular or unordered set of layers due to postdepositional processes.

- Contorted bedding: wavy, extremely disorganized, markedly and intricately crumpled, twisted, or folded beds that are overlain and underlain by parallel undisturbed layers.

- Contorted bedding: disorganized bedding that is not confined to a single uniform layer.

- Convolute lamination: wavy, extremely disorganized, markedly and intricately crumpled, twisted, or folded laminae that are confined within a single, relatively thin, well-defined, undeformed layer that die out both upward and downward and that are overlain and underlain by parallel undisturbed layers.

- Fault: a discrete surface or zone of discrete surfaces separating two sedimentary units across which one mass has slid past the other.

- Slump breccia: a contorted sedimentary bed produced by slumping and exhibiting brecciation (disaggregation in angular clasts).

- Slump fold: an intraformational fold produced by slumping (ductile movement) of soft sediments.

- Inclined deformed bedding: bedding that is inclined at an angle, rather than parallel.

- Homogenized interval: sediment that contains no clear structure or bedding or that appears mixed.

- Soft-sediment deformation: sediment that appears disturbed by ductile deformation and may exhibit a wavy structure or be otherwise deformed.

2.8. Bioturbation and trace fossils

Bioturbation was noted in the macroscopic sediment template in GEODESC Data Capture. Six levels of bioturbation are recognized using a scheme like that of Droser and Bottjer (1986). Bioturbation intensity is classified as follows:

- Complete (100%),

- Heavy (>60%),

- Moderate (40%–60%),

- Slight (10%–40%),

- Sparse (<10%), and

- Absent (none).

Trace fossil types were also identified where possible.

2.9. Other features

Diagenetic features, including nodules (of distinct or indistinct composition), pyrite, and dark patches were described. Macrofossil abundance was described as none, rare, few, common, or abundant (see Smear slides for quantification of these terms), and the type or species was identified when possible. Clast (>2 mm) counts and characteristics were described. These features were noted in the macroscopic sediment template in GEODESC Data Capture.

2.10. Spectrophotometry and colorimetry

The SHMSL employs multiple sensors for the measurement of bulk physical properties in a motorized and computer-controlled section-half logging machine. The sensors on the SHMSL include a spectrophotometer that measures reflectance spectroscopy and colorimetry, a point susceptibility meter that measures MS, and a laser surface analyzer. Spectrophotometry and MS were measured at 2 cm resolution for Sites U1586, U1587, and U1385 and Cores 397-U1588A-1H through 49X and 397-U1588B-1H through 9H. Measurements were taken at 4 cm resolution for Sections 397-U1588B-10X-1 through 10X-3 and 5 cm resolution for Sections 10X-4 through 64X-CC and Holes U1588C and U1588D. Reflectance spectroscopy (spectrophotometry) was carried out using an Ocean Insight QE-Pro spectrophotometer. This instrument measures the reflectance spectra of the split core from the ultraviolet to near-infrared range. Colorimetric information is extracted from the reflectance data to the L*a*b* color space system. The L*a*b* color space expresses color as a function of lightness (L*) and color values a* and b*, where a* reflects the balance between red (positive a*) and green (negative a*) and b* reflects the balance between yellow (positive b*) and blue (negative b*). When a* and b* are 0, there is no color and L* determines grayscale. On the SHMSL, MS was measured with a Bartington MS2 meter and MS2K contact probe (see Physical properties).

Accurate spectrophotometry using the SHMSL demands a direct and level contact between the instrument sensors and the split core surface. A built-in laser surface analyzer aids the recognition of irregularities in the split core surface (e.g., cracks and voids), and data from this tool were recorded to provide an independent check on the fidelity of SHMSL measurements.

2.11. Portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry

pXRF scanning was performed on selected sections to generate high-resolution element percentages and elemental ratios in bulk sediments. Individual measurements made with a Bruker Tracer 5 pXRF device take 135 s and consist of three measurement steps performed with beam energies of 30, 50, and 15 keV, each with 45 s of integration time. The spot size of the measurements was 8 mm.

The relative intensity of each element is calculated with the internal calibration GeoExploration using the Oxide3phase method. Reference materials (CS-M2 provided by Bruker, USGS BHVO-2, and USGS BCR-2) were measured before and after each measurement session to assure the quality of the data. During Expedition 397, pXRF measurements were conducted to investigate (1) sections with relatively high MS compared to surrounding sections and (2) intervals of cores in which the core catcher showed distinctive faunal assemblages.

2.12. Lithofacies classification

Lithofacies are qualitatively defined groups primarily based on lithology as well as all other criteria outlined above. The lithofacies characterized cover all sites, and therefore not all lithofacies are present at each site.

2.13. Lithostratigraphic units

Lithostratigraphic units are divided based on the frequency and occurrence of the lithofacies, additional information from smear slides, and other visual descriptions such as color and are generally corroborated with changes in physical properties data. Lithostratigraphic subunits are divided based on more subtle changes and where deformed intervals could be traced through the whole site.

3. Biostratigraphy

Preliminary shipboard biostratigraphic and paleoenvironmental information for Expedition 397 is provided by studying marine fossils. Paleontological studies are based on qualitative and semiquantitative analyses of calcareous nannofossils and foraminifer (planktonic and benthic) and ostracod assemblages. The studied microfossils are from mudline and core catcher samples from Hole A at each site. As needed, core samples from subsequent holes at a site were analyzed when the holes penetrated deeper strata than Hole A. At Site U1385, the first hole was designated Hole U1385F because Holes U1385A–U1385E were drilled previously during IODP Expedition 339. Similarly, only core catcher samples from Holes U1385F–U1385J were analyzed for biostratigraphy. To refine biostratigraphic boundaries, examine critical intervals, or study compositional variations in assemblages above and below significant changes in lithology, additional toothpick and/or cylinder samples were taken from split-core sections and analyzed as needed.

A taxonomic distribution table recording occurrences within each sample examined is presented along with the data for each group of microfossils. Relative abundance and preservation data were entered into the GEODESC application for all identified microfossil taxa and all paleontological data collected on board. In accordance with IODP policy, all data are available in the IODP LIMS database.

Shipboard biostratigraphic age assignments were based on analysis of the calcareous nannofossils and planktonic foraminifers using their biostratigraphic zonations and the ages of the highest occurrence (HO) and lowest occurrence (LO) of age-diagnostic species for all Sites (U1586, U1587, U1385, and U1588). Calcareous nannofossil and foraminifer age events from the middle Miocene to the Holocene were estimated by correlation to the geomagnetic polarity timescale (GPTS) of Lourens et al. (2004). The biozonation of Balestra et al. (2015) was used for calcareous nannofossil events for the late Pleistocene. Other zonations and calcareous nannofossil events used are summarized in Figure F7. Nannofossil and foraminifer bioevents are categorized by the following terminology:

- HO = highest occurrence.

- LO = lowest occurrence.

- CO = common occurrence.

- HcO = highest common occurrence.

- LcO = lowest common occurrence.

- HaO = highest abundant occurrence.

- LaO = lowest abundant occurrence.

- LrO = lowest regular occurrence.

- T = top.

- B = bottom.

- AB = acme bottom.

Figure F7. Correlation of GPTS, biostratigraphic zonation, and biohorizons used during Expedition 397.

The concept of acme (dominance interval) and paracme (absence interval) was also applied.

Details of the shipboard methods are described below for each microfossil group.

3.1. Calcareous nannofossils

Calcareous nannofossil bioevent ages were assigned based on the occurrence of calcareous nannofossils (relative abundance) in core catcher samples and in selected depths of all sections. Calibration of the identified events was derived mainly from Raffi et al. (2006). Additionally, Martini (1971) and Okada and Bukry (1980) standard zonal schemes were adopted.

The change in abundance of large Emiliania huxleyi (>4 µm), which characterizes Termination 1 in mid- to low-latitude water masses in the northeast Atlantic Ocean (Flores et al., 2010), was utilized.

Gephyrocapsa and Reticulofenestra species are grouped in several size categories (see Table T2). Specimens of Reticulofenestra that are <3 µm in size are referred to as “small Reticulofenestra;” specimens that are 3–5 µm in size are referred to as “medium Reticulofenestra.” Reticulofenestra specimens that are >6 µm in size are considered “large Reticulofenestra.”

Morphometric subdivision within Calcidiscus leptoporus s.l. and Coccolithus pelagicus s.l. complexes is used according to the taxonomy of Klejine (1993), Knappertsbusch et al. (1997), Steel (2001), Geisen et al. (2002), Quinn et al. (2003, 2004), and Parente et al. (2004).

Pliocene and Miocene events are mainly characterized by ceratolith and discoaster species, as well as variability in size of Reticulofenestra morphotypes (Raffi et al., 2006). Otherwise, taxonomic concepts for Neogene taxa were adopted from Perch-Nielsen (1985) and Young et al. (2022).

The Miocene/Pliocene boundary is a remarkable event in the Mediterranean Sea because it marks the Pliocene flooding after the Messinian Salinity Crisis, astronomically dated at 5.33 Ma (Hilgen, 1991), and the recovery of open marine deep-sea microfauna in the Mediterranean. However, its identification in the Atlantic Ocean is problematic because no major environmental change occurred in this area at this time. The location of this boundary is not well constrained because no bioevent has been identified within this time interval. Nevertheless, the biohorizons of the LO of Ceratolithus acutus and the HO of Discoaster quinqueramus, occurring at 5.34 and 5.54 Ma, respectively, may be used to approximate the boundary in the Atlantic.

The Pliocene/Pleistocene boundary has been formally established at 2.588 Ma at the boundary between the Piacenzian and Gelasian, located just above the Matuyama/Gauss magnetic reversal within Marine Isotope Stage 103 (Gibbard et al., 2010). The boundary can be approximated by the HO of Discoaster surculus (2.53 Ma) and the HO of Globorotalia puncticulata (2.41 Ma) (Figure F7).

3.2. Foraminifers

Foraminifer biostratigraphic events and their designations are derived mainly from Wade et al. (2011, 2018), BouDagher-Fadel (2015), King et al. (2020), and Gradstein et al. (2020) and references therein (Figure F7).

The taxonomic concepts of planktonic foraminifer species are based on Kennett and Srinivasan (1983), Hemleben et al. (1989), Spezzaferri et al. (2018), Schiebel and Hemleben (2017), and Poole and Wade (2019). Globigerinoides extremus is lumped into Globigerinoides obliquus because of the difficulty of distinguishing the two species in sediments from Atlantic regions. We also decided to use Neogloboquadrina pachyderma (dextral) instead of Neogloboquadrina incompta.

Benthic foraminifers provide limited control of biostratigraphic age. Only “Stilostomella extinction” can potentially be used. This extinction is marked by the disappearance from the world ocean of a large number of species of deep-sea foraminifers of Stilostomellidae, Pleurostomellidae, and Nodosariidae. A pulsed decline of these foraminifer groups would have started at ~1.2 Ma, and the final extinction of Stilostomella would have occurred between 0.7 and 0.58 Ma (e.g., Hayward, 2002; Kawagata et al., 2005). Generic-level taxonomic assignments of benthic foraminifer species are based on Loeblich and Tappan (1988) with updates from Hayward (2002).

3.3. Ostracoda

Ostracods provided no biostratigraphic control but were examined and recorded at every site for paleobathymetric an paleoenvironmental purposes. Taxonomic assignments follow Breman (1978), Colalongo and Pasini (1980), Faranda et al. (2008), Alvarez Zarikian (2009), and Yasuhara and Okahashi (2014, 2015).

3.4. Sample preparation methods

3.4.1. Calcareous nannofossils

Calcareous nannofossil samples were prepared following the standard smear slide technique with Norland optical adhesive. Calcareous nannofossils were examined with a Zeiss polarized microscope at 1000× magnification.

Preservation includes effects of dissolution and overgrowth. Preservation of calcareous nannofossils was categorized as follows:

- G = good (little or no evidence of dissolution and/or overgrowth; specimens are identifiable to the species level).

- M = moderate (minor to moderate dissolution and/or overgrowth; most specimens are identifiable to the species level).

- P = poor (extreme dissolution and overgrowth; some specimens are identifiable to the species level).

Total abundance of calcareous nannofossils was categorized as follows:

- VA = very abundant (>100 specimens per FOV).

- A = abundant (11–100 specimens per FOV).

- C = common (1–10 specimens per FOV).

- F = few (1 specimen per 2–10 FOVs).

- R = rare (1 specimen per ≥11 FOVs).

- B = barren.

Abundances of individual taxa or groups of calcareous nannofossils were categorized as follows:

- D = dominant (>20 specimens per FOV).

- A = abundant (11–20 specimens per FOV).

- C = common (1–10 specimens per FOV).

- F = few (1 specimen per 2–10 FOVs).

- R = rare (1 specimen per ≥11 FOVs).

- P = present (abundance not quantitatively determined).

3.4.2. Foraminifers

For counting planktonic and benthic foraminifers, 20–30 cm3 of sediment from each core catcher was analyzed. Unlithified sediment samples were soaked in tap water and washed through a 63 µm sieve. In addition, mudline samples were taken from most of the holes and used for ecological study. These samples were collected by emptying the sediment/water material from the top casing of the core from each hole into a bucket. Rose bengal was used to detect living foraminifers.

The washed samples were dried at 60°C. Dry residues larger than 63 µm were sieved again over a 150 µm screen. Samples were split into subsamples to obtain at least 300 specimens of planktonic foraminifers. The entire sample was examined when it contained fewer planktonic foraminifer specimens.

The samples were analyzed under Zeiss Discovery V8 and Zeiss Stemi SV11 stereomicroscopes. To avoid contamination between successive samples, the sieves used for wet sieving were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath for several minutes, and those used for dry sieving were cleaned with compressed air.

Planktonic and benthic foraminifer abundance in the >150 µm fraction in relation to the total residue of each sample was categorized as follows:

- D = dominant (>30%).

- A = abundant (>10%–30%).

- F = few (>5%–10%).

- R = rare (1%–5%).

- P = present (<1%).

- B = barren.

Relative abundance of individual taxa or groups of foraminifers was characterized as follows:

- D = dominant (>30%).

- A = abundant (>10%–30%).

- F = few (>5%–10%).

- R = rare (1%–5%).

- P = present (<1%).

The state of preservation is defined including the effects of diagenesis, epigenesis, abrasion, encrustation, and/or dissolution. The preservation of planktonic and benthic foraminifers was classified as follows:

- VG = very good (no evidence of breakage or dissolution).

- G = good (only very minor dissolution and no recrystallization; <10% of specimens broken).

- M = moderate (frequent etching and partial breakage; 30%–90% of specimens unbroken).

- P = poor (much dissolution and recrystallization; broken specimens dominate).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is used to confirm and document the potential dissolution of some specimens.

3.4.3. Ostracoda

Ostracods were picked, counted, and identified only in the >250 µm sediment grain size fraction of all samples analyzed for foraminifers using a Zeiss Discovery V8 stereomicroscope. Ostracod abundance was defined by the number of valves (carapaces were counted as 2 valves) per sample as follows:

- A = abundant (>50 valves).

- C = common (≥20–50 valves).

- F = few (5–20 valves).

- R = rare (<5 valves).

- B = barren (no specimens in the entire sample).

Ostracod preservation was defined as follows:

- VG = very good (valves translucent; no evidence of overgrowth, dissolution, or abrasion).

- G = good (valves semitranslucent; slight evidence of overgrowth, dissolution, or abrasion).

- M = moderate (common but minor calcite overgrowth, dissolution, or abrasion).

- P = poor (substantial overgrowth, dissolution, or fragmentation of the valves).

3.5. Paleoenvironment

All examined microfossil groups allow characterization of paleoenvironmental conditions such as changes in water masses, water depth, and seawater temperature and to identify intervals of varying marine productivity (e.g., Colmenero-Hidalgo et al., 2004; Baumann et al., 2005; Narciso et al., 2006; Kucera, 2007; Salgueiro et al., 2010; Ruiz et al., 2008; Alvarez Zarikian et al., 2009). Changes in abundance and preservation of assemblages are related to hydrographic parameters such as salinity, temperature, and oxygen saturation conditions. Variations in benthic foraminifer assemblages are very useful as proxies for deepwater circulation, food availability, oxygen content, water depth, and other physicochemical properties (e.g., Murray, 2006; Jorissen et al., 2007). In particular, their variations along the Iberian continental margin may have been controlled by the interplay between surface productivity and changes in the relative proportions of deepwater masses prevailing in the area (i.e., North Atlantic Deep Water, Antarctic Bottom Water, or Mediterranean Outflow Water) (e.g., Schönfeld and Zahn, 2000).

4. Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetic studies during Expedition 397 focused on measuring the natural remanent magnetization (NRM) of archive-half sections before and after alternating field (AF) demagnetization using the shipboard 2G Enterprises Model 760R-4K superconducting rock magnetometer (SRM). We used AF with peak fields up to 20 mT to remove drilling-induced overprint and identify the direction of characteristic remanent magnetization (ChRM). The acquired paleomagnetic directional data (excluding those from disturbed/void intervals and section ends) were matched to a GPTS (Ogg, 2020) to construct magnetostratigraphy for the cored sediment sequences.

We collected discrete cube samples from working-half sections, typically two to four samples per core in selected holes from Sites U1586 and U1587 and about one sample per core in selected holes from Sites U1385 and U1588. NRM of discrete samples was measured before and after stepwise AF demagnetization with peak fields up to 50 or 80 mT using either the SRM with in-line AF demagnetizer or the AGICO JR-6A spinner magnetometer with a D-Tech Model D-2000 AF demagnetizer. The detailed and more complete NRM demagnetization data of the cube samples were used to help verify and improve the archive-half data-based magnetostratigraphy.

4.1. Instrumentation tests

Prior to coring operations, we conducted tests to check the spatial resolution and response function of the SRM and compare background noise levels and measurements made on the SRM and the JR-6A spinner magnetometer. Our tests included (1) calibrating the JR-6A spinner magnetometer and using it to repeatedly measure the calibration sample and a random selection of 10 empty plastic cubes used for discrete sampling (i.e., 7 cm3 Natsuhara-Giken sampling cubes), (2) repeatedly measuring the continuous sample tray as an archive-half sample using the SRM, (3) repeatedly measuring the discrete sample tray with empty cubes as working-half cube samples using the SRM, and (4) repeatedly measuring the JR-6A calibration sample on the SRM over a 50 cm interval at every 0.2 cm resolution while it is oriented parallel/antiparallel to each of the three SRM measurement axes.

The JR-6A calibration sample from AGICO is a magnetized thin wire embedded in the center of an 8 cm3 transparent cube. It contains a dipole-like remanence (intensity = 7.99 A/m) pointing toward the center of one of the cube surfaces. We calibrated the JR-6A using the calibration sample and then repeatedly measured the calibration sample five times. This was followed by measurement of 10 randomly selected empty cubes (the type we used for discrete sampling). The repeated measurements of the calibration sample yielded a mean intensity of 8.01 A/m with standard deviation of 1.17 × 10−2 A/m. The empty cube measurements yielded a mean intensity of 1.99 × 10−5 A/m with standard deviation of 1.85 × 10−5 A/m, suggesting the practical noise level of sample measurements on the JR-6A is probably on the 10−5 A/m level or above (e.g., due to inaccuracy in positioning the samples in the holder).

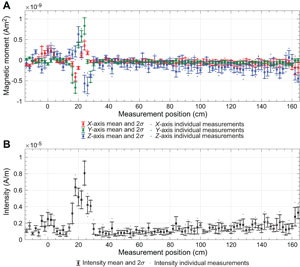

For the SRM continuous tray measurement test, we cleaned the tray using glass cleaner, AF demagnetized the tray with 80 mT peak field, and conducted a background measurement. We then measured the empty continuous tray as a 1.5 m long archive-half sample five times. Measurements were made at 2 cm intervals and used a leader and trailer length of 14 cm (same as that used for most core section measurements during the expedition). Drift- and background-corrected magnetic moment along the three axes is within ±1 × 10−9 Am2 and mostly varies around ±0.3 × 10−9 Am2 (Figure F8). The Z-axis measurement appears to be noisier than those of the X- and Y-axis. Using a standard section-half cross area of 17.5 cm2 and effective lengths of 7.30, 7.30, and 9.00 cm along the X-, Y-, and Z-axis measurements, the intensity of the repeated empty tray measurements (after drift and background correction) is mostly <0.4 × 10−5 A/m and reaches up to ~1 × 10−5 A/m. The practical SRM measurement noise level is therefore on the 10−5 A/m level for section-half measurements.

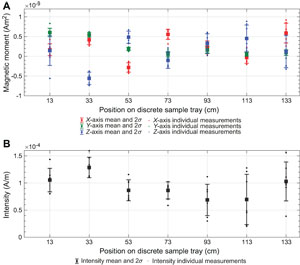

Prior to the SRM discrete tray measurement test, we cleaned and AF demagnetized the discrete tray (with 80 mT peak field) and conducted a background measurement. We then placed empty cubes at the seven measurement positions on the discrete tray (i.e., at 13, 33, 53, 73, 93, 113, and 133 cm) and repeatedly measured each of the seven empty cubes 10 times. In total, 3 out of the 10 repeated measurements experienced flux jumps on the Z-axis (~4 × 10−8 Am2 level) and were not used for further analysis. Drift- and background-corrected magnetic moment of the remaining measurements is within ±1 × 10−9 Am2 (Figure F9A), similar to those of the continuous tray test. The intensity of the repeated discrete tray with empty cubes measurement is mostly <1.5 × 10−4 A/m (Figure F9B), which should be the approximate noise level for cube measurement on the SRM.

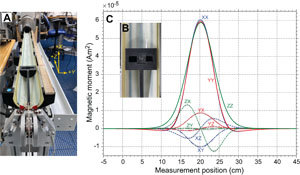

To facilitate measurement of the JR-6A calibration sample on the SRM, we 3-D printed a holder (see Figure F10A, F10B) to position the calibration sample so that its center is 20 cm away from the SRM measurement start line and 2.1 cm above the bottom of the tray (i.e., center of mass on the cross-section of a half-round core with 7.2 cm diameter). The 3-D printed holder allows accurate orientation of the remanence signal parallel/antiparallel to each of the three SRM measurement axes. We measured the calibration sample as a 40 cm long archive-half section with leader and trailer length of 5 cm (total = 50 cm) at every 0.2 cm resolution. We repeatedly measured the sample while orienting its remanence signal toward/opposite to the +X-, +Y-, and +Z-directions (total = six orientations) of the archive-half measurement coordinates of the SRM (Figure F10A). For each of the six orientations, we collected measurements four times after rotating the sample in 90° steps using that orientation as the rotation axis. We flipped data measured while the sample was oriented toward the −X-, −Y-, and −Z-directions and plotted all 24 runs of data as gray dots in Figure F10C. As a result, each of the nine terms of the SRM sensor response (i.e., XX, XY, XZ, YX, YY, YZ, ZX, ZY, and ZZ, where AB means B-axis response while remanence signal is oriented toward A-axis; A, B = X, Y, or Z) has eight runs of data. These data fall close to one another, and we use the mean of these data (colored curves in Figure F10C) as an estimate of the SRM sensor response function.

The peaks of XX, YY, and ZZ response terms occur at 20.2 cm, suggesting the SRM track positions are fairly accurate. Peak magnetic moment of XX, YY, and ZZ terms are 6.04 × 10−5, 5.94 × 10−5, and 5.88 × 10−5 Am2, which are about 5.5%, 7.0%, and 8.0% smaller than the expected values of 6.39 × 10−5 Am2 (i.e., 7.99 A/m × 8 × 10−6 m3), respectively. Full widths at half maximum for XX, YY, and ZZ terms are 7.23, 7.25, and 8.17 cm, respectively. Cross-term responses appear to be significant (Figure F10C). The effective lengths for XX, XY, XZ, YX, YY, YZ, ZX, ZY, and ZZ terms are 7.09, −1.15, 0.03, 1.05, 7.15, −0.01, 0.09, 0.01, and 8.90 cm, respectively. More accurate estimates of the SRM sensor response will require the integration of repeated measurements of a magnetic point source while placing it at different positions on the cross-section of a half-round core (see Xuan and Oda, 2019).

4.2. Core collection and orientation

Cores were collected using nonmagnetic core barrels for the APC and HLAPC systems. Nonmagnetic core barrels are more brittle than standard core barrels and are not used with the XCB system (see JOIDES Resolution standard coring systems). The BHA included a monel (nonmagnetic) drill collar. This collar is required when the Icefield MI-5 core orientation tool is used. During Expedition 397, this collar was used for all APC, HLAPC, and XCB cores (even when the Icefield MI-5 was not used) because it can potentially reduce the magnetic field in the core barrel and near where the core is cut.

The Icefield MI-5 can only be used with APC core barrels. It uses three orthogonally mounted fluxgate magnetometers to record the orientation of the multiple toolface (MTF) with respect to magnetic north. The MTF is aligned with the double lines scribed on the core liner. The tool declination, inclination, total magnetic field, and temperature are recorded internally at regular intervals until the tool’s memory capacity is filled. For a measurement interval of 10 s, which was used during Expedition 397, the tool can typically be run for ~24 h, although we aimed to switch tools every ~12 h. Prior to firing the APC, the core barrel is held stationary (along with the pipe and BHA) for several minutes. During this time, data are recorded to constrain the core orientation. When the APC fires, the core barrel is assumed to maintain the same orientation, although the core barrel can rotate and/or the core liner can twist as it penetrates the sediment. The orientation correction that converts the observed declination (Dobs) to a true declination (Dtrue) is given by the following formula:

where MTF is the magnetic tool face angle from the Icefield MI-5 and Damb is the ambient geomagnetic field declination at the drill sites.

The 2020 International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF) declination values for Sites U1385, U1586, U1587, and U1588 are −1.78°, −1.97°, −1.86°, and −1.59°, respectively. We report orientation angle estimated from the Icefield MI-5 (MTF) for all oriented cores of each site as a table in the site chapters.

4.3. Archive-half measurements

NRM measurement of the archive-half sections using the SRM was controlled by the shipboard Integrated Measurement System (IMS) software (version 13). We cleaned the SRM sample tray with glass cleaner at the beginning of every working shift (every ~12 h), at the start of new holes, or as deemed necessary. The sample tray was then AF demagnetized and measured using the section background routine to maintain accurate tray correction values that were applied to each measured core section. We used AF with an 80 mT peak field to demagnetize the tray at the beginning of Expedition 397. A software and hardware communication issue caused the SRM in-line degauss coils to overheat. Tests conducted after the coils cooled down suggested the coils were performing normally, but the maximum peak field for AF demagnetization was limited to 50 mT to avoid potential damage to the SRM in-line degauss coils. We used AF with a 40 mT peak field to demagnetize the SRM sample tray afterward. For all section-half measurements, track speed was set to 10 cm/s, data acquisition was set for no averaging, and 1 Hz data filtering with 1000 ms settling time was used.

For archive halves from most of the holes recovered during Expedition 397 (i.e., all holes at Sites U1586 and U1587 and Holes U1385F, U1385G, and U1588A), SRM measurements were made at 2 cm resolution along the core section and for a 14 cm leader interval and a 14 cm trailer interval. Measurements from the leader and trailer intervals immediately before and after the sample serve the dual function of monitoring the background magnetic moment and allowing for future deconvolution analysis. We typically measured the NRM of archive halves before and after AF demagnetization with a peak field of 20 mT. Some sections were measured using more detailed (3–5) demagnetization steps (e.g., 0, [5], 10, [15], and 20 mT [steps in brackets are not always carried out]) to check if a lower demagnetization level would be sufficient to remove the drilling-induced overprint. Measurement of a 1.5 m long core section at 2 cm resolution (with 14 cm leader and trailer intervals) before and after 20 mT demagnetization takes ~9 min and 20 s. The core flow (the analysis of one core after the other) through the laboratory dictates the available time for measurements. When core flow increased, we either prioritized and only measured NRM after the 20 mT demagnetization step at 2 cm resolution (e.g., for some cores from the low sedimentation rate sites) or we measured NRM before and after 20 mT demagnetization at 4 cm resolution (e.g., for some cores from the higher sedimentation rate sites). For a 1.5 m core section, it takes ~6 min to measure NRM at 2 cm resolution (with 14 cm leader and trailer intervals) after only 20 mT demagnetization and ~6 min and 40 s to measure NRM at 4 cm resolution (with 12 cm leader and trailer intervals) before and after 20 mT demagnetization.

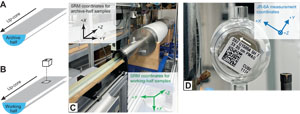

SRM data are reported relative to IODP orientation conventions: +X-orientation points into the face of the working half (toward the double line or away from the single line), +Y-orientation points toward the left (right) side of the working (archive) half when looking downcore, and +Z-orientation is downcore (see Figure F11A, F11B). The shipboard IMS software registers the orientation of the archive- and working-half samples and automatically converts the SRM measurement coordinates accordingly (see Figure F11C). SRM data were stored using the standard IODP file format and automatically uploaded to the LIMS database.

4.4. Discrete cube samples and measurements

During Expedition 397, we collected oriented discrete cube samples from working-half sections from selected holes at each site for detailed and more complete AF demagnetization experiments to help verify and improve the archive-half data-based magnetostratigraphy. We typically collected two to four cube samples per core from selected holes at Sites U1586 and U1587 and one cube sample per core from selected holes at Sites U1385 and U1588. Samples were taken using plastic Natsuhara-Giken sampling cubes, which have a 2 cm external edge length and an internal volume of ~7 cm3. Cube samples were taken from the center of working halves and away from disturbed sediments near the core liner. We avoided sampling sections and intervals that were visually disturbed. For biscuited XCB cores (see Lithostratigraphy), cube samples were taken from the centers of biscuits. For the top few cores from the selected holes where sediments are soft, we pushed the cubes directly into the section with the arrow marker on the cube pointing toward the stratigraphic up direction. We collected most cube samples by pushing a hollow metal tube into the working-half section and then extruding the sample onto a clean flat surface before we fit the sample into the cube. This ensures cube samples collected using either method (i.e., directly pushed into the section or extruded from the hollow metal tube) have consistent orientation.

Depending on the core flow and availability of the SRM, we used either the SRM with in-line AF demagnetizer or the JR-6A spinner magnetometer with a D-Tech Model D-2000 AF demagnetizer for NRM measurement of the cubes before and after stepwise AF demagnetization with peak fields up to 50 or 80 mT. For measurement using the JR-6A spinner magnetometer, NRM of cube samples was measured after stepwise demagnetization with peak fields of 0, (5), (8), 10, (15), 20, (25), 30, (35), 40, (45), 50, 60, (70), and 80 mT. Demagnetization was carried out manually in three axes using a D-Tech Model D-2000 AF demagnetizer. Demagnetization steps in parentheses were not always included for all samples depending on sample demagnetization behavior and/or time available. For measurement on the JR-6A spinner magnetometer, cubes were positioned in the sample holder so that the surface with the arrow marker faced the user and the arrow marker pointed toward the top left (Figure F11D). Measurements on the JR-6A were controlled by AGICO Remasoft (version 6.0) using the following settings for all cube measurements:

JR-6A data were manually uploaded to the LIMS database.

The majority of cube samples were measured on the SRM after stepwise AF demagnetization with peak fields of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, (12) 15, (18), 20, (22), 25, (28), 30, (32), 35, (38), 40, (42), 45, (48), 50, (55), (60), (70), and (80) mT (steps in parentheses were not always included). The cube samples were placed on the SRM discrete sample tray so that the surface with the arrow mark (also the surface of working-half sections) was on top and the arrow mark pointed away from the SRM (Figure F11B, F11C). The NRM of some cube samples (i.e., those from Holes U1586A and U1586B) was measured on the SRM with demagnetization up to 80 mT, and the rest of the cube samples measurements on the SRM only used demagnetization up to 50 mT. Measurements on the SRM appear to be frequently compromised by flux jumps along the Z-axis just before sample measurements start (potentially because of antenna effect when the sample tray was moving into the SRM sensor area). The jumped values occur on all seven cube samples measured in the same batch and are usually ~4 × 10−8 Am2 (possibly due to the jump of one flux count on the SRM Z-axis that is equivalent to 3.8825 × 10−8 Am2). These flux jumps can significantly affect the measurement of samples that carry weak magnetization. We removed SRM measurements compromised by flux jumps from further analyses. For samples measured with demagnetization up to 50 mT, we used a demagnetization sequence with 22 steps to ensure enough measurement data remained after removing those influenced by flux jumps (two to six steps of data often need to be removed).

4.5. Data filtering and magnetostratigraphy